Introduction

On 11 February 2015, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan paid a visit to Cuba as part of a three-leg Latin American tour. This was the second visit of a high-level Turkish delegation to Latin American countries, the first being in 1995. Erdoğan’s trip drew the attention of international media and scholars to the special features of Turkey’s relations with Latin America and the Caribbean.

Turkey’s political, economic and cultural influence in regional and global affairs has been gradually increasing in the last few years, following a multi-directional or multi-regional vocation. In the last decade, Turkey’s growing relevance in different regions has gone beyond that of a trade partner. Under the AK Party, Turkey has launched a so called paradigm shift in its foreign policy, which former Prime Minister and former Minister of Foreign Affairs Prof. Ahmet Davutoğlu1 underlines as a ‘Multi-Dimensional Foreign Policy Approach.’ Following Davutoğlu’s guidelines, Turkey has formed new routes in international policy and enhanced those new routes with humanitarian and development aid, making use of both the cultural element and the religious dimension. As part of this larger initiative, policies aimed at strengthening Turkey’s strategic ties were directed toward Latin America and the Caribbean region, including Cuba. Thanks to this new approach and to Turkey’s economic growth, Ankara is now acknowledged as a development partner that provides humanitarian aid and developmental assistance, mainly through the gradual involvement of the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA). In light of these trends, Turkey’s soft power in the region is growing.

Drawing on the conceptualization of soft power given by Joseph Nye Jr., this article studies two linked elements of Turkish soft power: agents and behavior. Turkey’s soft power has gained importance, thanks to the gradual involvement of new state and non-state actors (agents) along with the adoption of novel frameworks, such as cultural diplomacy, public diplomacy and humanitarian diplomacy (behavior). The current research has the purpose of analyzing Turkey’s approach toward Latin America and the Caribbean region through the prism of soft power theory, and through a specific case study, i.e. Turkey-Cuba relations. The working assumption is that Turkey has been able to increase its presence and influence in the region, thanks to a particular soft power-oriented approach known as multi-dimensional policy, which reflects both new behavior and new agents. An analysis of Turkey-Cuba relations will not only help improve the literature about Turkey’s foreign policy on a subject which has not yet been adequately examined, but will also underline features and peculiarities of Turkey’s soft power, such as the emerging “Mosque Diplomacy.”2

Theoretical and Conceptual Background of Soft Power

Power is one of the most central and yet problematic concepts in political science and international relations (IR), where it has a variety of forms and features. In the most general sense, power may refer to any kind of influence exercised by objects, individuals, or groups upon each other.3 One of the most influential definitions of power remains that of Max Weber, who defines power as the “probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests.”4 In other words, power is a ‘zero-sum’ game: either you win or you lose. According to the literature, the best way to materialize national interests is to use military and economic power elements with a view to forcing other actors to undertake a cost-benefit calculation. In summary, most actors pursue a ‘carrot and stick’ policy in their foreign policies.5 However, in a post-modernist and globalized society, ‘soft’ power, which is based on a ‘value-based’ notion of power, becomes increasingly important relative to ‘hard’ power, which is dependent upon military and economic resources.

This essay assumes the definition of power asserted by Joseph Nye Jr., who argues that power is “the ability to influence the behavior of others to get a desired outcomes one wants.”6 During the last two decades, Nye’s concept of soft power has become widely known in IR literature and elsewhere; it is now a term used by scholars, policymakers, and others, albeit in many different ways. The origin of the concept is deeply related to an analysis of US power and foreign policy during the 1980s, when declinist theories and interpretations of the international order dominated mainstream IR debates.7 The concept of “soft power,” which Nye coined in his 1990 book, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, was strengthened by his Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (2004), and further elaborated in his The Powers To Lead (2008); it is rooted in the idea that alternative power structures exist in international relations alongside economic and military power. Soft power is neither an evolution or involution nor a substitute for hard power, it is simply another form of power.

The values that Turkey represents, as well as its historic and cultural depth, have mobilized regional dynamics and provided opportunities for the creation of new spheres of influence

According to Nye, “the distinction between hard and soft power is one of degree, both in the nature of the behavior and in the tangibility of the resource.”8 Unlike hard power, soft power explains fields of influence and attraction beyond military and economic indicators, and refers to a country’s social human capital. This is why soft power may differ from country to country. Soft power is an autonomous form of power, which has its own rules, features and characteristics, and “does not depend on hard power.”9 For Nye, soft power is better seen as a strategy a country may use in order to gain its objectives without coercion or payments, but with attraction founded on culture, political values, and legitimate and moral foreign policy. As such, soft power helps to shape international institutions and policy agenda. To Nye, soft power explains the “attractiveness of a country’s culture, political notions and policies,” the power of attraction, as opposed to the power derived from military force and economic sanctions. In sum, soft power rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others, without the use of force, coercion or violence. That is, the ability to co-opt people rather than coerce them.

As we have seen, co-optive or soft power rest on the resources, behavior and agents that comprise a country’s attractiveness. Resources are tangible or intangible capabilities, goods, and instruments at disposal; behavior is the action itself, the manner or way of acting, and the conduct of an agent. In terms of resources, soft power resources are the assets that produce attraction; co-optive power can be seen in the attraction exerted by an agent through a certain behavior. According to Nye, the soft power of a country rests on three resources: its culture (in places where it is attractive to others), its political values (when it lives up to them at home and abroad), and its foreign policies (when they are seen as legitimate and having moral authority). This is because “in international politics, the resources that produce soft power arise in large part from the values an organization or country expresses in its culture, in the examples it sets by its internal practices and policies, and in the way it handles relations with others.”10 Culture, education, arts, media, film, literature, higher education (universities, research centers, think tanks, etc.), non-governmental organizations, tourism, platforms for economic cooperation and diplomacy, are all soft resources that may be used to produce and to feed soft power.11

Turkey has adopted a multifaceted foreign policy, and a series of new, assertive behaviors, moving towards a more independent role in international affairs. This shift epitomizes a general reorientation of Turkey’s foreign policy, no longer gravitating firmly around the Western axis

Another important feature of Joseph Nye’s theory, which is also useful in terms of understanding Turkey’s foreign policy agenda, has to do with the agents or actors that really hold soft power. The definition of hard and soft power given by Nye does not differentiate between agents. For many years, international affairs have been understood in state-centric terms, and only recent studies consider non-state actors in terms of contributions and challenges to a government’s decision-making process.12 Even though Nye is commonly known as one of the fathers of interdependence theory,13 in his work there is a lack of attention given to non-state actors or agents. However, on the basis of this theory, we can argue that institutions, large corporations, civil society organizations and movements, and even individuals hold soft power.

Behaviors and Agents of Turkey’s Soft Power

Turkey’s soft power is different from that of other countries in both its form and content. In other words, it has distinctive features in terms of both resources and agents, both of which mark an original approach. The values that Turkey represents, as well as its historic and cultural depth, have mobilized regional dynamics and provided opportunities for the creation of new spheres of influence.14 Some elements and features of Turkish soft power are similar to those of other non-Western rising powers such as Brazil and South Africa.15 Similarly to these countries, Turkey’s foreign policy has mainly followed strategies that deploy non-material aspects of power: consensus-building initiatives, diplomacy and persuasion. Considering its history, recourse to soft power seems to make sense in view of Turkey’s interests, goals and resources.16

Prior to the rise of the AK Party, Turkey’s foreign policy tradition, for the most part, stayed within the parameters of the Kemalist foreign policy approach, which can be summed up as a security oriented, status quo focused, and strategic alignment. After their electoral victory in 2002, the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AK Party/AKP) began cautiously revitalizing Turkey’s role in the international sphere. From then on, Turkey has realized that the acquisition of global status results in a paradigm shift, and that the ability to strengthen ties with different regions by means of a multi-track diplomacy brings together political, economic and cultural elements. Therefore, Turkey has adopted a multifaceted foreign policy, and a series of new, assertive behaviors, moving towards a more independent role in international affairs. This shift epitomizes a general reorientation of Turkey’s foreign policy, no longer gravitating firmly around the Western axis, as had been the case in the past. Although a Western orientation is still a strong element of Turkish foreign policy, it will likely continue in a more flexible and dynamic form.17

During the past few years, Turkey’s shift of axis has been the subject of many studies and academic debates. According to some of the literature on the topic, which can be categorized as globalist, Turkish foreign policy is drifting away from the West as it develops its relations with other regions, in order to build its position as an effective global power. According to this argument, Turkey’s activism towards different continents and inside various international fora are components of this new, grand strategy, traced to former Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu’s vision, who described Turkey as a “central country with multiple regional identities that cannot be reduced to one unified character.”18 Davutoğlu’s geostrategic vision is a mix of realist elements, referable to the traditional Kemalist security-centered foreign policy, and a strong liberal character focused on elements such as soft power, conflict resolution, developmental aid and humanitarianism.19

Among the agents of Turkish soft power, a special place is held by the official Turkish aid agency, the Cooperation and Development Agency of Turkey (TIKA)

According to Davutoğlu, Turkey no longer thinks of itself as a bridge country, but has gained self-confidence in its role and position as a central country or power. The central state metaphor is not novel in Turkish foreign policy discourse;20 it represents a pillar of a wider theory known as central country theory. Davutoğlu believes that Turkey’s unique geographic and geo-cultural position gives it a special, central-country (merkez ülke) role, and therefore Turkey cannot define itself in a defensive manner. Turkey is identified both geographically and historically with more than one region and one culture, enabling the country to have a central role and maneuver in several regions simultaneously.21 Following the Arab uprising (2011) and the wave of political instability that hit the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the Ankara government increased the prospect for a more liberal functionalist foreign policy, based on the promotion of stability, economic cooperation, democratization and interdependence.22

Two key paradigms of the central country theory are relevant here: multi-directional and multi-dimensional or multi-track approaches, and both have modified Turkish behaviors.

• The multi-directional approach is defined by Turkey’s ability to project its influence and its interests in different directions, thus departing from its previous unidirectional –Westward oriented– approach. Now Turkey is open to all regions around the Turkish center and beyond.23

• The multi-dimensionality or multi-track policy can be assessed in a qualitative manner, highlighting that alongside Turkey’s growing presence in the major supranational organizations, in the last decade, there has been a gradual shift of the tools used with a general transnationalization of its own relations.24 As a result, there has been an increase of Turkey’s civilian capacity through the involvement of non-state actors in the policy-making process, and the use of new, soft power tools in public diplomacy.25

The process of Turkey’s reorientation as a central country was accelerated by the diversification of roles through the involvement of a greater number of new agents, alongside the implementation of another principle of Davutoğlu’s strategy: total performance. This principle means including in the foreign policy agenda civil society organizations like NGOs (non-governmental organizations), business circles, think-tanks, public intellectual figures, and transnational social movements, thus mobilizing their support.26 All of these institutions can provide input into the foreign policy-making process, in contrast to a past where there was no room for such agents.27 This principle is linked with the concept of multi-dimensionality, which indicates the ability to operate on different levels and on different fronts; from ‘official’ diplomatic relations, within international and regional organizations, to transnational relations or society to society, developed by non-state agents.28

Among the agents of Turkish soft power, a special place is held by the official Turkish aid agency, the Cooperation and Development Agency of Turkey (TIKA). TIKA was initially established to help the economic transition of states in Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Balkans. However, after 2003, TIKA transformed into a more global aid agency, expanding its areas of operation.29 TIKA is one of the state’s executive tools; as such, it supports development projects to serve such long-term purposes as the development of social and economic infrastructure and, to a lesser extent, the provision of humanitarian support when needed in times of crisis. The most notable expansion of TIKA’s activities has taken place in Africa and Latin America. Nowadays, with the momentum of two offices in Latin America (Mexico and Columbia), it is clear that TIKA is playing a pivotal role in Turkey’s opening toward the region, thanks to several activities and assistance projects in the fields of agricultural, health and education.

The Historical Legacy of Turkey-Cuba Relations

The historical events of the Ottoman Empire and later of the Turkish Republic reveal a series of intertwining with Latin America and the Caribbean region, although not always expressed by direct contact. There is a small but increasing literature about the diplomatic and commercial contacts between the Ottoman Empire and Latin America.30 Indeed, according to several modern scholars of the ‘decline paradigm,’ the fate of the Ottoman dynasty was partly determined by Latin America and the Caribbean.31 European discoveries and the new navigation techniques of the 15th and 16th centuries widened the existing geographical boundaries, allowing Europeans to cross oceans and circumnavigate Africa. Within a century (1492-1600), the axis of world trade had shifted and the Ottoman Empire ceased to be the center of business affairs. Before the 17th century, all commodities, from textiles and spices to precious metals, were obliged to cross the Ottoman domains, but from the second half of the 1600s, trade routes ceased to pass through Ottoman ports and markets.

From the 19th century onward, after the period of reforms known as Tanzimat (1839-1871), the Porte became an active participant in the European state system, known as the European concert. Even though the Porte’s involvement lasted only from 1856 to 1878, it was useful in widening the Ottoman outlook in an increasingly ‘globalized’ world. Some Ottoman Jewish merchants paved the way and created an opportunity for the first direct contact with Latin America. Toward the end of the century, trade routes slowly emerged linking Turkey with North and Latin America and the Caribbean islands, including Cuba. As a consequence, thousands of people migrated from the Ottoman Empire to the region for trade reasons. During the same period Cuba emerged as an immigrant society. Between 1860 and 1870, some immigrants departed from Ottoman territory and arrived in what has been portrayed as an effort either to introduce ‘Arab colonos’ or to smuggle blacks “under fake nationality.”32 In 1887, Havana’s population stood at only 250,000; two decades later it had grown to 300,000, swollen by the arrival of a large number of Spanish immigrants and, to a lesser extent, a population of Ottoman peoples, as a result of a greater emigration from the Ottoman Empire.33 Among the latter there were Muslims (mainly Arabs),34 Sephardic Jews (from Anatolia and Morocco), Christians (Orthodox, Maronites, Chaldeans), and Armenians.

A meeting between the then Speaker of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey Ali Şahin and President of Costa Rika Oscar Arias on November 25, 2009. | AA PHOTO / HAKAN GÖKTEPE

A meeting between the then Speaker of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey Ali Şahin and President of Costa Rika Oscar Arias on November 25, 2009. | AA PHOTO / HAKAN GÖKTEPE

In Cuba, the Ottoman immigrants were called ‘Los Turcos’ regardless of ethnicity or religion, as they all had Ottoman passports.35 The Turco category was an imposed label, rather than a self-constructed one, and was not always accepted by all Ottoman immigrants.36 Their influx into Cuba’s culture and economy was significant. In particular, the Sephardic community contributed to the expansion of Cuba’s sugar industry. The general convulsion in Europe and the rapid dissolution of the Ottoman domains had repercussions on transatlantic migration during the first decades of the 20th century. Even after the birth of the Turkish Republic (1923), many Turkish citizens (Muslims37 and Jews38) were among the streams of migrants that arrived on the island. Although many of them settled in Cuba, others used the island as a stepping-stone to enter the United States or various South American countries.39

Among the factors which transformed Turkey’s strategy from regional coercive power to a benign or soft power, were the economic interests of a new entrepreneurial class

As Ignacio Klich and Jeffrey Lesser argue, ‘Turco’ migrants, both Muslim and Jews, were central to Cuba’s process of economic development as well as that of other regional states (Argentina, Chile, Brazil and Colombian Caribbean).40 Like other migrant groups, they developed associations which reflected their background and social and political concerns; these included political organizations (e.g. La Sociedad Siria), magazines (Cercano Oriente), newspapers (Al-Sayf), and cultural services (Al-Ethead), which served their fellow immigrants.41

Although Turkey’s relations with the region had roots from the Ottoman Empire years, Latin America and the Caribbean region had been the Mountain of Qaf42 in Turkey’s cultural imagination for decades, due to geographical restrictions. In addition to the geographic realities, social and political unrest during Turkey’s transition from a world empire (Ottoman) to a republic state (Turkish), also weakened Turkey’s few relations with the region. After the birth of modern Turkey (1923), relations still maintained a low profile in which mutual contacts were constrained to a couple of friendship and trade agreements.12 During the early years of the Republic of Turkey, the number of resident Turkish diplomatic missions to Latin America increased, including those to Cuba. Diplomatic relations between the Republic of Turkey and Cuba formally started in 1952; the first Turkish embassy was founded there in 1979 and the first ambassador to Cuba, Mr. Nazmi Akıman, assumed his position in 1980.43

With the outbreak of the Cold War, Turkey, a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) since 1952, pursued a Western-oriented foreign policy, becoming an outpost of the democratic Western bloc. NATO was the determinant of Turkey’s foreign policy, generating an internationally ‘securitized’ agenda that gave precedence to defense and security over economic development and political democratization.44 During these years, Cuba witnessed the rise to power of Fidel Castro after six years of armed guerrilla warfare (the Cuban Revolution) against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship (1952-1959). Castro’s regime broke relations with the United States, tightening trade agreements with the Soviet Union; in 1961, Cuba became part of the Communist bloc. Within a few years, Turkey and Cuba resided in opposite camps, but in similar positions. Both countries represent, geographically, the farthest point of their own blocks, thus the main deterrent on the enemy’s doorstep. The stories of Turkey and Cuba intertwined without any direct touching.

During the Cold War, there were no bilateral relations between Turkey and Cuba; however, the Muslim community residing on the island enjoyed tolerance and had good relations with the Cuban government. Over the decades, a romantic understanding of Cuba arose in the Turkish public imagination, mainly from the positive models of Che Guevara and the peculiar form of socialism adopted by Fidel Castro.

After 1991, Turkey presented itself as a relatively autonomous ally of NATO, and both countries have adopted a positive attitude towards their bilateral relations. For instance, on 2 August 1991 a bilateral agreement for visa exemption between Turkey and Cuba was signed.45 According to the agreement, both Turkish and Cubans who hold diplomatic, special/official or service passports can visit each other’s countries without needing an official visa, and can stay in one another’s countries for up to 90 days. In 1993, an “Air Transport Agreement” was signed between Turkey and Cuba. According to this agreement, both parties will have direct flights, traffic rights, input and output permit laws and regulations, immunity from customs and other taxes and fees with the normal aviation equipment storage of consumer goods, direct transit traffic, financial provisions, the provisions of capacity, representation, and aviation security. This agreement came into effect on 18 April, 1996.46 Apart from these examples, undoubtedly a significant turning point occurred in 1996 when Fidel Castro participated in the United Nations Habitat Meeting held in Istanbul, which was very important in the grounds of high level visits.

Turkey’s Foreign Policy toward Cuba: From Coolness to Opening

Turkey’s international aid programs and development projects indicate a widening of Ankara’s geographic vision toward regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean.47 Prior to the mid-1990s, geographical and cultural distances posed too high a barrier for bonding.48 This type of low profile relationship prior to the 1990s, known as a consent to resignation, was due to Turkey’s dominant western state identity during that period.49 However, in the 2000s, Turkey witnessed a turning point with the adoption of new set of behaviors, and the integration of new state and non-state agents in its soft power.

Among the factors which transformed Turkey’s strategy from regional coercive power to a benign or soft power, were the economic interests of a new entrepreneurial class. This new business elite drove the Turkish agenda toward a trading stateparadigm,50 which challenged traditional Turkish partners in the economy and aimed at diversifying trade alternatives in line with changes in the global political economy power configuration. Making Latin America more attractive to Turkey were the high economic performances of several countries (Chile, Brazil, and Mexico), which joined the emerging economies league. Therefore, the region gained significant importance for Turkey, and this importance is indicated by an opening in Turkey’s foreign policy.51 That new opening marks not only a foreign policy break from the previously predominant axis, but also a search for opportunities in the region for further cooperation on different levels.52

After the Cold War, both countries adopted a positive attitude towards their bilateral relations and there are no existing problems regarding relations between Turkey and Cuba

With the AK Party victory in 2002, Turkey’s big opening towards the globe was initiated; thanks to this, new opportunities have been sought and new cooperation has been instituted with many states. Turkey reformulated its foreign policy destinations in accordance with the new ruling party’s foreign policy doctrine. According to this new doctrinal approach in Turkish Foreign Policy, Turkey gave momentum to its new destinations, through development and humanitarian aid at first, and then through enhanced bilateral and multilateral political and economic cooperation with those destinations. Among those new destinations,53 without doubt, Latin America and the Caribbean hold a significant importance.

An important turning point in Turkey’s relations with Latin America and the Caribbean came in 2006, a year declared “Latin America Year” in Turkey, marked by an official action plan towards the region. In addition to those events, several factors indicate that Turkey’s relations with Latin America and the Caribbean have improved significantly. Those factors can be summed up as: increased frequency of mutual official visits, increased mutual diplomatic representatives, and an increased number of mutual inter-parliamentary friendship groups in Turkey’s Grand National Assembly (TBMM).54

As Levaggi underlines, between 2009 and 2011, the number of high-level visits and contacts increased between Turkey and Latin America and the Caribbean countries.55 These include: President Erdoğan’s visit to Mexico in December 2009,56 and Brazil and Chile in May 2010;57 Argentinean President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s visit to Turkey in January 2011;58 President of Brazil (2003-2011), Lula da Silva’s visit to Turkey in 2009;59 and Dilma Rousse, current president of Brazil’s visit to Turkey in October 2011.60 The President of Costa Rica, Oscar Arias, also visited Turkey in November 2009,61 and the President of Colombia, Juan Manuel Santos, visited Turkey in November 2011.62

Turkey's opening to Latin America: TİKA provided 80 uniforms for firemen in Paraguay. | TİKA / AA PHOTO

Turkey's opening to Latin America: TİKA provided 80 uniforms for firemen in Paraguay. | TİKA / AA PHOTO

With the momentum of this series of high-level visits, Turkey’s gradual opening toward the region reached its peak with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s visit to Cuba on 11 February 2015. This visit marks an historic step that has carried Turkish-Cuban relations on to a new phase: from coolness to opening. This “opening” stage arose from three main dimensions: the establishment of political, economic and cultural ties.63

The Political Dimension

Political relations between Turkey and Cuba remained null for some time, due to the nature of the Cold War era. Nevertheless, even though being members of opposite blocks, there was always good faith in the countries’ relations. After the Cold War, both countries adopted a positive attitude towards their bilateral relations and there are no existing problems regarding relations between Turkey and Cuba. For instance, Cuba’s official position on the false allegations of the 1915 events, the PKK terror and the Cyprus issue has always been positive towards Turkey. The former President of Cuba, Mr. Fidel Castro participated in the UN Habitat meeting in Istanbul in 1996.64

Turkey's opening to Latin America: TİKA restored the clock tower known as the "Ottoman Clock" in Mexico City in 2010. | TİKA / AA PHOTO

Turkey's opening to Latin America: TİKA restored the clock tower known as the "Ottoman Clock" in Mexico City in 2010. | TİKA / AA PHOTO

With that said, Cuba has made some criticism of Turkey’s Syria policy; however, those criticisms stand against the backdrop of a general understanding, and Turkey and Cuba have enjoyed a growing cooperation on international platforms. Similarly, Turkey’s approach to matters related to Cuba has always rested on a similar basis of good faith. These good relations support Turkey and Cuba’s multilateral relations as well. For example, in the UN, Cuba supported Turkey’s bid to be a member of the Security Council. Cuba was the first country to support Turkey’s candidacy for Expo 2015 in Izmir. Besides, the two countries support each other and work together on many subjects, including international conflict resolution and the fight against terrorism.65

Against that backdrop, President Erdoğan’s official visit to Cuba enhanced expectations for boosting bilateral relations. President Erdoğan mentioned during his visit that the U.S. sanctions on Cuba were not right. He told the reporters that “We do not find sanctions over Cuba right in either a humane and conscientious sense.”66 President Erdoğan’s official position on this matter implies cooperation between Turkey and Cuba on the international level and crowns the political dimension of the relations. The Cuban Ambassador to Turkey, Alberto Gonzales Casals, anticipated that Erdoğan’s visit to Cuba would have a positive impact on relations between the two countries. He also added that, “We have historical expectations from this visit, which is the first in our bilateral relations.”67

The Economic Dimension

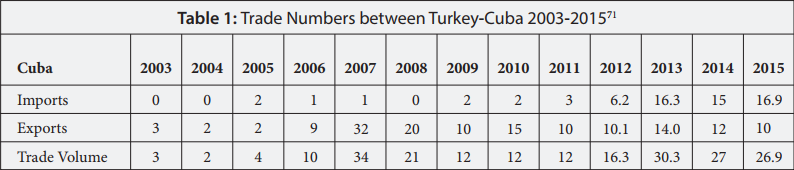

While developments at the political and institutional level are important, Turkey’s opening to Cuba is quantifiably measurable in bilateral trade. According to the numbers, Turkey’s most imported items from Cuba are tobacco products, medicine and charcoal, while Turkey’s most exported items to Cuba are iron and steel products, rubber and soap.68 The last Joint Economic Commission Meeting between Turkey and Cuba was held in Cuba on 28-31 October 2009.69 Since that time, it has remained unclear what Turkey and Cuba’s next step will be to increase mutual trade volume. Of course this stalemate is mostly caused by Cuba’s closed regime, centrist economic order, and state-controlled banking system. During his 2015 visit, President Erdoğan said that the low level of Cuba-Turkey trade volume stems mainly from the various sanctions on the country, of which Turkey disapproves.70

Despite the chronic obstacles to trade with Cuba, on 28 June 2014, the Cuban Investment Law came into force as a lure mechanism for foreign investors.72 This recent legislation on foreign investors protocol may lure foreign investors to Cuba; indubitably investors from Turkey will also be attracted.73 In addition to this new protocol, during President Erdoğan’s visit a business forum was arranged which was also vital for enhancing economic relations between the two countries.74 This recent event also marks the crowning of the economic dimension of relations between Turkey and Cuba.

The Cultural Dimension

The third dimension of President Erdoğan’s visit is surely the deepening of cultural ties between Turkey and Cuba. The enhancement of bilateral tourism capacity is, without doubt, a major step for both countries, but tourism is not the only area of cultural relations between Turkey and Cuba. Language, history and religious matters are the other elements of the relation. Here are a few examples:

• The Turkish History and Cultural Center Foundation was established according to the cooperation of TIKA, Havana University and the Turkish Havana Embassy in 2010. It was signed by all parties in 2011. Since 2013, an academician from Ankara University has given regular lectures on Turkish language and Turkish History at the center.75 In addition, a periodical journal called Cuadernos Turquinos has been published through the center, in order to introduce Turkish culture to Cubans.76

• The Aşk-ı Nebi (Love of the Prophet) exhibition, organized by Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, TIKA, the Turkish Religious Foundation, the Cuban Islam Association, and the Islam Culture and Arts Platform, which displays calligraphic works by renowned calligraphy and ornamentation artists, made its Latin American debut during President Erdoğan’s visit to Cuba.77 Abdülkadir Özkan, Secretary-General of the Islam Culture and Arts Platform, said that the relationship between Cuba and Turkey, which started in the 18th century, should focus on cultural development. “We believe that the culture and arts protocol that our Minister of Culture and Tourism signed with his Cuban counterpart is an important step for the relationship between the two countries.”78

Mosque Diplomacy

In November 2014, during the 1st Latin American Countries Muslim Leaders Summit, President Erdoğan mentioned in his speech that Islam came to Latin America in the 12th century;79 in his memoirs, Columbus recalls seeing a mosque at the top of a hill on the shores of Cuba, and, if official approval is granted, a mosque will be constructed in Cuba for the Muslim society.80 President Erdoğan mentioned this intention again during his official visit to Cuba. Although Cuban officials had already agreed with Saudi Arabia upon the construction of a mosque in Havana, President Erdoğan told President Raul Castro that Turkey would like to build a mosque in the capital, which would be the first place of worship for the island’s 3,500 Muslims.81President Erdoğan also stated, “We want to build the mosque ourselves. We don’t want a partner. If you find it appropriate, we would like to build it in Havana. But if you have promised a Havana mosque to other people, then we can build our Ortaköy Mosque in another Cuban province.”82 President Erdoğan also mentioned that Turkey will continue moving forward with this vision through The Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı, DİB) and the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA).83

In extending “Mosque Diplomacy” towards Cuba, Turkey aims to unlock the region through the use of soft power

This initiative, and others like it, have earned the colloquial title, “Mosque Diplomacy.” For example, the restoration of mosques carried out by the DİB and TİKA have constituted solid ground for Turkey’s public diplomacy in the Balkans.84 As a recent instance of this approach, the Ferhat Paşa/Ferhadija Mosque was re-opened in Bosnia-Herzegovina earlier this year thanks to Turkey’s efforts. In 1993, during the Bosnian war, the 16th century mosque, under UNESCO protection as an outstanding example of Ottoman architecture, was blown up, and a parking lot was later built where the mosque had stood. Turkey contributed to the cost of rebuilding, and after 15 years of extensive restoration work, carried out by TİKA, the mosque was reopened on 7 May 2016, the anniversary of its destruction.85 In extending “Mosque Diplomacy” towards Cuba, Turkey aims to unlock the region through the use of soft power.

Subsequent to these cultural events, many criticisms arose both from abroad and within Turkey as well. Some criticized President Erdoğan’s intention to construct a mosque in Cuba as being rooted in a historical fallacy;86 some approached this intention with skepticism,87 and some considered it a power play between Saudi Arabia and Turkey.88 However, regardless of these criticisms, it should be very clear that constructing a mosque in Cuba would be an extension of Turkey’s soft power in the region. As Beril Dedeoğlu says, building mosques abroad fulfills several functions for Ankara at once: “On the one hand, the help offered by Turkey prevents more radical groups from extending help to Muslims there and at the same time, the mosque-building program serves ‘as an instrument’ of soft power to widen Turkey’s influence.”89 Similarly, Mehmet Özkan emphasizes the importance of Turkey’s religious opening toward the region as follows: “With the DİB’s new opening, religion is not only becoming one of the most important elements of Turkey’s soft power in Latin America but also an important aspect of Turkey’s social connection with different regions.”90 In this manner, the crowning of the cultural dimension of relations between Turkey and Cuba mostly relies on Turkey’s soft power overtures toward to Cuba.

Turkey’s “Mosque Diplomacy” is emblematic of its soft power, and is a key example of Turkey’s foreign policy towards the region: developing relations through foreign aid, through culture, and most of all, through new behaviors and agents of Turkey’s soft power

Conclusion

Turkey was pushed into a uni-dimensional foreign policy for more than 70 years, due to the pressures surrounding the Cold War era. However, when the AK Party emerged with a new vision, Turkey took note of the profound changes occurring on the global scale, and began to follow a foreign policy that prioritized diversifying its economic partners and political allies. Today, thanks to central country theory and the multi-dimensional foreign policy conceptualized by the former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, Turkey has many different vectors around the globe.91 Among these, Latin America and the Caribbean region have significance, because they constitute a vital and strategic area for Turkey where extensive economic opportunities exist to extend its current international profile.92

Relations between Turkey and Cuba have been crowned in the new era in three main dimensions; political, economic and cultural. As mentioned before, relations between Turkey and Cuba have deep roots, but had rested dormant in a deep sleep for seventy years (1923-1990). Now, they have totally awoken and stand likely to remain so. Turkey’s “Mosque Diplomacy” is emblematic of its soft power, and is a key example of Turkey’s foreign policy towards the region: developing relations through foreign aid, through culture, and most of all, through new behaviors and agents of Turkey’s soft power.

Endnotes

- This study takes into account Davutoğlu’s foreign policy doctrine, and evaluates its relevance to current Turkish foreign policy-making, as well as its limitations. Without conflating Davutoğlu’s academic theory with his actions as an advisor and Foreign Minister, there are few doubts that the new course of Turkey’s foreign policy has been strong influenced by his ideas.

- For the concept of ‘soft power’ and its meaning for Turkey, see the special issue on soft power of Insight Turkey, Vol. 10, No. 2 (April–June 2008).

- Robert Dahl, “Power,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 12 (New York: Collier-Macmillan, 1968).

- Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization (Glencoe: The Free Press, 1967), trans. by A. M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons.

- Tarık Oğuzlu, “Soft Power in Turkish Foreign Policy,” Australian Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 61, No. 1 (2007).

- Joseph Nye Jr, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004), pp. 4-5; Joseph Nye Jr., The Powers to Lead (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Inderjeet Parmar and Michael Cox (ed.), Soft Power and US Foreign Policy: Theoretical, Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (London/New York: Routledge, 2010).

- Joseph Nye Jr., Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 1990), p. 267; Nye Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, p. 7; Joseph Nye Jr., “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 616 (2008).

- Nye Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, p. 9.

- Nye Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, p. 8.

- Philip Seib (ed.), Toward a New Public Diplomacy (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009).

- States and their officials are no longer the only actors in diplomatic relations. After the end of the Cold War, the public dimension of diplomacy has gained increasing importance. A dynamic of this development has been fostered by globalization; it is destined to become even more pronounced in the coming years. See Richard C. Snyder, Burton Sapin, Valerie Hudson and H. W. Bruck, Foreign Policy Decision-Making, Revisited (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

- Interdependence in the social sciences describes a situation of mutual dependence between social actors. Interdependence in IR can be due to two factors: state interdependence and societal interdependence. Many studies since the 1970s attempt to use the concept of ‘interdependence’ to rebut the realist thesis. See Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse and Beth A. Simmons (ed.), Handbook of International Relations (Los Angeles/London: SAGE, 2013), pp. 401-425. About Nye’s position, see Joseph Nye Jr and John D. Donahue (ed.), Governance in a Globalizing World (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2000).

- For the concept of soft power in international literature and its meaning for Turkey, see the special soft power issue of Insight Turkey, Vol. 10, No. 2 (April-June 2008).

- Malte Brosig (ed.), The Responsibility to Protect – From Evasive to Reluctant Action? (Johannesburg and Tshwane: Hanns Seidel Foundation, 2012); Olusola Ogunnubia, Ufo Okeke-Uzodikea, “South Africa’s Foreign Policy and the Strategy of Soft Power,” South African Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2015).

- Michael Kai, “Brazil’s Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding Policies in Africa,” Journal of International Peacekeeping, Vol. 17 (2013).

- Ziya Öniş and Şuhnaz Yılmaz, “Between Europeanization and Euro-Asianism: Foreign Policy Activism in Turkey during the AKP Era,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (2009).

- Ahmet Davutoğlu, “Turkey’s New Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2007,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 10, No. 1 (2008), p. 78.

- Davutoğlu had, in his academic work, called for Turkey to move from its traditional threat assessment approach to an active engagement in regional political systems. See Şaban Kardaş, “From Zero Problems to Leading the Change: Making Sense of Transformation in Turkey’s Regional Policy,” TEPAV-

ILPI Turkey Policy Brief Series, Vol. 5, No. 1 (2012). - Pınar Bilgin, “Only Strong States Can Survive in Turkey’s Geography’: The Uses of ‘Geopolitical Truths’ in Turkey,” Political Geography, Vol. 26, No. 7 (2007).

- Ahmet Sözen, “A Paradigm Shift in Turkish Foreign Policy: Transition and Challenges,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1 (2010).

- Hakan Fidan, “A Work in Progress: The New Turkish Foreign Policy,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2013), pp. 91-92; Bülent Aras, “Davutoğlu Era in Turkish Foreign Policy Revisited,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4 (2014), p. 409.

- Davutoğlu stated that Turkey should act as a central country and break away from its static and single-parameter policy. See Nicholas Danforth, “Ideology and Pragmatism in Turkish Foreign Policy: From Ataturk to the AKP,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 3 (2008); Joerg Baudner, “The Evolution of Turkey’s Foreign Policy under the AK Party Government,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 16, No. 3 (2014).

- Birgül Demirtaş, “Turkey and the Balkans: Overcoming Prejudices, Building Bridges and Constructing a Common Future,” Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 18, No. 2 (2013); Kemal Kirişci, “Turkey’s Engagement with Its Neighborhood: A “Synthetic” and Multidimensional Look at Turkey’s Foreign Policy Transformation,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2012).

- Senem B. Çevik and Philip Seib, Turkey’s Public Diplomacy (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015).

- Ahmet Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik. Türkiye’nin Uluslararası Konumu (İstanbul: Küre, 2001), p. 81.

- Bülent Aras, “The Davutoğlu Era in Turkish Foreign Policy,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 11, No. 3 (2009), p. 139.

- During the Fourth UN Conference on the Least Developed Countries held in Istanbul in 2011, Davutoğlu stressed the importance of civil society organizations as a valuable tool for bringing global peace and stability. He stressed that they are an integral part of international relations and that Turkey believes strong civil society can grow only through heavy state support, saying “this is why we [the AK Party government] strongly support civil society organizations participating in international affairs.” “Davutoğlu Says Civil Society Key in Development of LDCs,” Sunday Zaman, May 8, 2011, retrieved March 23, 2015 from http://www.todayszaman.com/news-243200-Davutoğlu-says-civil-society-key-in-development-of-ldcs.html.

- Hakan Fidan and Rahman Nurdun, “Turkey’s Role in the Global Development Assistance: The Case of TIKA (Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency),” Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans, Vol. 10, No. 1 (2008).

- Mehmet Temel, XIX. ve XX. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Latin Amerika İlişkileri (Istanbul : Nehir Yayınları, 2004); Monique Sochaczewski Goldfeld, O Brasil, o Império Otomano e a Sociedade Internacional: Contrastes e Conexões (1850-1919) (Rio de Janeiro: Tese Dotourado, 2012); Mehmet Necati Kutlu et al., Osmanlı İmparatorluğu - Latin Amerika - Başlangıç Dönemi (Ankara: Directorate of Ankara University Research Center for Latin American Studies, 2012).

- Bernard Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey, (Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002 [III ed.]).

- Manuel Moreno Fraginals, El Ingenio: Complejo Económico Social Cubano del Azúcar (Havana: Editorial Ciencias Sociales, 1978), p. 259.

- Kristin Ruggiero, The Jewish Diaspora in Latin America and the Caribbean: Fragments of Memory (Portland: Sussex Academic Press, 2005).

- The number of Arab immigrants arriving in Cuba between 1870 and 1900 was at approximately two thousand. Rigoberto D. Paredes, Componentes Arabes En La Cultura Cubana (Havana: Ediciones Boloňa, 1999).

- Nazan Çiçek, “Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ve Küba İlişkilerinin Başlangıcı,” Osmanlı İmparatorluğu-Latin Amerika (Başlangıç Dönemi), (Ankara: Latin Amerika Çalışmaları Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Yayınları, 2012), p. 70.

- Ignacio Klich and Jeffrey Lesser, “Introduction: ‘Turco’ Immigrants in Latin America,” The Americas, Vol. 53, No. 1 (1996).

- The Arab population living in Cuba in 1916 was estimated at between nine and ten thousand, with Syrians constituting the main group, approximately 65 percent.

- By the end of 1924 the Jewish community in Cuba had reached approximately twenty-four thousand, but most of them were from Russia and Poland. Robert M. Levine, Tropical Diaspora: The Jewish Experience in Cuba (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1993).

- Margarita Cervantes-Rodriguez, International Migration in Cuba: Accumulation, Imperial Designs, and Transnational Social Fields (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010).

- Ignacio Klich and Jeffrey Lesser, Arab and Jewish Immigrants in Latin America: Images and Realities (Abingdon: Routledge, 1998).

- Cervantes-Rodriguez, International Migration in Cuba: Accumulation, Imperial Designs, and Transnational Social Fields, p. 139.

- Mount Qaf is a mysterious mountain of ancient Islamic tradition renowned as the ‘farthest point of the earth,’ also have been numerously noted in Middle Eastern fairy tales as a place which cannot be reached by mankind.

- For details, please visit the website of Turkey’s Havana Embassy, http://havana.be.mfa.gov.tr/

Mission.aspx. - William Hale, Turkish Foreign Policy, 1774-2000 (Portland/London: Frank Cass, 2000).

- “Executed Agreement through exchanged letters for the Improvement of the existing visa regime between the Republic of Turkey and the Republic of Cuba in order to allow Turkish Diplomatic, Special and Service Passport Holders and Cuban Diplomatic and Official and Service Passport Holders to be subject to visa exemption for up to 90 days of their visits in one another’s countries.” Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Küba Cumhuriyeti Arasında Mevcut Vize Rejiminin İyileştirilmesi Amacıyla Türk Diplomatik, Hususi ve Hizmet Pasaportu Hamili Kişiler ile Küba Diplomatik, Resmi ve Hizmet Pasaportu Hamili Kişilerin Birbirlerinin Ülkelerine Yapacakları 90 Güne Kadar Olan Seyahatlerde Vizeden Muaf Tutulmalarına İlişkin İki Ülke Arasında Mektup Teatisi Yoluyla Akdedilen Anlaşma. For details please visit, Ministry of Foreign Affairs International Agreements: http://ua.mfa.gov.tr/detay.aspx?4743

- For details please visit, Ministry of Foreign Affairs International Agreements: http://ua.mfa.gov.tr/detay.aspx?5698.

- Mehmet Özkan, “Does “Rising Power” Mean “Rising Donor”? Turkey’s Development Aid in Africa,” Africa Review, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2013), p. 142.

- Ariel S. González Levaggi, “América Latina y Caribe, la Ultima Frontera de la ‘Nueva’ Política Exterior de Turquía,” Araucaria Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, Vol. 14, No. 28 (2012).

- Turkey’s sole foreign policy destination must be towards the West. See Erman Akıllı, Türkiye’de Devlet Kimligi ve Dis Politika (Ankara: Nobel Yayinlari, 2013), p. 44-45.

- Kemal Kirişci, “The Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy: The Rise of the Trading State,” New Perspectives on Turkey, Vol. 40, No. 1 (2009).

- After the USSR’s dissolution, the very first opening in Turkish Foreign Policy was a widening foreign policy towards the Central Asian young Turkic States. See Ziya Öniş, “Multiple Faces of the ‘New’ Turkish Foreign Policy: Underlying Dynamics and a Critique,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 1 (2011).

- Akıllı, Türkiye’de Devlet Kimligi ve Dis Politika, pp. 57-71.

- From the very foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, to the 1990s, Turkish Foreign Policy was forced to be single-focused, and had the sole destination of going along with the US, the European Union, and NATO. Of course, this type of unidirectional foreign policy understanding takes its roots from Turkey’s western-oriented state identity. See, Akıllı, Türkiye’de Devlet Kimligi ve Dis Politika.

- Burak Küntay, “Türkiye’nin Yeni Dış Politikası Perspektifinde Latin Amerika ile İlişkileri,” in Zengin Ozan (ed.), Latin Amerika Çalıştayı Bildiri Kitabı (Ankara: Ankara Üniversitesi Latin Amerika Çalışmaları Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Yayınları, 2013), p. 148.

- Ariel S. González Levaggi, “Turkey and Latin America: A New Horizon for a Strategic Relationship,” Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 18, Issue 4, (2013), p. 108.

- “Başbakan Erdoğan Meksika’da!,” Hurriyet, retrieved from http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/basbakan-

Erdoğan-meksikada-13160387. - “Başbakan Erdoğan Brezilya’da!,” Sabah, retrieved from http://www.sabah.com.tr/gundem/2010/

05/26/basbakan_Erdoğan_brezilyada. - “Arjantin ile ‘Los Turcos’ Bağı,” Hurriyet, retrieved from http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/arjantin-le-los-

turcos-bagi-16815325. - “Lula Da Silva Türkiye’ye Geliyor!,” Sabah, retrieved from http://www.sabah.com.tr/dunya/2009/05/

20/lula_da_silva_turkiyeye_geliyor. - “Brezilya Cumhurbaşkanı Türkiye’ye Geliyor!,” retrieved from http://www.haberler.com/brezilya-

cumhurbaskani-turkiye-ye-geliyor-2-3040521-haberi/. - “Bizi Birleştiren Köprü Dostluk,” retrieved from http://www.costaricaconsulistanbul.com/OPSpeeches_Dinner.aspx.

- “Gül ve Santos Basın Toplantısı Düzenledi,” Anadolu Ajansı, retrieved from http://aa.com.tr/tr/pg/foto-galeri/gul-santos-basin-toplantisi-/0

- President Erdoğan’s last visit to Chile, Peru and Ecuador in February 2016 also underlines the importance of the region for Turkey’s foreign policy. For details please visit: http://www.tccb.gov.tr/haberler/410/38661/cumhurbaskani-Erdoğan-siliye-gitti.html.

- “Relations between Turkey and the Republic of Cuba,” Turkish Republic of State Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-turkey-and-republic-of-cuba.en.mfa.

- Büyükelçi Ernesto Gomez Abascal: “İlişkilerimizde En Güzel Zaman Yaşanıyor,” Diplomat Atlas, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.diplomat.com.tr/atlas/sayilar/sayi4/sayfalar.asp?link=s4-4.htm.

- “Turkey’s Erdoğan: US Sanctions on Cuba ‘not Right’,” Turkey Agenda, 27 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.turkeyagenda.com/turkeys-Erdoğan-us-sanctions-on-cuba-not-right-1977.html.

- “Turkey, Cuba to Boost Bilateral Relations,” World Bulletin, 9 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.worldbulletin.net/turkey/154647/more-former-turkish-policemen-detained-for-illegal-wiretapping?utm_content=buffer49160&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer.

- Cuba State Profile, Turkish Republic of State Ministry of Economy, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.ekonomi.gov.tr/portal/faces/home/disIliskiler/ulkeler/ulke-detay/K%C3%BCba/html-viewer-ulkeler?contentId=UCM%23dDocName%3AEK-160443&contentTitle=D%C4%B1%C5%9F%20Ticaret&_afrLoop=2934363986486197&_afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId=null#!%40%40%3F_afrWindowId%3Dnull%26_afrLoop%3D2934363986486197%26contentId%3DUCM%2523dDocName%253AEK-160443%26contentTitle%3DD%25C4%25B1%25C5%259F%2BTicaret%26_afrWindowMode%3D0%26_adf.ctrl-state%3Duq3g5aavt_410

- “Relations between Turkey and the Republic of Cuba”, Turkish Republic of State Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved May 07, 2015 from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-turkey-and-republic-of-cuba.en.mfa.

- News and Comments on Turkey 9-13 February 2015, AK Party Foreign Affairs Office Press Release, retrieved May 10, 2015 from http://images.akparti.org.tr/upload/bulten/News-and-Comments-on-Turkey_9-13February-2015.pdf.

- For details please visit: Turkish Embassy in Havana, retrieved from havana.be.mfa.gov.tr/images/.../1/5be2c19f-e723-4e44-8b67-174c7bbfa0a0.docx.

- “Cuban Investment Law Came into Force,” Periodico26.cu, 28 June 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.periodico26.cu/index.php/en/cuba-news/20465-cuban-investment-law-comes-into-force.

- “Turkey is Interested in Investing in Cuban Economic Sectors,” Radio Cadena Agramonte, 13 February 2015, retrieved May 07, 2015 from http://linkis.com/icrt.cu/RAHaC.

- “Latin Amerika Açılımıyla Ticaret de Şaha Kalkacak,” Aksam, 13 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.aksam.com.tr/ekonomi/latin-amerika-acilimiyla-c2ticaret-de-saha-kalkacak/haber-381785.

- A.A.V.V. TIKA: Latin Amerika Proje ve Faaliyetler, Ankara, 2014, p. 47.

- “Küba’da Yayımlanan ilk Türk Dergisi,” Haber 7, 7 February 2015, retrieved May 10, 2015 from http://www.haber7.com/dergiler/haber/1125248-kubada-yayimlanan-ilk-turk-dergisi.

- “Ask-i Nebi” exhibition in Havana, TRT English, 17 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.trt.net.tr/english/culture-arts/2015/02/17/a%C5%9Fk-%C4%B1-nebi-exhibition-in-havana-166719.

- “‘Aşk-ı Nebi’ Exhibition Travelling the World,” Daily Sabah, 18 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.dailysabah.com/arts-culture/2015/02/18/aski-nebi-exhibition-travelling-the-world.

- “Turkey’s Erdoğan Proposes Building Mosque in Cuba,” Reuters, 12 February 2015, retrieved May 07, 2015 from http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/02/12/us-turkey-cuba-mosque-idUSKBN0LG1E220150212.

- “First Latin American Countries Muslim Leaders Summit Ends,” Republic of Turkey Presidency of Religious Affairs, 15 November 2014, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.diyanet.gov.tr/en/content/first-latin-american-countries-muslim-leaders-summit-ends/22358.

- “Erdoğan Presents Ortaköy Mosque Project to Cuban Authorities,” Daily Sabah, 12 February

2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.dailysabah.com/politics/2015/02/12/Erdoğan-presents-

ortakoy-mosque-project-to-cuban-authorities. - “Turkish President Erdoğan Presents Cuba Mosque Project to Castro”, Hürriyet Daily News, 27 February 2015, retrieved May 10, 2015 from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-president-Erdoğan-presents-cuba-mosque-project-to-castro.aspx?pageID=238&nID=78254&NewsCatID=338.

- “We do not Find Sanctions over Cuba Right in Both Humane and Conscientious Sense,” Presidency of the Republic of Turkey, 11 February 2015, retrieved May 10, 2015 from http://www.tccb.gov.tr/news/397/92289/we-do-not-find-sanctions-over-cuba-right-in-both-humane-and-conscientious-sense.html.

- USC Center for Public Diplomacy, “Ahmet Davutoğlu Conducts ‘Mosque Diplomacy’ in Balkans,” retrieved from http://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/tags/mosque-diplomacy.

- “Davutoğlu Attends Reopening of Historic Bosnian Mosque,” Daily Sabah, retrieved May 25,

2016 from http://www.dailysabah.com/diplomacy/2016/05/07/davutoglu-attends-reopening-of-

historic-bosnian-mosque. - “Turkey’s Erdoğan Wants to Build a Mosque in Cuba. It’s based on a Historical Fallacy,” The Washington Post, 12 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2015/02/12/turkeys-Erdoğan-wants-to-build-a-mosque-in-cuba-its-based-on-a-historical-fallacy/.

- “Why is Erdoğan Asking Cuba to Let Him Build a Mosque in Havana?” The Jerusalem Post, 12

February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Why-is-Erdoğan-

asking-Cuba-to-let-him-build-a-mosque-in-Havana-390833. - “Turkey, Saudi Arabia Compete over Cuba Mosque Project: Erdoğan Determined to Build Havana

Mosque Alone,” International Business Times, 1 March 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.ibtimes.com/turkey-saudi-arabia-compete-over-cuba-mosque-project-Erdoğan-determined-build-havana-1815560. - “Turkey’s Mosque-Building Diplomacy,” Al-Monitor, Turkey Pulse, 13 February 2015, retrieved May 13, 2015 from http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/02/turkey-mosque-building-soft-power.html#.

- Mehmet Özkan, “Turkey’s Religious Diplomacy toward Latin America,” Daily Sabah, November 14, 2014, http://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/2014/11/14/turkeys-religious-diplomacy-toward-latin-america.

- Alessia Chiriatti et al., The Depth of Turkish Geopolitics in the AKP’s Foreign Policy: From Europe to an Extended Neighborhood (Perugia: Università per Stranieri di Perugia, 2015).

- Sadık Ünay, “Turkey’s Emerging Power Politics in Latin America,” Daily Sabah, February 14, 2015,

http://www.dailysabah.com/columns/sadik_unay/2015/02/14/turkeys-emerging-power-politics-in-

latin-america