Introduction

As regularly noted in academic sources and regional analyses, Turkey is situated at the crossroads of several regions that were historically dominated or targeted by Ottoman rulers. Regardless of what the leadership of post-Ottoman Turkey may have intended, the country has always been sensitive to political developments in the Middle East, the Balkans, the wider Black Sea region and the Mediterranean. Although never part of the Ottoman Empire, post-Soviet Central Asia has garnered equally strong interest among Turkish policymakers, not least because of ethnic, linguistic, and religious commonalities. Yet, Central Asia’s position in Turkish foreign policy has received comparatively scant analytical attention in recent years, in part due to Turkey’s deepening involvement in the Syrian civil war since 2013 and the concomitant deterioration in relations with its traditional Western allies. Nevertheless, despite foreign policy failures close to its own borders, Turkey has developed and maintained mostly positive relations with the Central Asian republics.

This commentary provides an overview of Turkish foreign policy in Central Asia and aims to shed light on Ankara’s multifaceted approach to the region. Our main argument is that Turkey’s Central Asia policy –although initially shaped by a romanticized and unrealistic pan-Turkic worldview– witnessed a fundamental reorientation towards more achievable policy goals from the mid-1990s. While ethnolinguistic identity never completely disappeared from Turkish policy vis-à-vis Central Asia, Turkey has largely dispensed with its pan-Turkic aspirations and has increasingly relied on a sophisticated combination of bilateral relations, multilateral institutions, economic linkages, and soft power initiatives to further its aims in the region.

The End of the Soviet Union: A Turning Point in Turkey-Central Asia Relations

The collapse of the Soviet Union signaled a new era in Turkey-Central Asia relations.1 Now independent and compelled to formulate new foreign policies, the five former Soviet republics with majority Muslim and/or Turkic populations (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan) quickly emerged as potential partners for Turkey. Ankara was among the first to recognize their independence, but despite its eager diplomatic overtures and the ethnic and religious similarities it shared with these newly independent states, Turkey was not yet prepared to forge a strong relationship with the region. The combination of euphory and miscalculation vis-à-vis Central Asia negatively affected Turkey’s initial policy toward the region.

Although Turkey eventually abandoned its romanticized notion of a new Turkic world, Ankara maintained ambitious objectives in Central Asia

As part of the Western Bloc and a member of NATO, Turkey received advice from Western partners in its efforts to formulate a policy toward Central Asia.2 The dominant sentiment in the West was that the Central Asian republics were susceptible to Iranian and/or Saudi religious influence. On the other hand, Turkey –as a secular, relatively democratic, pro-Western, Muslim-majority country– could serve as a positive bridge between this new geopolitical space and the West. This idea was as widespread among high-level policymakers as it was among think tanks and diplomats, and it even received support from then U.S. president George H. W. Bush in 1992.3 In Central Asia, local authorities initially viewed Turkey as a good transition model from a centrally planned economy to a more liberal market-oriented system. Prior to adopting a critical policy toward Turkey, Uzbek President Islam Karimov was among the leaders who supported the idea of a Turkish model for Central Asia.

Despite widespread optimism for the Turkish model, however, Turkey’s initial policy toward Central Asia proved untenable. To be sure, Western encouragement and Central Asian aspirations were overly optimistic and led to unrealistic initial expectations for Turkey. However, Turkey’s sentimental visions of Central Asia bear the most responsibility for the ineffective policy direction. Turkish policymakers and diplomats naively thought that Turkey could cooperate with Central Asia to create –in the words of former President Süleyman Demirel– a new “Turkic World stretching from the Adriatic to the Great Wall of China.” To realize this project, Turkey adopted various symbolic political measures. The first decision was to create a new bloc of countries around the idea of Turkishness and initiate Turkic summits, which gathered the leaders of Turkey and the four Turkic republics of Central Asia annually. These summits proved difficult to organize and Ankara soon realized that it was impossible to adopt political measures or unify participating countries around common principles. Moreover, Turkey was not economically powerful enough to help these countries implement meaningful liberal economic reforms.

Simultaneously, Turkey’s European and American allies realized that there was no significant risk of Central Asia coming under the influence of an Iranian or Saudi model of development, due in part to the deep-rooted secularism in these societies. Western players thus toned down their promotion of the Turkish model and bolstered their own bilateral links with each individual country. For their part, Central Asian leaders knew they could open their countries to the world without Turkish assistance. Turkey likewise acknowledged that the Central Asian countries, despite cultural and religious commonalities, were very heterogeneous and had a range of different priorities in their respective state-building processes. As such, from 1996 onward, Turkey reverted to a more realistic Central Asia policy.

Turkey’s New Priorities in Central Asia

Although Turkey eventually abandoned its romanticized notion of a new Turkic world, Ankara maintained ambitious objectives in Central Asia. To be sure, Turkey did not completely eschew ethnic identity as a basis for developing relations with the Turkic former Soviet republics. However, its position toward the region after 1996 has been underpinned by realistic policy instruments and long-term calculations. In political, economic, cultural, and religious spheres especially, Turkey relies on a sophisticated set of foreign policy tools vis-à-vis Central Asia.

Creating Conditions for Political Dialogue

While it no longer believes in a wide-spanning Turkic union, Turkey continues to cultivate multilateral relations with Central Asian states partially on the basis of ethnolinguistic identity. Turkey has pursued this vector primarily through Türk Keneşi (the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, CCTS, the Turkic Council). The Turkic Council was established in 2009 as an intergovernmental organization with the aim of promoting comprehensive cooperation among Turkic-speaking states. In particular, the organization strives to build political solidarity in the Turkic world and to promote economic and technical cooperation. Its four founding member states are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkey. For its part, Turkmenistan showed no interest in joining the Turkic Council due to the neutrality officially enshrined in its constitution. Uzbekistan also forewent membership, but with the accession of Shavkat Mirziyoyev to the presidency in 2016, Tashkent began opting for a more open foreign policy and in April 2018 announced its intention to join the body.4

In tandem with this soft “pan-Turkist” integration project, which essentially treats Central Asia as a single entity, Turkey has developed a keen awareness of local regimes, populations and ethnonationalist aspirations. As such, Ankara has concurrently refocused its foreign policy on strengthening bilateral relations with each of these countries.5

As previously mentioned, Turkey initially aspired toward a single, integrated policy vis-à-vis Central Asia on account of the region’s ethnic and religious similarities. It took some time before Ankara fully appreciated that the Soviet policy of ethnonational identity construction had been successful in the sense that Soviet authorities had managed to engineer new national identities in form, if not initially in content. Having realized the import and ultimate reification of local national identities, Turkey dispensed with its evocation of a common Turkic legacy. It also began praising the respective national identities and nation-building policies of each country.

Another important aspect of Turkey’s political ambitions in Central Asia is its support for the ruling regimes. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Turkey was tempted to throw its backing behind Central Asia’s most nationalist and Turkist political forces who shared Turkey’s initial conception of a wider Turkic union. However, these forces were rapidly marginalized. In Uzbekistan, the two main nationalist parties –Birlik and Erk– soon faced repression from the Karimov government.6 In Azerbaijan, the staunch nationalist Abulfaz Elchibey led the Azerbaijani Popular Front Party (APFP) to power in 1992 and as president advocated close relations with Turkey. Elchibey and the APFP, however, were toppled during a coup d’état in 1993.7 Recognizing the marginalization of these pro-Turkic forces, Turkey did not hesitate to provide support to the regimes that ultimately came to power, even if these regimes did not give Turkey sole priority in their foreign policy.

Frequent high-level political visits by Turkish leaders to Central Asia constitute yet another important aspect of Turkey’s political relations with the region. Since 1991, all Turkish presidents and prime ministers have visited each country in Central Asia on a regular basis and have been warmly received. Despite commonly held perceptions that Turkey was more interested in Europe and the Middle East, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has never neglected the Turkic countries and has visited them on a regular basis over the past two decades.

Turkey’s Economic Relations with Central Asia

Since the demise of the Soviet Union, the Caspian Basin and Central Asia have piqued the interest of Turkish leaders both in terms of energy resources and potential markets for Turkish enterprises. Thanks to very intensive diplomacy and negotiations between Turkey, Azerbaijan, the United States, Georgia, and major international oil companies, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline was commissioned in 2005 to transport crude oil from the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli field offshore Azerbaijan to international markets via the Turkish terminal of Ceyhan.8 Initially, the pipeline exported only Azerbaijani oil, although Kazakhstan began exporting crude oil from its Tengiz field via the BTC in late 20089 and Turkmenistan began exports through the pipeline in 2010.10 Turkey’s interests in the energy sphere also extend to natural gas. In mid-2018, the presidents of Turkey, Georgia, and Azerbaijan jointly inaugurated the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), which is slated to deliver six billion cubic meters (bcm) of Azerbaijani gas to Turkey annually and an additional ten bcm per year to various destinations in Europe via Turkey. TANAP will thus help Turkey realize its goal of becoming a natural gas hub, as well as diversify its own supply slightly away from Russia and Iran.11

Thanks to TİKA’s activities in Central Asia, Turkey acquired valuable experience in the field of international development and TİKA subsequently capitalized on its experience in the former Soviet Union to become an instrument of cooperation for Turkey in other developing countries

Turkey has also taken a keen interest in economic development in Central Asia. Indeed, the Turkish Agency for Cooperation and Development (TİKA) began operating just after the collapse of the Soviet Union and has pursued various initiatives in the region, ranging from cultural and archaeological cooperation to infrastructure. Thanks to TİKA’s activities in Central Asia, Turkey acquired valuable experience in the field of international development and TİKA subsequently capitalized on its experience in the former Soviet Union to become an instrument of cooperation for Turkey in other developing countries.

Although dwarfed by trade volumes with Europe, Turkey’s economic relations with Central Asia are quite dynamic and multifaceted. Most importantly, Turkey is a well-placed trading partner for countries attempting to foster more vibrant private sectors, in the sense that the majority of Turkish companies in Central Asia are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that serve to strengthen human relations between the two regions. In addition to SMEs, the Turkish construction sector maintains an important economic presence in Central Asia. Following independence, Central Asian countries needed significant new infrastructure upgrades, and major Turkish construction companies emerged as crucial players in the development of the construction sector throughout the region. Notably, enormous infrastructure outlays transformed Turkmenistan’s capital of Ashgabat into a veritable construction site, with French Bouygues companies competing with major Turkish players such as Polimeks, Net Yapı/Nata Holding, Engin Grup, and Cotam.

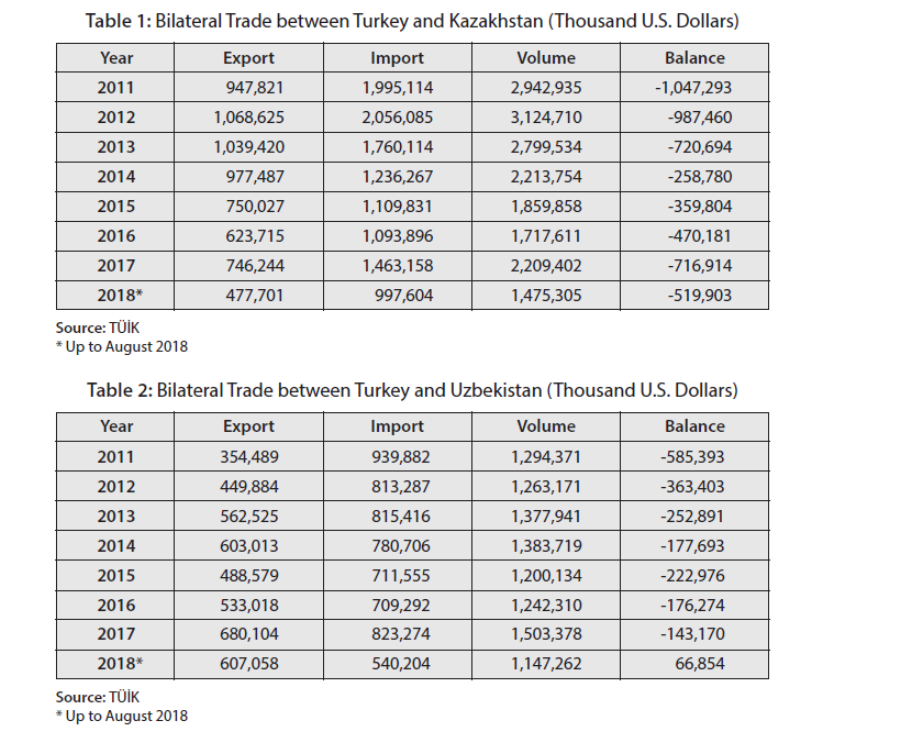

In terms of trade volumes with Turkey, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan deserve special attention. The value of trade volumes between Turkey and Kazakhstan stood at $2.2 billion in 2017, with projects of Turkish construction firms active in Kazakhstan exceeding $21 billion. Moreover, Turkish business people have contributed to Kazakhstan’s development since the early days of independence and there are currently around 600 Turkish companies registered in Kazakhstan.12

Trade between Turkey and Uzbekistan has increased steadily since the 2000s and could potentially show renewed growth considering the marked improvement in bilateral relations since 2016. Trade volumes amounted to approximately $1.7 billion in 2015, with investments by Turkish firms exceeding $1 billion. Indeed, 519 companies with Turkish capital are reportedly registered in Uzbekistan, where they are engaged in textile production, hospitality management, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing (e.g. building materials and plastics), and the services sector.13

Turkey-Central Asia Relations in the Cultural Sphere

In the educational and cultural spheres, Turkey has pursued various initiatives to strengthen relations with the Central Asian republics. Most significant, perhaps, was Turkey’s encouragement to abandon the Cyrillic alphabet in favor of a Latin alphabet.14 Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan adopted Latin-based alphabets relatively early, while Kazakhstan recently approved a decree for a new alphabet. Having shifted from an Arabic to a Latin alphabet earlier in the 20th century, Turkey provided technical assistance for this reform and served as an example for similar changes in Central Asia. Under the supervision of the Turkish Language Association and the Ministry of Culture, several committees in Turkey even formulated and proposed a new “common Turkic alphabet” to the post-Soviet states.15 While Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan did not adopt this exact variant, their respective alphabets were in fact quite close to the proposed common alphabet. In any case, alphabet reform in Central Asia was a success for Turkey, insomuch as these reforms have facilitated more effective communication.

Through various educational programs and the establishment of Turkish schools in Central Asia, Turkey has indirectly groomed a new generation of local business and political elites capable of strengthening ties with the region

In order to foster cultural exchange with Central Asia, Turkey spearheaded the creation of the International Organization of Turkic Culture (TURKSOY). Established in 1993 by Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Turkey, TURKSOY is essentially a Turkic equivalent of UNESCO. It has carried out activities to strengthen cultural ties among Eurasia’s Turkic populations and promote Turkic culture more broadly on the global stage. The organization has worked in conjunction with various ministries, municipalities, and private organizations, and as a result it has cultivated a better mutual understanding between Turkey and Central Asia. Whereas the communist Turkish poet Nazım Hikmet was one of the few cultural links between Turkey and Central Asia during the Soviet period, for example, TURKSOY’s activities have led to a greater appreciation for prominent Central Asian intellectual figures such as Olzhas Suleymanov, Abdulla Aripov, and Chinghiz Aitmatov within Turkey.

In addition to TURKSOY’s initiatives, Turkey has achieved notable success in the field of education. Indeed, through various educational programs and the establishment of Turkish schools in Central Asia, Turkey has indirectly groomed a new generation of local business and political elites capable of strengthening ties with the region. Concretely, Turkey took significant steps to host Central Asian students in Turkey, send Turkish students to study in Central Asia, and establish schools and universities in the region that are well regarded for their quality of instruction.

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, the second-longest oil pipeline in the former Soviet Union, transports oil to Turkey’s southeastern city of Ceyhan, some of which is further delivered to other countries. YUSUF TUNUR / AA Photo

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, the second-longest oil pipeline in the former Soviet Union, transports oil to Turkey’s southeastern city of Ceyhan, some of which is further delivered to other countries. YUSUF TUNUR / AA Photo

Just after the end of the Soviet Union, Turkey’s Ministry of Education formulated a very ambitious program dubbed the “Big Student Project.” The aim of the program was to simplify the process of applying for and matriculating into Turkish universities for Central Asian students. Thousands of students from Central Asia and Azerbaijan subsequently received scholarships to study in various Turkish institutions of higher learning. The implementation of this program was extremely complex and not always satisfactory. For example, Central Asians sometimes had difficulty adapting to life in Turkey and integrating into Turkish culture, and from an educational standpoint the level of scholarship was in some cases insufficient. On the whole, however, the program allowed thousands of Central Asian students to get firsthand knowledge of Turkey, and their presence in different cities around the country was in itself beneficial to Turkey’s relations with the region.16

In parallel to the “Big Student Project,” Turkey encouraged thousands of Turkish students to pursue studies in Central Asia. The Ministry of Education went so far as to integrate local universities into its system, meaning that diplomas obtained in Central Asia received official recognition in Turkey. Accordingly, thousands of Turkish students learned Central Asian languages and even Russian, and their firsthand experience of Central Asia likewise reinforced Turkey’s relations with the region.

With regard to Turkish educational institutions in Central Asia, we should underline the role of two public universities established by Ankara in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The first public Turkish university to begin operations in Central Asia was Ahmet Yesevi, located in the southern Kazakh city of Turkistan with branches in Shymkent and Kentau.17 The choice of name and location in Turkistan was not coincidental. Indeed, in their initial bid to evoke a feeling of brotherhood with Central Asia in the early 1990s, Turkish policymakers drew on the spiritual figure of Ahmet Yesevi (1093-1166), who played an important role in the development of an Islamic mysticism common to both Central Asia and Anatolia.18 Located in the vicinity of Yesevi’s Mausoleum in Turkistan, the university has educated numerous new Kazakhstani elites and continues to play an important role in Turkey’s bilateral relations with the country. In a similar vein, Turkey created Manas University in Kyrgyzstan in 1995. The university’s name harkens back to the Epic of Manas, a major literary work that describes the feats of a key figure in the history and national identity of Kyrgyzstan.19 This university is among the best in the country and vies with both the American University of Central Asia and the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University for academic preeminence.

As a result of this multi-pronged strategy, Diyanet has successfully diffused a Turkish variant of Islam in Central Asia, which is anchored squarely in the Hanafi school of jurisprudence and the teachings of al-Maturidi, and coexists harmoniously with state structures

Turkey’s successes are even more visible in the field of religious cooperation. Despite Western encouragement to export Turkey’s secular transition model to Central Asia in the 1990s, Turkey’s initiatives in the field of religion did not exactly emphasize the country’s secular experience. Rather, Turkey exported its vision of Islam to the region and has emerged as a crucial player in the reshaping of Islam in the post-Soviet sphere. In that sense, Turkey has successfully competed with other Islamic countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, and potentially prevented the spread of more fundamentalist strains of Islam in the region.

Turkey’s religious policy is multifaceted and has been furthered by a range of public and private actors. The main public institution behind Turkish religious policy in the post-Soviet period is Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı (Directorate of Religious Affairs, Diyanet). Diyanet, which essentially functions as a Ministry of Religious Affairs, was traditionally a minor actor in Turkish foreign policy.20 Diyanet maintains a presence in Central Asia through education, mosque construction, and the distribution of religious literature.21 In the field of education, Diyanet has hosted hundreds of Central Asian students in the Faculty of Theology at Marmara University, providing them with scholarships and stipends as well as a high level of religious education. Similarly, Diyanet has established several faculties of theology in Central Asia. The faculties established in Ashgabat, Osh (Kyrgyzstan), Shymkent, and Baku and have played an important role in the education of local religious cadres.

Meanwhile, several mosques have been renovated or constructed with Diyanet’s support. In Kyrgyzstan, Diyanet funded the construction of the Bishkek Central Mosque of Imam Sarakhsi. President Erdoğan attended its inauguration in 2018;22 it is currently Central Asia’s largest place of worship.23 In Ashgabat, Diyanet’s policy resulted in the construction of one of Turkmenistan’s largest mosques. Finally, Diyanet has distributed abundant amounts of religious literature in local languages to provide Central Asians with a better basis in Islamic education. As a result of this multi-pronged strategy, Diyanet has successfully diffused a Turkish variant of Islam in Central Asia, which is anchored squarely in the Hanafi school of jurisprudence and the teachings of al-Maturidi, and coexists harmoniously with state structures.

Diyanet is not the only actor that has contributed to the diffusion of Hanafi Sunnism in the region. Turkish non-governmental organizations –particularly in the form of religious orders– have also played a crucial role. For context, such Turkish religious orders owe many of their fundamental tenants to the region, given that many features of Islam in Anatolia originated in Central Asia. This historic religious link has led to many similarities in Anatolian and Central Asian variants of Islam, particularly in terms of Sufism. Indeed, the very famous Naqshbandiyah Order, which has been active in Turkey since the Middle Ages, originated in present-day Uzbekistan. Up until the early 20th century, representatives of this order often traveled across Eurasia and the Indian Subcontinent to patronize different Naqshbandiya branches,24 although such relations were severely curtailed during Soviet times. Since the 1990s, however, connections between Central Asian and various Naqshbandiyah branches globally have been rejuvenated. The most prominent Turkish Naqshbandiyah branch active in Central Asia is that of Osman Nuri Topbaş. With the support of an associated foundation (Aziz Mahmud Hüdayi Vakfı), this respected religious leader and his representatives established small cultural and religious centers that have played an important role in the revival of Islam throughout Central Asia. This community has been very active in various cities in Kazakhstan in particular, where its initiatives range from humanitarian aid to education and the training of new spiritual leaders.

Likewise, a Turkish Naqshbandiya order under the spiritual guidance of Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan has cultivated a keen interest in Central Asia. Well known for its Quran courses in Turkey,25 Tunahan’s order has always prioritized improving literacy in Arabic to read the Quran, which they view as a core requirement of being a true Muslim. Funding new opportunities for growth in Central Asian states, Tunahan’s community has been especially active in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, where it has established several small madrasas and trained new imams who are now active in various parts of Eurasia.

The more fundamental sticking point in Turkey-Uzbekistan relations can be traced to Uzbekistan’s own preferences in the spheres of foreign policy and state building

Finally, the followers of Said Nursi have likewise figured prominently among Turkish spiritual NGOs active in Central Asia. This religious community has various branches that specialize in different activities such as education, charitable initiatives and research, among others.26 In Central Asia, Nursi’s followers –particularly groups associated with Mustafa Sungur and Mehmet Kutlular– have established several informal madrasas and religious circles.

In summary, Turkey’s religious activities in Central Asia have had two effects. From an official policy standpoint, Turkey has utilized Islam as a foreign policy instrument to reinforce its bilateral relations with regional states. Thanks to Turkey’s multi-actor strategy, moreover, Turkish NGOs have contributed to the development of a moderate Islam in the region. Turkey’s combination of political, educational, religious, and economic initiatives vis-à-vis Central Asia have thus made Ankara a major actor in a region where Turkish influence has been almost completely absent for most of the 20th century. More recently, two major developments could have important ramifications for Turkey’s role in Central Asia, namely the sudden improvement of bilateral relations between Turkey and Uzbekistan, and the negative fallout from the actions of Gülenists in Turkey in 2016.

Recent Developments in Turkey-Central Asia Relations

The Uzbek Opening: Implications for Bilateral Relations

Turkey’s bilateral relations with Uzbekistan deserve special attention, given Uzbekistan’s sizeable population and consequential geopolitical position. Likewise, the country arguably has the richest legacy in the region in terms of history and intellectual heritage. Like other states, Turkey prioritized relations with Uzbekistan immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union.27 Bilateral relations were quite positive during the first years of independence and were bolstered by excellent personal relations between Uzbek President Islam Karimov and his Turkish counterparts Turgut Özal and Süleyman Demirel.

Nevertheless, Turkey-Uzbekistan relations soon faced serious challenges for two reasons. Firstly, Uzbek opposition leaders Muhammad Salih and Abdurahim Pulatov took refuge in Turkey in the early 1990s after facing increasing repression from Karimov’s government. Although Turkey did not officially grant them asylum, Salih’s and Pulatov’s presence was tolerated and, in any case, Turkish legislation did not allow for their extradition back to Uzbekistan despite frequent demands from Tashkent. To be sure, Turkey maintained its support for Uzbekistan’s ruling regime, which was consistent with its approach to Central Asia. Nevertheless, the dominant sentiment in Tashkent was that Turkey was being duplicitous, on the one hand helping the opposition while also striving toward positive relations with Tashkent.

Presidents of the Turkic Council member states meet in Kyrgyzstan on September 3, 2018. CEM ÖKSÜZ / AA Photo

Presidents of the Turkic Council member states meet in Kyrgyzstan on September 3, 2018. CEM ÖKSÜZ / AA Photo

The second and more fundamental sticking point in Turkey-Uzbekistan relations can be traced to Uzbekistan’s own preferences in the spheres of foreign policy and state building. Under Karimov’s presidency (1991-2016), isolationism was a fundamental characteristic of Uzbekistan’s foreign policy.28 In its bid to shield the Uzbek nation-building process from external influences, Karimov’s government chose to limit its relations with many countries. Uzbekistan even forewent deeper relations with countries such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia, which both hosted large Uzbek diasporas that could have conceivably served as lobbying forces.29 With regards to Turkey specifically, Uzbekistan saw Turkish religious and national influences as a threat to the unique character of the nascent Uzbek nation-state. When Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power following Karimov’s death in 2016, Turkey’s bilateral relations with the regional heavyweight improved rapidly. Mirziyoyev twice visited Turkey as the head of high-level delegations, and Turkish President Erdoğan made a state visit to Uzbekistan.30 In yet another harbinger of possible improvements to come, Uzbekistan implemented a visa-free travel regime for Turkish citizens, not an insignificant step considering Uzbekistan’s traditional sensitivity to the presence of foreigners on its territory.31

The Gülen Factor: From Soft Power to Political Violence

Another important development in Turkey-Central Asia relations involves the Gülenist organization, an opaque Islamic network that supports educational and commercial initiatives and adheres to the teachings of Fetullah Gülen. The organization first came to Central Asia just after the end of the Soviet Union, although local regimes were initially hesitant to host Gülenists and their array of organizations, commercial enterprises, media outlets and schools due to their unclear organizational structure. Likewise, Turkish diplomats regarded the Gülenist Terrorist Organization’s (FETÖ) initial activities in Central Asia with some suspicion and even embarrassment.32 Nevertheless, various enterprises linked to Gülen managed to establish and patronize new schools throughout Central Asia, thanks largely to the support of then-President Turgut Özal, who viewed such educational institutions as effective instruments of soft power. Özal’s successors strengthened Gülen-linked organizations in Central Asia by continuing this supportive policy, although in 1999 Uzbekistan closed schools related to the organization and expelled all of Gülen’s representatives. Turkmenistan followed suit in 2011 and shuttered Gülenist schools, and Russia did the same by closing Gülenists’ schools in the Russian Federation.

The Gülenist organization was able to pursue its initiatives in Central Asia with relative ease as long as it remained on good terms with the Turkish government and kept its involvement in domestic politics to a minimum. However, the organization became increasingly politicized in Turkey starting in 2013, and developed a more confrontational relationship with the political establishment. The July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey signaled a watershed for the organization, both in Turkey and Central Asia.33 Because of its involvement in the coup attempt, FETÖ was declared a terrorist organization –dubbed the Gülenist Terrorist Organization– and its activities in Turkey were banned. Its image in large Central Asia was also tarnished, and authorities in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan closed FETÖ schools at Ankara’s urging. Kyrgyzstan has been less inclined to follow Turkey’s directives, although local authorities changed the name and status of the schools and they are now under strict surveillance.

Conclusion

Following initial disappointments in the early 1990s, Turkish foreign policy vis-à-vis Central Asia has witnessed numerous successes thanks to its reorientation toward more realistic policy aims. Indeed, immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Turkish policymakers viewed the region through a wider prism of Turkism. Although historically true, this romanticized vision did not reflect the transformation of national identities that had taken place in Central Asia during the Soviet period. While respectful of the notions of Turk, Turkestan, and Turkishness, Central Asians had become significantly more attached to their national identities, whether Uzbek, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, or Turkmen. Once Ankara recognized the realities on the ground and began respecting these national identities, its policies in the region grew significantly more successful.

Due to the precarious international and regional contexts, moreover, Turkey will certainly devote more attention to its Central Asian policy in the years to come. Turkey’s stalled EU membership bid and the general deterioration of its relations with Western partners could catalyze this process. Similarly, the myriad of conflicts in the Middle East that negatively impact Turkey’s image and partnerships in the region will likely compel Ankara to pursue deeper relations with Central Asia. Finally, this deepening of bilateral relations could receive tacit support from Russia, considering Ankara’s ongoing rapprochement with Moscow in recent years.

Endnotes

- Touraj Atabaki and John O’Kane, Post-Soviet Central Asia, (London: I. B. Tauris, 1998), p. 342.

- Mustafa Aydin, “Foucault’s Pendulum: Turkey in Central Asia and the Caucasus,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2004), pp. 1-22.

- İdris Bal, “Turkey’s Relations with the West and the Turkic Republics: The Rise and Fall of the ‘Turkish Model’,” (Farnham: Ashgate, 2008), p. 232. See also, Emel Parlar Dal, and Emre Erşen, “Reassessing the ‘Turkish Model’ in the Post-Cold War Era: A Role Theory Perspective,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2 (2014), pp. 258-282.

- “Uzbekistan Decides to Join ‘Turkic Alliance’ during Erdogan’s Visit,” Hürriyet Daily News, (April 30, 2018), retrieved August 10, 2018, from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/uzbekistan-decides-to-join-turkic-alliance-during-erdogans-visit-131109.

- Ertan Efegil, “Turkish AK Party’s Central Asia and Caucasus Policies: Critiques and Suggestions,” Caucasian Review of International Affairs, Vol. 2, No. 3 (2008), pp. 166-172, retrieved from http://www.cria-online.org4_6.html.

- Neil J. Melvin, Uzbekistan: Transition to Authoritarianism on the Silk Road (Postcommunist States and Nations), (London: Taylor & Francis, 2000), p. 192.

- Svante Cornell, Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 480.

- Pınar İpek, “The Aftermath of Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline: Challenges Ahead for Turkey,” SAM Center for Strategic Research, (Spring 2006), retrieved from http://sam.gov.tr/tr/the-aftermath-of-baku-tbilisi-ceyhan-pipeline-challenges-ahead-for-turkey/.

- “Tengiz Crude Starts Flowing in BTC Pipeline-Source,” Reuters, (October 29, 2008), retrieved August 10, 2018, from https://ru.reuters.com/article/idUKLT40257120081029.

- “Turkmen Oil Starts Flowing Through BTC Pipeline,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, (August 12, 2010), retrieved August 10, 2018, from https://www.rferl.org/a/Turkmen_Oil_Starts_Flowing_Through_BTC_Pipeline/2126224.html.

- Georgi Gotev, “Three Presidents Inaugurate TANAP Pipeline in Turkey,” Euractive, (June 12, 2018), retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/three-presidents-inaugurate-tanap-pipeline-in-turkey/.

- “Economic Relations between Turkey and the Republic of Kazakhstan,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/economic-relations-between-turkey-and-republic-of-kazakhstan.en.mfa.

- “Economic Relations between Turkey and Uzbekistan,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/economic-relations-

between-turkey-and-uzbekistan.en.mfa. - William Fierman, “Identity, Symbolism, and the Politics of Language in Central Asia,” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 6, No. 7 (September 2009), pp. 1207-1228.

- Abdulvahap Kara, “Türk Keneşi (Konseyi) ve Türk Dünyasının 34 Harfli Ortak Alfabe Sistem,” Prof. Dr. Abdulvahap Kara personal website, (December 7, 2012), retrieved from http://www.abdulvahapkara.com/turk-kenesi-ve-alfabe/.

- Pınar Akçalı and Cennet Engin Demir, “Turkey’s Educational Policies in Central Asia and Caucasus: Perceptions of Policy Makers and Experts,” International Journal of Educational Development, No. 32 (2012), pp. 11-21.

- Göksel Öztürk, “Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’nin Orta Asya Türk Cumhuriyetlerindeki Yüksek Öğretim Kurumları Üzerine Bazı Değerlendirmeler,” TASAM, (October 20, 2010), retrieved from http://www.tasam.org/trTR/Icerik/4236/turkiye_cumhuriyetinin_orta_asya_turk_cumhuriyetlerindeki_yuksek_ogretim_kurumlari_uzerine_bazi_degerlendirmeler.

- Yesevi was not particularly unique in this regard. Turkish policymakers also promoted historical and religious figures such as İbn Sina, Muhammad al-Bukhari and Bhauddin Naqshband, among others, given the respect that Turkic populations in both Anatolia and Central Asia retain for them.

- Karl Reichl, “Oral Epics into the Twenty-First Century: The Case of the Kyrgyz Epic Manas,” American Folklore Society, Vol. 129, No. 513 (Summer 2016), pp. 326-344.

- Şenol Korkut, “The Diyanet of Turkey and Its Activities in Eurasia after the Cold War,” Acta Slavica Iaponica, Vol. 28, (2010), pp. 117-139, retrieved from https://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/47624/1/ASI28_006.pdf.

- Bayram Balcı, Islam in Central Asia and the Caucasus since the Fall of the Soviet Union, (London: Hurst, 2018), pp. 35-68.

- “Erdoğan Inaugurates Central Asia’s Largest Mosque in Kyrgyzstan,” Daily Sabah, (September 2,

2018), retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/religion/2018/09/02/erdogan-inaugurates-

central-asias-largest-mosque-in-kyrgyzstan. - “Turkish Foundation Completes Central Asia’s Largest Mosque in Kyrgyz Capital Bishkek,” Daily Sabah, (June 2017), retrieved August 22, 2018, retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/2017/06/25/turkish-foundation-completes-

central-asias-largest-mosque-in-kyrgyz-capital-bishkek. - Elizabeth Özdalga, “The Naqshbandis in Western and Central Asia,” ISIM Newsletter, No. 6 (2000), retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/15605108.pdf.

- Balcı, Islam in Central Asia and the Caucasus since the Fall of the Soviet Union, pp. 35-68.

- Balcı, Islam in Central Asia and the Caucasus since the Fall of the Soviet Union.

- Adam Balcer, “Between Energy and Soft Pan-

Turkism: Turkey and the Turkic Republics,” Turkish Policy, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Summer 2012), retrieved from http://turkishpolicy.com/Files/ArticlePDF/between-energy-and-soft-pan-turkism-turkey-and-the-turkic-republics-summer-2012-en.pdf. - Bernardo Teles Fazendeiro, “Uzbekistan’s Defensive Self-Reliance: Karimov’s Foreign Policy Legacy,” International Affairs, Vol. 93, No. 2 (March 1, 2017), retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/93/2/409/2981814 pp. 409-427.

- Bayram Balcı, “The Uzbek Community in Saudi Arabia between Assimilation and Renewed Identity,” Revue Europénne des Migrations Internationales, Vol. 19, (2003), p. 316.

- Fuat Shahbazov, “How Will Erdogan’s Recent Visit to Uzbekistan Enhance Turkish-Uzbek Cooperation?” The Diplomat, (May 2018), retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/how-will-erdogans-recent-visit-to-uzbekistan-enhance-turkish-uzbek-cooperation/.

- For detailed information on Turkey-Uzbekistan relations, see, Eşref Yalınkılıçlı, “Time to Mend Turkey’s Decadent Relations with Uzbekistan, Insight Turkey, Vol. 20, No. 4 (2018).

- Bayram Balcı, Orta Asya’da İslam Misyonerleri: Fethullah Gülen Okulları, (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2005).

- Dexter Filkins, “Turkey’s Thirty-Year Coup: Did an Exiled Cleric Try to Overthrow Erdoğan’s Government?” The New Yorker, (October 17, 2016), retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/17/turkeys-thirty-year-coup.