Introduction

There has been an unresolved debate in conflict literature over the influence of domestic factors in the outbreak of conflict between states. Scholars have approached the topic, known as the diversionary theory, from different dimensions.1 They have utilized different methodological tools to verify or refute the assumption that state leaders use foreign conflict to divert attention away from domestic political problems. Yet, despite the unique focus of most of these studies on the same country, namely the United States (U.S.), the results are still inconclusive. And the theory still remains one of the most contested areas of foreign policy studies.

While the diversionary tendencies of the U.S. have been the subject of a host of studies, scholars have also begun to take interest in the reaction of potential targets of diversionary actions from the U.S. The theoretical reasoning guiding this new avenue of research is that it is not enough for U.S. Presidents to have diversionary incentives. If the target behaves strategically by adopting a more cooperative stance, it can sideline such actions. Nevertheless, in a study investigating diversion in the context of strategic conflict avoidance, Fordham has claimed that strategic conflict avoidance might fail if the leaders of some frequent American targets, Iran for example, actually were seeking hostile actions from the U.S. to enhance their domestic legitimacy and international prestige.2Therefore, it is worthwhile not only to observe whether the U.S. diverts against Iran, but also to analyze whether Iran chooses to avoid or reciprocate such U.S. actions.

While Iran has been keen on promoting an anti-American image destined to overthrow the regime, from the American perspective the Iranian regime is a bulwark of political Islam motivated to spread its revolutionary zeal

Equally interesting to analyze is whether Iran, which has viewed the U.S. as its arch-enemy (the “Great Satan,” to use Iran’s epithet) from the first day of the Islamic Revolution, uses conflict with the U.S. as a tool to enhance the theocratic/revolutionary regime in the face of growing domestic discontent with the regime’s economic and political foes.3 Decades of international economic sanctions, which have left a heavy toll on the Iranian economy, aggravated by a growing rift between hardliners and reformist factions within the Iranian political elites, have undermined support for the regime among a restive population demanding broad-based political, social and economic reforms. The use of diversion by Iran, and particularly against the U.S., might not sound so convincing at first as some scholars consider diversion to be an instrument uniquely available to preponderant powers such as the U.S., which can project power at choice across the globe without risking any major U.S. interest. However, it is important to investigate this possibility as experts on U.S.-Iran relations maintain that despite the fact that the pragmatic concerns of the Islamic regime dictate conciliation with the U.S., Iranian leaders would still use ideology as much as the U.S. does to mobilize the support of its domestic audience.4 Abulof, for instance, contends that to ensure its political survival against challenges from the reformers, the Iranian government led by Ahmadinejad used American and European objections to Iran’s nuclear program as an instrument to rally around the flag.5 Another scholar has observed that, although the relations between these two countries have been based on regional and international security and stability concerns, both countries used ideology as a tool to capture support from their domestic audiences.6 Ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, both sides have demonized each other. While Iran has been keen on promoting an anti-American image destined to overthrow the regime, from the American perspective the Iranian regime is a bulwark of political Islam motivated to spread its revolutionary zeal.

Therefore, it is important to systematically show whether the U.S. and Iran use their rivalry to divert attention away from domestic political and economic problems. Inspired by the scholarship on the relation between diversion and rivalry, this paper examines the propensity of the U.S. and Iran to use their rivalry for diversionary purposes from 1990 to 2004.7 In addition, it conducts a test of strategic conflict avoidance by examining whether Iran reciprocates hostile actions from the U.S. or acts more conciliatory to avoid becoming the target of diversion.

The paper proceeds in four steps. Following an introduction of the literature, which demonstrates the relevance of the research questions, the paper presents an argument that seeks to explain the theoretical reasoning behind the link between domestic factors and the dynamics of conflict between Iran and the U.S. The third section of the paper explains the research design and the data for testing and analyzing the implications behind the questions of interest. Finally, before the conclusion, the results of the statistical analysis are presented and their implications are discussed.

Literature Review

Diversion and Strategic Conflict Avoidance

Diversionary theory of conflict rests on the assumption that when confronted with domestic problems, political leaders resort to external conflict to restore internal cohesion and unity. In his survey of the literature on diversionary theory, Levy states that nearly every war in the past two centuries has been attributed by some scholars to state leaders’ desire to improve their domestic standing.8 Although early systematic examination of this hypothesis did not produce consistent empirical support, subsequent research, however, has found results lending support to the argument that state leaders use conflict abroad to divert attention from domestic political problems.9 Morgan and Bickers, and DeRouen, among others, offer evidence that U.S. Presidents are prone to diversionary behavior when they face a decline in the support of one of the factions within their ruling coalition, such as the party.

Not all studies, however, have been equally promising in their findings. Contrary to the wisdom that presidents use force to boost their popularity at home, contending studies mainly point to regime type, institutional constraints and rationality of addressing the sources of domestic discontent, rather than trying to sweep the problems under the carpet by diversionary actions. Lian and Oneal, Miller, Meernik and Waterman, and Prins and Sprecher, for instance, maintain that there is little evidence to support the existence of a relationship between domestic political conditions and American foreign policy.10 Their findings lean toward the fact that presidents are less likely to appeal to the use of force at times of economic and political discontent at home. Presidents, already constrained by domestic problems, they argue, cannot afford further erosion in their popularity by engaging in behaviors that carry with them the risk of failure.

In another debate, scholars investigate how strategic interaction influences the behavior of leaders, especially the behavior of potential targets of diversionary aggression.11 According to this line of inquiry, the willingness on the part of state leaders experiencing domestic problems to divert is not a sufficient condition for diversion to take place. Despite the fact that such leaders may be willing to engage in a diversionary behavior, it is perfectly reasonable to expect potential adversaries to anticipate this willingness and either limit their interactions with those leaders or respond cooperatively to avoid being the target of diversion.

The empirical findings, however, are too mixed to conclude that potential scapegoats engage in strategic conflict avoidance. DeRouen and Sprecher, for instance, observe that the Arab rivals of Israel use domestic unrest in Israel as an opportunity to escalate their hostility toward the latter rather than minimizing their interaction with the potential diverter.12 Fordham, on the other hand, analyzes the behavior of a sample of potential targets of diversion for American presidents from the list of enduring rivals of the U.S. identified by Diehl and Goertz.13 Fordham’s findings provide only qualified support to the strategic conflict avoidance thesis.14 Therefore, he warns us to be cautious not to expect too much from strategic conflict avoidance especially with countries such as Iran, Iraq and China, which use conflict with the U.S. as a way to enhance their legitimacy at home and prestige abroad.

The U.S. and Iran rivalry is a proto rivalry that starts with the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979

Diversion against Rivals

It is important to note that rivalry research program does not consider the conflict between rivals as a function of domestic processes. Instead, it concentrates on the temporal connection between the disputes of the same set of states and the history they create for each other.15 The central tenet of the research program is that conflict in one period influences conflicts in subsequent periods. It assumes that an initiated conflict left unresolved opens the path for a relationship of recurrent disputes between the same states.16 Thus, irrespective of domestic influences, the recurring conflict between rivals is considered to be a consequence of past conflicts.

Against this backdrop, investigation of diversionary tendencies among rivals shows that conflict between rivals is not entirely a consequence of their conflict history and may have some domestic antecedents.17 Sprecher and DeRouen (2005), in their analysis of conflict behavior between Israel and three Arab countries, Syria, Egypt and Jordan, find evidence that supports the link between domestic unrest and the level of hostility between the Middle Eastern rivals.18 Bennett and Nordstrom, on the other hand, focus uniquely on the influence of bad economy on the termination of conflict between 63 interstate dyads for the period of 1816-1992. Contrary to their expectation, they find a positive relation between declining economic conditions and aggressive behavior.19

Theoretically speaking, it sounds reasonable to expect rival states to use their rivalry for diversionary purposes. In the first place, a rivalry not only creates a permanent threat environment, without having to revert to major wars, but also creates and reinforces an enemy image for the public. Therefore, in difficult times, instead of choosing a random target, political leaders, who want to divert attention away from domestic problems, would be better off confronting a rival.20 Aggressive behavior against a state whose enmity has already been confirmed is easy to rationalize.21 The enemy image in the repertoire of the public makes the hostile action more credible and more readily justifiable and supportable. Thus, if the diversionary theory suggests that in-group cohesion is established with the existence of an enemy, the best target would be a country that already deserves that status.

Second, contrary to some arguments that require diversion to entail some risk involving action taken on the part of the sender, the initiation of a conflict with diversion in mind does not necessarily require recourse to actions that can lead to escalation.22 State leaders can create the perception of a foreign threat employing less risky tactics such as threats to use force, shows of force, and use of force short of war.23 Indeed, since the goal does not involve the achievement of some high-value issues at stake, it does not make sense for diverting leaders to risk a conflict that can escalate into war.After all, what gives the theory its clout is not that a government is willing to go to war but that conflict is utilized to decrease domestic conflict by unifying the society against the external threat. Not being an end in itself, this type of external conflict, therefore, should be carefully crafted to prevent the costs exceeding the benefits.24

To keep the spirit of revolution alive, the Iranian elite presents the regime as a continued uprising against the forces such as western imperialism and Zionism that once sustained the U.S. presence in Iran

Again, rivals make a better target if the intention is to initiate a relatively “cheap and manageable incident to divert attention without imposing a major cost.” As noted by Bennett and Nordstrom, “over the course of many confrontations, rival states may learn to anticipate response patterns, leading to safer disputes or at least to leaders believing that they can control the risks of the conflict when they initiate a new confrontation.”25

If rivals make good scapegoats is it possible to say that leaders of the U.S. and Iran, drawing lessons from previous interactions that a confrontation with an adversary has cohesive effects on the public, are encouraged to resort to a similar type of behavior with an already acknowledged enemy to achieve similar effects on the public? In other words, do Americans and Iranians demonize each other for domestic political purposes? Although in an earlier investigation, Davies probes a similar question, his focus is nevertheless exclusively on the Iran side of the equation.26 More specifically, he examines whether Iranian aggression towards the U.S. is influenced by internal difficulties of the regime. In addition to providing results that are consistent with diversionary hypothesis, Davies also produce evidence indicating that Iran engages in strategic conflict avoidance. However, Davies’ findings are one-sided and only provide a partial picture of the rivalry between the U.S. and Iran. Therefore, it is important to account for this gap.

Domestic Determinants of the U.S.-Iran Rivalry

A good place to start probing the chance of diversion within the U.S.-Iran rivalry is to determine what kind of a rivalry the pair constitutes. Although there are different conceptualizations and operationalizations of rivalry because of the ease with which to determine which states are rival and which states are not, Klien, Goertz and Diehl’s “enduring rivals” classification is more commonly utilized.27 According to this classification, “rivalries consist of the same pair of states competing with each other, and the expectation of a future conflict relationship is one that is specific as to whom the opponent will be.”28 Based on this definition, Klien et al. identify two different forms of rivalry: enduring (long-term rivalries) and proto rivalries (short-term rivalries). Enduring rivalries, as a rule, refer to those rivalries that have experienced at least six disputes within a 20-year time frame. Proto rivalries, on the other hand, experience more than two disputes but do not satisfy the condition of duration.29

The U.S. and Iran rivalry is a proto rivalry that starts with the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979, which replaced the pro-U.S. autocratic regime of Shah Riza Pahlavi with the theocratic regime led by the supreme leader of the revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini. Although they never came into a direct confrontation, both sides accused each other for decades. The U.S., for instance, portrayed Iran as a regime dedicated to overthrowing the regional status quo, committed to supporting terrorism, and promoting animosity toward Israel. Iran, on the other hand, has constantly accused the former of supporting anti-regime groups, supporting Iraq’s invasion of Iran in 1980, and crippling Iran’s economy by systematic sanctions.30

Klein et al. record the rivalry between the U.S. and Iran to have ended in October 1997.31 The scope of their data, however, terminates in 2001. Therefore, it does not take into account developments subsequent to 2001. A closer look at U.S.-Iran relations reveals that, despite a short span of rapprochement between Iran and the U.S. with the election of moderate Iranian president Mohammed Khatami to power in May 1997, the relations reverted to their conflictual course as the Bush Administration declared Iran one of the “rough states.”32 Along with the continuation of economic sanctions on Iran, the U.S. initiated a campaign with major European allies against Iran’s nuclear program and further deepened Iran’s isolation from the international community.33

The common view held among experts is that strategic calculations and a policy guided by pragmatism dictate the course rivalry between the U.S. and Iran. This is especially true for the period after the death of the supreme leader of the Iranian Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, when there was a visible shift in Iranian policy toward moderation designed to end the isolation of Iran from the rest of the international community.34

Nevertheless, the same scholars also acknowledge the influence of the ideological and domestic issues as conditioning factors in front of rapprochement between the U.S. and Iran.35 One scholar, for instance, maintains that in Iran ideology prevails over national interest in their foreign policy formation because it serves the demand and needs of domestic constituencies.36 The Iranian leadership, according to Vakil, uses ideology as a tool to capture support from their domestic audiences.37

Approaching the issue from the perspective of the political discourse, Beeman observes that the mindset of the Iranian elite is built on the concept of resistance. In this view, since the beginning of the revolution, Iranians have taken resistance to external forces as the sole mean of not only establishing and maintaining revolutionary credentials and a correct moral posture on the international scene, but also promoting religious purity.38 Thus, for Iranian policymakers compromise with the U.S. is equal to the betrayal of revolutionary ideals.

This tug of war in Iranian politics when coupled with a growing population dissatisfied with the state of the economy brings into mind the possibility that those who are in charge in Iran use conflict with the U.S. as a tool to enhance the regime’s stability

When one interprets this ideological posture in the light of economic and socio-political challenges facing Iran, it is reasonable to expect the political elites to revoke symbolic confrontations that will serve to underscore the stability of the regime. According to the observers of Iran, the country suffers badly from economic problems.39 High inflation rates, unemployment, underemployment, and declining standards of living have alienated the majority of the population and extinguished the passions of revolution. While these problems are being exacerbated by a rapidly growing population rate, the economy is not the only sector that suffers from demographic pressures. For the new generation of young people, a revolution is merely an event that remains in the past. Not only do young people lack the ideals of the revolution, they are also more favorable and penetrable to American influence.40 Thus, to keep the spirit of revolution alive, the Iranian elite presents the regime as a continued uprising against the forces such as western imperialism and Zionism that once sustained the U.S. presence in Iran.41

Furthermore, the issue of normalizing U.S.-Iran bilateral relations has become deeply entangled in Iran’s power struggle. It has been reported that the tug of war between the regime’s hardliners and reformists has held the relations with the U.S. hostage to domestic political stalemate and blocked any real progress.42 While reformists want to liberalize the country along political and economic lines, the hardliners, who control most of the unelected institutions of the regime, view political liberalization as a threat to their influence over the state apparatus and thus strongly oppose socio-cultural liberalization and the growth of western influence.43 The conservatives not only see improvement of relations with the U.S. as a threat to the achievements of the revolution, but are also concerned that normalization in relations with Washington will contribute to enormous popular credit to reformers and will prevent them from using “Great Satan” imagery to rally support and attack their opponents.44

It is not surprising, therefore, to see regime hardliners blaming the U.S. and the enemies of the regime for provoking instability in Iran. For instance, when violent measures taken by conservatives to obstruct the reform process provoked students to protests and demonstrations supporting political reforms and denouncing violence against reformers, conservatives were quick to blame the U.S. for instability to justify actions taken to defuse popular pressures for the reform.45

This tug of war in Iranian politics when coupled with a growing population dissatisfied with the state of the economy brings into mind the possibility that those who are in charge in Iran use the conflict with the U.S. as a tool to enhance the regime’s stability. To investigate this possibility, I construct the following two hypotheses that relate domestic political and economic developments in Iran to its external behavior toward the U.S.

H1: Domestic political unrest in the country increases the incentive of Iranian leaders to follow a hostile course toward the U.S.

H2: As the economic conditions in the country worsens, the Iranian leaders become more hostile toward the U.S.

However, as noted by Fordham, there is also the possibility that rather than having to provoke any confrontation, Iran is just responding to the U.S. to enhance its legitimacy and prestige. Indeed, many observers of the relations between these two countries maintain that U.S. sanctions against Iran proved counterproductive and caused more defiance in the Iranian leadership.46 Vakil, for instance, states that the “siege” mentality of Iranian policymakers, which is considered to be a consequence of the regime’s isolation from the rest of the international community, induces them to respond to American challenges in kind. This is exactly what happened when the Bush Administration classified Iran as a “rough regime.”47 According to Vakil, aggressive American policy not only reinforced the threat perception from the U.S., but also enabled the hardliners of the regime to reassert their control at home. Therefore, instead of adopting conciliatory behavior to evade hostility from the U.S., the Iranian policymakers should treat hostile behaviors coming from the U.S. as an opportunity to exploit. By this account, Iran should not engage in any strategic conflict avoidance but instead reciprocate the hostility from the U.S. in kind and manner. The following hypotheses are derived to test strategic conflict avoidance behavior of Iran.

H3: Iran’s behavior does not become conciliatory when there is a decline in the U.S. presidential approval ratings or increase in inflation rates.

H4: Iran’s behavior toward the U.S. becomes hostile as it faces hostility from the latter.

Iranian women carrying placards during a demonstration outside the former U.S. embassy in Tehran on November 4, 2017, marking the anniversary of its storming by student protesters. | ATTA KENARE / AFP / Getty Image

While these are potential causes that might explain Iranian hostility toward the U.S., there is also the other side of the relation that needs to be explained: does the U.S. use conflict with Iran for diversionary purposes? Several studies investigating diversionary tendencies of U.S. Presidents have found results that support the diversionary hypothesis. Many scholars report a direct link between domestic conditions such as elections, unemployment, inflation and presidential popularity and the use of force abroad.48 This still, however, begs the question: why the U.S. would divert specifically against Iran?

As noted earlier, the public perception of Iran as a hostile regime to the U.S. and its interests makes Iran a readily available scapegoat for U.S. Presidents. Beeman, for instance, observes that since 1978 it is universal to be hostile toward Iran. Like Iranian leaders, the U.S. Presidents use the vilification of Iran “as a political stratagem for domestic political purposes.”49 The most recent reinforcement of the “mad mullah” image of Iran in the American public mind, according to Beeman, was advanced by the Bush Administration. Beeman observes that because Iran was already demonized in the public mind, the administration was blaming Iran for everything in the hope that any accusation against it would be treated as fact and would help rouse the American electorate and provide another demonstration of President Bush’s resolve to resist evil in the world. Evidence from public opinion polls show that the general public has been receptive to portrayals of Iran as a menace to be eradicated.50

Along similar lines, Bill emphasizes the influence of the strong Israeli lobby in the U.S. and maintains that despite the fact that the Bush Administration, in its early days in office, had the tendency to improve relations with the Iranian regime, the strong Israeli lobby in Congress had prevented the new administration to follow such a course of relations.51

Therefore, to see whether the U.S. hostility toward Iran is actually influenced by diversionary incentives, I test the following hypotheses.

H5: Negative change in presidential job approval ratings, increase the tendency of the U.S. Presidents to be more hostile toward Iran.

H6: Increasing economic problems in the U.S., negatively influence the behavior of the U.S. Presidents toward Iran.

Research Design

I test the following models to uncover whether the actions of Iran and the U.S. are influenced by domestic factors.

Iran’s behavior toward the U.S.: Domestic unrest in Iran + Iran inflation + U.S. hostility + third-party relations with Iran + U.S. monthly approval ratings + U.S. inflation.

US behavior toward Iran: Monthly approval ratings + U.S. inflation + Iran’s behavior + third-party relations with Iran.

The dependent variable in each model is the level of conflictual and cooperative actions directed by the sender against the target. This variable is aggregated into monthly time intervals to get a summary measure of conflict and cooperation. To capture the level of conflict or cooperation directed by the U.S. against Iran and vice versa, I use Integrated Data for Event Analysis (IDEA), which covers the period 1990-2004.52

Iran does not become defiant toward the U.S. as its relations with third parties improve. How the U.S. treats Iran has a strong effect on the attitude of Iran toward the U.S.

IDEA is constructed from daily newspaper reports coded into categories of cooperation and conflict by ordering events according to their intensity, from the most peaceful event to the most war-like. The events are coded by automated computer software that reads Reuters Business Briefing newswire and converts them into programmed categories. The events in IDEA are coded according to a scale of 22 major cue categories (01 to 22), and their subcategories represented by extra digits, along with a continuum of cooperation and conflict that occurs between the actors. Idea codes 01, 08, 17, 22, for instance, stand for yield, agree, threaten and use of force, respectively. These conflict and cooperation categories can be converted into weights along a continuum of -10 to +10 developed by Goldstein that makes it possible to get a score of conflict or cooperation by aggregating them into monthly time intervals.53

In order to capture domestic conditions that might lead to diversionary actions, I test a number of factors that are widely investigated by other scholars studying diversionary theory. To portray domestic conditions in Iran, I use domestic political unrest and changes in inflation as factors that might condition the behavior of policymakers in adopting a more conflictual or cooperative stance toward the U.S. As with the external behavior of Iran, the measure of domestic political unrest for this country is constructed from IDEA. I included in the aggregation only those events that scored below -5 on the Goldstein scale. The data for inflation are monthly percentage changes in consumer prices gathered from the International Monetary Fund website.

As for the U.S., I employ two variables: monthly presidential approval ratings and monthly percentage changes in inflation rates. The first variable, monthly presidential approval ratings, is calculated from opinion polls provided by the Roper Center regarding U.S. Presidents’ job approval ratings as reported by different organizations. These polls are aggregated to create monthly approval ratings for each president that has been in office since 1990. Data on inflation are gathered from the International Monetary Fund website.54

Domestic factors are only one possible influence on the behavior of the U.S. and Iran toward each other. Failing to account for the influence of reciprocation as well as the influence of international factors that also effect rivals’ behavior toward each other could produce misleading inferences. In the first place, it is perfectly reasonable to expect that the U.S. and Iran are reciprocating each other’s actions rather than their behavior being influenced by domestic processes. To account for this possibility, I include in each model the impact of the level of conflict and cooperation that each state directs toward the other.

An equally relevant concern to be taken into consideration is the improving relations of Iran with third parties. Since the U.S. wants to keep Iran isolated, it is reasonable to expect U.S. policymakers to be hostile toward Iran to scare away third parties that are willing to improve their relations with that country. On the other side of the coin is the possibility that improving relations with other countries might give the Iranians a sense of esteem and recovery from isolation and encourage them to adopt a more defiant and firmer stance against the U.S. Thus, it is important to take into account how Iranian relations with third parties condition the behavior of Iran and the U.S. To control for these possibilities, I create a variable using IDEA data that measures the overall cooperative relations of Iran with the following countries: France, Germany, Russia and China. These countries are selected for their influence within the United Nations and/or the European Union. This variable is included in both models to see how Iran and the U.S. react to Iranian relations with third parties.

Despite their commitment to revolution, Iranian leaders calculate that the only way to sustain the support of their constituencies is to improve their economic conditions and not to confront the U.S.

Finally, Fordham suggests that strategic conflict avoidance behavior should be included in the models of potential targets of the U.S. to better reach conclusions of the diversionary tendencies of American leaders.55 To test whether Iranian leaders behave strategically to avoid being the target of a possible diversionary action, I include in the model, which tests the conflict-cooperation behavior of Iran, the U.S. presidential approval ratings and monthly percentage change of inflation in the U.S. If the strategic conflict avoidance thesis is correct then these variables should be related to Iranian conflict and cooperation behavior toward the U.S.

Results and Discussion

In this section, I discuss the empirical results of the models in the preceding section. The data are estimated using a two-stage least squares method. Two variables, U.S. behavior and Iran behavior are used simultaneously in both models as independent and dependent variables. This creates an endogeneity problem because the dependent variable in one equation is used as an explanatory variable in the other equation without accounting for its causal factors. Under this condition, using the ordinary least squares method is likely to produce biased and inconsistent coefficients. However, using two-stage least squares method, it is possible to correct for this problem and obtain consistent estimates. The procedure takes into account the indirect influences that cause endogeneity.

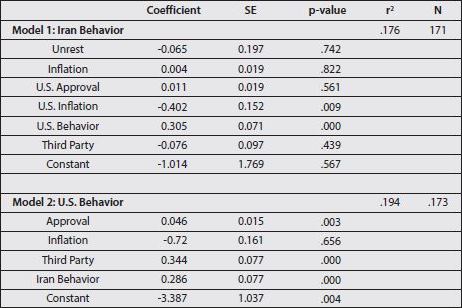

Table 1 presents the results of models constructed above. Both models include indices of conflict and cooperation derived from IDEA data. The first model incorporates domestic as well as external indicators that estimate Iranian behavior toward the U.S. Domestic unrest and inflation rates are employed to capture domestic conditions in Iran. U.S. presidential approval ratings and inflation rates test whether Iran behaves strategically to avoid becoming the target of a diversion when things go bad for U.S. Presidents. The model also controls for the Iranian response to U.S. behavior as well as the influence of cooperation with third parties on the behavior of Iran toward the U.S.

Table 1: Two-Stage Least Square Regression: The Influences of U.S.-Iran Behavior

Although the common practice among scholars is to lag independent variables by one month to capture the time elapsed between the dependent and independent variable, the approach taken here deviates from that practice. I leave these variables unlagged based on the logic that states do not wait one month to respond to each other.56 A final note is on interpolation. The following variables are interpolated to account for missing values: U.S. behavior toward Iran, Iran’s behavior toward the U.S., Iran’s domestic unrest, and third-party relations with Iran.Returning to the results, the findings presented in the first model illustrate no indication that Iran externalizes its domestic conflict. Both indicators of domestic discontent, inflation rates and unrest, are statistically insignificant. Likewise, Iranian actions toward the U.S. do not seem to be influenced by its relations with third parties. In other words, Iran does not become defiant toward the U.S. as its relations with third parties improve. However, how the U.S. treats Iran has a strong effect on the attitude of Iran toward the U.S. The control variable, U.S. behavior, shows that the only time Iran becomes hostile toward the U.S. is when it faces similar actions from it. This variable is statistically significant at p< .000 level.

These findings can be interpreted in two ways. In the first place, contrary to the argument devised above, domestic or ideological concerns do not appear to influence Iranian behavior toward the U.S. Perhaps, as observed by experts of U.S.-Iranian relations, despite their commitment to revolution, Iranian leaders calculate that the only way to sustain the support of their constituencies is to improve their economic conditions and not to confront the U.S. It is noted that the only way to satisfy the demands of the Iranians is to end Iran’s isolationism and open the country to international markets, a measure which requires improving relations with the U.S.57

U.S. Presidents actually become more hostile toward Iran as they experience a decline in their approval ratings

At the same time, however, one can argue that it is reasonable to expect a middle power like Iran to refrain from using diversion at least against a country such as the U.S. Fordham and others maintain diversion as a privilege of great powers like the U.S., which have the luxury of exercising influence on a global scale without risking any threat to their core national interests.58 From this perspective then, diversion for a country like Iran would be fraught with peril.59

But how does one explain Iranian reciprocation to U.S. hostility? Is Iran’s hostility a normal condition to observe in a rivalry setting or is it reasonable to assume that although Iran does not externalize its domestic problems, it finds retaliation to U.S. actions as a good opportunity to enhance its domestic legitimacy and international prestige? It is possible, as maintained by Fordham, that Iranian leaders find it difficult to exercise restraint not to reciprocate U.S. actions under domestic and international pressures.60 However, the latter possibility is not unwarranted if it is recalled that Iranian leadership views resistance to the U.S. as a means of maintaining revolutionary credentials and correct moral posture on the international scene. Thus, it is possible to draw the conclusion that despite the pragmatism carried by the regime’s elite, retaliation rather than compromise is viewed as the right course of action.

There is also the possibility that hostility from the U.S. at least helps hardliners to suppress the reform efforts and solidify their rule at home, as argued by the observers of U.S.-Iran relations. If it is correct that Iranian hardliners view improvement of relations with the U.S. as a threat to not only the achievements of the revolution but also their position within the regime, they should readily welcome hostility from the U.S. as an opportunity to restore their control.

Although one cannot reach this conclusion with certainty, that the findings do not offer any evidence to support the assumption of strategic conflict avoidance are clear from the results of the second model. While the U.S. presidential approval ratings do not seem to have any implications for Iran, U.S. inflation rates appear to have an effect on Iranian behavior, but not in line with the predictions of the strategic conflict avoidance hypothesis. The sign of the relation is negative, which implies that Iranians adopt a more hostile course as inflation rates of the U.S. increase. In other words, Iranians are not concerned with the possibility that they might become the target of a potential diversion. Instead, their behavior appears more confirmatory of the opportunity exploitation hypothesis.61According to the predictions of the opportunity exploitation model, domestic problems in the rival state, rather than dissuading the potential scapegoat from any provocative actions to avoid becoming the target of a diversion, create an incentive for the scapegoat to exploit the situation. Thus, it is possible to conclude that Iranian leaders tend to choose conflict with the U.S., perhaps, at times when U.S. Presidents are overwhelmed by economic problems at home.

The second model shows the determinants of U.S. behavior toward Iran. It includes two indicators of U.S. domestic conditions, the presidential approval ratings and inflation rates. The model also tests how U.S. behavior is influenced by the actions of Iran as well as the relations of Iran with prominent third parties.

The results in the second model confirm theoretical expectations that U.S. Presidents actually become more hostile toward Iran as they experience a decline in their approval ratings. The sign of the relation is positive. Given the fact that hostile actions are represented by negative signs, the positive sign between the approval ratings and U.S. behavior toward Iran is in line with the findings of earlier research that suggests a link between approval ratings and the initiation of dispute abroad. However, the same conclusions cannot be drawn for the link between bad economic conditions and hostility toward Iran. There is no evidence to support the hypothesis that U.S. Presidents become hostile toward Iran as inflation rates go up.

One cannot rule out the possibility that although Iran does not externalize its domestic conflict, it views reciprocation to U.S. aggression as an opportunity to enhance its legitimacy and prestige

The remaining two variables in the model, on the other hand, prove statistically significant. The parameter estimate for Iran’s behavior is highly significant. This result suggests that similar to Iran, the U.S. does not hesitate in retaliating against Iran in kind and manner. Likewise, the third-party variable also proves robust in the model. This finding contradicts the expectation that the U.S. becomes more conflictual with Iran to enhance its isolation by scaring away third parties that are willing to improve relations with Iran. According to this finding, U.S. relations with Iran improve as there is an improvement of Iran’s relations with third parties. However, it might be the case that the third parties improve their relations with Iran as they observe an improvement in U.S. relations with that country.

A group of Iranian Americans gathered in New York to voice support for the recent Iranian demonstrations. | MICHAEL BROCHSTEIN Getty Images

Conclusion

The recent studies of diversionary theory concentrate on two research questions. While some scholars extend the research to investigate domestic determinants of conflict between interstate rivals, others highlight the need to account for the strategic conflict avoidance of potential targets. In this paper, I have addressed both issues by analyzing the conflict between the U.S. and Iran between 1990 and 2004. My concern, in the first place, has been to uncover whether the proto rivalry between the U.S. and Iran is influenced by domestic political and economic factors. Furthermore, to reach a more thorough conclusion, especially regarding U.S. diversionary tendencies, I have investigated whether Iran behaves strategically to avoid being the target of a U.S. diversion.

The results provide mixed support to the argument that rival states use their rivalry for diversionary purposes. While the empirical findings in line with earlier studies confirm the diversionary tendencies of the U.S., the same conclusions cannot be drawn for Iran’s actions toward the U.S. Iran’s behavior against the U.S. does not appear to be influenced by political and economic indicators of domestic discontent. The research also finds no indication that Iran’s behavior fits the strategic conflict avoidance model.

The only time Iran appears to be hostile toward the U.S. is when it faces a similar type of behavior from the latter. The fact that Iran responds to U.S. action can be considered as the expected course of action in a rivalry setting. However, at the same time, one cannot rule out the possibility that although Iran does not externalize its domestic conflict, it views reciprocation to U.S. aggression as an opportunity to enhance its legitimacy and prestige.

In light of these findings, future research examining the domestic determinants of Iran’s behavior toward the U.S. can benefit from the addition of two factors that have not been addressed here. In the first place, I should acknowledge that my measures of domestic discontent might not have captured the true nature of domestic unrest in Iran. A more refined model that distinguishes the conflict between hardliners and reformers should be established to reach better conclusions. Second, given the dependence of the Iranian economy on oil exports, oil prices in international markets should be incorporated in future studies of the domestic determinants of Iranian behavior toward the U.S. As for the U.S. side of the equation, along with unemployment rates, future research should take into account the influence of actions directed by Iran toward Israel.

Endnotes

1. Jack S. Levy, “Diversionary Theory of War,” in Manus I. Midlarsky (ed.), Handbook of War Studies, (Boston: Unwin Hyman, Inc., 1989); Jack S. Levy, “The Causes of War and the Conditions of Peace,” Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 1, (1998), pp. 139-165; Jonathan W. Keller and Dennis M. Foster, “Don’t Tread on Me: Constraint-Challenging Presidents and Strategic Conflict Avoidance,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 4 (2016), pp. 808-827.

2. Benjamin Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance and the Diversionary Use of Force,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 67, No. 1 (February 2005), pp. 132-153.

3. “Iran: The Struggle For the Revolution’s Soul,” International Crisis Group, ICG Middle East Report, No. 5, (August 2012); Keith Crane, Rollie Lal, and Jeffrey Martini, “Iran’s Political, Demographic, and Economic Vulnerabilities,” RAND Institute, retrieved from https://www.rand.org/content/

4. Maximilian Terhalle, “Revolutionary Power and Socialization: Explaining the Persistence of Revolutionary Zeal in Iran’s Foreign Policy,” Security Studies, Vol. 18, (2009), pp. 557-586; Sanam Vakil, “Between Ideology and the National Interest: An Analysis of US-Iranian Relations from 1989-2002,” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 2005; Ray Takeyh, “Iranian Options: Pragmatic Mullah’s and America’s Interests,” National Interest, Vol. 73, No. 3 (2003), pp. 49-56.

5. Uriel Abulof, “Nuclear Diversion and Legitimacy Crisis: The Case of Iran,” Politics and Policy, Vol. 41, No. 5 (2013), pp. 690-722.

6. Vakil, “Between Ideology and the National Interest.”

7. D. Scott Bennett and Timothy Nordstrom, “Foreign Policy Substitutability and Internal Economic Problems in Enduring Rivals,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 44, No. 1 (2000), pp. 33-61; Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance and the Diversionary Use of Force”; Christopher Sprecher and Karl DeRouen, “Domestic Determinants of Foreign Policy Behavior in Middle Eastern Enduring Rivals, 1948-1998,” Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 1, (2005), pp. 121-141.

8. Levy, “Diversionary Theory of War”; Levy, “The Causes of War and the Conditions of Peace.”

9. Charles W. Ostrom and Brian Job, “The President and the Political Use of Force,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 80, No. 2 (1986), pp. 541-546; Bruce Russet, “Economic Decline, Electoral Pressure, and the Initiation of Interstate Conflict,” in C. Gochman and A. N. Sabrosky (eds.), Prisoners of War? Nation States in the Modern Era, (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1990); T. Clifton Morgan and Kenneth N. Bickers, “Domestic Discontent and the External Use of Force,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 36, No. 1 (1992), pp. 25-52; Christopher Gelpi, “Democratic Diversions: Governmental Structure and the Externalization of Domestic Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 41, No. 2 (1997), pp. 255-282; T. Clifton Morgan and Christopher J. Anderson, “Domestic Support and Diversionary External Conflict in Great Britain, 1950-1992,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 61, No. 3 (1999), pp. 799-814; Kurt Dassel and Eric Reinhardt, “Domestic Strife and the Initiation of Violence at Home and Abroad,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 43, No. 1 (1999), pp. 56-85; Dennis M. Foster, “Inter Arma Silent Leges? Democracy, Domestic Terrorism, and Diversion,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, (2015); Kristian S. Gleditsch, Idean Saleyhan, and Kenneth Schultz, “Fighting at Home, Fighting Abroad: How Civil Wars Lead to Interstate Disputes,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 52, (2008), pp. 479-506; Kurt Dassel, “Civilians, Soldiers, and Strife: Domestic Sources of International Aggression,” International Security, Vol. 23, No. 1 (1998), pp. 107-140; Karl R. DeRouen Jr., “The Indirect Link: Politics, the Economy, and the Use of Force,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 39, No. 4 (1995), pp. 671-695.

10. Bradley Lian and John R. Oneal, “Presidents, the Use of Military Force, and Public Opinion,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 37, No. 2 (1993), pp. 277-300; James Meernik and Peter Waterman, “The Myth of the Diversionary Use of Force by American Presidents,” Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 3 (1996), pp. 573-590; Ross A. Miller, “Domestic Structures and the Diversionary Use of Force,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 39, No. 3 (1995), pp. 760-785; Brandon C. Prins and Christopher Sprecher, “Institutional Constraints, Political Opposition, and Interstate Dispute Escalation: Evidence from Parliamentary Systems,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 36, No. 2 (1999), pp. 271-287.

11. Alastair Smith, “International Crises and Domestic Politics,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No. 3 (1996), pp. 623-638; Ross A. Miller, “Regime Type, Strategic Interaction, and the Diversionary Use of Force,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 43, No. 3 (1999), pp. 388-402; David H. Clark, “Can Strategic Interaction Divert Diversionary Behavior? A Model of U.S. Conflict Propensity,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 65, No. 4 (2003), pp. 1013-1039; Karl Derouen and Christopher Sprecher, “Arab Behavior towards Israel: Strategic Avoidance or Exploiting Opportunities?,” British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 36, (2006), pp. 549-560; Fordham “Strategic Conflict Avoidance.”

12. DeRouen and Sprecher, “Arab Behavior towards Israel.”

13. Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance”; Paul Diehl and Gary Goertz, War and Peace in International Rivalry, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

14. Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance.”

15. Diehl and Goertz, War and Peace in International Rivalry; John Vasquez and Christopher Leskiw, “The Origin and War Proneness of Interstate Rivals,” Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 4, (2001), pp. 295-316. William R. Thompson, “Identifying Rivals and Rivalries in World Politics,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 4 (2001), pp. 557-586. Michael Colaresi and William Thompson, “Strategic Rivalries, Protracted Conflict, and Crisis Escalation,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 39, No. 3 (2002), pp. 263-287.

16. D. Scott Bennett, “Security, Bargaining, and the End of Interstate Rivalry,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 40, (1996), pp. 157-184.

17. Sara McLaughlin Mitchell and Brandon C. Prins, “Rivalry and Diversionary Uses of Force,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 48, (2004), pp. 937-961.

18. Sprecher and DeRouen, “Domestic Determinants of Foreign Policy Behavior.”

19. Bennet and Nordstrom, “Foreign Policy Substitutability.”

20. Kyle Haynes, “Diversionary Conflict: Demonizing Enemies or Demonstrating Competence?,” Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol. 34, No. 4 (2017), pp. 337-358.

21. Sung Chul Jung, “Foreign Targets and Diversionary Conflict,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 58 (2014), pp. 588-578.

22. Ahmer Tarar, “Diversionary Incentives and the Bargaining Approach to War,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (2006), pp. 169-188.

23. Erin Baggott, “Diversionary Cheap Talks: Domestic Discontent and U.S. Foreign Policy, 1945-2006,” International Studies Association Conference, Toronto, (March 28, 2014).

24. Richards, et al., “Good Times, Bad Times,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 37, No. 3 (1993), pp. 504-535.

25. Bennett and Nordstrom, “Foreign Policy Substitutability,” p. 39.

26. Graeme A. M. Davies, “Inside Out or Outside In: Domestic and International Factors Affecting Iranian Foreign Policy Towards the United States 1990-2004,” Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 4, (2008), pp. 209-225.

27. James P. Klein, Gary Goertz and Paul F. Diehl, “The New Rivalry Dataset: Procedures and Patterns,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 43, No. 3 (2006), pp. 331-348.

28. Klein et al., “The New Rivalry Dataset: Procedures and Patterns,” p. 303.

29. Diehl and Goertz, War and Peace in International Rivalry.

30. James A. Bill, “The Politics of Hegemony: The United States and Iran,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2001), pp. 89-100; Vakil, “Between Ideology and the National Interest.”

31. Klein et al., “The New Rivalry Dataset.”

32. Simon Dalby, “Geopolitics, the Revolution in Military Affairs and the Bush Doctrine,” International Politics, Vol. 46, No. 2 (2009), pp. 234-240.

33. Philip Giraldi, “No Way Out: Washington’s Iran Policy Options,” Mediterranean Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 2 (2011), pp. 1-10.

34. Vakil,“Between Ideology and the National Interest”; Takeyh, “Iranian Options”; Ray Takeyh and Nikolas S. Gvosdev “Pragmatism in the Midst of Iranian Turmoil,” Washington Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 4 (2004), pp. 33-56; Enayatollah Yazdani and Rizwan Hussain, “United States’ Policy towards Iran after the Islamic Revolution: An Iranian Perspective,” International Studies, Vol. 43, No. 3 (2006), pp. 267-289; Kenneth Pollack and Ray Takeyh, “Taking on Tehran,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 84, No. 2 (2005), pp. 20-34.

35. Eva Patricia Rakel, “Iranian Foreign Policy since the Islamic Revolution: 1979-2006,” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, Vol. 6, (2007), pp. 161-163.

36. Terhalle, “Revolutionary Power and Socialization.”

37. Vakil, “Between Ideology and the National Interest.”

38. William O. Beeman, The Great Satan vs. the Mad Mullah: How the United States and Iran Demonize Each Other, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); Terhalle, “Revolutionary Power and Socialization.”

39. Mark J. Gasiorowski, “The Power Struggle in Iran,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 7, No. 4 (2000), pp. 22-40; Takeyh, “Iranian Options”; Takeyh and Gvosdev, “Pragmatism in the Midst of Iranian Turmoil”; Pollack and Takeyh, “Taking on Tehran”; Michael Rubin and Patrick Clawson, “Patterns of Discontent: Will History Repeat in Iran?,” Middle East Review of International Affairs, Vol. 10, No. 1(2006), pp. 105-121.

40. Takeyh, “Iranian Options”; Patrick Clawson, “The Paradox of Anti-Americanism in Iran,” Middle East Review of International Affairs, Vol. 8, No. 1(2004), pp. 16-24.

41. Pollack and Takeyh, “Taking on Tehran.”

42. Gasiorowski, “The Power Struggle in Iran.”

43. Gasiorowski, “The Power Struggle in Iran.”

44. Gasiorowski, “The Power Struggle in Iran”; Takeyh, “Iranian Options”; Takeyh and Gvosdev, “Pragmatism in the Midst of Iranian Turmoil.”

45. Gasiorowski, “The Power Struggle in Iran.”

46. Takeyh and Gvosdev, “Pragmatism in the Midst of Iranian Turmoil”; Yazdani and Hussain “United States’ Policy towards Iran after the Islamic Revolution.”

47. Vakil “Between Ideology and the National Interest.”

48. Ostrom and Job, “The President and the Political Use of Force”; DeRouen “The Indirect Link”; Benjamin Fordham, “The Politics of Threat Perception and the Use of Force: A Political Economy Model of U.S. Uses of Force, 1949-1994,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 42, (1998), pp. 567-590; Morgan and Bickers, “Domestic Discontent and the External Use of Force.”

49. Beeman, The Great Satan vs. the Mad Mullah.

50. Ido Oren, “Why Has the United States not Bombed Iran? The Domestic Politics of America’s Response to Iran’s Nuclear Program,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 24, No. 4, (2011), pp. 659-684.

51. Bill, “The Politics of Hegemony.”

52. Doug Bond, et al., “Integrated Data for Events Analysis (IDEA): An Event Typology for Automated Events Data Development,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 40, No. 6 (2003), pp. 733-745; Gary King and Will Lowe, “An Automated Information Extraction Tool for International Conflict Data with Performance as Good as Human Coders: A Rare Events Design,” International Organization, Vol. 57, (2003), pp. 617-642.

53. Joshua S. Goldstein, “A Conflict-Cooperation Scale for WEIS Events Data,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 36, No. 2 (1992), pp. 369-385.

54. “World Economic Outlook Databases,” International Monetary Fund.

55. Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance.”

56. King and Lowe, “An Automated Information Extraction Tool.”

57. Takey and Govesdev, “Pragmatism in the Midst of Iranian Turmoil.”

58. Levy, “Diversionary Theory of War”; Russett, “Economic Decline, Electoral Pressure, and the Initiation of Interstate Conflict.”

59. Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance.”

60. Fordham, “Strategic Conflict Avoidance.”

61. DeRouen and Sprecher, “Arab Behavior Towards Israel.”