While Turkish foreign policy has become increasingly active and assertive, it has recently confronted with a number of challenges in the Middle East, leading critics to claim that the AK Party government’s “zero problems with neighbors” vision has failed.2 In the meantime, however, Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans3 have displayed a completely different picture. During the last decade, Turkey has not only maintained, but also advanced its good neighborly relations with all countries in this region.

This article aims to provide a general overview of Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans during the AK Party government. It will argue that compared to the 1990s, diplomatic, economic, social, and cultural relations with this region have improved significantly, even though Turkey’s concerns and aims with respect to the region remained largely the same. This improvement was thanks to the convergence of a number of factors such as Turkey’s diplomatic activism, its better economic performance vis-à-vis other regional players, the strengthening of civil society and business sector in Turkey and the slowing down of the Europeanization of the Western Balkans. The improvement of relations has been most observable in economic and social terms, and from the late 2000s onwards, the Turkish government also expended considerable effort to convert it into political influence. However, in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, Turkey’s diplomatic engagement with the region has been in decline. While Turkey’s economic activity in the region is still increasing, the window of opportunity for a stronger political position may narrow in the future.

Turkey’s Western Balkans Policy since the 1990s

After the Cold War

Many aspects of Turkey’s Western Balkans policy have shown strong continuity since the end of the Cold War.4 Having remained virtually separated from the region by an iron curtain for almost half a century, Turkey has been endeavoring to (re-)establish itself in the Balkans for about two decades. As the dissolution of the Communist bloc and the emergence of new states brought about swift and radical changes in the international and regional systems and created new opportunities as well as challenges for Turkey, the policymakers in Ankara realized the necessity of developing a new outlook for approaching the region.5 Given the atmosphere of transition and uncertainty, Turkey felt an urgency to act pro-actively to forestall security threats, contribute to regional peace and stability and strengthen its social and economic bonds with the Balkans, among other surrounding regions.

During the last decade, Turkey has not only maintained, but also advanced its good neighborly relations with all countries in the Balkan region

In addition to geo-strategic concerns, economic and socio-cultural motivations6 drove the Turkish policymakers in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War to develop a new, more active, policy in the Balkans.7 Accordingly, Turkey offered its contribution to the security and welfare of the region by participating in security operations and, albeit sporadically, offering political initiatives for dialogue, concluded bilateral agreements, encouraged trade and provided technical, educational, and developmental assistance. However, these efforts did not bring about a rapid change in Turkey’s political and economic status in the Western Balkans. While the ensuing conflicts and tensions in the region prevented new venues and opportunities for international cooperation, political quarrels as well as economic crises in Turkey throughout the 1990s and early 2000s prevented this country from fulfilling its political, economic, and social potential in materializing its foreign political ambitions. In other words, neither the political circumstances in the Western Balkans nor its own political, economic, and social resources allowed Turkey to more actively engage with the region.

In terms of domestic, international, structural and agency-based factors, the early 2000s were a turning point for Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans. In the wake of the Kosovo War of 1999, the European Union launched the Stabilization and Association Process with the Western Balkans and at the Thessaloniki Summit of 2003 it offered the prospect of full integration. As all states in the region regard the accession to the EU as a strategic priority, the membership incentive has brought about a relatively peaceful atmosphere and led to steps for normalization of relations among states and communities. The increased stability has also enabled the Western Balkan governments to concentrate more on domestic reform, economic liberalization, and institutional consolidation. All this has created new opportunities for Turkey to become further involved in the region and expand its relations. The improvement of Turkish-Greek relations at the turn of the millennium ended their longstanding rivalry in the Western Balkans and induced them to relax their security-based approach and engage in the region on the basis of economic interdependence and soft power instead. Meanwhile, after a series of short-lived coalition governments, which lasted more than a decade, the coming to the power of the AK Party with the November 2002 elections opened a new era in Turkish domestic politics. During the AK Party government, political stability, economic growth, as well as structural and democratic reforms have provided Turkey with better resources and higher confidence in foreign policy. The changes in Turkey have also strengthened its civil society and the role of business actors, and these actors began to take an increasingly important part in Turkey’s external relations.

The AK Party’s Approach: New Concepts and Dynamism

Since its inception, the AK Party government has adopted Ahmet Davutoğlu’s8 ambitious framework for Turkish foreign policy, which involved an integrative and holistic utilization of the country’s geostrategic, social, cultural, and historical resources. Unsurprisingly, the Balkans is among the regions that Davutoğlu placed the greatest importance. In Stratejik Derinlik (Strategic Depth), he presents his prescriptions regarding Turkey’s Balkans policy mainly along three lines: first, he believes that in order to strengthen its influence over the region and maintain it both during peacetime and in case of tension or conflict, Turkey should primarily strengthen its relations with the elements connected to Turkey “with history and by heart” (read the Muslims) and bring the Ottoman-Turkish cultural heritage to the fore. Second, he regards Turkey’s geographical, social and economic resources that can connect the Balkans to other nearby basins as an invaluable asset. For him, acting as a pivotal state connecting the Balkans with the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia will not only contribute to peace and stability in these regions, but also increase Turkey’s diplomatic leverage. Third, Davutoğlu finds it essential that Turkey forestalls the involvement of other external powers in the Balkans by actively engaging in intra-regional politics and having closer relations with all relevant actors there.9

Having laid out in Stratejik Derinlik his geostrategic views regarding Turkey’s near abroad, Davutoğlu developed new ideas and concepts as he was actively involved in foreign policy making. As a general vision, he introduced the concept “zero problems with neighbors,” which in a nutshell aims to minimize conflicts and maximize trade and investment opportunities for Turkish businesses.10 The long-term objective of this is to develop a peaceful environment and a network of economic interdependence centered around Turkey.11 Obviously, this will also mean a central political position for Turkey, as any interdependence between Turkey and the smaller states around it would be an asymmetrical one, in which the vulnerability and sensitivity of the latter will be higher.12

For specifically the Western Balkans, Davutoğlu has defended two main principles, which have also been officially endorsed by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.13 The first one is regional ownership, which means that the problems of the region should be resolved by the participation and will of the indigenous actors. The aim of this is not only to check the political influence of external powers over the region, but also to disentangle the Western Balkans from the disagreements and rivalries among these powers, all of which have had a hand in the strife, tensions, and instability that have existed in the region for at least two centuries. The second principle is all-inclusiveness, i.e. taking into account all the views of the parties in an effort to settle the conflicts in the region. The idea behind this is that through dialogue regional actors can revise the existing arrangements that had been introduced and promoted by external actors in a more balanced outlook so as to satisfy the parties directly involved.

Although preceding governments had devised similar pro-active and integrative approaches for the Western Balkans, they were unable to carry them out systematically and vigorously due to the reasons mentioned before. With better political and economic resources and increased cooperation of the state with civil and business actors, the AK Party government was able to put them more effectively into practice. In addition, different from the general outlook of Turkey’s post-Cold War Balkans policy, Davutoğlu’s vision has involved an important element, that is the more active and institutional use of the common religion in approaching the Muslims in the region. Indeed, the existence of a sizable Muslim community with a shared Ottoman past has long been a strong, if not the strongest, factor shaping the interest of conservative members of the AK Party and its precursors in the Balkans.14 Considering the fostering of Islamic identity, particularly among the Bosniaks and Albanians, as a strategy that would facilitate and accelerate Turkey’s presence in the region, Davutoğlu complains in Stratejik Derinlik that secularist sensitivities and fears prevented Turkey from engaging in a stronger relationship with the Muslims in the Balkans and hence from utilizing a significant socio-cultural resource.15 Accordingly, during the AK Party period, state institutions have actively took part, either by themselves or in cooperation with the civil society, in matters like religious education and (re-)construction of mosques. The consolidation of Turkish-Islamic influence, as opposed to other Islamic currents, over the region on the one hand caused Arab-led Salafism, which grew popular during the 1990s, to decline16and on the other hand further strengthened social and cultural bonds between the local Muslim communities and Turkey. In the meantime, the Turkish government has also shown in various occasions that it was not intended to exclude the non-Muslims or to prop up one religious or ethnic community against another. Davutoğlu has expressed, on various occasions, that Turkey shared “strong historical, social, cultural and human ties” with all Balkan countries and emphasized multiculturalism.17 Turkish diplomats and bureaucrats in the region also underline their efforts for developing relations with Serbian, Montenegrin and Macedonian political actors and people.18

Under the AK Party government Turkish foreign policy involved an integrative and holistic utilization of the country’s geostrategic, social, cultural, and historical resources

Aspects of the Relations During the AK Party Government

During the 2000s, political dialogue, economic transactions and socio-cultural interactions between Turkey and the region increased gradually. Official visits, at both high and low levels, became more frequent than before, leading to a number of bilateral agreements for cooperation in commercial, economic, cultural, educational, industrial and technical matters, including free trade and visa exemption agreements.

Two developments around the year 2008 accelerated the upward trend in Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans. First, the global financial and economic crisis concerned the Western Balkan countries, all of which were in dire need for investments and cash inflows. For these countries, Turkey, whose economy remained relatively unharmed compared to many Western European and Mediterranean countries, became a serious alternative for economic partnership. Secondly, due to both the crisis and the lack of a swift progress in domestic reforms in the Western Balkans, the enthusiasm in the European Union for the integration of the region had been waning. In response, the Western Balkan countries started to look for other foreign policy options. Deepening political and economic relations with Turkey then became an expedient, and almost a necessary, foreign policy alternative. Even the government of Serbia, which had been cautious towards Turkey since the early 1990s, proposed a strategic partnership with Turkey in March 2009.

Facilitating Turkey’s “zero problems” policy in the Western Balkans, the requests for further cooperation, trade and investments gave Turkey the opportunity to translate economic interdependence into diplomatic leverage.19 In response, Turkey, which was also disillusioned with the lack of progress in the membership negotiations with the European Union, redoubled its efforts to increase not only its economic, cultural and social activity, but also political influence in the region.

Increased Diplomacy

Making the most of the opportunity of having the chairmanship-in-office of the SEECP for the years 2009-2010, Turkey offered mediation and dialogue for the resolution of inter-state and inter-communal disputes in the Western Balkans. The most fruitful of these attempts has been the trilateral consultation process among Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia. As the Dayton Peace Process and following initiatives by the USA and Europe did not yield any concrete results for a lasting understanding and peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkey took the initiative to bring Serbian and Bosnian political leadership together. At the first summit meeting of the trilateral mechanism, the presidents of the three countries signed a declaration underlining the territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the need for mutual dialogue and cooperation. During this process, Turkey found the middle ground between the two governments over the issue of the Srebrenica Massacre. While encouraging the Serbian government to apologize to the Bosnian Muslims for this catastrophic incident, Turkey also convinced the Bosnian government to accept the apology even though it did not employ the word “genocide.”20 This led to further steps for the normalization of diplomatic relations between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the Ankara summit in May 2013, the three states also agreed to establish a trilateral committee for the advancement of economic and commercial cooperation amongst each other.21

In the meantime, Turkey spearheaded a trilateral consultation mechanism with Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia22 and also worked for reconciling the parties on certain domestic issues in the Balkans, such as the dispute between two Islamic communities in Serbia for the official representation of the Muslims in the country23 and the government crisis in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2010-2011.24 While undertaking individual initiatives for mediation and reconciliation, Turkey has continued encouraging and actively participating in multinational institutions and missions operating in the Western Balkans.

Bosnian woman holds a poster of Prime Minister Erdoğan during an official visit to Sarajevo. / AA

Bosnian woman holds a poster of Prime Minister Erdoğan during an official visit to Sarajevo. / AA

To improve security, political stability, and economic prosperity of the region, Turkey has keenly encouraged and supported deeper integration of the Western Balkans with the international community. Expressing the desire to see the Balkans as “an integral part” of Europe rather than part of its periphery,25 the Turkish government has offered Western Balkan states support and technical assistance in fulfilling EU criteria. Turkey has supported the accession of Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as Montenegro and Macedonia into NATO. Turkey has also been working for the international recognition and integration of Kosovo, since the latter declared its independence in February 2008. It especially conducted intensive lobbying in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), encouraging a number of Muslim countries to recognize Kosovo.26

Meanwhile, in accordance with its “regional ownership” principle, Turkey has placed primary importance on regional initiatives for cooperation and stability. It has encouraged further institutionalization of the SEECP, the strengthening of its role and activities, and the gradual takeover of the functions of international institutions and missions by regional and local actors. With this policy, it has aimed to break the influence of outside powers over the Balkans and empower the regional actors, including itself, in resolving their own problems.

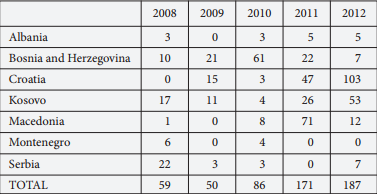

As previously mentioned. increasing economic cooperation and interdependence with the region has been among the key objectives of Turkey. Accordingly, the AK Party government has spent considerable effort for the coordination and facilitation of Turkish business activities in the Balkans. The “regional cooperation and competition strategy” adopted by the Turkish Ministry of Economy for the Balkans includes conducting continuous dialogue with Balkan states to facilitate trade and investments, promoting Turkish products and services, informing Turkish entrepreneurs of business opportunities, encouraging cooperation among Turkish and local enterprises and providing support to Turkish business associations and finance institutions operating in the region. Since 2011, the Turkish Ministry of Economy has regularly convened a Balkan States Working Group with representatives from various public institutions, business chambers, and NGOs to discuss the economic relations with the region and develop further strategies. All these efforts contributed to the increase in Turkish exports and investments in the Western Balkans (See Table 2 and 3 below).

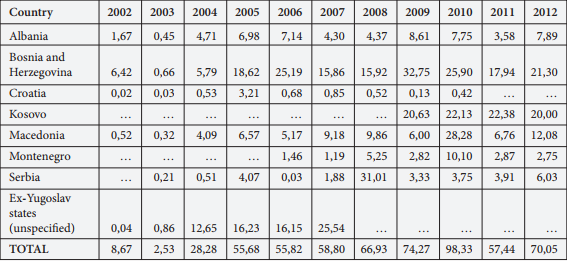

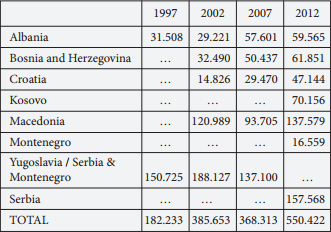

To accelerate development in the region, Turkey has continuously sent development aid to Western Balkan countries. While the allocations for each country have shown somewhat large fluctuations, the aggregate amount sent to the Western Balkans from the mid-2000s onwards has been substantially larger than before (Table 1).

Table 1: Official Development Aid from Turkey (gross, million $)

Source: OECD.

Social and Cultural Projects

As a response to the growing role and power of social forces and the importance of perception management in international relations,27 the AK Party government has developed and implemented public diplomacy and soft power instruments.28 In addition to its diplomatic and economic dynamism, it has carried out various social and cultural projects in the Western Balkans. A number of public institutions took part in this aspect of Turkey’s Balkans policy:

Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA): This public agency, which is responsible for providing developmental assistance and social-cultural projects abroad, is among the leading foreign policy agents of Turkey in the Western Balkans, almost functioning as a parallel diplomatic institution responsible for the socio-economic aspects of Turkey’s policy. It operates in all of the six countries in the region. Among its tasks are carrying out developmental projects, particularly in the areas of education, health and agriculture, providing assistance to municipal projects, renovating Ottoman buildings and artifacts and coordinating the activities of local and Turkish NGOs. While the bulk of the developmental projects have so far been focused on the Muslim communities, the agency also carries out projects for non-Muslims both for humanitarian reasons and to strengthen Turkey’s image..29

Existence of a sizable Muslim community with a shared Ottoman past has long been a strong factor shaping the interest of members of the AK Party and its precursors in the Balkans

Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB): Established in 2010 as another public institution attached to the Prime Ministry. In addition to providing assistance to Turkish citizens living abroad, its mission is to enhance Turkey’s social, economic, cultural, and educational relations with the broadly-conceived “kin and related communities.”30 Among the key functions of this institution are supporting and coordinating NGO activities and providing scholarships for international students. Students from Balkan countries can apply to a number of different scholarship programs, including one accepting applications from the citizens of this region only.

Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet): This institution, whose primary responsibility is to provide religious services and education in accordance with the secular ideology of the Turkish Republic, has been functioning as another channel of Turkey’s foreign relations by developing contacts with Muslim communities abroad. During the AK Party period, the Diyanet has intensified its dialogue and cooperation with Islamic communities in the Western Balkans. Thanks to the financial support provided by its affiliate foundation, this institution has also supported religious education in the region and actively took part in the construction and restoration of mosques.

Yunus Emre Institute: Established in 2007, the Yunus Emre Institute is a public foundation responsible for promoting Turkish language and culture abroad. 8 of its total 23 branches are operating in the Western Balkans and two new branches will be opened soon.31 Within only a few years of operation in the region, this institute attracted significant interest in the Turkish language, particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Turkish has become an elective language in secondary schools.32

Municipalities: A number of municipalities in Turkey have been organizing social and cultural activities, providing humanitarian aid and undertaking construction and renovation projects in the Western Balkans, mostly in places having historical or social connections with their inhabitants or simply those inhabited by Turks or Muslims.

The contribution of non-state actors

Turkey’s dynamism in the Western Balkans owes much to the increased involvement of Turkish civil and business actors for the last couple of decades. Their activities, which are often supported by the government, have played a significant role in strengthening social and economic ties between Turkish and Balkan people, and improving Turkey’s image and visibility.

a. Civil society and NGOs

Prior to the 1990s, Turkey’s foreign relations were planned and conducted exclusively by the state, not only because civil society was too weak and disinterested in contributing to foreign policy, but also the state would not readily welcome such a contribution. However, this situation changed rapidly in the aftermath of the Cold War. Especially the Bosnian War increased the awareness of Turkish society towards the Balkans; conferences were organized under the leadership of NGOs along with some municipalities.33 From the early 1990s onwards, Turkish civil society groups and NGOs, based both in Turkey and in the Western Balkans, have gradually proliferated and spread throughout the region. These groups and organizations, many of which are affiliated to religious brotherhoods, have carried out intensive charity activities, especially in the field of education. They have established universities34 and dozens of primary and secondary schools, and provided scholarships to students at all levels. They have undertaken a wide array of social and cultural projects as well. While engaging in collaborative efforts with state institutions such as TİKA, YTB and YEE, these groups and organizations have usually conducted their activities individually and according to their own vision and agendas.

Turkey spearheaded a trilateral consultation mechanism with Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia to achieve a lasting reconciliation

b. Businessmen and firms

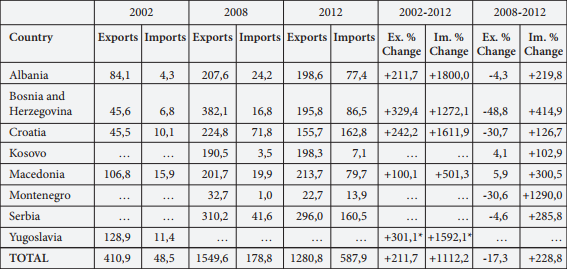

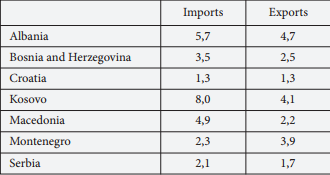

After the fall of the Communist regimes, Turkish businessmen became interested in the region as the Balkan states swiftly took the course of liberalization by opening up their markets to foreign capital and gradually privatizing state-owned enterprises. Yet, due to the slow pace of liberalization in the Western Balkans and the lack of resources and experience of Turkish firms to compete in the international arena, Turkish investments and reciprocal trade remained limited, both geographically and in size, during the 1990s. In the following years, however, thanks to the faster pace of liberalization in the region in accordance with EU accession requirements, the economic growth and entrepreneurial dynamism in Turkey, the conclusion of bilateral free trade agreements, and the encouragements offered by governments Turkish business activities in the Western Balkans intensified rapidly and trade and investments became more varied in sectorial and geographical terms. As a result, the trade volume between Turkey and the Western Balkans increased by 307 percent between 2002 and 2012.

Table 2: Turkey’s Foreign Trade with Balkan Countries (million €)

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute

(* The aggregate amount of trade with Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia is taken for the year 2012).

Until 2004, Turkey’s yearly foreign direct investment (FDI) outflow to the Balkans used to be almost exclusively to Bulgaria and Romania. From that year onwards, Turkish investments began to flow in the Western Balkans as well, due to the accelerating liberalization in these countries as well as bilateral agreements with Turkey. While the Western Balkan governments have been inviting foreign investment to encourage a liberal economy and competition, which are among the primary criteria for EU membership, Turkish firms are seeking to take advantage of the gaps in their market and industry as well as the absence of the free flow of capital and labor between these countries and Europe. There are currently more than 1.000 Turkish firms working in the Balkans as a whole with a total investment stock of 4,9 billion $.35 As of 2011, Turkey was the fifth country having the largest share in FDI stocks in Albania,36 while as of March 2013 Turkey was the third country with the largest investments in Kosovo after Slovenia and Germany.37 The share of Turkish stocks in the remaining Balkan countries is relatively lower.

Turkish investments in the Western Balkans are in various sectors including strategic ones like telecommunication, energy, transportation, and finance. Some airport facilities, including the international airports of Skopje and Pristina, have been built and/or run by Turkish companies.38 Albania’s public telecommunication company ALBtelecom was acquired by a Turkish consortium in 2007. Turkish banks have been operating in Western Balkan countries since the early 1990s and have become more active during the last few years.39 Some Turkish firms and consortiums have undertaken large construction and housing projects, while a larger number of smaller Turkish enterprises operate in the manufacturing and services sectors.

Table 3: Yearly FDI Inflow from Turkey (million $)

Sources: Central Bank of Turkey, Kosovo Statistics Agency. The figures for Kosovo are converted from Euro to US Dollar according to the yearly averages provided by IRS.

While many observers and politicians in the region indicate that Turkey is still not fulfilling its economic and industrial potential in the region and expect further investments and trade,40 the progress in Turkey’s economic activity in the Western Balkans in the last decade has been impressive. After all, Turkey’s economic presence is relatively new compared to other leading investors and trading partners of the region and the speed of foreign investment and trade depends on a number of different factors including rational calculations of firms and the political, economic and social conditions as well as the extant regulations in recipient countries. Barring an unexpected economic or financial crisis in Turkey, it can be estimated that Turkish capital and goods will continue to flow into the region’s economy.

In short, civil society and business actors have been playing an important role in consolidating Turkey’s position in the Western Balkans. Their activities and increased cooperation with public institutions have in turn led to the development and implementation of larger and more numerous projects, as well as a swift and notable penetration of Turkish entrepreneurs in the region. All this has strengthened social, cultural, and economic ties between Turkey and the Western Balkans.

Policy Implications: An Evaluation

A “Zero Problems” Era

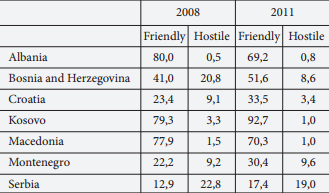

Contrary to the claims that the AK Party’s “zero problems with neighbors” foreign policy vision has failed, Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans have enjoyed a golden age since the mid-2000s. During these years inter-governmental relations have deepened, trade volume has multiplied, social ties have strengthened and Turkey’s image in the eyes of the Balkan people has become more positive than ever. Certainly, the absolute absence of problems and tensions with neighboring countries and societies would be unimaginable, and a few minor disputes and differences of opinion have actually taken place between Turkish and Western Balkan governments. Nevertheless, as Davutoğlu indicates, the “zero problems” principle is rather the endeavor to “eliminate the barriers preventing Turkey’s reintegration with its neighbors” and to maximize cooperation with them.41 Accordingly, large-scale disputes and conflicts of interest are avoided, or set aside if already present, and mutual understanding and cooperation are sought in alternative areas. If Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans are assessed in these terms, it can be claimed that Turkey has successfully implemented the “zero problems” doctrine in this region so far. While no serious crisis between Turkey and a Western Balkan government has taken place in recent years, economic relations have strengthened, Turkey’s image in the region improved considerably –perhaps with the exception of Albania– (Table 4).42 Furthermore, public interest in and familiarity with Turkish culture has grown43 and, notwithstanding transient fluctuations, an increasingly higher number of tourists have visited Turkey in recent years (Table 5).

Table 4: Public Attitude Towards Turkey (%)

Source: Gallup Balkan Monitor

Table 5: Western Balkan Nationals Visiting Turkey

Source: Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism

In the Western Balkans, the AK Party government has largely adhered to its “zero problems” doctrine. Politically, Turkey has prioritized the maintenance of peace and stability, the intensification of regional cooperation and the resolution of disputes through dialogue. Economically, it has pursued the objective of increasing its exports and investments and resorted to encouragements and bilateral agreements to foster trade. The Turkish government also has extensively used soft power instruments to promote cooperation and to improve its image and prestige. For all these reasons, the government has also endeavored to facilitate and encourage the activities of civil society and business actors.

The “zero problems” doctrine has so far worked far more smoothly in the Western Balkans compared to other surrounding regions, particularly the Middle East. This is because of the fact that the materialization of foreign policy visions and strategies goes beyond the capabilities and dedication of the agent and depends equally on favorable international and regional conditions. In the Middle East, internal dynamics as well as structural and conjunctural factors such as the unforeseen Arab revolutions, the prolonged civil war in Syria, the coup d’état in Egypt, and the alignments among regional and global powers led to unexpected situations for Turkey. As regards the Western Balkans, Turkey has taken advantage of the coinciding interests and objectives of the states in the region as well as the contribution of international organizations to regional stability.

Turkey’s dynamism in the Western Balkans owes much to the increased involvement of Turkish civil and business actors strengthening social and economic ties

Although indigenous social and political dynamics of the region came to the fore after the end of the Cold War, the Western Balkans are still very much under the influence of certain international powers. In order to stop the human tragedy and resolve the political instability created by the Bosnian and Kosovo Wars, first the United States and later the European Union became involved in regional politics. Especially the latter has been working to bring lasting stability to the Western Balkans and integrate this region into the international community through the incentive of EU membership. These efforts, which have been going on since the early 2000s, have profoundly influenced the choices of political actors and hence both domestic and international politics in the Western Balkans. In addition, the European Union has strengthened its position as a main actor in the larger Balkan geography with the membership of Bulgaria, Romania, and lately Croatia.

Being surrounded by the European Union, the Western Balkan countries do not have an alternative foreign policy vision to integration with Euro-Atlantic institutions, particularly with the European Union. This common objective has played a key role in maintaining peace and stability in the region. Political, ethnic and religious tensions have been far less intense than in the 1990s while dialogue and cooperation among regional actors has increased notably. The goal of accession to the EU has affected not only inter-state relations but also the domestic politics of the Western Balkan countries, as the governments have been respecting the principle of good and equitable governance more carefully than before and political and economic programs of rival political factions have converged to a great extent. As all these developments have fostered peace and stability in the Western Balkans, Turkey, in turn, has on the one hand supported and encouraged these integration processes and on the other hand benefited from the state of tranquility in advancing its social and economic relations. Thanks to the absence of a large-scale crisis in the region, Turkey was able to avoid sharp divisions and confrontations and through its balanced and cooperative policy it has remained on good terms with all governments in the region.

The “zero problems” doctrine has so far worked far more smoothly in the Western Balkans compared to other surrounding regions, particularly the Middle East

The economic conjuncture in recent years has also been to Turkey’s advantage. While Turkey was able to maintain its fiscal discipline and economic progress under the AK Party rule, the financial crisis and concomitant economic difficulties in the Euro zone, especially Greece, which is another aspirant regional power, have opened new opportunities for Turkish investors while increasing the demand in the Western Balkans for closer economic cooperation with Turkey.44 Almost all political actors in the six Western Balkan countries, regardless of their political ideology, express their willingness to cooperate with Turkey in economic matters.45

Golden Age in Decline? Challenges and Shortcomings

Despite the significant advancement of Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans, the future of this trend is somewhat uncertain. In fact, Turkey’s diplomatic activism in the Western Balkans slowed down after the Arab Spring and the ensuing crises in the Middle East. Due to security, economic, and humanitarian concerns, the focus of Turkish foreign policy in the recent few years has shifted to the affairs of the Middle East. As a result of the decline in Turkey’s interest in Balkan politics and other conjunctural factors, the diplomatic initiatives that Turkey had launched a few years before did not progress as expected. The trilateral mechanism among Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia virtually lapsed due to Croatia’s membership to the European Union. From 2011 onwards, the normalization process between Serbia and Kosovo has been facilitated by the European Union, leaving Turkey no room for mediation. Nor has the Islamic leadership problem in Serbia been resolved due to the lack of interest of the two parties in dispute to compromise, and Turkey’s offer for mediation has not brought anything but disillusionment from the both sides, each of which had apparently hoped Turkey would support its position.46 Finally, the trilateral dialogue process involving Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia came to a halt after the Serbian president declared in December 2013 that he would not attend the forthcoming meeting of the mechanism.47 This decision was a reaction to a speech that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gave in Kosovo in late October 2013, in which he declared “Kosovo is Turkey, Turkey is Kosovo” to express the political, economic, social, and cultural proximity of two societies.48 The Serbian government, which considered these words as an offense to Serbia’s sovereignty asked for an official apology from Turkey, and as this was not forthcoming, it decided to annul a number of minor bilateral agreements and suspend its high-level diplomatic dialogue with Turkey.

Although it was Erdoğan’s speech in Kosovo which seemingly led to the cooling of relations with Serbia, for many Serbians it was rather the last straw that broke the camel’s back. Despite the significant improvement in bilateral relations and of Turkey’s image in Serbia, the Serbian government, political parties and public were somewhat uneasy with Turkey’s lobbying for the recognition of Kosovo’s independence, as well as its preferential dialogue with and support for the Bosniaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina.49 All these actions, accompanied by frequent references of Turkish politicians to their Muslim “brethren” in Sarajevo, Skopje, and Kosovo, led to doubts as to Turkey’s sincerity towards Serbia, while reinforcing the conviction among the more conservative and nationalist Serbs, both in Serbia and abroad, that the AK Party was pursuing “neo-Ottomanism,” namely an amalgam of pan-Islamism and expansionism, in the Balkans.50 While the concerns of “neo-Ottomanism” has hindered the deepening of political relations with Serbia, despite the improvement of the Turkish image in recent years, a sizable portion of the non-Muslims in the Western Balkans still do not regard Turkey as a friendly country.51 Under these circumstances, how the attitudes and policies of the non-Muslim actors toward Turkey would have been if it had not been for Turkey’s impressive economic performance during the last decade is worth consideration as a counterfactual question.

Whether Turkey has been able to maximize its position of financial strength and stability in the context of the economic crisis is also questionable. As seen in Table 2 above, while the trade volume between Turkey and the Western Balkans has continuously increased since 2002, this has not always been steady. Between 2008 and 2012, despite the increase in Turkey’s imports from the region, the amount of Turkish exports dropped by about 17 percent, including a significant decrease in the exports to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Croatia. Although the major cause of this drop was arguably the rapid shrinkage in the economies of the Western Balkans, Turkey, which was less affected by the crisis compared to many other of its trade partners, could have benefited more from the economic conjuncture and enlarged its share in regional markets. Table 6 demonstrates that, with the exception of Kosovo,52 Turkey has not yet become a major exporter to any Western Balkan country. While the general increase in trade volume means that economic interdependence between Turkey and the Western Balkans is strengthening, one should also bear in mind that Turkish exporters will likely find more competitors in the region, as the effects of the global economic crisis fade. Similarly, as European economies recover from the current crisis, Turkish investors will have to engage in fiercer competition with their European counterparts in addition to those from countries like Russia, China, UAE and Azerbaijan, who have already shown their interest in the region. In this case, securing a strong economic position in the Western Balkans may become a much more difficult task for Turkey in the future.

Table 6: Turkey’s % Share in the External Trade of the Western Balkan Countries (2012)

Sources: European Commission, Kosovo Statistics Agency, Montenegro Statistical Office

Among other potential challenges for Turkey is the fact that the Western Balkans remains prone to polarization and conflict. While stability has generally prevailed in the region since the end of the 1990s, competition and rivalry continue among various groups and the memories of war are still fresh. Thus, it would be too early to claim that the possibility of conflict has disappeared completely. On the contrary, according to a Gallup poll conducted in seven Western Balkan countries in 2012, around one quarter of the participants expect an armed conflict in the region within five years.53 The Turkish government has so far enjoyed the stable atmosphere in the region to deepen multilateral relations and exert soft power, and has been careful not to openly side with a regional actor against another. Even if in a regional dispute its position leaned towards one of the parties, Turkey has acted carefully not to alienate the other party and rather encouraged both sides towards dialogue. As a result, Turkey has remained on largely good terms with all actors in the region. Yet, in case of a large-scale political crisis or conflict, Turkey’s strategic and/or ethical considerations may induce it to take a side, as it has recently done in the Middle East.54Relaxing the “zero problems” outlook in the Western Balkans can in turn lead to a sharp decline in Turkey’s relations with some actors in the region and rekindle anti-Turkish sentiments and propaganda.

Conclusions

When assessed in general terms, the Western Balkans has been a success story in Turkey’s foreign policy under the AK Party government and demonstrated the operability of Davutoğlu’s “zero problems” doctrine within a stable international environment. This is partly due to favorable political and economic conditions, and partly due to the government’s balanced and cooperative approach. As no large-scale crisis occurred in the Western Balkans during the last decade, Turkey was able to avoid sharp divisions and confrontations, while the dire economic situation in the region created new opportunities for Turkish businesses. Under these circumstances, the Turkish government preferred cooperation and dialogue over polarization and confrontation. Although identity-based motivations have always been present in Turkey’s engagement with the Western Balkans, the government has been careful to maintain a balanced approach, emphasizing historical and religious ties with the region without forsaking its economic interests. It has also endeavored to contribute to the maintenance of peace and order, the resolution of disputes, the fulfillment of structural reforms and the development of the entire region. Consequently, Turkey has been able to advance its relations with a wide spectrum of actors, improve its image and strengthen its economic position in the Western Balkans.

In the long term Turkey’s position in the Western Balkans will depend very much on the degree of trust and credibility it will earn

At the turn of the 2010s, Turkey appeared to be gaining a stronger political role in the Western Balkans, due both to its activism and the decrease in the EU’s interest in the region. Yet, contrary to expectations, Turkey’s political influence and leverage over regional politics has not tangibly increased. Neither Turkey’s regional initiatives, nor its calls to promote the political role and influence of the SEECP have yielded any significant results. Moreover, for the last few years, Turkey’s other foreign policy entanglements have been diverting its attention away from the Western Balkans, and it is difficult to foresee whether it will resume its activism in a near future. Given that the EU accession process of the Western Balkan countries continues and its own membership prospect in the Union remains in limbo, Turkey’s political influence over the Western Balkans is likely to remain limited. Under these circumstances, it would be prudent for Turkey to maintain its balanced, “zero problems” approach and (re-)establish itself in economic and cultural terms while using its membership to NATO and other international and regional institutions as a source of political power and leverage.

Finally, it should be emphasized that in the long term Turkey’s position in the Western Balkans will depend very much on the degree of trust and credibility it will earn.55 Based on public polls, the increase in cultural, educational, and touristic activities indicate that the Turkish image in the Western Balkans is improving, but it is after all up to Turkish state and non-state actors to maintain this positive trend. The mistrust and suspicions towards Turkey will continue, especially among the non-Muslims, if Turkish officials adopt emotional discourses harping too much on its Ottoman past or if Turkey relinquishes its balanced attitude in approaching the region. Turkey can also lose its credibility even among the Muslims if Turkish authorities, as well as civil and business actors, make promises that exceed their capacities.56 Establishing a stronger sense of trust and credibility, on the other hand, will secure Turkey’s close relations with the Western Balkans and lay the groundwork for the regional integration that Turkey seeks to achieve.

Endnotes

- This article is a substantially revised version of my earlier analysis published by SETA Foundation: “Turkey’s Zero Problems Era in the Balkans,” SETA Analysis, No. 1, October 2013. I would like to thank SETA for the research support and to Nedim Emin for his assistance.

- See, for example, Piotr Zalewski, “How Turkey Went From ‘Zero Problems’ to Zero Friends,” Foreign Policy, August 22, 2013; Laure Marchand, “La Turquie veut enrayer son déclin diplomatique,” Le Figaro, August 29, 2013.

- Rather than being a geographical term, Western Balkans refers to the Balkan countries that are outside the European Union. As other dynamics, actors and rules operate in Turkey’s relations with EU member countries, this article focuses on Turkey’s relations with the Western Balkans only.

- Mustafa Türkeş, “Türkiye’nin Balkan Politikasında Devamlılık ve Değişim,” Avrasya Dosyası, Vol. 14, No. 1 (2008), pp. 253-80; Othon Anastasakis, “Turkey’s Assertive Presence in Southeast Europe: Between Identity Politics and Elite Pragmatism,” Kerem Öktem, Ayşe Kadıoğlu, and Mehmet Karlı (eds.), Another Empire? Turkey’s New Foreign Policy in the 2000s (İstanbul: Bilgi University Press, 2012), pp. 185-208.

- Sabri Sayarı, “Turkish Foreign Policy in the Post-Cold War Era: The Challenges of Multi-Regionalism,” Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 54, No. 1 (2000), pp. 169-82.

- For a summary of these concerns and motivations, see Erhan Türbedar, “Turkey’s New Activism in the Western Balkans: Ambitions and Obstacles,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2011), pp. 140-2.

- Kâmil Mehmet Büyükçolak, “Soğuk Savaş Sonrası Dönemde Türk-Yunan İlişkilerinde Yeni Bir Boyut: Balkanlar,” Birgül Demirtaş-Coşkun (ed.), Türkiye-Yunanistan: Eski Sorunlar, Yeni Arayışlar (Ankara: ASAM, 2002), pp. 138-40; Birgül Demirtaş-Coşkun, “Turkish-Bulgarian Relations in the Post-Cold War Era: The Exemplary Relationship in the Balkans,” Turkish Yearbook of International Relations, No. 32 (2001), p. 33.

- Davutoğlu has been a key figure shaping Turkish foreign policy since 2002, first as the Chief Advisor of the Prime Minister on foreign affairs and later as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

- Ahmet Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik (İstanbul: Küre, 2001), pp. 316-21.

- Burhanettin Duran, “JDP and Foreign Policy as an Agent of Transformation,” Hakan Yavuz (ed.), The Emergence of a New Turkey: Democracy and the AK Parti (Salt Lake City, UT: The University of Utah Press, 2006), p. 292; Kemal Kirişci, “The Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy: The Rise of the Trading State,” New Perspectives on Turkey, No. 40 (2009), p. 42.

- Kadri Kaan Renda, “Turkey’s Neighborhood Policy: An Emerging Complex Interdependence?” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 1 (2011), pp. 89-108; Hasan Basri Yalçın, “Türkiye’nin ‘Yeni’ Dış Politika Eğilim ve Davranışları: Yapısal Realist Bir Okuma,” Bilgi, No. 23 (2011), pp. 35-60. For Davutoğlu’s remarks about “re-integrating the Balkans, the Middle East and Caucasia,” see, “Address of H.E. Prof. Ahmet Davutoğlu Minister of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Turkey,” Halit Eren (ed.), The Ottoman Legacy and the Balkan Muslim Communities Today Conference Proceedings (Sarajevo, BALMED, 2011), 19.

- For the concepts of “asymmetrical interdependence,” “sensitivity” and “vulnerability,” see Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye’s classical work Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co., 1977), chapter 1.

- “Address by H.E. Ahmet Davutoğlu, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey at the Ministerial Meeting of the SEECP, 22 June 2010, İstanbul,” Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/address-by-h_e_-ahmet-davutoglu_-minister-of-foreign-affairs-of-republic-of-turkey-at-the-ministerial-meeting-of-seecp_istanbul.en.mfa.

- Thanks both to its sensitivity to the plight of Muslims abroad and its close contacts with the Bosniaks in Europe, the National Outlook movement was among the first groups in Turkey that organized demonstrations during the Bosnian War and urged the Turkish government to act on behalf of the Muslims: Kerem Öktem, “Global Diyanet and Multiple Networks: Turkey’s New Presence in the Balkans,” Journal of Muslims in Europe, No. 1, (2012), p. 30.

- Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik, p. 316.

- Kerem Öktem, New Islamic Actors after the Wahhabi Intermezzo: Turkey’s Return to the Muslim Balkans, (Oxford: European Studies Centre University of Oxford, 2010).

- Altin Raxhimi, “Davutoglu: ‘I’m Not a Neo-Ottoman’,” Balkan Insight, (April 26, 2011), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/davutoglu-i-m-not-a-neo-ottoman.

- Interviews with diplomats at the Turkish embassies and bureaucrats at the TİKA offices in Skopje, Podgorica, Belgrade and Sarajevo, September-November 2013.

- Dimitar Bechev, “Turkey in the Balkans: Taking a Broader View,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 14, No. 1 (2012), p. 137.

- “New Beginnings in the Balkans?” ISN ETH Zürich, (May 21, 2010), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Articles/Detail//?id=116496.

- “Türkiye-Bosna-Hersek-Sırbistan Üçlü Zirve Toplantısı’nda kabul edilen Ankara Zirve Bildirisi, 15 Mayıs 2013, Ankara,” Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-bosna-hersek-sirbistan-uclu-zirve-toplantisi_nda-kabul-edilen-ankara-zirve-bildirisi_-15-mayis-2013_-ankara.tr.mfa

- “Mostar Köprüsü’nün önünde barış mesajı,” Türkiye, April 29, 2010.

- “Ankara settles dispute between religious institutions of Sandzak,” Today’s Zaman, October 17, 2011.

- “Ahmet Davutoğlu Bosna hersek gezisini tamamladı,” Yeniçağ, January 30, 2011.

- Altin Raxhimi, “Davutoglu: ‘I’m Not a Neo-Ottoman.”

- “Türkiye, İKÖ ülkelerinin Kosova’yı tanıması için bastırıyor,” Zaman Amerika, March 10, 2008; “Sejdiu: SHBA dhe Turqia shtyllat kryesore të përkrahjes ndërkombëtare për Kosovën,” Bota Sot, February 27, 2013.

- As Alan Henderson underlines, “a country can become known, admired, and also rewarded” as a result of “doing good:” Alan K. Henrikson, “Niche Diplomacy in the World Public Arena: The Global ‘Corners’ of Canada and Norway,” Jan Melissen (ed.), The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), p. 68.

- İbrahim Kalın, “Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Turkey,” Perceptions, Vol. 16, No. 3 (2011), pp. 5-23.

- Increased contacts of the agency with local people in recent years have resulted in a larger number of projects been requested by non-Muslims: Interviews with TİKA officials in Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina, September-November 2013. In addition, many of our more than 100 interlocutors in the six Western Balkan countries (i.e., representatives of political parties, media corporations and NGOs) mentioned TİKA and praised its works while talking about Turkey.

- Kemal Yurtnaç, “Turkey’s New Horizon: Turks Abroad and Related Communities,” SAM Papers, No. 3 (2012), p. 4.

- These branches are in Albania (Tirana, Shkodër), Bosnia and Herzegovina (Sarajevo, Fojnica), Kosovo (Pristina, Peć, Prizren) and Macedonia (Skopje). The two forthcoming branches will be in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Mostar) and Montenegro (Podgorica).

- “Türkçe seçmeli mecburi yabancı dil oldu,” Haber 7, (December 27, 2011), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.haber7.com/dunya/haber/822993-turkce-secmeli-mecburi-yabanci-dil-oldu.

- Ali Bulaç, “Balkan Konferansı,” Zaman, October 27, 1994.

- These universities are International University of Sarajevo, International Balkan University (Skopje), Epoka University (Tirana), Bedër University (Tirana), and International Burch University (Sarajevo). The latter three are run by foundations affiliated with the Gülen (Hizmet) Movement.

- Interview with an official at the Turkish Ministry of Economy, August 2013.

- Turkey’s FDI stock constituted 282 million € of the 3,036 million € total. Source: Bank of Albania.

- Turkey’s FDI stock constituted 182,6 million € of the 2,582 million € total. Source: Central Bank of the Republic of Kosovo.

- Lavdim Hamidi, “Turkey’s Balkan Shopping Spree,” Balkan Insight, (December 7, 2010), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/turkey-s-balkan-shopping-spree; Dusan Stojanovic, “Turkey uses economic clout to gain Balkan foothold,” Today’s Zaman, March 16, 2011.

- Among state-owned banks, Halkbank has a subsidiary in Macedonia since 1993 and has recently opened a branch in Serbia, while Ziraat Bankası has been running in Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1997. A number of Turkish private banks and finance groups have also been operating in Balkan countries, such as Garanti Bankası and Fiba Holding (Credit Europe) in Romania, Çalık Group (BKT) in Albania, Türk Ekonomi Bankası in Kosovo and Süzer Group (Banka Brod) in Croatia.

- See, for example, Emine Şeçeroviç, “Bosna’da Türk yatırımları,” Zaman, January 26, 2013; Fatjona Mejdini, “Turqia, aleati me 9% investime në Shqipëri, por me rritje progresive të tyre,” Gazeta Shqip, August 8 2013; “Makedonya 650 milyonluk bir pazar,” Aktif Haber, (April 18, 2013), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.aktifhaber.com/makedonya-650-milyonluk-bir-pazar-770800h.

htm; “Serbian President Tomislav Nikolic Conferred With Turkish President Abdullah Gul,” InSerbia,

(May 15, 2013), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://inserbia.info/news/2013/05/serbian-

president-tomislav-nikolic-conferred-with-turkish-president-abdullah-gul/. - Ahmet Davutoğlu, “Zero problems in a new era,” Foreign Policy, March 21, 2013.

- Many politicians and observers underline the growth of economic relations and the success of Turkish businesses as a key factor in the improvement of Turkey’s image in the Balkans: Interviews with spokespeople of NOVA, PCG and FORCA (Montenegro); PDK, LDK and VV (Kosovo); SDSM and TDP (Macedonia); Rifat Fejzić (the Chief Mufti of Montenegro) and Darko Šuković (journalist, Radio Antena M, Montenegro), September 2013.

- Menekşe Tokyay, “Balkan countries discover Turkey through the arts,” SETimes, (July 31, 2013), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2013/07/31/feature-04. This also owes much to Turkish soap operas, which are widely watched throughout the region: Interviews with Gerti Bogdani (politician, PD, Albania), Vasilije Lalošević (politician, SNS, Montenegro), Vesna Šofranac (editor in chief, Pobjeda, Montenegro), Muhamed Zeqiri (editor in chief, Alsat-M TV, Macedonia), Miodrag Radomirović (Director, Radio Kiss, North Kosovska Mitrovica), and Elvir Švrakić (CEO, Hayat TV, Bosnia and Herzegovina), September-November 2013; also see Ivana Jovanovic and Menekşe Tokyay, “TV series fosters Balkan, Turkey relations,” SETimes, (December 21, 2012), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2012/12/21/feature-04).

- For a discussion on the central role of international political and economic circumstances in the growth of Turkey’s presence in the Balkans, see Bechev, pp. 133-7.

- Interviews with spokespeople of PD (Albania); PDK, LDK and VV (Kosovo); SDP, PCG and FORCA (Montenegro); SNS, DSS, SPO, URS and VMSZ (Serbia); SDA, SDP, SBiH, HDZ 1990 and HDZ BiH (Bosnia and Herzegovina), September-November 2013. See also the interview with Milorad Dodik, the President of Republika Srpska: Ayhan Demir, “Türkiye güçlü bir ülke,” Yeni Akit, July 15, 2013. The new Socialist government in Albania is also looking for a strategic partnership with Turkey: Linda Karadaku, “Albania moves to a strategic partnership with Turkey,” SES Türkiye, (October 24, 2013), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://turkey.setimes.com/en_GB/articles/ses/articles/features/departments/world/2013/10/24/feature-01.

- Interviews with the leaders of the two Islamic communities, Adem Zilkić and Muamer Zukorlić, November 2013.

- “Nikolić do daljeg ne učestvuje na sastancima Srbije, Turske i BiH,” Vecernje Novosti, December 14, 2013.

- For comments on Erdoğan’s visit to Kosovo, see, Mehmet Uğur Ekinci and Nedim Emin, “Yerel ve Bölgesel Siyaset Bağlamında Erdoğan’ın Kosova Ziyareti,” SETA, (October 25, 2013), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://setav.org/tr/1/yorum/12134.

- Interviews with the spokespeople of SNS, SPS, DS, DSS, and SRS, October-November 2013.

- For criticism of “neo-Ottomanism” by Serb authors, see Darko Tanasković, Neoosmanizam: Povratak Turske na Balkan (Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik, 2011); and the special issue of Politeia, No. 2 (2011). During our interviews, Vladan Glišić of the Dveri Srpske and Živadin Jovanović, Serbia’s Former Minister of Foreign Affairs, also expressed their concerns about Turkey’s “neo-Ottoman” policies.

- See Table 4 above and Žarko Petrović and Dušan Reljić, “Turkish Interests and Involvement in the Western Balkans: A Score-Card,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2011), p. 160.

- Interestingly enough, Turkey was able to secure 8 percent of this country’s total imports despite the absence of a free trade agreement. The free trade agreement between Turkey and Kosovo was concluded only recently, on September 27, 2013.

- Gallup Balkan Monitor (2012), retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.balkan-monitor.eu/

- Actually for Davutoğlu taking a clear “national position” is a better response to crises than remaining neutral, as it is the only way “to shape history”: From his speech at LSE, London, March 7, 2013.

- I would like to thank Ahmet Alibašić for this remark.

- Observers have long warned that Turkey should maintain the balance between reality and rhetoric in the Balkans. See, for example, Şaban Çalış, Hayaletbilimi ve Hayali Kimlikler: Neo-Osmanlılık, Özal ve Balkanlar (Konya: Çizgi, 2001), p. 151; Mehmet Özkan. “Türkiye’nin Balkan Politikası,” Öner Buçukçu (ed.), Balkan Savaşlarının 100. Yılında Büyük Göç ve Muhacerat Edebiyatı Sempozyumu Bildiriler (Ankara: Türkiye Yazarlar Birliği, 2013), pp. 213-5; Petrović and Reljić, p. 169.