Introduction1

Little-known to the outside world in the wake of the Soviet Union’s dissolution, Central Asia occupies a more prominent place in international affairs today. Its strategic importance in the geopolitical and energy calculi of Russia, China, and the United States, in addition to India, Turkey, Iran, and countries of Europe and Asia has grown in the recent decade. Among the five Central Asian republics, three have extensive oil and natural gas deposits. Kazakhstan’s Tengiz oil and gas field is the sixth largest oil field in the world. With over 170 oil fields, the country possesses nearly three percent of global oil reserves,2 and its proven gas reserves rank 15th in the world.3 In 2011, auditors from Gaffney, Cline & Associates estimated Turkmenistan’s gas reserves as second only to Russia’s proven natural gas reserves. The volume of Uzbekistan’s natural gas deposits is modest compared to the natural endowments of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. It nonetheless has an abundance of fossil fuels available for domestic consumption and export.

The growing presence of China, the world’s largest energy consumer, in the Central Asian energy sector has been disconcerting to Russia, whose political clout in the region has been largely contingent on its access to energy resources and exclusive control over energy transportation routes. Many analysts have predicted that the colliding interests of Russia and China in Central Asia would inevitably lead to a rupture in the relationship between the two great powers.4 Contrary to these grim predictions, Moscow and Beijing have been able to avoid political disputes. The dominant explanations for the placidity of Sino-Russian relations have given little heed to the role played by “secondary” states caught in the midst of the greater powers’ competition over power, resources, and influence. Yet history is replete with examples of these less-powerful states escalating great powers’ tensions and contributing to regional and global crises. The Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign an association agreement with the EU prompted mass protests in Ukraine that deposed the president but also provided a pretext for Russia’s eventual annexation of Crimea. The Georgia-Russia “gas and wine wars” pitted Moscow against Europe and the U.S. These and other examples demonstrate how “secondary” states’ foreign policy choices can have wider consequences and implications.5

By making tactical concessions to Moscow, while expanding its cooperation with Beijing, Kazakhstan has been able to deflate Russia’s fear of losing its relative power position in the region

This study illuminates the role of Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy in preempting the emergence of issues conducive to the rise of tensions in Sino-Russian relations. By making tactical concessions to Moscow, while expanding its cooperation with Beijing, Kazakhstan has been able to deflate Russia’s fear of losing its relative power position in the region. By leveraging big partners against each other, Astana has contributed to a balance of power in Central Asia where neither state has been able to have an upper hand in either the military-political or economic realm.

The article begins with an overview of the heightened competition over Central Asian energy resources followed by a brief discussion of explanations of cooperation between Moscow and Beijing. In the second part, we examine the concrete strategies employed by the Kazakh government to safeguard its independence and to mitigate tensions in relations between Russia and China by means of multi-vectorism.

Conditions for Sino-Russian Rivalry in Central Asia

Central Asia has always mattered to Moscow. In the 1990s, Russia’s economic, political, and military problems stymied the realization of the Kremlin’s goal of regaining influence in the former Soviet states. The global economic situation at the beginning of the 21st century was favorable to Russia’s Central Asian ambitions, while the post-9/11 context provided Moscow with a pretext for stepping up its involvements in the region’s security realm. During Vladimir Putin’s tenure as President and Prime Minister of Russia, Moscow significantly expanded its security and economic cooperation with the Central Asian states. Russia leveraged its access to Central Asian natural resources and control over energy transportation routes to promote its geopolitical and economic interests in the region.

From an economic standpoint, the resale of cheap Central Asian gas and oil to European customers, and the use of imported energy for government-subsidized domestic consumption, afforded Russia considerable direct benefits at a time of high world market prices for energy resources. The Russian monopoly over gas and oil transportation routes provided the Kremlin with a powerful bargaining chip in negotiations for lower import prices on Central Asian gas and oil.6 From a geopolitical perspective, exerting control over Central Asian energy resources became a viable strategy for reasserting Russian influence not only over the Central Asian republics, but also Ukraine and Georgia by means of rerouting cheap natural gas to these energy-dependent republics trying to escape Moscow’s orbit of influence. The domination of Central Asian energy exports also awarded the Russian government significant leverage vis-à-vis member-states of the European Union dependent on Russia’s energy supplies.

Russia’s monopolistic aspiration in the Central Asian energy sector has been challenged by China’s rapidly growing energy demands.7 While the bulk of China’s oil imports originate in the Middle East, Central Asian energy resources have become increasingly attractive to the Chinese government due to the ongoing political instability in the Persian Gulf region and the remoteness of the Middle East petroleum wells. Beijing has invested heavily in oil and gas field development in Central Asia, as well as in constructing or renovating the pipelines’ infrastructure to meet its demand for energy resources. Simultaneously with China’s growing presence in the Central Asian fossil fuels market, Chinese state enterprises have made inroads into various economic and industrial sectors of the Central Asian states. By 2007, China had surpassed Russia as the major trade partner in Central Asia with Astana becoming Beijing’s largest trading partner in the region.8 The 2008 global financial crisis further undermined Russia’s dominant position in the Central Asian energy sector. The diversification of energy networks allowed the Central Asian governments to strengthen their bargaining position vis-à-vis Moscow, which had been forced to pay near market price for Central Asian gas and oil.

Most of the analyses of Russian foreign policy consider it as an exemplar of realpolitik behavior explainable by the tenets of political realism.9 Realists of all genres characterize international politics in zero-sum terms and emphasize the enduring propensity for conflict among states vying for power and domination.10 The extent to which a state engages in power politics depends on its relative power position. In other words, a state’s foreign policy is ultimately driven by shifts in the distribution of power within an international system. In Central Asia, China’s rise has resulted in changes in Russia’s relative power position in the region. Given the centrality of energy politics to Russia’s international and regional standing, China, which has broken Russia’s monopoly on the transportation networks and eroded its share of the Central Asian energy market, represents a geopolitical rival to Moscow in the region.11 Subsequently, Russia and China have long been expected to experience increased tension in their bilateral relations.12 Why hasn’t Russia resorted to the familiar power politics consistent with realpolitik in its relations with Beijing?

Russia and China’s shared interests in maintaining a broader strategic partnership have been frequently noted as a mitigating factor to their conflicting aspirations. Signed into the 2001 Sino-Russia Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation, the strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing was fueled by fears of NATO’s eastward expansion. The Sino-Russian cooperation was cemented by shared apprehension and dismay over Western meddling in the domestic politics of sovereign states in the wake of the “color” revolutions in Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004-2005), and Kyrgyzstan (2005). Today, Russia and China continue challenging the U.S.-led liberal international order by establishing and promulgating their own rules for managing international relations and global security.

The lack of attention to the Chinese vector in Russian foreign policy has also been accounted for by the peculiarities of Russia’s geopolitical thinking and reasons of national identity that led Moscow to construe the West, especially the U.S., as its primary Other

The lack of attention to the Chinese vector in Russian foreign policy has also been accounted for by the peculiarities of Russia’s geopolitical thinking and reasons of national identity that led Moscow to construe the West, especially the U.S., as its primary Other.13 In addition, both Russia and China share common concerns about regional security, cross-border stability, and the inviolability of regimes, including authoritarian ones.14 The regional multilateral institutions, particularly the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), have been noted for their ability to provide forums for facilitating regional cooperation, particularly in counteracting the “three evil forces” of terrorism, extremism, and separatism.15

Critics of these explanations point out that a full-fledged alliance between Russia and China against the U.S. is out of the question as China, in particular, has strong disincentives for breaking its ties with the U.S. The Russian leadership has lingering fears of Chinese hegemony and a degree of distrust for the Chinese. The Russian political discourse has long tried to project the image of Russia as a Western and European nation, and many in the Russian political establishment question the suitability of Russia’s strategic partnership with China to Moscow’s national interests.16 The two countries have ongoing disagreements over the military vs. economic emphasis in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The Chinese leadership has also expressed disappointment with the Kremlin’s strengthening of its military ties with India, which has unresolved long-standing border issues, growing economic concerns, and lingering suspicions of China that resulted in the militarization of the shared border regions in both states.

To these critiques of the dominant explanations of Sino-Russian relations, we add their neglect of the role played by the Central Asian republics themselves. The latter has been deemed to have little autonomy in international relations except as the allies of great power states. Functioning in the shadow of the larger states, these “secondary” countries have been expected to comply with the great powers’ interests (i.e., “bandwagon”), ally with other states in an attempt to counterbalance the power of a preponderant state,17 or “hedge” by cultivating a middle position that forestalls or avoids having to choose one side at the expense of another.18

Contrary to this prevailing understanding, we argue that the Central Asian republics have grown the capacity to develop and employ strategies which have allowed them to overcome many of the handicaps of their lesser power status. One of these strategies is that of multi-vectorism. This refers to a type of foreign policy based on the principles of pragmatism, rejection of permanent alliances with any other nation, and a non-preferential and non-ideological basis of foreign relations.19 Multi-vectorism is different from both balancing and bandwagoning. It includes an ever-increasing range of approaches designed to increase a smaller state’s bargaining power in relations with greater powers by means of tactical maneuvering. In that, it resembles a “hedging” strategy, but is not limited to it since “wedging” tactics may be employed as part of the smaller state’s mutli-vector foreign policy strategy.20

In the following section, we demonstrate how several tactics utilized by Kazakhstan as part of its multi-vector foreign policy approach –in particular, the strategies of inclusion, tactical concessions, and diplomatic persuasion– have helped Astana maintain the perception of a strategic and geopolitical balance among the power players in Central Asia. These tactics have assisted Kazakhstan in enhancing its bargaining power in relations with Moscow and attaining greater autonomy in its foreign policy actions toward other states as well.

Kazakhstan’s Multi-Vector Strategies

The multi-vector approach to foreign policy has been the cornerstone of Kazakhstan’s foreign relations since its independence. Announced by Kazakhstan’s president Nursultan Nazarbayev in 1992 as part of the republic’s first foreign policy concept, it was designed with an explicit purpose of enabling the government of the newly independent state to pursue cooperative and non-ideological relations with other states in all directions of Kazakhstan’s foreign policy.21 Establishing relations with regional and global partners was imperative for Kazakhstan’s development. Its landlocked position and extensive borders with Russia and China imposed significant geopolitical constraints on Kazakhstan that were reinforced by its economic dependence on exports of natural resources, particularly oil and gas. By some estimates, energy exports account for nearly 70 percent of Kazakhstan’s total exports and constitute about 40 percent of government revenue.22 European consumers import around three-quarters of Kazakhstan’s crude oil, but delivering energy to the European partners ultimately depends on pipeline routes controlled by Russia. Thus, the Kazakh government has sought to offset Russia’s influence through the diversification of political and economic ties with other power centers in the region, including China, the U.S. and the European states. Under these conditions, Kazakhstan has engaged in what some have termed “opportunistic multi-alignment,” in which it simultaneously pursues “positive relations and advantages via-a-vis greater powers” and plays greater powers against each other.23

Astana’s strategy of inclusion has been used to ensure that no single country could attain exclusive rights to Kazakhstan’s energy sector

Consistent with its multi-vector principles, Kazakhstan has established cooperative and beneficial relations with Russia, China, the U.S., European countries, and other states with existing or potential bearing on the economic and political relations of the republic. In the economic and energy sector, for example, Kazakhstan has supported Moscow’s efforts at economic integration in the post-Soviet space and granted Russian companies control over the majority of Kazakhstan’s oil exports and a substantial share in the development of oil and gas fields.24 In 2014, Astana joined the Eurasian Economic Union along with Russia, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. Kazakhstan has also been central to Beijing’s economic initiatives in Central Asia. In late 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled his “One Belt, One Road” strategy. Encompassing the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road, the strategy pursues greater connectivity and cooperation between China and Central Asia through economic and transportation integration as well as cultural exchange.25 The Khorgos Gateway, a dry port connecting Kazakhstan to China by rail, has placed Astana at the center of Beijing’s initiative to construct the Europe-China rail link.

The framework of multi-vectorism has also been applied in Kazakhstan’s security relations. The republic has maintained strong defense ties with Moscow and has been a key player in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) spearheaded by the Kremlin. Astana provides important military facilities for Moscow, leasing more than 11 million hectares of the republic’s land for this aim, and partakes systematically in joint military exercises and training with other CSTO members. In 2010, the Kazakh government agreed to the establishment of the Collective Rapid Reaction Force (CRRF) of the CSTO advocated by Russia. Parallel to defense and military cooperation with Russia, Kazakhstan has intensified its cooperation with the U.S./NATO and Beijing. Using the framework of the Partnership for Peace program as the basis for cooperation with NATO, Kazakhstan has participated in numerous joint military events, exercises, and forums with NATO, and education and military training with the U.S.26 It is the only Central Asian republic whose peacekeeping battalion (KAZBAT) achieved an interoperability status with NATO’s peacekeeping force in 2008. Kazakhstan has also pursued military cooperation with China through the framework of the SCO. In December 2012, Kazakhstan and China agreed to enhance military-to-military cooperation in order to “deepen military ties.”27

The government of Kazakhstan has skillfully employed diplomatic tools and persuasion to reduce the Kremlin’s concerns over the loss of its footing in Central Asia

How has Astana’s multi-vector foreign policy strategy contributed to the mitigation of great power competition? To avoid antagonizing Kazakhstan’s larger neighbors, particularly Russia, while simultaneously pursuing its own national aims, the government of Kazakhstan has relied on the following tactics. First, the strategy of inclusion has always been a part of its multi-vector foreign policy, especially in the energy sector. The Kazakh government invited companies from Russia, China, and other interested countries to important tenders for energy development contracts, but it also capitalized on the temporary absence or weakness of one partner for developing economic and political ties with others states. For example, in the early 1990s, Russia almost completely disengaged from Central Asia, opting to forge a partnership with the West. The resulting vacuum of power and resources provided both an imperative and an opportunity for the Kazakh government to seek and establish foreign relations with other partners. During this time, Kazakhstan was able to secure Washington’s financial assistance and political backing for procuring financial aid from other Western countries and international financial institutions, which were indispensable to keeping the shattered Kazakh economy afloat.28 The established cooperative relations with the U.S. were later used as leverage in Kazakhstan’s difficult relations with Russia. During that time, Kazakhstan sustained its economic and military ties with the Russian state and invited its companies to participate in the energy tenders. In 1997, for example, the Kazakh government held an auction for developing the Aktobe oil field. The state-owned Chinese National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) made the best offer and won the tender for Aktobe, but other companies from Russia and China were also invited to take part in the bid.29 All in all, Astana’s strategy of inclusion has been used to ensure that no single country could attain exclusive rights to Kazakhstan’s energy sector. This strategy has helped to alleviate Russia’s fears of deception and cheating on what Moscow deemed as its own legitimate interests in the region since it effectively prevented other states from gaining a relative advantage in the republic’s energy sector.30

Chinese Vice Premier Gaoli (R) and Russia’s Deputy PM Dvorkovich (L) attend a signing ceremony after the annual meeting of the China-Russia Energy Cooperation Committee on September 20, 2017 in Beijing, China.SONG JIHE / CHINA NEWS SERVICE / Getty Images

Two other strategies that allowed Kazakhstan to keep the great powers’ tensions at bay and pursue its independent foreign policy goals have been tactical concessions to its partners to deflate their fears of losing their relative power position in the region and leveraging big partners against each other as a means of circumventing the dominance of either one of them. Kazakhstan’s maneuvering in the dispute over the demarcation of the Caspian Sea exemplifies the skillful application of tactical concessions and leveraging by its government. Although Astana preferred to see the Caspian Sea divided into several national sectors with each littoral state exercising exclusive authority over its sea segment, it informally conceded to Russia’s demands for establishing joint control of all littoral states over the Caspian Sea. This was done to conciliate Moscow, and thereby ensure an uninterrupted inflow of foreign direct investment into Kazakhstan’s oil and gas sectors. Later, the Kazakh government reverted to its favored position, having secured support from Western oil companies which began drilling in the Kazakhstan sector of the Caspian Sea. Pressure from Western companies interested in having the Caspian basin divided into national economic zones compelled the Russian government to backtrack on its initial position.31 In the end, an agreement reached in Aktau, Kazakhstan, in August 2018, between the five countries with shorelines on the Caspian Sea, reflects a compromise that treats the surface as international water and divides the seabed into territorial zones. An added stipulation that bans any country without Caspian shoreline from deploying military vessels in the sea has been perceived as a major victory for Moscow.32

The distribution of oil contracts for the Tengiz oil field, the largest proven onshore field in the post-Soviet territory, also exemplifies the use of tactical concessions by Kazakhstan. Following the creation of Tengizchevroil, a joint venture between the Kazakh government and American Chevron, which received the first oil contract for the Tengiz onshore field, Russia began obstructing the transfer of Tengiz oil through its Atyrau-Samara pipeline under the pretext of finding sulphur compounds in Kazakh oil. The Russian restrictions almost forced Chevron to drop out of the contract. The situation improved once the Kazakh government agreed to sell half of its share in the Tengizchevroil project to the Russian oil firm Lukoil. To avoid similar problems on another oil and gas project in Karachaganak, the Kazakh authorities invited Russia’s Lukoil into the Karachaganak project in 1995.33

Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism reveals the ability of a less powerful state to engage with and moderate relations among dominant actors with competing interests

In other energy projects, including those signed with Chinese firms, the Kazakh government made sure to keep significant stakes in the joint ventures to guarantee state control over the petroleum resources and maintain some ‘wiggle room’ to maneuver for accommodating competitors’ interests and averting their reprisals to Kazakhstan’s foreign policy choices.34 For instance, in 2005, when the CNPC was finalizing the purchase of PetroKazakhstan, the government of President Nazarbayev managed to take into its possession a third of PetroKazakhstan’s shares through the state-owned firm, KazMunayGas, which also serves as a regulator of the gas and oil industry in the republic.35 To assuage Russia’s concerns over China’s accession to Kazakhstan’s oil sector, the Kazakh government relied on its administrative control over the Kazakh court system to allow Russia’s Lukoil to acquire a controlling share in Turgai Petroleum, a subsidiary of PetroKazakhstan, in addition to awarding the Russian company with a lump sum of money in settlements over sharing Turgai Petroleum’s oil revenues.36 The case of Turgai Petroleum, which is jointly owned by Chinese and Kazakhstani state-owned companies (50 percent) and a Russian state-owned firm (50 percent), is exemplary, in that it demonstrates Kazakhstan’s ability to mitigate conflicting interests between great powers while simultaneously attaining its own domestic and foreign policy aims. As a result of these concessions, Russia was able to develop a robust position in Kazakhstan’s fuel and energy sector. Russia’s Lukoil operates seven projects in Kazakhstan and has shares in the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC). Two other Russian companies –Rosneft and Transneft– transport Kazakh oil through the Atasu-Alashankou and Atyrau-Samara pipelines. Russia’s Gazprom has a 50 percent stake in LLP KazRosGas established to consolidate efforts across a number of energy projects.37

Finally, the government of Kazakhstan has skillfully employed diplomatic tools and persuasion to reduce the Kremlin’s concerns over the loss of its footing in Central Asia. The Kazakh authorities have regularly assured the Russian government that Russian energy firms would be able to take part in multinational ventures operating in Kazakhstan.38 The Nazarbayev government has been careful to avoid antagonizing the Kremlin over Kazakhstan’s dealings with other states. In their public statements, Kazakh officials emphasize the positive dimensions in the mixture of cooperative-competitive interests characterizing Kazakhstan-Russia relations.39 For instance, the CPC pipeline, in which Russia holds a controlling 24 percent stake, has been presented as a model of cooperation between Kazakhstan and Russia. The expansion of the CPC pipeline formalized in 2011 has been portrayed as a sign of commitment to growing the commercial ties between these two countries and a symbol of confidence shared by these states in the long-term cooperation over oil transportation from Caspian Sea oil fields.40 With its increasing crude oil production, Kazakhstan has also been promoting pipeline expansion projects simultaneously with different parties –deals were signed to expand CPC and Kazakhstan-China oil pipelines respectively in January and April 2013.41

Another example of Kazakhstan’s diplomacy in the energy sector may be seen in the back-to-back visits of president Nazarbayev to China and Russia in 2011. Kazakhstan’s leader first paid a three-day state visit to China, where he met with Chinese president Hu Jintao, and the two sides signed a number of agreements in the spheres of energy, industrial financing, and transport.42 This visit also secured CNPC’s right to tap the Urikhtau gas field in western Kazakhstan.43 Several days later, the Kazakh president traveled to Moscow, where he held talks with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and vowed to boost strategic bilateral cooperation between Russia and Kazakhstan.44 In particular, Nazarbayev claimed that nearly all the oil produced in Kazakhstan would be transited through Russia.45 Both Russia and China understand that Nazarbayev’s words should be treated primarily as diplomatic rhetoric rather than solid promises. However, it is clear that his skillful discourse and activities have been effective in sustaining non-antagonistic relations with Kazakhstan’s great power neighbors on its northern and eastern borders.

Conclusion

We began this study by highlighting a puzzle in Sino-Russian relations in the energy sector in Central Asia. We asked why, despite its competing interests with China, Russia has been able to avoid political disputes with Beijing. While acknowledging the importance of the global great power dynamics and the presence of mutual interests that reinforce strategic cooperation between Moscow and Beijing, this study showed how the multi-vector foreign policy of Kazakhstan has contributed to mitigating potential conflict in Sino-Russian relations. Kazakhstan’s tactical concessions, strategies of inclusion, and diplomatic persuasion have allowed it to sustain a perception of balance in the relative power capabilities of dominant powers in Central Asia and foster a sense of legitimacy and acceptance of changes in the regional order. Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism reveals the ability of a less powerful state to engage with and moderate relations among dominant actors with competing interests. Russia’s foreign policy toward Kazakhstan has changed as well. Its influence has become more conciliatory than forceful and increasingly reliant on soft power tools, rather than threats or neglect of Kazakhstan’s interests.46

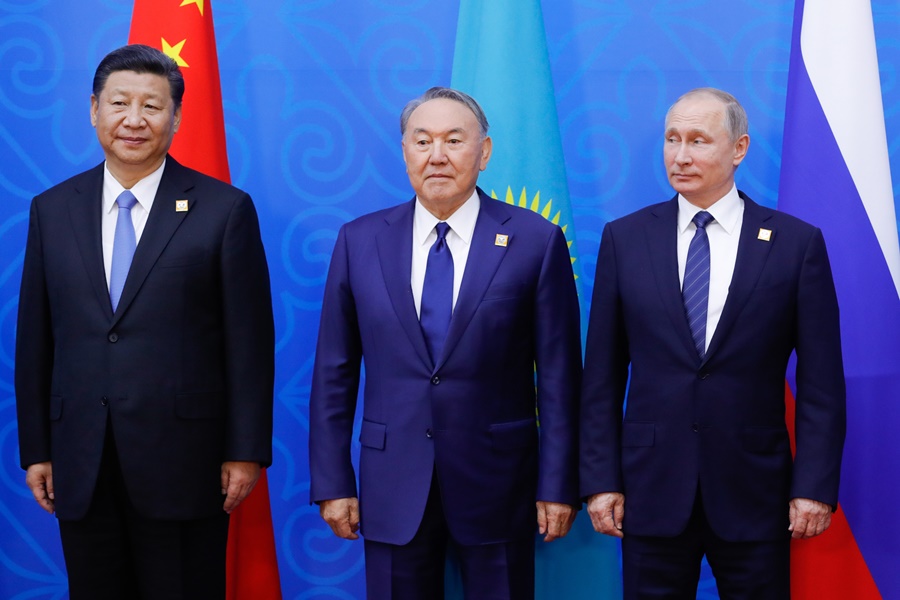

Presidents of China, Kazakhstan and Russia pose for a group photo after a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Heads of State Council on June 9, 2017. MIKHAIL METZEL / Getty Images

Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism has been gauged as largely successful. Astana has skillfully navigated relations with Russia and developed burgeoning ties with Beijing. It has remained the most reliable partner of the U.S. and an acclaimed partner of the countries in Europe. The Nazarbayev government has managed to sustain its multi-vector foreign policy orientation in the wake of the heightened political competition in the region unfolding against the backdrop of the divergent integration projects sponsored by the major players in Central Asia. Russia has been pushing for the Moscow-led integration, especially in the economic domain, through the Eurasian Economic Union, which was established in May 2013 and is comprised of Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Belarus, and Armenia. Beijing has been advancing its China-centric Silk Road Economic Belt project. Washington has not renounced its New Silk Road Initiative announced by the Obama Administration in 2011.

Kazakhstan has not been alone in its pursuit of balanced relationships with the major regional and global powers without discrimination or special privileges conferred on any of them. Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, among several other post-Soviet states, have proclaimed that multi-vectorism would serve as the guiding principle in their foreign policy conduct. No other state, however, has succeeded to date in the practical realization of the principle of multi-vectorism.

Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, among several other post-Soviet states, have proclaimed that multi-vectorism would serve as the guiding principle in their foreign policy conduct

The success of Kazakhstan’s multi-vector approach is certainly attributable to its ownership of valuable natural resources in high demand by other states. The overlapping energy dependences and interests of Kazakhstan, on one side, and Russia, China, and certain European countries, on the other, awarded the Nazarbayev government with an important trump in its relations with the regional and global powers that could be used for extracting concessions and spurring collaboration in the energy sector, as well as other areas of foreign relations. Furthermore, Kazakhstan’s strategic location as a gateway between Europe and Asia has been conducive to playing a balancing act between Russia and China. This unique intercontinental position has shaped Kazakhstan’s image as a “transcontinental economic bridge” between the West and the East and its identity as a Eurasian nation that, in turn, has helped to cement the state’s doctrine of multi-vector foreign policy.47

Kazakhstan’s energy resources awarded the Kazakh government with both capabilities and leverage in foreign relations, but it is the skillful diplomacy, personal ambitions and character of Kazakhstan’s longstanding president, and the health and robustness of state power institutions that put these capabilities to service of Kazakhstan’s interests and needs. The aptitude of the Kazakh government in navigating the overlapping and often conflicting interests of many global actors with considerable tact and skill has been an important factor in Kazakhstan’s achievements not only in its foreign policy, but also in fostering economic dynamism, opening capital markets, and encouraging the regional integration that has made this republic attractive as an economic partner.

Endnotes

- Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not an official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

- Roman Vakulchuk and Indra Overland, “Kazakhstan: Civil Society and Natural Resource Policy in Kazakhstan,” in Indra Overland (ed.), Public Brainpower: Civil Society and Natural Resource Management, (Cham: Palgrave, 2018), pp. 143-162.

- “Kazakhstan’s Key Energy Statistics,” Energy Information Administration, (2011), retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/country.php?iso=KAZ.

- Stephen Aris, “Russian-Chinese Relations through the Lens of the SCO,” Institut Français des Relations Internationales, No. 34, (2008), retrieved from https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Ifri_RNV_Aris_SCO_Eng.pdf; Erica Strecker Downs, “Sino-Russian Energy Relations: An Uncertain Courtship,” in James Bellacqua (ed.), The Future of China-Russia Relations, (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2010), pp. 146-175; Sherman Garnett, “Challenges of the Sino-Russian Strategic Partnership,” Washington Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 4 (2001), pp. 41-54; Nicklas Norling, “Russia and China: Partners with Tensions,” Policy Perspectives, Vol. 4, (2007), pp. 33-48; Bobo Lo, “China and Russia: Common Interests, Contrasting Perceptions,” Chatham House, (May 2006), retrieved from http://www.chathamhouse.org/publications/papers/view/108582; Shiping Tang, “Economic Integration in Central Asia: The Russian and Chinese Relationship,” Asian Survey, Vol. 40, No. 2 (March/April 2000), pp. 360-376.

- Elena Gnedina, “‘Multi-Vector’ Foreign Policies in Europe: Balancing, Bandwagoning or Bargaining?” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 67, No. 7 (2015), pp. 1007-1029.

- Until 2005, nearly all export pipelines transporting Central Asian fossil fuels traversed Russian territory. These included the Kenyak-Orsk pipeline, the Atyrau-Samara pipeline, a northbound link of the Russian Transneft distribution system, transmitting Caspian oil to Europe and the Central Asia-Center natural gas pipeline system controlled by Gazprom, which runs from Turkmenistan via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Russia. Russia holds the largest shares in the new oil Caspian Pipeline Consortium that was launched in 2001. See, Ardak Yesdauletova, “Kazakhstan’s Energy Policy: Its Evolution and Tendencies,” Journal of US-China Public Administration, Vol. 6, No. 4 (August 2009), pp. 31-39.

- Natural gas amounted to four percent in China’s “energy cocktail” in 2010, but its consumption is estimated to increase to ten percent by 2020. “International Energy Outlook 2010 - Natural Gas,” S. Energy Information Administration, (July 27, 2010), retrieved from http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/ieo/nat_gas.html.

- Richard Weitz, Kazakhstan and the New International Politics of Eurasia, (Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011), pp. 107-108.

- See, for example, Allen Lynch, “The Realism of Russia’s Foreign Policy,” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 53, No. 1 (2001), pp. 7-31; Jeffrey Mankoff, Russian Foreign Policy: The Return of Great Power Politics, (Washington, D.C.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009); Russia’s ongoing quest for a new modern identity has also given rise to a rich scholarship informed by constructivist assumptions. See, Ted Hopf, Social Construction of Foreign Policy: Identities and Foreign Policies, Moscow, 1955 and 1999, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002); Andrei Tsygankov, Russia’s Foreign Policy: Change and Continuity in National Identity, 3rd Edition, (Washington, D.C.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2013), and tenets of the English theory. See, Christopher Browning, “Reassessing Putin’s Project: Reflections on IR Theory and the West,” Problems of Post-Communism, Vol. 55, No. 5 (2008), pp. 3-13.

- For further discussion of the differences between offensive, defensive, modified structural, and neoclassical realism, see, Stephen Brook, “Dueling Realisms (Realism in International Relations),” International Organization, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Summer 1997), pp. 445-477; Randal Schweller and David Priess, “A Tale of Two Realisms: Expanding the Institutions Debate,” Mershon International Studies Review, 41, (May, 1997), pp. 1-33.

- Aris, “Russian-Chinese Relations.”

- Garnett, “Challenges,” pp. 41-54; Norling, “Partners with Tensions,” pp. 33-48; Lo, “Common Interests, Contrasting Perceptions.”

- Charles Zeigler, “Conceptualizing Sovereignty in Russian Foreign Policy: Realist and Constructivist Perspectives,” International Politics, Vol. 49 (2012), pp. 400-417.

- Aris, “Russian-Chinese Relations.”

- For example, Russia’s Transneft and China’s CNPC built the Skovorodino-Daqing oil pipeline as an extension of the West Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline, which became operational in January 2011.

- Tang, “Economic Integration in Central Asia,” p. 361.

- Jacqueline Braveboy-Wagner, “Opportunities and Limitations of the Exercise of Foreign Policy Power by a Very Small State: The Case of Trinidad and Tobago,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 23, No. 3 (September 2010), pp. 407-427.

- Brock Tessman and Wojtek Wolfe, “Great Powers and Strategic Hedging: The Case of Chinese Energy Security Strategy,” International Studies Review, 13, No. 2 (2011), p. 216.

- Reuls R. Hanks, “‘Multi-Vector Politics’ and Kazakhstan’s Emerging Role as a Geo-Strategic Player in Central Asia,” The Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3 (2009), pp. 257-267; Mikhail Molchanov, “Success and Failure of Multivectorism in Kazakhstan and Ukraine,” paper prepared for the ISA Annual Convention, (Montreal, Canada, March 2011).

- In international relations, wedging refers to a tactic of preventing or dividing another state’s (typically, an adversary or competitor) coalition with other countries.

- Yerzhan Kazykhanov, “Kazakhstan: 20 Years of Peace, Stability, Prosperity,” The Japan Times, (December 16, 2011).

- Pınar İpek, “The Role of Oil and Gas in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy: Looking East or West?” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 59, No. 7 (2007), p. 1188.

- Parag Khanna, “Surge of the ‘Second World,’” The National Interest, 119 (May/June 2012), p. 64; Michael Clarke, “Kazakhstan’s Multi-Vector Foreign Policy: Diminishing Returns in an Era of Great Power ‘Pivots’?” The Asan Forum, (April 9, 2015), retrieved from http://www.theasanforum.org/kazakhstans-

multi-vector-foreign-policy-diminishing-returns-in-an-era-of-great-power-pivots/. - Igor Tomberg, “Energy Policy and Energy Projects in Central Eurasia,” Central Asian and the Caucasus, 6, No. 48 (January 2007), retrieved from https://www.ca-c.org/journal/2007-06-eng/04.shtml.

- Clarke, “Kazakhstan’s Multi-Vector Foreign Policy.”

- Hanks, “Multi-vector Politics.”

- “China, Kazakhstan to Enhance Military-to-Military Cooperation,” Xinhua News, (December 2012), retrieved from http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-12/05/c_132021881.html.

- İpek, “The Role of Oil and Gas in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy.”

- İpek, “The Role of Oil and Gas in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy,” p. 1187.

- Vladimir Saprykin, “Gazprom of Russia in the Central Asian Countries,” Central Asia and the Caucasus, Vol. 29, No. 5 (2004), pp. 81-91.

- İpek, “The Role of Oil and Gas in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy,” pp. 1179-1199.

- Andrew E. Cramer, “Russia and 4 Other Nations Settle Decades-Long Dispute Over Caspian Sea,” The New York Times, (August 12, 2018), retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/12/world/europe/caspian-sea-russia-iran.html.

- İpek, “The Role of Oil and Gas in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy,” pp. 1179-1199.

- In 2008, Kazakhstan’s parliament approved legislation that authorized the government to make changes to any contract signed with other firms for extracting the country’s natural resources if these modifications were essential to Kazakhstan’s security and economic interests. The provisions of this legislation were incorporated into the 2010 Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan ‘On Subsoil and Subsoil Use.’ See, Kuanysh Sarsenbayev, “Kazakhstan Petroleum Industry 2008-2010: Trends of Resource Nationalism Policy,” Journal of World Energy Law and Business, Vol. 4, No. 4 (2011), pp. 369-379.

- İpek, “The Role of Oil and Gas in Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy,” pp. 1179-1199.

- Molchanov, “Success and Failure of Multivectorism in Kazakhstan and Ukraine.”

- Arthur Guschin, “China, Russia and the Tussle for Influence in Kazakhstan,” The Diplomat, (March 23, 2015), retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2015/03/china-russia-and-the-tussle-for-influence-

in-kazakhstan/. - Thrassy Marketos, “Eastern Caspian Sea Energy Geopolitics: A Litmus Test for the U.S. – Russia – China Struggle for the Geostrategic Control of Eurasia,” Caucasian Review of International Affairs, Vol. 3, No. 1 (January 2009), pp. 2-19.

- Weitz, Kazakhstan and the New International Politics of Eurasia.

- “Caspian Pipeline Consortium Marks the Groundbreaking for its $5.4 Billion Expansion,” Chevron, (July 1, 2011), retrieved from https://www.chevron.com/stories/caspian-pipeline-consortium-marks-

the-groundbreaking-for-its-5-4-billion-expansion. - “CPC Signs Agreement on Expansion Project,” Oil&Gas Eurasia, (January 2013), retrieved from http://www.oilandgaseurasia.com/news/cpc-signs-agreement-expansion-project; “Deal Signed to Expand Sino-Kazakh Oil Pipeline,” China Daily, (April 2013), retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-04/07/content_16379084.htm.

- “N. Nazarbaev: ‘Kitai - Krupnyi Torgovo-Ekonomicheskii Partner RK,’” kz, (February 2, 2011), retrieved from http://www.kursiv.kz/1195208184-kitaj-yavlyaetsya-krupnym-torgovo-yekonomicheskim-

partnerom-kazaxstana-nazarbaev.html. - “Zhongshiyou Jiang Kaifa Hasakesitan Wulihetao Gitian,” Guoji Ranqi Wang, (February 25, 2011), retrieved from http://gas.in-en.com/html/gas-0856085698941346.html.

- “Glavy Kazakhstana i Rossii Obsudili Ryealizatsiyu Strategicheskikh Sovmestnykh Proektov,” Novosti-Kazahstan, (March 17, 2011), retrieved from http://www.newskaz.ru/politics/20110317/1247234.html.

- “Nazarbaev: Kazakhstan Gotov Pustit’ Vsyu Svoyu Neft’ Cherez RF,” ru, (March 17, 2011), retrieved from http://www.bfm.ru/news/2011/03/17/nazarbaev-kazahstan-gotov-pustit-vsju-svoju-neft-cherez-

rf.html#text. - Molchanov, “Success and Failure.”

- Nursaltan Nazarbayev, “Vystuplenie Prezidenta Respubliki Kazakhstan N. Nazarbaeva na Mezhdunarodnoi Konferentsii “Strategiya Kazakhstan - 2030 v Dyeĭstvii,”’ kz, (October 11, 2005), retrieved from http://www.zakon.kz/65196-vystuplenie-prezidenta-respubliki.html; Kazykhanov, “Kazakhstan;” Weitz, Kazakhstan and the New International Politics of Eurasia, pp. 78-79.