Introduction

Long periods of instability often lead to fragmentation of political parties as a result of power struggles between them and, consequently, a lack of strong government. The lack of a strong government, in turn, results in a series of early elections and prolonged coalition talks, which further aggravate political instability. As the population’s confidence in the political process declines, guardianship regimes, which feed on popular distrust in politics, become centerpieces of the political system. In the end, if a country cannot amend its laws and constitution to address pressing problems, people start looking for a new system of government.

In Turkey, the search for a new system of government was motivated by economic and political crises, weak coalition governments, ineffective administrations and other problems associated with the parliamentarism. Coalition governments formed by political parties from different backgrounds, in particular, proved extremely unstable over the years and effectively brought the country to a standstill. To be clear, the lack of strong governments was closely related to the fragmentation of political parties as a result of parliamentarism and growing friction between various identity groups. During periods of instability, in turn, the weakening of political institutions made it easier for the military to overthrow democratically-elected governments and put democracy on hold.1

Two distinct political movements – Erbakan’s National Outlook and Türkeş’s Nationalist Movement – advocated presidentialism citing political unrest fueled by weak coalition governments and the crisis of authority

Over the years, the civilian-bureaucratic guardianship regime’s ability to exploit instability and gain control over the political arena rendered the consolidation of Turkey’s democratic institutions virtually impossible. Consequently, democratic consolidation proved elusive in the country, where politicians have been largely unable to develop long-term plans to promote democracy, even though the state of Turkish democracy improved under strong civilian leaders. In the end, it was Turkey’s failure to break the vicious cycle of guardianship and democratic consolidation that sparked a public debate on the need to change the political system in order to overcome the crisis of Turkish-style parliamentarism. Among the advocates of change, many came to support a transition to presidentialism.

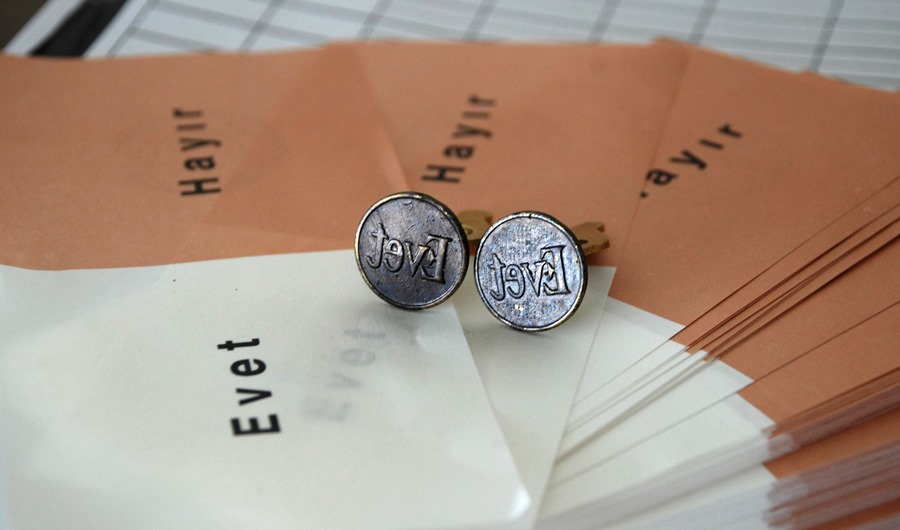

This study seeks to identify similarities between arguments used by advocates of presidentialism in recent decades. Having provided a short history of suggestions about presidential system, we primarily focus on the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) period, when the issue was debated more intensely and in greater detail than in the past. At the same time, we present the case made by successive generations of political transformation’s opponents. Finally, we talk about the background of Turkey’s most recent efforts to adopt a presidential system, including the cooperation between the AK Party and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) at the Parliament and the constitutional referendum, which will be held in 2017.

Political Transformation in Turkey and Its Reasoning: A Historical Perspective

The presidentialism debate in Turkey dates back to the 1970s, when political parties affiliated with the National Outlook (Milli Görüş) Movement –including the National Salvation Party (Milli Selamet Partisi, MSP) and the National Order Party (Milli Nizam Partisi, MNP)– made the case for constitutional reform. Accordingly, the MNP’s 1969 manifesto argued that “the president should come to power through single-round elections and the executive branch must be re-arranged in accordance with the presidential system to become more powerful and more effective.”2 The MSP’s 1973 election program, in turn, called for the adoption of presidentialism, single-round presidential elections and the unification of the head of government with the head of state: “The National Salvation Party is determined to create a democratic system of state, government and Parliament that is compatible with our national qualities and character. As such, a presidential system must be adopted,” the document read. “The presidency, or the head of state, will be merged with the prime ministry, or the head of government, to make the executive branch stronger, more effective and more swift. The nation shall elect the president through single-round elections. Consequently, the state and the people will naturally become united and integrated and there will be no room for domestic and international speculations, which wear down our regime over presidential elections.”3

In Nine Lights, Alparslan Türkeş, the MHP’s founder and long-time leader of the Nationalist Movement (Milliyetçi Hareket), argued that “strong and swift execution is only possible through the collection of executive power by a single individual. It is therefore that, in accordance with our history and tradition, we advocate the presidential system.” According to Türkeş, dividing the executive branch into two was “extremely problematic” because it would “weaken [executive] authority.” Making the case that the president and the prime minister should be merged into a single head of state, he reiterated his party’s commitment to “identify a single individual as the head of the executive branch” and proposed a plan to overcome Turkey’s political crises: “If our [idea], which we call the presidential system, is put to practice, the head of state shall be elected by the nation itself using the same method as a referendum. As such, a national democracy shall be established by making it possible for the people to participate in government and to get involved in decisions made [by the authorities] on issues of interest to themselves.”4

Turgut Özal emerged as a strong advocate of the presidential system in Turkey.Maintaining that the Turkish-style parliamentary system had stalled desperately-needed reforms, he argued that presidentialism –which he saw as a driving force behind change– was the best system of government for the country

In this sense, two distinct political movements –Erbakan’s National Outlook and Türkeş’s Nationalist Movement– advocated presidentialism citing political unrest fueled by weak coalition governments and the crisis of authority.

In the September 1980 military coup’s aftermath, the public debate on Turkey’s new constitution was dominated by supporters of presidentialism and semi-presidentialism. In particular, the discussion revolved around the introduction of direct presidential elections.5 At the time, many people were preoccupied with presidential elections because the Parliament’s failure to pick the next president after 115 rounds of voting had created a deadlock and subsequently paved the way to the coup d’etat. In the end, the discussion led nowhere because the 1982 Constitution’s authors designed the presidency as an ideological ally of the establishment that would protect the guardianship regime. Needless to say, the introduction of direct presidential elections would have ‘risked’ an individual, who did not share the military’s ideology, assuming the highest office in the land.

Four years later, the presidentialism debate made a comeback. Having won a landslide victory in the 1983 parliamentary elections, Prime Minister Turgut Özal’s Motherland Party (Anavatan Partisi, ANAP) experienced a 5-point setback in municipal elections held the following year. Fearing that the country was sliding back to coalition rule, Özal consulted with his closest advisors to see whether it was the right time to call for a presidential system.6 In order to avoid a confrontation with President Kenan Evren, the 1980 coup’s leader, he postponed his plans.

It was between 1988 and his death in 1993 that Turgut Özal emerged as a strong advocate of the presidential system in Turkey. Maintaining that the Turkish-style parliamentary system had stalled desperately-needed reforms, he argued that presidentialism –which he saw as a driving force behind change– was the best system of government for the country.7 Of course, Özal’s call for the adoption of presidentialism was supported by the argument that weak coalition governments could not rule Turkey in an effective manner. He added that the country’s diverse social fabric and the significance of politicians’ hometowns in Turkish politics inevitably fueled political fragmentation –a problem, he believed, only presidentialism could address. According to Özal, the presidential system was “more suitable for countries where multiple large ethnic groups [lived] together.” Imposing a parliamentary system on a diverse society, he feared, would fuel ethnic, religious and sectarian tensions and, along with politicians’ ties to their hometowns and regions, distract elected officials from public service.8

Özal not only explained why Turkey needed a presidential system of government but also presented a roadmap for the country. Noting that the introduction of direct presidential elections must not lead to a reduction of the president’s powers under the 1982 Constitution, he proposed that each president would come to power through two-round elections and serve two five-year terms. Furthermore, he called for presidential and parliamentary elections to be held simultaneously and demanded the president to run for re-election if the Parliament decided to dissolve itself and hold early elections.9

For Özal, the presidential system’s main selling point was the popular belief that coalition rule inevitably fueled political instability. In Turkey, a former empire with a diverse population, the parliamentary system rendered compromise impossible. In this sense, he believed that the country’s system of government ought to be compatible with its social fabric.10 In his statements about government reform, Özal frequently talked about the links between the unique historical experiences of European societies such as the power of monarchies and the emergence of parliaments. Recalling that Turkey was the successor state to a great empire, the Ottomans, he made the case for the adoption of American-style presidentialism. When his critics argued that the American-style presidentialism would lead to the country’s territorial disintegration through federalism, Özal responded by announcing that he was opposed to the creation of federal states.

Özal’s push for presidentialism was initially opposed by Süleyman Demirel, his biggest rival and chairman of the True Path Party (Doğru Yol Partisi, DYP), who would eventually change his mind and advocate constitutional reform. According to Demirel, Özal’s calls for the adoption of a presidential system reflected the ANAP leadership’s concerns over their declining popularity. When 65 percent of the people voted against a plan to hold early municipal elections in 1988, his attacks against Özal and his party became even more aggressive –partly because a presidential election was fast approaching. The DYP chairman’s argument was simple: The ANAP’s failure to hold municipal elections one year earlier than planned meant that his biggest rival had lost the people’s support. Under the circumstances, Demirel argued, it would have been wrong for an ANAP-dominated Parliament to select Turkey’s next president. To turn the odds in his favor, he proposed that the people, not parliamentarians, elect their president. In other words, Demirel had come out in support of direct presidential elections in an effort to prevent Özal from clinching the presidency with the backing of a Parliament with ‘no legitimacy.’ However, he repeatedly said that he did not support Turkey’s transition to presidentialism – mainly to distinguish his own position from Özal’s approach to political transformation.11

Three historic leaders of Turkish politics, Turgut Özal, Süleyman Demirel and Necmettin Erbakan, among others, also requested a presidential system for Turkey.| AA PHOTO

Three historic leaders of Turkish politics, Turgut Özal, Süleyman Demirel and Necmettin Erbakan, among others, also requested a presidential system for Turkey.| AA PHOTO

Having developed concrete proposals by mid-1989, Süleyman Demirel started drafting a constitutional reform bill to introduce direct presidential elections. Although the DYP-sponsored bill failed to receive the support of other political parties and, consequently, was never debated by the Parliament, Demirel’s plan remained an important item on Turkey’s political agenda ahead of the 1990 presidential election.12 In December 1990, the DYP leadership raised the issue of constitutional reform again at their party convention. Specifically, the party supported a system of government akin to semi-presidentialism, which they described as an ‘empowered presidency.’ Demirel’s proposal sought to grant the president with the power to call for referendums, dissolve the Parliament, shape foreign policy and identify national security priorities. The DYP leadership also maintained that governments should not have to receive a vote of confidence from parliamentarians, two-round elections should be introduced and the Parliament should become bicameral.13

Reactions to the proposed transition to presidentialism have always been shaped by political identities. Since politicians representing the periphery advocated presidentialism, elites have traditionally been opposed to change

Having charged Turgut Özal with ‘seeking to re-instate the sultanate’ for advocating presidentialism, Demirel, upon becoming president himself, rekindled the debate in 1997. “I have been residing at Çankaya [Palace] for four years and three months. During this period, I approved six governments. The situation inevitably raises questions about the merits of parliamentarism,” he noted. “If the Parliament cannot form a government, certain problems will arise and compel Turkey to look for alternatives such as semi-presidentialism and presidentialism –which are products of certain circumstances as well. What happens [under the two systems]? You move from a government elected by the Parliament to a government elected by the President.”14

Ironically, Demirel made the exact same arguments as Özal in his advocacy for presidentialism: “The presidential system is necessary to promote and maintain political stability. The executive and legislative branches must be separated. [Adopting] the presidential system is inevitable. [The Turkish people] should debate this proposal.” When faced with the criticism that presidentialism would pave the way to dictatorship, he argued that “the most concrete example [of the need to debate presidentialism] is the common misconception that the presidential system of government could lead to dictatorship.” To make such a claim, Demirel added, “one ought to be able to sufficiently analyze it –which is not being done.”15

The AK Party’s Reasons for Supporting the Presidential System

Following the AK Party’s rise to power and especially after 2005, the presidentialism debate rose to unprecedented prominence in Turkey. In 2007, the process of constitutional reform entered a new phaseas the presidential election was blocked by the Constitutional Court –which came to be known as ‘the 367 crisis.’ At the time, the establishment effectively ignored all precedents regarding presidential elections in order to prevent Abdullah Gül, the AK Party’s candidate, from assuming the presidency. During this process, the Parliament was forced into a deadlock– which was resolved when the AK Party, in cooperation with ANAP, passed aconstitutional reform bill to introduce direct presidential elections and a constitutional referendum was scheduled for October 2007. In the end, the people’s endorsement of proposed changes marked a turning point in the Republic’s history. Seven years later, when Erdoğan became Turkey’s first directly-elected president in August 2014, the country transitioned into de facto semi-presidentialism. However, it was seven years earlier that constitutional reform emerged as a necessity due to the risk of ‘dual legitimacy’ and ‘conflicts of jurisdiction.’

A political system becomes authoritarian in the absence of effective checks and balances. As such, whether a given regime is authoritarian or democratic is independent of parliamentarism and presidentialism

During the tenure of the AK Party and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, advocates of presidentialism supported their views with reference to the following: (i) The need to establish a new system of government in Turkey to avoid the re-emergence of political instability, which was a common problem in the past, (ii) Eliminating the risk of a return to weak coalition governments, which fueled political crises, rendered the political arena vulnerable, fragmented political parties and stalled the country’s democratic and economic progress under the parliamentary system, (iii) The removal of grey areas, which the guardianship regime and their supporters within the civilian/bureaucratic elite exploit, from the political arena and Turkey’s political culture, (iv) To address the problem of dual legitimacy in the political system, (v) Putting an end to political crises fueled by presidential elections, (vi) To strengthen the legitimacy of the executive branch by electing its head, (vii) Ensuring the consolidation and strengthening of democracy by upholding the people’s choices, (viii) The need to separate the executive branch and the legislative branch to increase the effectiveness and capabilities of both powers within their own domain, (ix) To strengthen the executive in order to expedite the decision-making process, (x) Promoting greater accountability for the executive branch by introducing direct elections.16

Routine Objections to Presidentialism

A closer look at the national conversation about the transformation of Turkey’s political system over the years would reveal that the same ‘routine objections’ have been voiced time and again out of prejudice. In other words, reactions to the proposed transition to presidentialism have always been shaped by political identities. Since politicians representing the periphery advocated presidentialism, elites have traditionally been opposed to change. As such, when certain politicians came out in support of presidentialism, other political figures and academics overwhelmingly targeted the plan’s supporters rather than the idea itself – the debate, in other words, was turned into a personal issue.

In this sense, when Özal, Demirel and Erdoğan endorsed presidentialism, opponents of the idea immediately claimed that they were trying to find a way to cling onto political power. Critics described Özal’s plan as ‘a personal endeavor’ and complained about his ‘unstoppable rise.’ Demirel’s statements about changing the system of government were discredited as an effort to perpetuate his presidency. Today, President Erdoğan remains the focal point of the ‘no’ campaign – at the expense of actual analyses of the content and framework of proposed changes.

Another cliché used by critics to discredit presidentialism is the discourse of ‘regime change’ – a thinly veiled reference to ‘the regime’s survival,’ a tool that was used by the elites to shape and reshape Turkish society and the political landscape over the years. This argument, which was made in the past to keep the population alert against perceived threats, continues to be used to mischaracterize the proposed changes in the country. When Demirel sparked the presidentialism debate, the Chairman of the Democratic Left Party (Demokratik Sol Parti, DSP), Bülent Ecevit, responded with the exact same argument: “I believe that proposals to facilitate regime change are a dangerous gambit. I don’t feel comfortable [with the idea]. The design that Demirel wants to promote represents the most rigid form of presidentialism in the world. The presidential system is the exact opposite of the parliamentary democracy that Atatürk founded. Personally, I believe that it entails some serious threats against the secular-democratic regime in Turkey. If [the president] attempts to overthrow secular democracy, who will stop him?”17 In 2016, the Chairman of the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP) Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of another leftist party, raised the exact same objection to the constitutional reform bill as DSP chairman Bülent Ecevit, another leftist figure, had eighteen years ago.18

A third line of argument used against the presidential system relates to the claim that Turkey’s political system will become more authoritarian and eventually give way to one-man rule if the country adopts presidentialism. In truth, a political system becomes authoritarian in the absence of effective checks and balances. As such, whether a given regime is authoritarian or democratic is independent of parliamentarism and presidentialism. The critics of Turkey’s transition to the presidential system, who like to complain about the risk of authoritarianism, conveniently avoid the fact that long-term instability caused by the parliamentary system resulted in the failure of Turkish democracy to consolidate. Furthermore, it is important to note that the clear definition of term limits, coupled with the requirement of a simple majority to win presidential elections, will steer the country’s political system further away from authoritarianism and expand the political center.

The president’s election by the people, in turn, created a problem of ‘dual legitimacy’ and paved the way for a power struggle between the president and the prime minister, both of whom were elected officials

Critics also like to fuel fears over Turkey’s territorial integrity by making the case that the presidential system would inevitably lead to the adoption of federalism and the creation of federal states. Often borrowing from the national conversation on the Kurdish question and exploiting the public’s sensitivities about the issue, the proponents of this view effectively claim that adopting a presidential system of government will lead to Turkey’s disintegration.

Of course, it is important to remember that not all presidential systems around the world are one and the same. Instead, critics almost exclusively concentrate on the United States and subject American-style presidentialism to selective interpretations while ignoring a number of countries where presidential and unitarism co-exist without any major problems.

Furthermore, critics falsely assume that the political system of another country will be imported to Turkey without any changes. They also ignore the fact that a country’s system of government isn’t necessarily related to its administrative system – whether it’s federal or unitary. A number of countries around the world have a parliamentary system of government and abide by the principle of federalism.

A final objection to the presidential system, which certain academic circles and policy experts voice, is directed at presidentialism as a system of government. In Turkey, the presidentialism debate often features reminders that, with the exception of the United States, countries that have adopted presidentialism experienced political instability and other problems – especially in Latin America. Among Turkish academics, it has become standard practice to make references to academic articles published in the early 1990s about problems related to the application of presidentialism in an attempt to discredit the presidential system itself.19 In fact, political scientists focusing on the perils of presidentialism20 and the virtues of parliamentarism21 must aknowledge that the problems weren’t related to presidentialism itself but to the transition of Latin American nations into unique versions of the same system of government.

Although some studies on the relationship between democratization and political regimes maintain that democratization occurs more effectively under parliamentarism than presidentialism, the progress made by countries with presidential systems over the years refutes their claims. The first systemic crisis, which resulted in the demise of democracies, took place following World War I in parliamentary democracies – which became consolidated again by the 1980s. By contrast, most democratic crises between the 1980s and the 1990s occurred in Latin America, where presidentialism remains more popular than parliamentarism. As such, the negative light shed on the presidential system over the past two decades largely reflects historical trends rather than the system of government itself.22 However, at this point, it is necessary to keep in mind that Latin American nations took major steps toward political stability, democratization and democratic consolidation in the post-Cold War period.

The Introduction of Direct Presidential Elections in Turkey

The presidential debate in Turkey has gained new momentum since 2007, when the people approved a plan to introduce direct presidential elections. At the time, the system of government had effectively changed and moved closer to semi-presidentialism. Under the 1982 Constitution, the president enjoyed greater powers than usually assigned to presidents in parliamentary systems. The president’s election by the people, in turn, created a problem of ‘dual legitimacy’ and paved the way for a power struggle between the president and the prime minister, both of whom were elected officials. While tensions could be kept under control in cases where both the president and the prime minister are members of the same political party, the crisis will inevitably deepen if the two offices are occupied by inviduals from different political backgrounds.23

It was therefore that the AK Party repeatedly called for the adoption of presidentialism over the past decade. As a matter of fact, Turkey’s largest party argued that the country needed a new constitution rather than just a new system of government. One of the most significant steps taken in this direction was the creation of an all-party parliamentary commission to facilitate dialogue on constitutional reform in 2011. The body, which featured three members from each political party, convened under the chairmanship of the Speaker of the Parliament for approximately two years. During the deliberations, the AK Party called for presidentialism as part of a broader effort to draft a new, civilian constitution. Rejecting this view, the CHP representatives maintained that the parliamentary system should be strengthened instead – a plan that echoed antiquated Kemalist principles in an attempt to preserve the status quo. While the MHP assumed a fiercely nationalistic position throughout the talks, the Peace and Democracy Party (Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi, BDP -the predecessor of HDP) delegation stuck to a discourse of Kurdish nationalism. By the time Speaker Cemil Çiçek announced in November 2013 that the parties failed to reach a consensus, the commission hadreached an agreement on just 59 articles and the AK Party’s proposal to debate the agreed-upon articles at the General Assembly was blocked by the rest of them.

In the referendum on the constitutional amendment which took place in 2007, 69 percent of the Turkish citizens voted for the President to be elected by the people. | AA PHOTO / BARIŞ GÜNDOĞAN

In the referendum on the constitutional amendment which took place in 2007, 69 percent of the Turkish citizens voted for the President to be elected by the people. | AA PHOTO / BARIŞ GÜNDOĞAN

Following the first direct presidential election in 2014, Turkey’s system of government effectively shifted to semi-presidentialism. On August 10, 2014, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan received 51.8 percent of the vote in the first round to become the country’s 12th president. On the campaign trail, Erdoğan had announced that, if elected, he would exercise all of his powers under the 1982 Constitution to serve as an ‘active’ president who would ‘guide’ the country as part of a ‘constructive’ mission.24 Upon assuming the presidency, he delivered his promise –which led many people to consider the proposed changes to the system of government as a necessity rather than a matter of choice.

Ahead of parliamentary elections on June 07 and November 01, 2015, the proposed transition into presidentialism became a centerpiece of the AK Party’s platform. On the campaign trail, the party leadership made the case that an executive presidency would thwart the risk of coalition rule and complete the guardianship regime’s elimination to maintain Turkey’s stability and strength. A commitment by the rest of the major political parties to reform the 1982 Constitution facilitated the establishment of another parliamentary commission following the elections. However, the commission was dissolved after failing to reach an agreement on ground rules.

Even though the AK Party had won the November 2015 election by a landslide, it did not control enough parliamentary seats to single-handedly reform the constitution. As a result, the ruling party sought to form an alliance with the opposition parties – whose representatives proved unwilling to even talk about presidentialism, giving the AK Party leadership no choice but to postpone their plans.25

In the wake of the failure of talks, both President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım warned that the parliamentary system would inevitably lead to crises between their offices and called for constitutional reform until a bloody coup attempt was orchestrated by FETÖ, a terrorist group led by Fetullah Gülen, on July 15, 2016. The illegitimate effort to overthrow Turkey’s democratically-elected government, which was largely seen as an attempted occupation of the country, was thwarted thanks to the sacrifice of ordinary citizens and members of the national security community with no ties to the coup plotters. The event, which was described by President Erdoğan as the beginning of “the second war of independence,” sidelined all other issues on the country’s political agenda, as the Turkish authorities concentrated on the fight against FETÖ.26

The similarities between the positions of the AK Party and the MHP, in particular, on July 15 fueled a new dynamism in the political arena

The attempted coup strengthened dialogue between various social and political groups by creating an atmosphere of compromise. At the same time, the fatal event encouraged major political parties to work more closely together. The similarities between the positions of the AK Party and the MHP, in particular, on July 15 fueled a new dynamism in the political arena. Meanwhile, the coup attempt raised awareness among politicians and the general population about threats against Turkey’s future. Finally, the coup attempt established that it was necessary to restructure the state in order to curb the influence of certain autonomous groups which had infiltrated the bureaucracy over the years.

It was under these circumstances that MHP chairman Devlet Bahçeli threw his party’s weight behind the AK Party government –which had been limited to counter-terrorism operations until then– and indicated that he would support a constitutional reform package which would change the country’s system of government. Addressing the MHP caucus at the Parliament on October 11, 2016, Bahçeli noted that there were certain problems with Turkey’s existing system of government and warned that these issues could evolve into serious political crises in the future. Arguing that the President’s decision to exercise his full constitutional authority had created a fait accompli, he stressed that the de facto situation should be formalized. The most striking part of Bahçeli’s speech related to the fact that Turkey had irreversibly changed on July 15 and the people were demanding a new social contract from their political leaders. Noting that all political parties had an obligation to address the people’s demands, the MHP leader said he would respect the popular vote on a series of constitutional reforms provided that the proposal did not violate his party’s ‘red lines’ – respect for the first four articles of the 1982 Constitution and the principle of unitary state. To be clear, Bahçeli’s reference to “the Turkish Republic’s fight for survival” in his historic address provided valuable insights into his reasons for seeking a compromise.

In Turkey, the search for a new system of government was motivated by economic and political crises, weak coalition governments, ineffective administrations and other problems associated with the parliamentarism

Upon receiving positive feedback from the AK Party leadership, Bahçeli stated four days later that his party would welcome “the submission of [the AK Party-sponsored] bill to the Parliament for review.”27 Shortly afterward, Prime Minister Yıldırım met Bahçeli at Çankaya Palace to discuss the proposed constitutional reform package. The leaders’ meeting led to a series of negotiations between AK Party and MHP delegations on a bill drafted by the ruling party’s policymakers. On December 10, 2016, the constitutional reform bill, which had been authored by the two parties, was formally submitted to the Parliament with the signatures of 316 AK Party parliamentarians. The bill, which was debated by the Constitutional Commission, was subsequently submitted to the General Assembly, where it cleared the 330-vote limit, and to the President for approval. Bahçeli announced that his party’s support for the proposed changes would not be limited to the Parliament and maintained that they would campaign in support of the proposed amendments.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

Turkey’s search for a new system of government dates back to the 1970s. Over the years, the parliamentary system’s shortcomings –political turmoil caused by coalition rule and political crises fueled by the president’s selection by parliamentarians, among others– have been the driving force behind the presidentialism debate. Furthermore, the fractured nature of political parties and clashes between identity groups resulted in political instability and facilitated the overthrow of democratically-elected governments by the military, which suspended democracy and shut down democratic institutions. Under the parliamentary system, the emergence of strong democratic institutions proved impossible, as political parties, which normally keep the political process going, have been reduced to passive by-standers in a severely-restricted political arena.

In recent decades, a number of political leaders called for a reform of Turkey’s system of government and the adoption of presidentialism in order to address pressing problems associated with the parliamentary system. The public debate, which was kicked off by Erbakan in the 1970s, was kept alive by Türkeş. While Özal came out in support of presidentialism in the late 1980s, Demirel made the case for constitutional reform in the following decade. The presidential system, which was backed by Erdoğan in the 2000s, became an important item on the nation’s political agenda following the introduction of direct presidential elections in 2007. Seven years later, the election of Turkey’s president by the people for the first time pushed the parliamentary system closer to semi-presidentialism.

In the aftermath of the July 15 coup attempt, which was orchestrated by FETÖ operatives, new possibilities of political compromise emerged – which the AK Party and the MHP utilize to jointly author a constitutional reform bill and pave the way to a referendum on the proposed changes to the system of government. Even though the bill refers to the proposed system as an executive presidency (cumhurbaşkanlığı sistemi) rather than presidentialism (başkanlık sistemi), its contents have been designed according to presidentialism. Judging by the constitutional reform bill itself, the authors appear to have taken two factors into consideration: First, the bill introduces certain changes to the system of government, which are unique to Turkey and were designed to avoid political crises that the country experienced in the past. Moreover, the new system builds on the experiences of other countries with presidential systems of government and learns from their solutions to systemic crises.

The constitutional reform bill successfully addresses the problem of ‘dual legitimacy’ by identifying the president as the head of the executive branch. Under the new system, the President is also expected to appoint deputy presidents, cabinet ministers and senior government officials as well as to oversee the establishment and abolishment of ministries and the identification of their duties and powers. At the same time, the 1982 Constitution’s clauses related to the non-partisan nature of the presidency are being amended to allow elected presidents to maintain their ties to a political party of their choice.

The constitutional reform bill also introduces changes to the structure and functioning of the Parliament. While the number of parliamentarians shall increase from 550 to 600, the minimum age to run for public office will reduced to 18. Presidential and parliamentary elections will be held every five years and at the same time. With the exception of the annual budget, the Parliament alone will exercise the right to introduce motions and bills. To avoid deadlocks due to political crises between the executive and legislative branches, the bill makes it possible for either the President or the Parliament to hold new elections for both offices. In other words, neither the executive branch nor the legislative branch will be able to dissolve the other without running for re-election themselves.

The most significant arrangement regarding the judiciary relates to the selection of the Board of Judges of Prosecutors. Whereas the justice minister and the justice ministry’s undersecretary are permanent members of the 13-member board, the President picks four of the remaining eleven members. Finally, the Parliament appoints all other members. Another important judicial reform is the abolishment of military courts.

Under the presidential system, the president’s right to issue executive orders, also known as decrees, will be subject to new regulations. The constitutional reform bill specifically indicates that the president cannot issue decrees regarding fundamental rights, privacy rights, political rights and obligations. Nor can the president sign executive orders regarding issues already addressed by law. If conflicts arise between presidential decrees and the laws, the latter take precedence. Consequently, if the Parliament passes a law on a subject addressed by a presidential decree, the decree becomes null and void.

Endnotes

- Ali Aslan, Nebi Miş and Abdullah Eren, “Türkiye’de Cumhurbaşkanlığı’nın Demokratikleştirilmesi,” SETA, No. 103 (August 2013); Ali Aslan, “Türkiye İçin Başkanlık Sistemi: Demokratikleşme, İstikrar, Kurumsallaşma,” SETA, No. 122 (April 2015).

- Milli Nizam Partisi: Program ve Tüzük, (İstanbul: Haktanır Basımevi), p. 10.

- Milli Selamet Partisi, 1973 Seçim Beyannamesi, (İstanbul: Fatih Yayınevi Matbaası, 1973), p. 17.

- Alparslan Türkeş, Dokuz Işık, (İstanbul: Bilgeoğuz Yayınları, 2015).

- Osman Balcıgil (Ed.), İki Seminer ve Bir Reform Önerisinde Tartışılan Anayasa, (İstanbul: Birikim Yayınları, 1982).

- “10 Yıllık Tartışma,” Sabah, (October 05, 1999).

- “Özal’dan Farklı Bakış,” Milliyet, (July 17, 1990).

- Mehmet Barlas, Turgut Özal’ın Anıları, (İstanbul: Sabah Kitapları, 1994), p. 141.

- “Özal Yeni Bir Türkiye Önerdi,” Milliyet, (November 30, 1990).

- “Başkanlık Sistemi Birleştiricidir,” Milliyet, (November 17, 1992).

- “Demirel’in Formülü,” Milliyet, (October23, 1998).

- “DYP Israrlı ANAP ‘Gelsin Görelim’ Diyor,” Milliyet, (April 07, 1989).

- “DYP, Topluma Yeni Bir Anayasa Sunuyor,” Milliyet, (November 20, 1990).

- “Türkiye, Başkanlık Sistemi ile Yönetilmeli,” Hürriyet, (September 19, 1997).

- “Demirel: Başkanlık Sistemi Tartışılmalı,” Hürriyet, (October 21, 1997).

- Nebi Miş, “Yeni Anayasa ve Başkanlık Sisteminde AK Parti’nin Yol Haritası,” Kriter, (November 2016).

- “Rejim Değişikliği Kumarı,” Milliyet, (May 28, 1998).

- “Kılıçdaroğlu: Rejim Değişikliği İsteniyor,” NTV, retrieved from http://www.ntv.com.tr/turkiye/

kilicdaroglu-rejim- degisikligi-isteniyorigOohTHY- EWBr3StKa8yxg. - Juan J. Linz and Arturo Valenzuela (Eds.), The Failure of Presidential Democracy: Comparative Perspectives, (Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1994).

- Juan J. Linz, “The Perils of Presidentialism,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1990), pp. 51-69.

- Juan J. Linz, “The Virtues of Parlamentarism,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 1, No. 4 (1990), pp. 84-91.

- Scott Mainwaring and Matthew S. Shugart, “Juan Linz, Presidentialism, and Democracy: A Critical Appraisal,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Temmuz 1997), pp. 449-471.

- Burhanettin Duran, “Bir Süreç Olarak Başkanlık Sistemi Arayışı,” Sabah, (May 26, 2016).

- Burhanettin Duran, “Cumhurbaşkanlığı Sisteminin Kurucu Misyonu,” Sabah, (December 02, 2016).

- Fahrettin Altun, “Şimdi Başkanlık Zamanı,” Kriter, (June 2016).

- “Erdoğan: 15 Temmuz Resmi Tatil Olacak,” Milliyet, (September 29, 2016).

- “MHP Genel Başkanı Bahçeli’den Başkanlık Sistemi Açıklaması,” Hürriyet, (October 15, 2016).