Making Sense of the “Post-American” Middle East amid Normalization

The Arab revolts dragged the Middle Eastern nations into separate camps that aggressively compete with each other. Whereas many countries, including Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq, evolved into weak players in a state of civil war, new axes of polarization emerged among the leading players –the Gulf, Israel, Egypt, Iran, and Türkiye– as a result of that process. As such, the current level of polarization exceeds the level that the United States’ invasion of Iraq introduced to the region in 2003. That chapter entailed the creation of an anti-democratic political domain, which resulted in a crackdown on popular demands, militarized ongoing conflicts by transforming them into civil wars, and caused the dominance of a reverse geopolitical wave that favored the status quo and authoritarian regimes. One of the most striking examples of that trend was Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s bloody coup in Egypt in 2013, which prevented elected governments from forming a new axis in the region.1 Later, the regionwide polarization between the Gulf and Iran, which dates back to 1979, emerged anew in the form of proxy wars. At the same time, polarization arose between the Gulf, Qatar, and Türkiye.

It is possible to argue that the Trump Administration’s Middle East policy (2016-2020) –which involved maximum pressure on Iran, strong support of Israel, and an attempt to unite the Gulf around a single axis– deepened both kinds of polarization. The impact of the Trump Administration, which facilitated rapprochement between Israel and the Gulf/Arab states, encouraged some countries to try and reshape the region. As those attempts at a new blueprint evolved into intense efforts to wear down opponents, the Gulf experienced tensions with Türkiye and Qatar, while countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, and Türkiye engaged in more fierce competition regarding questions of national security. As the Arab states were ideologically divided and thus weakened, Iran and Türkiye –two major players in the region– were compelled to concentrate on the Syrian crisis, which would continue for a long time. Meanwhile, competition between Saudi Arabia and Iran over the civil war in Yemen pushed the Gulf closer to Israel. That process, in turn, gave rise to the argument that Israel benefited most from the period of intense polarization in the aftermath of the Arab revolts.

While the tensions between various countries in the region, which were rooted in fierce competition, peaked in 2017 with the Qatar blockade,2 Joe Biden’s election victory in the U.S. encouraged the Middle Eastern states to make a new strategic assessment. The normalization process between Israel and the Arab states, which had been expedited by the Abraham Accords during Trump’s presidency, remained on track, as three new normalization trends emerged in the region. Accordingly, the Gulf and Qatar, the Gulf and Türkiye, and the Gulf and Iran tended to rely on diplomacy to end their disputes and manage existing crises.

The normalization process between Israel and the Arab states, which had been expedited by the Abraham Accords during Trump’s presidency, remained on track, as three new normalization trends emerged in the region

In this regard, “security on the basis of fierce competition” has been giving way to “linking security concerns to new pursuits of issue-based cooperation” in the Middle East. One could also argue that the multidimensional normalization attempts are rooted in a “post-American” realignment paradigm across the region. Indeed, Washington’s reduced interest in the region, coupled with Russia and China’s growing influence and the toll that competition has taken on the regional powers, have rendered new strategic assessments inevitable. In this sense, normalization attempts have emerged as the most important factor shaping the region’s geopolitical atmosphere in the short and medium terms.

Although it is impossible to predict the future course of this period of normalization due to persisting problems linked to the Arab revolts and traditional sources of instability, it goes without saying that a new regional architecture is in the making, which deserves some thought. It remains unclear what the distinguishing features of this new order will be and what exactly that means for the Middle Eastern political order.

Türkiye, in turn, has emerged as part of this new process of normalization and as a country that attempts to manage that process for a variety of reasons. After all, it is directly or indirectly involved in the distinct yet interrelated normalization processes that lay the groundwork for a new regional situation. That new state of affairs adds the idea of a new geopolitical consensus to Türkiye’s long-standing list of defense and security-oriented foreign policy parameters.

The Main Reasons behind Normalization

The primary reason behind the regionwide normalization process in the Middle East is the changing nature of the U.S.’ engagement with the region, which began during the Trump Presidency and has continued under the Biden Administration. Essentially, Türkiye and the rest of the regional players have made normalization attempts due to the direct and indirect reduction of U.S. involvement in the region. Indeed, the U.S. role and its military presence, which amounted to a security umbrella, and which peaked around the invasion of Iraq, has significantly decreased compared to the past.3 Whereas great powers like Russia and China appear to have most clearly benefited from the U.S. withdrawal, the truth is that the medium powers, too, are attempting to chart a new course in sync with that process.

In truth, Washington’s reduced influence over the region dates back to a choice that the Obama Administration made and by which the Trump and Biden Administrations have abided. It is a widely held belief among the American people and the American elite that the U.S. interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan have failed. Keeping in mind that both Democratic and Republican U.S. presidents campaigned on withdrawing from the Middle East, it is possible to conclude that Washington won’t revisit that decision. Indeed, the Asia-Pacific region remains at the top of the U.S. list of priorities. That does not mean, however, that the U.S. will ignore the delivery of hydrocarbon resources or the question of Israel’s security. At the same time, the U.S. has resorted to a comprehensive project of “delegating responsibility” in the region. Instead of engaging in costly interventions in the Middle East, Washington has adopted a strategy of power projection and course-setting through its allies in the region.4 Israel, the Gulf, Jordan, and Egypt are among those allies. In this regard, Washington’s support for the Abraham Accords between Israel and the Gulf as a model offers insights into its new policy toward the region. At this point, it appears that Washington is implementing a policy of deeper, more nuanced engagement with those nations with which it shares a common vision while retreating from the region. In other words, the U.S. withdrawal from the region is merely partial. Despite abandoning Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) amid Yemen’s civil war and pursuing a new nuclear deal with Iran, the U.S. has not totally lost its interest in the security of the Gulf. The presence of U.S. military bases across the Gulf attests to that fact. Again, the United States is inclined to maintain a military presence in those regions it perceives as low cost, as evident in its insistence on collaborating with the People’s Protection Forces (YPG), a component of the terrorist organization Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), in Syria. Due to Israel’s concerns over Iran’s growing influence and operations, it is possible that the United States will maintain an interest in the region –albeit in different ways. The level of that interest, however, appears to be too low to satisfy the perceived U.S. allies in the region, including Israel, the Gulf, and Türkiye. That dissatisfaction, in turn, encourages the regional powers to pursue normalization and engage in issue-based cooperation to ensure their national security. Whereas the Chinese presence in the region is considered likely to increase, it remains unclear how Russia will position itself in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine.

Despite abandoning Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates amid Yemen’s civil war and pursuing a new nuclear deal with Iran, the U.S. has not totally lost its interest in the security of the Gulf

The second driving force behind regionwide normalization is that the regional powers have become aware of the limits of their alliances with the great powers, as well as the shortcomings of their own ambitious power projections. The process of change, which the Arab revolts entailed, compelled the regional powers in the Middle East to engage in a challenging struggle to manage that process. Counting on their alliance with the U.S. and Israel, the Gulf states attempted to ensure that the new regional order would uphold the status quo, be anti-Iran and contain Türkiye. Those efforts, which could be described as the pursuit of a “regional design,” included weakening Iran in Lebanon and Yemen, where it posed a direct threat, rebuilding the Assad regime in Syria, forcing Palestine to reach a settlement with Israel, containing Türkiye with various instruments, and slowing down Gulf adversaries such as Qatar through economic and even military methods.

Yet the Gulf states, which engaged in such pursuits during the Trump’s presidency, could not reach their goals. Iran’s resistance, Türkiye’s combination of hard power and diplomatic activism, the Gulf’s insufficient capacity, and the lack of consistency between Trump’s strategy and the claims meant that the attempt to reshape the region achieved nothing more than deepening the chaos.5

The failure of those projects, which the regional powers implemented in cooperation with the great powers, led them to reposition themselves to reconcile, cement their gains and strengthen their security and defense sectors. Whereas almost all nations have prepared for or assessed realignment, the UAE and Türkiye have been the leading players on that front. Having made those general points, it would be useful to inspect each of the four normalization processes more closely.

This study first analyzes the period of “polarization and design efforts” that laid the groundwork for normalization trends in the region. Second, it points out that the pursuit of normalization occurred due to the regional powers realizing the limits of their own power against the backdrop of changes in the international system and the new U.S. administration’s policy choices. Third, it assesses the four distinct normalization processes in the region. The fourth point will be to analyze Türkiye’s path to normalization and the current state of that endeavor. Last but not least, it focuses on the problems with and the limits of regional normalization, and what lies ahead in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Anatomy of Four Normalization Attempts

It is possible to argue that there are four normalization attempts underway in the Middle East –each with its own dynamics and processes. The Abraham Accords, which were shaped by the Trump Administration’s policy toward Iran and Israel, represent the first such attempt. Originally designed to establish an American-backed pact between the Gulf states and Israel to oppose Iran, the Accords went further. Indeed, the relevant agreements amounted to a radical shift in the Arab states’ long-standing anti-Israel and pro-Palestinian policies.

UAE Air Force Aerobatic Team performs a demonstration flight during the visit of Turkish President Erdoğan to Abu Dhabi, UAE, on February 14, 2022. UAE Air Force / AA

UAE Air Force Aerobatic Team performs a demonstration flight during the visit of Turkish President Erdoğan to Abu Dhabi, UAE, on February 14, 2022. UAE Air Force / AA

As the regional competition that emerged out of the Arab revolts encouraged the Arab states to focus on their security issues, the international system shifted away from a situation where Israel could be pressured into implementing a two-state solution in Palestine. Moreover, Trump’s decision to move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem and to raise the issue of the Deal of the Century (albeit without success) further reduced the importance Arab leaders attached to the Palestinian question.6 At this point, the Israeli government developed its relations with the UAE and Bahrain as well as Sudan and Morocco, which got on board at a later point in time. Meanwhile, it is no secret that Saudi Arabia and Egypt, as the region’s primary players, are among the de facto supporters of the process to constrain Iran.7 It is obvious that the harsh sanctions Trump imposed on Tehran in line with his administration’s “maximum pressure” policy upon withdrawing from the nuclear deal did not yield results. Tehran refused to quit, and Trump ended up losing the election. Consequently, the Gulf states opted to de-escalate tensions in their bilateral relations with Iran.8

The second normalization process –often described as “intra-Gulf normalization”– originated in al-Ula Summit. That process relates to the end of the blockade that Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain had imposed on Qatar, which reached its peak in 2017. The Turkish support to Qatar, which amounted to preventing a coup d’état in Doha, led to the blockaders giving up on their severe demands. Partly due to the changing circumstances in the region, it was possible for both sides to reach an agreement without looking like victors or losers. Qatar’s autonomous and exceptional position within the Gulf thus landed on a permanent footing and came to be viewed as a legitimate position by other countries in the region. It would be difficult, however, to argue that the crisis of confidence between Qatar and the other Gulf states, which is rooted in the blockade, has ended or that the pre-blockade status quo has been restored.

Another important normalization process, which is quite relevant to the Gulf region, remains underway between Iran and the Gulf –albeit more cautiously. Since Iran views the Persian Gulf as a “Persian” Gulf, it seeks to position itself as the obvious leader there.9 Countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain (which pushed for an “Arab” Gulf) consider the Iranian influence a grave threat. Despite persisting tensions, there are notable signs that the situation continues to de-escalate. Indeed, Riyadh and Tehran have already launched exploratory talks. Meanwhile, the UAE, as the most pragmatic Gulf state, has revived a functional relationship with Iran at a senior level.10

The final normalization process in question has been pioneered by Ankara. Since early 2021, Türkiye has pursued comprehensive yet cautious normalization with the UAE, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, with which it has experienced major tensions in recent years. That process, which has occurred on a bilateral basis, has led to significant progress with the UAE in terms of cooperation regarding investments and the defense industry. At the same time, high-level visits have taken place with Saudi Arabia and Israel as a reflection of the commitment to start a new chapter in bilateral relations. By contrast, the normalization process between Türkiye and Egypt has yet to go beyond meetings among intelligence and security officials. While normalization with Saudi Arabia is expected to gain momentum in the near future, Türkiye approaches its rapprochement with Israel much more cautiously. Specifically, the government of Naftali Bennett is threatened by a comeback from the former Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. At the same time, the actions of far-right Jewish groups regarding Jerusalem, the al-Aqsa Mosque, and Palestinian rights render the process between Tel Aviv and Ankara more fragile.11

While normalization with Saudi Arabia is expected to gain momentum in the near future, Türkiye approaches its rapprochement with Israel much more cautiously

Although those four normalization processes, which were molded by a variety of factors, face the risk of suspension or derailment, there is reason to believe that they will stay on track. After all, the regional powers assess that normalization serves their interests in the new international geopolitical environment in which the U.S. strategic priorities in the Middle East have changed and the global power struggle is gaining momentum. At a time when the Russian attempt to invade Ukraine has revived the discourse of the ‘cold war’ and the ‘third world war’ anew, it is possible to think that attempts to repair bilateral relations shall take place on a clearer strategic basis. Indeed, Türkiye appears to have charted a new course for diplomacy due to reduced threats in its military and security perceptions, as the other regional powers seem eager to become part of the geopolitical momentum caused by Türkiye’s changing regional role. However, one cannot disregard the fact that the conflicting aspects of those four-normalization process could still create a new atmosphere of competition.

The Course of Normalization Experiments

The four normalization experiments in the region follow different courses. The first process involves Israel and the Arab countries and originated in the Abraham Accords,12 which have notably shaped the region’s political discourse for the last three years. That process, which was backed by Trump, Netanyahu, and the UAE, has already evolved into comprehensive cooperation between the Gulf and Israel. It is possible to see that the Abraham Accords, which were originally depicted as anti-Iran, represent a region wide change that won’t stop there. Instead, it is about making public the long-standing, secret relationship between the Gulf states and Israel and establishing a platform for cooperation. At the same time, those agreements ostensibly give the upper hand to the UAE and Israel in terms of their regional ambitions. The Abraham Accords, which improved Israel’s bilateral relations with the Arab parties, appear to have undermined the causes of Palestine and Jerusalem vis- à-vis the Arab people. Indeed, the Accords, which did not prevent Israel’s establishment of new settlements, did not entail any benefits for the Palestinians.13 Again, that process not only strengthened Israel vis- à-vis Iran; those agreements, which helped Tel Aviv break its isolation in the region, ironically made an indirect impact on the slow progress of normalization between Israel and Türkiye.

The second normalization process in the Middle East has been taking place within the Gulf Cooperation Council.14 The main developments in the Gulf include Qatar’s shift away from an attempt to reshape the region around Saudi Arabia and the UAE, its support for political forces that were inspired by the spirit of the Arab Spring, and its decision to improve its relations with countries like Iran and Türkiye. However, the Gulf’s “traditional” powers punished Qatar for pursuing an “alternative foreign policy” through the 2017 blockade. That country, however, foiled a coup attempt with Turkish support, rendering the blockade effectively meaningless, as the partial U.S. withdrawal from the region encouraged the Gulf states to start cooperating once more.15

In the end, the al-Ula Summit of 2021 marked the conclusion of four years of crisis in the Gulf. Accordingly, Saudi Arabia and the UAE essentially made peace with Qatar’s pursuit of a different foreign policy and conceded that the Gulf could no longer promote a singular worldview or foreign policy projection. The friendly photos of Sheikh Tamim, the Emir of Qatar, and the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, the lifting of a ban on Qatar-funded news channels like Al Jazeera in the Gulf, and the restoration of al-Ula process.16

Notwithstanding these developments, the relationship between Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE would best be described as a “cold peace.” After all, Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Doha approach the Middle East with different worldviews and policy choices. Indeed, the al-Ula Summit may have ended tensions between the Gulf states, but it also confirmed that their differences over policy were permanent. That the Gulf states no longer have a common vision for the region is manifested by the disagreements between Saudi Arabia and the UAE over the situation in Yemen. Likewise, the UAE spearheaded the Abraham Accords (in which Saudi Arabia was not involved) and Qatar preserves its unique position. Even though the intra-Gulf competition is currently confined within normalization, the situation that preceded the Qatar blockade has not been restored. Keeping in mind the Gulf states’ ever-growing human capital, diversifying economic portfolios, and increasingly ambitious foreign policy goals, one would conclude that the ‘normalized’ Gulf region is in an ideal position for competition.

The al-Ula Summit may have ended tensions between the Gulf states, but it also confirmed that their differences over policy were permanent

The third normalization process in the region continues between Iran and Saudi Arabia, which suspended their diplomatic relations in 2016, when an attack on the Saudi Embassy in Tehran17 took place in response to the execution of a Shiite cleric in the Kingdom, causing a rupture in bilateral relations. Over the last six years, Riyadh and Tehran (which pursued different policies after the Arab Spring anyway) have been involved in a cold war with an impact on various conflicts across the region. It is possible to identify Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen as the main sites of competition through proxies. Obviously, the most serious power struggle remains underway in Yemen. Indeed, both governments make an effort to ensure the survival of their respective worldview and keep their sectarian identity alive in such areas of competition. On occasion, the competition through proxies ends up targeting one of the sponsor countries. Cross-border attacks by the Iran-controlled Houthi groups against Saudi Arabia from Yemen immediately come to mind.18

From Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy perspective, Iran represents a very serious question of regime security that is difficult to address. Tehran’s post-1979 pursuit of expansionist goals under its ‘resistance policy,’ its attempts to export its regime and revolution to other countries and its establishment of a large network of armed groups for that purpose pose a critical challenge to Riyadh. The existence of a Shia minority in Saudi Arabia and that the Saudis keep stumbling on Iran in places like Yemen and Lebanon (where they want greater influence) are among the main factors that inform Riyadh’s foreign policy universe. As such, Saudi Arabia strongly supported the Trump Administration’s decision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal and its adoption of the ‘maximum pressure’ policy. The Kingdom viewed that approach as an opportunity to isolate Iran in the international arena and to actively combat Iranian expansionism. That is how the relevant nations formed an alliance around the now-famous orb that was established during Trump’s first abroad visit as the U.S. president.

That alliance morphed into an attempt to reshape the region to contain Iran, as a priority, and, to some degree, Türkiye. Yet Trump’s sanctions against Iran failed to yield results. Furthermore, the Biden Administration’s arrival in 2020 compelled Saudi Arabia and those Gulf states with which it collaborated to revise their policy of escalation with Iran. The following year, Iraq hosted a series of meetings between Iranian and Saudi officials for the purpose of establishing a framework for normalization.19 Even though those talks have yet to yield results, the two governments are actually talking to each other signals that their foreign policy development process has changed. Indeed, the United States, which partly withdrew from the region, and Joe Biden, who keeps Saudi Arabia at arm’s length due to the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, appear to have left Riyadh alone in its efforts to counter Iran’s influence. That new state of affairs apparently encouraged the Kingdom and the UAE to pursue normalization with Türkiye and Iran alike. It is likely that Iran will take fresh steps to strengthen its regional influence if it successfully signs a nuclear deal with the Biden Administration. Iran’s attempts to fill the power vacuum that Russia left behind in Syria due to the war in Ukraine with its Shia militias attest to that fact.20

Saudi Arabia, which does not wish to confront Iran without U.S. security guarantees, aims to bolster its defense industry by cooperating with Türkiye. It also seeks to de-escalate tensions over the civil war in Yemen by repairing its relations with Iran. Nevertheless, the ideological, cultural, and sectarian aspects of the competition between Saudi Arabia and Iran continue to impose certain limits on the normalization process. As such, it seems realistic to expect normalization between Tehran and Riyadh to be slow and fragile.

Türkiye’s Path to Normalization

Among the normalization trends in the Middle East, the last one, specifically Türkiye’s pursuit of normalization with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Egypt has been the most comprehensive and the most influential over the other processes. The Turkish policy of normalization represents an attempt to turn over a fresh leaf in bilateral relations with multiple states. Since some of the problems that the post-Arab Spring policies created for countries in the region have since disappeared, and other problems have created a new status quo, the normalization talks between Türkiye and the relevant nations did not require any party to leave aside their respective national interests. Quite the contrary, it was enough for those players to make new strategic assessments about their circumstances and to conclude that they could just go down that path to consolidate their national interests. Türkiye’s recent military activities in the Middle East, the Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Eastern Mediterranean supported, rather than undermined, its diplomatic efforts amid normalization.

Türkiye’s recent military activities in the Middle East, the Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Eastern Mediterranean supported, rather than undermined, its diplomatic efforts amid normalization

In this regard, Türkiye adopted a policy of hard power as well as a policy of normalization in an attempt to respond to emerging power vacuums in its neighborhoods. In other words, those changes in policy were not informed by ideological pursuits.21 Instead, they aimed to cope with certain threats, including the refugee wave, terrorism, and proxy wars, and represented policy choices that took into consideration the changing priorities of the time and the relevant players. Indeed, during the Arab Spring, Türkiye threw its weight behind elected politicians to oppose the military coup in Egypt. Yet the country’s rhetorical critique of the coup never evolved into a policy akin to “democracy promotion.” Likewise, Türkiye was the last country to intervene in Syria in 2016, despite having dealt with problems like terrorism and refugee waves for some time. The purpose of that intervention was to eliminate the PKK-YPG’s “terror corridor” and to establish a safe zone for Syrian refugees.

Türkiye’s national interests, which are pursued in a multi-dimensional setting, are far too complex and dynamic to be reduced to any specific ideological preference or bloc. Countries like Russia became aware of that fact and have successfully worked with Türkiye despite strategic disagreements.

Another factor that has encouraged the countries in the region to consider normalization with Türkiye is the progress of that country’s defense industry –specifically armed unmanned aerial vehicles (aka drones)– and its resulting success in theaters like Syria, Libya, Karabakh, and Ukraine. Having experienced the negative impact of fierce competition with Ankara, the region’s governments came to require Turkish assistance to beef up their defense and ensure their safety from Iran, with which the U.S. aims to conclude a nuclear deal.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s leader-to-leader diplomacy also plays a crucial role in Türkiye’s management of the normalization process. His leadership was key to starting that process on the back of intelligence-to-intelligence talks, determining its scope and setting its pace. Another important point is that Türkiye’s normalization attempts focus on repairing bilateral relations rather than acting as part of a pact or other collective entity.

That repair process undoubtedly paid off quickest with the UAE. That process, which could be analyzed as normalization at the top level, achieved a high level of clarity thanks to the proposed solutions, as the process of repair was completed within a short period of time.22 Due to a visit by Mohammed bin Zayed, then crown prince of the UAE, to Ankara on November 24, 2021, and President Erdoğan’s February 14-15, 2022 visit to Abu Dhabi, the Türkiye-UAE normalization process appears to have made significant progress. In addition to their trade relations, which remained relatively unharmed amid tensions, political cooperation and security/military coordination have been among the main components of Türkiye-UAE relations. Having left behind escalation and competition in the aftermath of the Arab revolts, the two nations adopted a flexible and pragmatic approach to foreign policymaking and made a firm commitment to repairing their relationship, –which caught the attention of all the other players.

It remains to be seen how the quick recovery of Türkiye’s bilateral relations with the UAE will impact their approaches to the problems in the broader Middle East; it goes without saying that the two nations will continue to have different takes on regional issues. Nevertheless, they are inclined to avoid confrontation and to work together in places like Libya, Syria, and the Horn of Africa, where they used to compete. In other words, Ankara and Abu Dhabi not only repaired their bilateral relations but also cleared the path to new partnership opportunities in many strategically important areas. As a result of normalization, the perspectives of both nations on the Horn of Africa and Libya have already tended to align.

Another country that Türkiye included in its normalization agenda through leader-to-leader diplomacy is Israel. Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s visit to Ankara on March 9, 2022, marked the beginning of a new chapter in bilateral relations, characterized by de-escalation, after more than a decade. During Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu’s visit to Israel and Palestine on May 24-25, 2022, the two governments agreed on gradual normalization.23 Both Ankara and Tel Aviv continue to make an effort to ensure that the normalization process, in which the Israeli side engages cautiously due to domestic political concerns, proves resilient. It would seem that the two nations have agreed to identify their differences, require the involvement of their leaders for crisis management and adopt an approach that would not jeopardize their relations with third parties. A case in point involves the tensions Israel made the Palestinians experience during Ramadan 2022 over the al-Aqsa Mosque. During that period, President Erdoğan spoke with his counterpart, President Herzog, to end the violence. That incident both put the Turkish-Israeli normalization process to the test and demonstrated that Erdoğan is pursuing normalization with Israel without necessarily disregarding Türkiye’s policy toward Palestine. 24

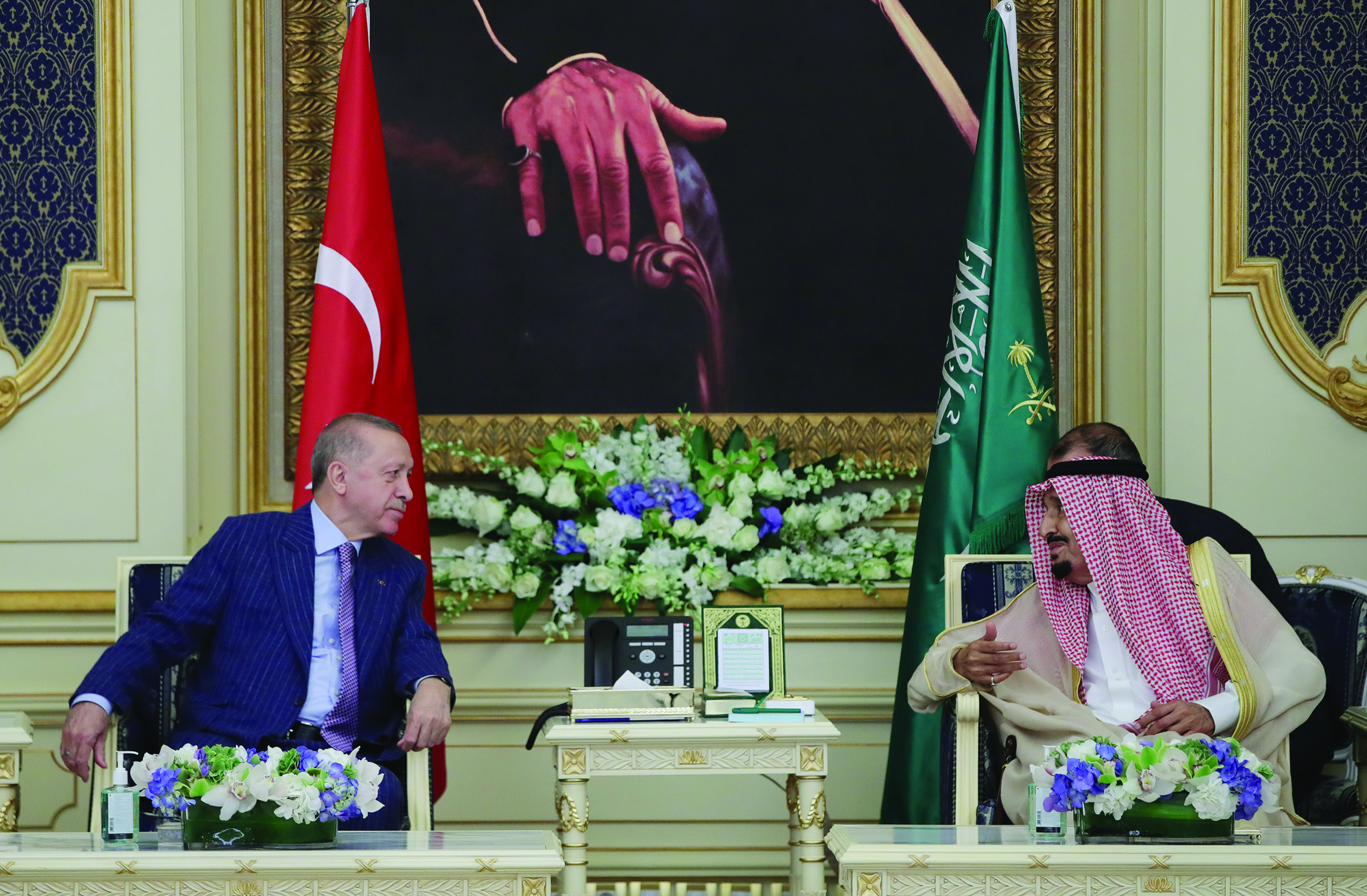

Turkish President Erdoğan meets King of Saudi Arabia al-Saud at al-Salam Royal Palace in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on April 28, 2022. MURAT KULA / AA

Turkish President Erdoğan meets King of Saudi Arabia al-Saud at al-Salam Royal Palace in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on April 28, 2022. MURAT KULA / AA

Indeed, Ankara supports Palestine independently of the normalization process. Furthermore, the Turkish government endorses a two-state solution, criticizes Israel’s policy regarding the settlements, and remains vocal about the status of Jerusalem and the al-Aqsa Mosque. It requests that the rights of Palestinians, who were forcibly removed from their homes in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood last summer, to be protected. It is obvious that crisis management, together with an active and positive agenda, is needed to ensure that tensions related to the Palestinian question do not hinder the normalization process. Meanwhile, Israel chooses not to weaken its relationship with Greece against the backdrop of normalization with Türkiye. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify the following developments as facilitating normalization: the end of Türkiye’s exclusion from the Eastern Mediterranean, Washington’s decision to stop supporting the EastMed pipeline project, and Türkiye ’s growing importance vis-à-vis the delivery of energy to Europe due to the war in Ukraine.

Speaking of energy, although the natural gas discovered in the Leviathan field is apparently enough for Israel and its engagement with neighboring countries, energy cooperation between Türkiye and Israel remains an important agenda item due to opportunities that it could create in the medium- and long-term. Iran’s growing influence in the region is among the issues that Ankara and Tel Aviv shall discuss among themselves. The likelihood of Iran filling the power vacuum that Russia leaves behind, and of Iran adopting more ambitious policies in light of the nuclear deal are among the main reasons behind Tel Aviv’s rapprochement with Ankara. Türkiye, whose bilateral normalization attempts are not intended to antagonize any third party, should be expected to play a more active balancing role in the region.

Saudi Arabia is the third country on Türkiye ’s path to normalization. A new chapter began in that country’s bilateral relations with Türkiye once the Khashoggi trial, a key source of tensions between the two nations, ended. (Saudi Arabia had been asking Türkiye to hand over the case to Riyadh, where the perpetrators would be held accountable.) On April 28-30, 2022, President Erdoğan visited the Saudi capital and met with both King Salman and the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to clear the path to cooperation in bilateral relations and on a regional scale. Reviving trade (which had declined due to Riyadh’s decisions) and promoting partnerships in the defense industry were also on the agenda. The two major regional powers could potentially reposition themselves and work together on Syria, Palestine, Iran, and a range of other issues.25

It is possible to argue that Türkiye and Saudi Arabia ended up needing each other more to promote stability in the Middle East and create a new order following the partial U.S. withdrawal from the region. Whereas Türkiye remains compelled to establish a safe zone for refugees in Northern Syria and combat the YPG, Saudi Arabia is unhappy with the current state of the war in Yemen and attacks by the Houthis. It goes without saying that Iran’s expansionist policy encourages Riyadh to take an interest in Ankara’s robust defense industry with an eye to its own national security. Riyadh, whose relationship with the Biden Administration remains tense, has witnessed an uptick in its hydrocarbon revenue thanks to the war in Ukraine. Having launched a development drive in line with its 2030 Vision, the country competes with Abu Dhabi on that front.

It is possible to argue that Türkiye and Saudi Arabia ended up needing each other more to promote stability in the Middle East and create a new order following the partial U.S. withdrawal from the region

Furthermore, normalization between Türkiye and the Kingdom is significant enough to impact the remaining Gulf states. That process should be expected to promote stability by improving trade relations and facilitating security-based rapprochement. It is particularly important to note that normalization between Türkiye and the Gulf states, which has replaced tensions with cooperation, has the potential to counter-balance Iran.26

The final part of Türkiye’s policy of regionwide normalization relates to Egypt. It is important to bear in mind that the two governments have experienced a significant loss of trust since 2013. In this regard, it was not unexpected that both sides would adopt a cautious stance toward normalization and that this process would move forward more slowly than the rest. Specifically, the Turkish-Egyptian normalization process has not been expedited by leader-to-leader diplomacy. Normalization between Türkiye and Egypt has not featured a rapprochement akin to that of the UAE and Saudi Arabia; it has rather relied on intelligence agencies and diplomats. Although the Muslim Brotherhood’s continued presence in Türkiye is among the subjects of negotiations for repairing the relationship, which was derailed by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s coup, Cairo’s eagerness to take into consideration many factors and its decision to play for time has thus far prevented the start of a new chapter in bilateral relations.

Normalization between Türkiye and Egypt has not featured a rapprochement akin to that of the UAE and Saudi Arabia; it has rather relied on intelligence agencies and diplomats

It would seem that Cairo does not want to undermine its relationship with Athens, which it strengthened in recent years. However, normalization between Türkiye and Egypt could potentially make an impact on the regional balance of power. An important Arab country that isolated itself from the world in recent years, Egypt could take the lead in the Eastern Mediterranean, Libya, North Africa, Syria, and Palestine. If Türkiye (which already has a delimitation agreement with Libya) were to conclude a similar agreement with Egypt, it would likely cause Greece to abandon its maximalist demands. After all, those same demands happen to hurt the interests of Libya, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and Palestine. Indeed, finding a just solution to pressing problems in the Eastern Mediterranean would certainly de-escalate tensions between Türkiye and Greece as well as the European Union. By contrast, Egypt’s failure to participate in the regional normalization process prevents it from playing a balancing role in regional crises and competition.

Normalization between Türkiye and Egypt could potentially make an impact on the regional balance of power

Conclusion: The Limits and Future of Normalization

The Arab Spring undermined the traditional order on the national and regional levels, exposing the Middle East to pressure for comprehensive change for more than a decade. Following a lengthy period of conflict and competition, all countries in the region began to pursue a period of regionwide softening. The agenda of normalization is being implemented on the basis of certain issues in many parts of the Middle East in a coordinated manner. The areas that this trend affects most intensely include the Gulf, Israel, and Türkiye. The various processes of normalization, which continue independently of one another, actually establish a regional pattern. At the same time, they represent a precursor to potential stability in the post-American Middle East, which continues its search for clarity. It is inevitable for the partial retreat of a superpower from the region to encourage the existing middle powers to pursue fresh balancing. It is apparent that the remaining regional players, including Türkiye, have embraced a comprehensive pursuit of normalization in response to that inevitability. It would be more accurate, however, to describe that process of normalization as the zeitgeist of regional politics for the short- and medium-term, rather than a trend toward forming pacts or security-based partnerships. In the aftermath of a conflict-heavy decade, the region currently yearns for policies that build on peace and quiet.

It is important to highlight the crucial role of Türkiye, which acts in line with the spirit of normalization in the region, vis-à-vis all such developments. In this regard, decision-makers in Türkiye subscribe to a new model that will set the tone for that country’s relations with the Middle Eastern states over the coming years, rather than focusing on short-term interests or quick economic gains. In line with the paradigm ushered in by the Arab Spring, Türkiye adopted a policy that attaches importance to popular demands and opposes military coups across the region. That choice entailed obligatory tensions with certain established political entities that favored the status quo, including the Gulf monarchies and Egypt. At this stage, where the notion of the Arab Spring has lost its importance, however, it is perfectly natural for Türkiye to try and rehabilitate its relations with many nations. In this regard, normalization has become the main component of the foreign policy development process. At a time when the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan are normalizing their relations with Israel, tensions are de-escalating among the Gulf states and the regional players prepare for the post-American period, Türkiye, too, is pioneering normalization in an attempt to defend its national interests. The normalization processes, which occurred relatively quickly with the UAE and Saudi Arabia and more cautiously with Israel, sheds light on Ankara’s relations with other nations in the region as well. Normalizing bilateral relations with those countries with which Türkiye competed in the past, whether openly or in a veiled manner, through compartmentalization and an emphasis on potential areas of joint action appears to be Türkiye’s main strategy. President Erdoğan’s active and intense leader-to-leader diplomacy has been a defining factor in the normalization process.27

While regional normalization has emerged as a new political inclination for most players, it continues to have certain limits. The first limitation is that normalization efforts have emerged against the backdrop of fierce competition on the global level. As the competition between the United States and China (and Russia and the West) evolves into violent confrontation day by day, systemic chaos might not have a positive impact on the region. That has been closely witnessed in the Russian intervention in Ukraine, as systemic competition morphed into a regional-conventional military conflict. In this context, another important point is that the United States has shifted its attention toward China, signaling that it has left the Middle East to fend for itself. Although the Biden Administration has made public statements contradicting that view, what happened in Afghanistan represents a lesson for the Middle Eastern players. With that said, Russian attempts to fill that power vacuum, together with China’s growing interest in the Middle East and Washington’s strategic ambiguity, could once again turn the region into a front of global competition.

The second important point is that many regional problems are yet to be resolved. The possibility of military or armed conflict in countries like Libya, Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq –not to mention Syria– has not ceased to exist. Another issue is the lack of a consensus vis-à-vis the political struggles that accompany those conflicts. For example, the postponement of the Libyan election, which was scheduled to take place on December 24, 2021, established yet again the difficulty of implementing decisions taken without political consensus. Meanwhile, the Syria talks continue slowly and remain far from an actual solution.

The third issue relates to the continued uncertainty surrounding Iran’s nuclear policy. It is obvious that Tehran needs to make concessions, rather than a single concession, for the Vienna talks to yield results. Yet each day that passes without a solution makes it more likely for Israel to facilitate an agreement between London, Washington, and the Gulf over a military solution against Iran. The risk of that possibility turning into a military conflict threatens to completely undermine the atmosphere of normalization in the region. Israel, which made significant progress vis-à-vis normalization with the Arab states under the Abraham Accords, would opt to prevent a rapprochement between the Gulf states and Iran. The regional players, which predict that Iran will become a nuclear power by 2030, are not expected to calmly accept that outcome. Furthermore, the likelihood of Tehran exploiting the room for maneuver that potential normalization with Washington would create for Iran to further its expansionist agenda makes regional governments nervous. As such, Iran possibly represents the weakest link in the regionwide normalization process. At the same time, Iran’s prominent role in Syria makes it likely for Tehran to undermine the normalization process between the Syrian regime and the Arabs –an important part of regional normalization. Again, Tehran shows no intention of leaving aside its sectarian ideological expansion, ballistic missile projects, or proxies, which it uses to exert influence over the region, as the Iranian leader Ali Khamanei’s statement –“political Islam is Iran”28– suggests. Quite the contrary, the country is far more likely to view the Gulf’s disunity and the possible reduction of U.S. pressure from an excessively confident perspective. That is why the Gulf states feel the need to work with countries like Türkiye and Israel against Iranian influence.

The fourth and possibly most important point relates to the idea of normalization itself. There is a lack of complete political consensus regarding any regional issue among the above-mentioned players. Neither the normalization process between Türkiye and Israel nor between Türkiye and Egypt are anywhere near the point where they would begin to generate a geopolitical consensus in the region. The same goes for the normalization processes between Israel and the Arabs, as well as among the Arabs.

Moreover, the continued existence of ideological divisions and conflicts of interest point to the risk that the four ongoing normalization processes might not lead to renewed regional stability and order.29 It is also possible that the regional players could use their repaired bilateral relations to form fresh blocs for regional competition. The pursuit of normalization in the Middle East, which involves a multitude of players and remains issue-based, must not be expected to create a lasting equilibrium in the near future. It goes without saying that there will be no absence of strong tensions in the region –even when diplomacy gains importance. Whereas the great powers, including the U.S., Russia, and China, shall continue to play an important role in the future of regional normalization, the decisions of regional powers will have more prominence. It is noteworthy that Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, countries that have close relations with the United States, have not joined Western sanctions against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine. It is also necessary to note that those nations that pursue normalization are inclined to act more independently.

Endnotes

1. For a study that engages in a multidimensional analysis of ideological, identity and power competition among the regional powers as a rivalry of different models (Saudi, Turkish, Iranian and Egyptian), see, Burhanettin Duran and Nuh Yılmaz, “Ortadoğu’da Modellerin Rekabeti: Arap Baharından Sonra Yeni Güç Dengeleri,” in Burhanettin Duran, Kemal İnat, and Ali Resul Usul (eds.), Türk Dış Politikası Yıllığı 2011, (Ankara: SETA, 2012).

2. The Qatar blockade of 2017 was the most striking example of the strategy of mutuel wearing down that eventually led to a direct attack. Had the blockade succeeded and power changed hands in Doha, that development would have had a notably different impact on the region. Regarding the Qatar blockade, see, Samuel Ramani, “The Qatar Blockade Is Over, but the Gulf Crisis Lives On,” Foreign Policy, (January 2021), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/01/27/qatar-blockade-gcc-divisions-turkey-libya-palestine/.

3. Richard Haaas, “The Post-American Middle East,” Project Syndicate, (December 2019), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/post-american-middle-east-by-richard-n-haass-2019-12.

4. Regarding the U.S. strategy of retrenchment, see, Joseph M. Parent and Paul K. MacDonald, “The Wisdom of Retrenchment: America Must Cut Back to Move Forward,” Foreign Affairs, (November/December 2011); Thomas Wright, “The Folly of Retrenchment: Why America Can’t Withdraw From the World,” Foreign Affairs, (March/April 2020); Charles A. Kupchan, “America’s Pullback Must Continue No Matter Who Is President,” Foreign Policy, (October 21, 2020).

5. Ufuk Ulutaş and Burhanettin Duran, “Ortadoğu’da Geleneksel Rekabet Mi, Bölgesel Dizayn Mı?” in Kemal İnat, Ali Aslan, Burhanettin Duran (eds.), Kuruluşundan Bugüne AK Parti: Dış Politika, (Ankara: SETA, 2018).

6. On Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and reactions to it, see Kadir Üstün and Kılıç B. Kanat, “Trump’s Jerusalem Move,” (Ankara: SETA, 2020).

7. Hussein Ibish, “Wary But Intrigued, Saudi Arabia Is Still Weighing Potential Ties to Israel,” The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, (September 2021), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://agsiw.org/wary-but-intrigued-saudi-arabia-is-still-weighing-potential-ties-to-israel/; Batu Coşkun, “Birinci Yıldönümünde İbrahim Anlaşmaları: Bölgeyi Nasıl Değiştirdi,” Sabah, (September 2021), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.sabah.com.tr/yazarlar/perspektif/batu-coskun/2021/09/18/birinci-yildonumunde-ibrahim-anlasmalari-bolgeyi-nasil-degistirdi.

8. See, Kemal İnat and Burhanettin Duran, “İran Yaptırımları: Hukuksal Boyut, Bölgesel ve Küresel Yansımalar Türkiye’ye Etkileri,” (Ankara: SETA, 2019).

9. Sayed Zafar Mahdi and Ali Abo Rezeg, “Regional Rivals Iran, Saudi Arabia Looking to Break Ice, Why Now?” Anadolu Agency, (October 2021), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/regional-rivals-iran-saudi-arabia-looking-to-break-ice-why-now/2396253.

10. Ghaida Ghantous and Aziz el Yaakoubi, “Stuck in the Middle? UAE Walks Tightrope between U.S, Israel and Iran,” Reuters, (December 2021), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.reuters.com/world/stuck-middle-uae-walks-tightrope-between-us-israel-iran-2021-12-12/.

11. “Türkiye’den Fanatik Yahudi Grupların Mescid-i Aksa Baskınına Tepki Mesajı,” Anadolu Agency, (May 29, 2022).

12. President Trump unveiled the Abraham Accords at the White House on September 15, 2020, alongside Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the Foreign Ministers of the UAE and Bahrain. Sudan and Morocco signed the agreement at a later date, increasing the number of Arab states that recognized Israel without an end to the occupation of Palestinian lands to four. Accordingly, those Arab states began to publicly cooperate with Israel on the security and economic fronts, even though that country had not abandoned its policy of building new settlements. The United States sold new weapons to the UAE, removed Sudan from its list of state sponsors of terrorism, and recognized Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara in an attempt to encourage normalization between Israel and the Arab states.

13. Zaha Hassan and Marwan Muasher, “Why the Abraham Accords Fall Short,” Foreign Affairs, (June 2022), retrieved June 9, 2022, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2022-06-07/why-abraham-accords-fall-short.

14. Abduljabbar Aburas and Halime Afra Aksoy, “Körfez Ülkeleri Ortak Dış Politika Belirleyebilir Mi?” Anadolu Agency, (January 2022), retrieved May 30, 2022, from https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/analiz/korfez-ulkeleri-ortak-dis-politika-belirleyebilir-mi/2466116.

15. Gerald M. Feierstein, Bilal Y. Saab, and Karen E. Young, “U.S.-Gulf Relations at the Crossroads: Time for a Recalibration,” Middle East Institute, (April 2022), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://mei.edu/publications/us-gulf-relations-crossroads-time-recalibration.

16. Jonathan Fenton-Harvey, “6 Months after al-Ula: Has the Gulf Crisis Really Ended?” Anadolu Agency, (July 2021), retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/analysis-6-months-after-al-ula-has-the-gulf-crisis-really-ended/2295423.

17. “Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr: Saudi Arabia Executes Top Shia Cleric,” BBC, (January 2016), retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-35213244.

18. “Houthi Attacks Expose Saudi Arabia’s Defense Weakness,” DW, (March 2022), retrieved May 30, 2022, from https://www.dw.com/en/houthi-attacks-expose-saudi-arabias-defense-weakness/a-61294825.

19. Maziar Motamedi, “Iran, Saudi Arabia Hold Fifth Round of Talks in Baghdad,” Al Jazeera, (April 2022), retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/23/iran-and-saudi-arabia-hold-stalled-5th-round-of-talks-in-baghdad.

20. Hamdan al-Shehri, “Russia’s Syria Withdrawal a Boon for Iran’s Regional Project,” Arab News, (June 2022), https://www.arabnews.com/node/2096641.

21. Some commentators, who labeled Erdoğan’s proactive foreign policy as Islamist or neo-Ottomanist, portray the policy of normalization as a concession or an admission of failure. Such claims have been refuted by the adaptation of Türkiye’s foreign policy approach to changing circumstances.

22. Burhanettin Duran, “BAE ile Nasıl Yeni bir Sayfa?” Sabah, (November 26, 2021); Amjad Ahmad and Defne Arslan, “Turkey and the UAE Are Getting Close Again. But Why Now?” Atlantic Council, (March 2022), retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/turkey-and-the-uae-are-getting-close-again-but-why-now/.

23. Çavuşoğlu’s visit related to reviving the joint economic committee, an agreement regarding civil aviation and the development of tourism. The parties postponed the discussion on the appointment of ambassadors, instead exchanging views on resolving the Israel-Palestine question, ensuring the safety of Eastern Mediterranean energy supplies, their delivery to Europe through a joint project, and the most recent developments in Syria. See, Haydar Oruç, “Türkiye-İsrail Normalleşmesinde Yeni Aşama: Çavuşoğlu’nun Ziyareti,” Anadolu Agency, (June 2, 2022).

24. Burhanettin Duran, “Normalleşme Süreci Testlerden Geçiyor,” Sabah, (April 22, 2022).

25. Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, “The Origins of Saudi-Turkey Rapprochement: Is It for Real?” Responsible Statecraft, (June 2022), retrieved June 8, 2022, from https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2022/06/07/the-origins-of-saudi-turkey-rapprochement/; Burhanettin Duran, “Suudi Arabistan’la Yeni Sayfa,” Sabah, April 30, 2022, https://www.sabah.com.tr/yazarlar/duran/2022/04/30/suudi-arabistanla-yeni-sayfa.

26. Ali Bakir and Eyüp Ersoy, “Saudi-Turkish Reconciliation Is a Cause for Concern in Iran,” Middle East Eye, (May 2022), retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/saudi-arabia-turkey-reconciliation-iran-concern.

27. Burhanettin Duran, “Synchronization Question in Turkey’s Normalization Policy,” Daily Sabah, (May 10, 2022).

28. Burhanettin Duran, “Kahire ile ‘Diplomatik Temas’ ve Yeni Stratejik Değerlendirm,” Sabah, (May 13, 2022), retrieved from https://www.sabah.com.tr/yazarlar/duran/2021/03/13/kahire-ile-diplomatik-temas-ve-yeni-stratejik-degerlendirme

29. For the argument that the U.S. withdrawal from the Middle East will revive sectarian rivalry rather than promote normalization, see, Vali Nasr, “All against All: The Sectarian Resurgence in the Post-American Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, (January 2022), retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2021-12-02/iran-middle-east-all-against-all.