For many years, political failures cast a shadow over the Turkish economy causing it to perform below its full potential. High levels of political uncertainty throughout the 1990s had a negative effect on a number of areas, including the economy. During this period, high inflation, accumulation of foreign debt, high budget deficit and high current account deficit left the economy vulnerable to domestic and international shocks. A series of coalition governments failed to take necessary precautions and to adopt appropriate policies. It was under these circumstances that Turkey experienced one of the most severe economic crises in its history in 2001. In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, the 2002 parliamentary elections caused several political parties to fail to secure representation in the national legislature and as such opened a new chapter in the country’s political history. The Justice and Development Party (the AK Party) won a landslide victory in the 2002 elections and embarked on a series of reforms in politics, the economy, foreign policy and other key areas that are collectively referred to as the New Turkey. The elections marked the end of a succession of coalition governments that crippled the country for eleven years.

Having risen to power in late 2002, the AK Party took steps to establish economic and political stability. During this period, the government introduced new regulations for the banking system, opted for fiscal discipline and privatized state enterprises. Government policies initiated a period of uninterrupted growth. Meanwhile, the AK Party took measures to strengthen public finance, increase public enterprises’ effectiveness and avoid the debt trap. Over the AK Party’s decade-long tenure, three successive governments comprehensively reformed the Turkish economy that currently outperforms a number of crisis-struck Eurozone countries in terms of various macroeconomic indicators.

For many years, political failures cast a shadow over the Turkish economy causing it to perform below its full potential

This study offers an analysis of Turkey’s economy over the past decade with reference to macroeconomic indicators, the transformation of public finances, novel social policies, improved relations with international organizations and changes in world economy following the global financial crisis in 2008. Finally, the study suggests measures to improve the economy’s current standing and elaborates on Turkey’s priorities vis-a-vis its 2023 targets.

Political Success and Economic Growth

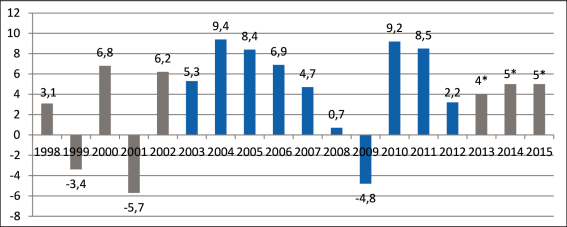

Global markets’ expansion and the availability of cheap credits following the 2001 financial crisis resulted in a significant increase in the flow of capital from financial markets to developing economies. During this period, wide availability of liquidity in world markets, combined with high real interest rates in Turkey, made the country an attractive destination.1 It was therefore that the economy recorded a 6.2 percent growth in 2002 to recover from a 5.7 percent contraction the previous year. Similarly, the country grew by 5.3 percent in 2003, 9.4 percent in 2004, 8.4 percent in 2005 and 6.9 percent in 2006. During this period, economic growth was not only due to an increasing volume of goods and services exported but also a revival of domestic demand. Meanwhile, a rising amount of foreign direct investments contributed to domestic production. It was due to all these reasons, as well as various precautions and post-crisis economic austerity program, that the Turkish economy gained resilience against external shocks and recorded one of the most rapid growth periods since 1950 between the years 2002 and 2007. (See Figure 1)

The 2008 global financial crisis affected the Turkish economy mainly through trade relations to some degree and resulted in a 4.8 percent stagnation in 2009. As a consequence of this stagnation period, Turkey embarked on a quest to reach out to new markets in the hopes of creating alternatives to the European Union, a trade bloc that comprises the vast majority of the country’s foreign trade volume. The establishment of trade connections with new markets, in addition to increasing domestic demand and export volumes, contributed to the Turkish economy’s recovery.

Figure 1. GDP Growth, Turkey (%)

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK)(2012), (*) Medium-Term Programme 2013-2015.

Turkey’s restructuring and revival of its real sector ensured that all sectors could contribute to economic growth and allowed the economy to perform extremely well in 2010 and 2011. During this period, the Turkish economy recorded an 8.5 percent annual growth to become the world’s second most rapidly growing economy –only second to China which grew by 9.2 percent in 2011. Moreover, the economy continued its growth pattern thanks to the government’s commitment to fiscal discipline and consistent economic policy at a time when Eurozone countries were severely effected by the global financial crisis. Although the Turkish economy recorded a humble 2.2 percent growth in 2012 and failed to meet expectations, this performance nonetheless showcased a variety of different economic activities in Turkey and demonstrated the relative dynamism of the country’s economic structures.

In the aftermath of the 2001 financial crisis and the subsequent period of recession, the Turkish economy consistently recorded high annual growth until the 2008 global financial crisis. Over the decade between 2002 and 2011, the economy grew by 6.5 percent on average –a strong performance compared to an average 4.7 percent over the past thirty years. According to OECD estimates, Turkey will record an annual 6.7 percent growth between 2011 and 2017 to become the most rapidly growing OECD country.2

The country’s strong performance in annual growth between 2002 and 2012 also exerted a positive effect on GDP per capita levels during the same period. In 2012, GDP per capita rose to $10,504 compared to $3,492 in 2002. Meanwhile, Turkey boosted its profile among developing countries with help from its economic growth. This development, however, made it an absolute necessity for the country to promote the production of high-added value products, to accumulate greater domestic savings to allow further growth and to concentrate its efforts on competitive business sectors in order to avoid the middle-income trap, a common problem for developing economies. Keeping in mind that the World Bank’s country classifications define countries whose GDP per capita remains below $1,105 as “low-income,” countries with GDP per capita between $3,976 and $12,275 as “middle-income” and countries with GDP per capita over $12,276 as “high income,” Turkey’s Middle-Term Plan for 2013-2015 aimed to increase GDP per capita to $12,859 by 2015 and thereby become a high-income country according to the World Bank’s criteria.

The Turkish economy gained resilience against external shocks and recorded one of the most rapid growth periods since 1950 between the years 2002 and 2007

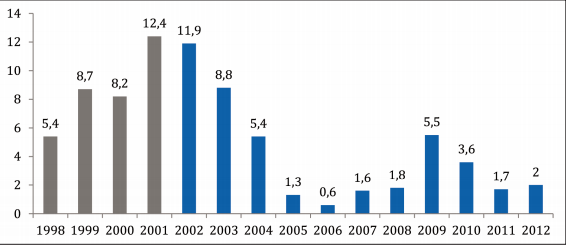

In addition to aforementioned improvements in economic growth, the AK Party government also took certain long-term measures to tackle high inflation, a traditional element of the Turkish economy. During the 1990s, a serious lack of economic stability caused short-term interest rates to skyrocket as the Turkish Lira’s weakening and excessive public spending during election seasons significantly added to high inflation. During this period, domestic savings diminished and domestic demand grew, leading the government to create funds through foreign debt. Moreover, the government made price and salary updates based on the inflation rates of previous years and therefore failed to tackle a structural obstacle before a much-needed decrease in inflation rates. The Turkish Lira’s rapid weakening over the course of the 1994 economic crisis similarly increased costs, while the government postponed public sector pricing arrangements only to witness double-digit inflation rates.3 High inflation resulted in the weakening of the Turkish Lira over the years and motivated successive governments to meet cash needs by printing high-value banknotes.4 Before long, this policy ironically turned every citizen into a millionaire. The AK Party’s economic reform programs and their repercussions pioneered efforts to transform macroeconomic structures that caused high inflation in the country for two decades.

The inflation targeting regime that the Turkish government adopted in the aftermath of the 2001 financial crisis determined and publicized inflation targets. Under this regime, the fundamental policy instrument available to the Central Bank was short-term interest rates. The Central Bank’s predictions regarding inflation and other economic indicators represented an early warning against inflationist pressures that may have arisen in the future and served as a guideline for Central Bank officials during decision-making processes regarding interest rates. The 2001 financial crisis resulted in Turkey’s moving away from “monetary policy based on currency rate targets” and adoption of “inflation targeting.” This approach allowed the Turkish economy to record single-digit inflation (9.4 percent) in 2004, following a stunning 54.4 percent in 2001. The economy’s rapid recovery, coupled with political determination, public support and economic stability, motivated the AK Party government’s 2005 decision to drop six zeros from the Turkish Lira.5

It was the 2008 global financial crisis that hindered Turkey’s maintenance of single-digit inflation. The inflation rate peaked at 10.1 percent in 2008 only to drop to single digits in 2009 and 2010. Following a 6.4 percent annual inflation in 2010, demand shocks related to unprocessed food, petroleum and gold –over which monetary policy has no control- triggered a 10.45 percent inflation in 2011. However, inflation rate dropped to 6.16 percent in 2012 –a historic low since 1968. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2. Inflation Rates, Turkey (%)

Source: Central Bank of Turkey; Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK).

The Development Offensive and Public Finances

Turkey’s institution of fiscal discipline in the aftermath of the 2002 parliamentary elections helped reduce the country’s budget deficit and subsequently improved the public’s fiscal balances. The AK Party government adopted a 2003 austerity program to lower inflation and reduce the budget deficit. Credibility, transparency and predictability represented consistent characteristics of the AK Party government’s annual budgets between 2002 and 2012. The government’s economic policy concentrated on a comprehensive privatization of state-owned enterprises and made efforts to reduce public spending. Between 2004 and 2007, the government continued to implement an economic program that concentrated on contraction measures for public finances. In the area of fiscal policy, the government simplified tax legislations, abolished a tax amnesty from the early 2000s and instead developed a ‘tax peace’ program that increased the number of taxpayers to expand its tax base. Additional tax revenues that these steps generated helped finance the government’s implementation of a new economic program. The Medium-Term Plan also reflected the government’s commitment to fiscal discipline vis-à-vis public finances. The plan estimated a decrease in government spending to GDP ratio of 1.8 percent in 2015.

Figure 3. Budget Deficit to GDP Ratio, Turkey (%)

Source: Ministry of Finance, Turkey.

Excessive foreign lending represented a serious challenge for the Turkish economy for an extended period of time. During the 1990s, Turkey’s accumulation of vast foreign debt resulted in inadequate foreign investment and consequently a significant slowdown in GDP growth. The country’s foreign debt, coupled with the government’s reliance on tax revenues from investment-based earnings to cover interest payments, led foreign investors to believe that Turkey would impose heavier taxes on their operations in the future and therefore refrained from investing in the country.6Unable to attract foreign investments, Turkey experienced greater difficulties in repaying its foreign debt and witnessed a significant drop in the influx of foreign currency. Meanwhile, real interest rates and foreign currency prices increased to worsen the situation and caused Turkey to accumulate heavy foreign debt that would take years to repay.7 In addition to Turkey’s risky outlook in global markets, international credit rating institutions’ recommendations added to the cost of borrowing for the country. A series of short-lived coalition governments, coupled with frequent elections, between 1990 and 2001 led to political and economic instability.

The AK Party successfully reduced the foreign debt to GDP ratio to ensure that the country would be able to repay and maintain its foreign debt. Government policies since 2002, coupled with a significant increase in Turkey’s annual GDP and therefore export volumes, helped improve debt indicators. During this period, Turkey even managed to outrank various European countries.8 While the country’s net foreign debt stock to GDP ratio amounted to 38.4 percent in 2002, the ratio decreased to 24.2 percent by 2012. Moreover, the public sector’s net foreign debt stock to GDP ratio decreased from 25.2 percent in 2002 to 0.6 percent in 2011. The ratio was lowered down to zero in 2012.

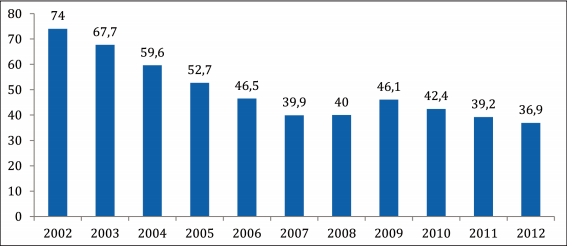

Furthermore, an analysis of Turkey’s EU-defined general management nominal debt stock would yield important information and allow for a comparison between Turkey and EU countries vis-à-vis the Maastricht Criteria, a pre-requisite for joining the EU’s economic and monetary union. While the Criteria stipulates that the debt stock ceiling cannot exceed 60 percent of any given country’s annual GDP, Turkey’s debt stock to GDP ratio has not surpassed the ceiling since 2004. Compared to an EU-defined general management debt stock to GDP ratio of 74 percent in 2002, Turkey performed rather well to reduce the ratio to 59.6 percent by 2004 and 36.9 percent by 2012 (See Figure 4). In this regard, all economic indicators would reveal that this significant decrease in debt-to-GDP ratio is due to the country’s consistent emphasis on fiscal discipline and its strong economic performance, as opposed to variations in definition.9 At a time when the global financial crisis hit European economies, the Turkish economy handled the situation successfully and became only minimally vulnerable to the repercussions of the crisis.

Figure 4. EU-Defined General Management Debt Stock to GDP Ratio, Turkey (%)

Source: Undersecretariat of the Treasury, Turkey.

Reformist Practices and Social Policy

The 1990s proved particularly challenging for Turkish governments that failed to include effective incentives to reduce unemployment and create jobs in their development programs. Meanwhile, successive governments relied on short-term remedies that they misbelieved would solve the problem of high unemployment, only to worsen the situation during periods of recession. Especially in the aftermath of the 2001 financial crisis, it became clear that Turkey’s high unemployment represented a chronic problem and that the country’s growth model failed to promote job creation. As such, Turkish government failed to reduce unemployment even though the economy steadily grew from 2001 onwards.10 Between 2002 and 2007, the unemployment rate remained around 10 percent. Long-term measures, however, began to create results in later years and, coupled with the country’s successful management of the global financial crisis, allowed Turkey to record an estimated 9.3 percent unemployment in 2013 and 8.7 percent in 2014 according to OECD experts –below Eurozone countries.11 The Medium-Term Plan estimated that unemployment would decrease 8.7 percent by 2015.12

Turkey’s post-2001 social aid regime developed a comprehensive network of social welfare programs and mandated a number of institutions and agencies for their implementation. During this period, the government provided additional funding for social aid programs in order to render low-income households less vulnerable to existing and future risks associated with economic crises. As such, the Social Risk Mitigation Project (SRMP) spent a total of $500 million between 2001 and 2006 to monitor and reduce poverty as well as to strengthen relevant institutions. Furthermore, the social aid regime covered medical costs of low-income citizens and offered in-kind and cash assistance through programs for children, students, the elderly and people with disabilities. Meanwhile, the government made additional funds available to government agencies that provide basic social services to low-income families. It was in this context that the Turkish government introduced the Conditional Cash Transfer Program, a social support system for the lowest income groups aiming to increase the efficiency of basic health and education services. Furthermore, government agencies took additional steps to allow low-income individuals greater access to social services for income generation and job creation.

In an effort to correctly identify rightful beneficiaries of social aid programs, the government introduced a “Scoring” system to ensure that social aid recipients’ entitlements would be independently assessed. The “Scoring” system took into account a multitude of social aid categories and inter-regional discrepancies with an eye on developing a more fair income distribution in the country by utilizing quantitative data to assess entitlements that would be confirmed by social workers through house visits. The new social aid system also facilitated information-sharing between various institutions to form a centralized database to correctly identify the applicants’ needs and to prevent beneficiaries from receiving simultaneous financial support through multiple public agencies. Similarly, the establishment of a new Ministry of Family and Social Policies in 2011 attested to the AK Party government’s commitment to enhancing the quality of social services. In this sense, the government allotted a greater share of the 2013 annual budget to the Ministry of Family and Social Policies than other ministries: The Ministry’s annual budget rose to TL 14.7 billion in 2013 compared to TL 8.8 billion the previous year. The Turkish economy’s strong performance also made additional funds available for social policies. While expenditures related to social aid and services amounted to 0.5 percent of Turkey’s annual GDP in 2002, total social spending including Social Security Agency’s various payments rose to 1.42 percent of GDP in 2011.13 In absolute terms, social spending increased from TL 1.376 million in 2002 to TL 18.216 million in 2011.

The establishment of trade connections with new markets, in addition to increasing domestic demand and export volumes, contributed to the Turkish economy’s recovery

Prior to the 2001 financial crisis, worsening inequalities in income distribution resulted in social and economic problems. As such, it had become apparent that greater fairness in income distribution constituted a priority item in Turkey’s agenda. The AK Party government adopted development programs and subsidy structures from 2002 onwards to reduce inter-regional discrepancies and ensure fairer income distribution in the country. Meanwhile, new regulations to promote competition, develop capital markets and lower inflation made significant contributions to bridging the income gap. Without question, underlying these improvements were various manifestations of the economy’s overall improvement such as consistent economic growth and GDP increase, lower risks and diminishing interest payments that generated new funding for social aid programs. Compared to 43.2 percent in 2002, the share of interest payments in the annual government budget dropped to 13.4 percent by 2012. Similarly, interest payments to GDP ratio fell from 14.8 percent in 2002 to 3.4 percent in 2012. It is therefore important to note that the vast majority of the government’s tax revenues before 2002 covered interest payments: while 85 percent of total tax revenues was spent on interest payments in 2002, only 17 percent of the government’s 2012 tax revenues was used to make interest payments to lenders. Similarly, Turkey’s consistent economic growth contributed to developments in income distribution.

The Changing Global Economy: Foreign Trade and Turkey’s Relations with International Organizations

Turkey’s strong growth performance and improved budgetary indicators boosted the country’s compatibility and integration with global markets to add to its competitiveness. While EU reforms revolutionized the economy and its financial markets, novel developments in the economy helped reduce the public sector’s liabilities and boost the financial sector’s efficiency. These improvements transformed Turkey into a regional player that attracted record levels of foreign investment. As such, Turkey experienced a vast influx of foreign direct investment (FDI) from 2002 onwards. Turkey’s post-2002 restructuring of the banking sector among others, coupled with fiscal reforms, rendered the country less vulnerable to external shocks and thereby strengthened its credibility. Having attracted a total of $19 billion in FDI between 1950 and 2002, Turkey received $22,047 million in 2007. Despite its relatively easy handling of the 2008 global financial crisis compared to its various competitors, Turkey experienced a sudden drop in FDI levels in 2008 only to recover the following year thanks to its strong financial infrastructure and increased resilience to shocks. Over the past nine years, Turkey received a total of $110 billion in FDI and ranked 13th among the world’s most attractive economies for FDI in 2012.14

Following the global financial crisis, inflation peaked at 10.1 percent in 2008, dropping to 6.16 percent in 2012 –a historic low since 1968

There is no question that a given country’s attractiveness to foreign investors heavily depends on its credit ratings from international financial services companies. From 2002 onwards, international financial service companies maintained their prejudice towards Turkey and therefore ignored a series of improvements to the country’s economy, such as high annual growth, shrinking foreign debt, political stability and a strong influx of foreign capital. In recent years, Turkey’s credit ratings failed to reflect its superiority to other indebted countries in terms of economic performance, debt indicators and stability and therefore created a sense of injustice.15 However, recent improvements in Turkey’s economy pressured international financial service companies to update the country’s credit rating. Therefore, leading institutions such as Fitch, Moody’s and JCR upgraded Turkey’s credit rating to investment grade (BBB-) over the past year. The 2012 upgrade marked the first time since 1994 that international financial institutions deemed Turkey an investment-friendly country. Improved credit ratings will no doubt have a positive influence on Turkey’s attractiveness to FDI.

Developments in global markets motivated Turkey to transform its foreign policy in harmony with its economic interests. The AK Party government’s efforts to build stronger ties with the Middle East and North Africa helped develop trade relations with these markets. Although the government’s foreign policy approach received criticism from pro-Western commentators, it nonetheless succeeded in diversifying Turkey’s trade partners. As such, bilateral free trade agreements and visa exemption treaties provided Turkish companies with a more diverse set of trade partners. Turkey’s development of stronger commercial ties with Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans in addition to Russia and China represented efforts to bring the country’s economy up-to-date with global economic developments since the early 1990s. The Turkish government adopted this global approach, a winning formula for developing economies, to complement its economic stability and active foreign policy.16

During the global financial crisis, Turkey succeeded in undoing the negative effects of the global financial crisis to seek alternative markets for its exports and turn the crisis’ challenges into new opportunities. While a number of EU countries failed to control their budget deficit due to monetary expansion policies and therefore lost their advantages in global commercial markets, the Turkish government’s commitment to fiscal discipline helped maintain its economic stability and boosted its credibility. Furthermore, Turkish companies diversified their trading partners in terms of both sector and country. In this sense, averting external demand shocks to record a steady export volume continues to represent a priority for the country. In order for Turkey to ensure further growth in its export volumes, it needs to render itself more competitive to survive in new markets. The Turkish economy thereby reduced the negative influence of the crisis to a minimum. To this end, the country reached out to new markets in the Far East, India, North Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. The Middle East and North African (MENA) countries in particular became the leading alternative consumer markets for Turkish products, as Turkey made efforts to strengthen its ties with MENA countries in a variety of sectors from 2010 on. Turkey’s exports to Asian markets (the Middle East, the Far East and others) comprised 39.1 percent of the country’s entire export volume in 2012 compared to a mere 28.3 percent the previous year.17 Although the increase in export volumes slowed down in 2009 following a strong uninterrupted performance since the 2001 economic crisis, the numbers recovered from 2010 onwards. In 2012, Turkey’s export volume reached a historic high at $151.8 billion compared to only $36 billion a decade ago.

On the other hand, over its 32 years of working with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Turkey was one of the most heavily indebted among 64 countries. During this period, the IMF provided a total of approximately $50 billion to Turkish governments. The economy’s rapid recovery since 2002, coupled with improved production and growth performance as well as public finances, allowed Turkey to repay the vast majority of its debt to the IMF. As such, the country paid off roughly $23.5 billion worth of foreign debt over an 11-year period to become debt-free in early 2013. Today, a number of developing countries including Turkey have committed to provide funds to the IMF in order to strengthen IMF resources and contribute to global financial stability. In this context, the Turkish government has made a commitment of $5 billion to the IMF’s international reserves.

Conclusion and Future Expectations

Turkey’s economy recorded a rather strong performance over the past 10 years and improved significantly vis-à-vis a number of indicators. There is little doubt that these improvements owed greatly to high levels of political and economic stability, Turkey’s demographic structure, the private sector’s capabilities and activities, as well as the country’s self-confidence in its region. In an attempt to highlight the centennial of the Republic’s establishment, the AK Party government announced that it aimed to increase the country’s GDP to $2 trillion and GDP per capita to $25,000 by 2023. Moreover, the government expects the annual export volume to reach $500 billion by 2023 and to double the total number of exporters to 100,000 companies. Without doubt, the most audacious among the government’s many objectives was for Turkey to become one of the 10 largest economies in the world by the Republic’s centennial. If the government is to meet its targets in exactly ten years, it must address certain structural problems ahead.

Keeping in mind that savings and investments fuel economic growth in Turkey and elsewhere, the country must develop a model whereby domestic savings engender necessary funds for investment. However, Turkey’s post-2002 economic growth and generation of income did not spill over to domestic savings. Unable to source necessary funds domestically, the private sector sought foreign capital –a leading cause of high current account deficit.18 Furthermore, Turkey’s lack of a healthy habit of savings, high reliance on foreign capital and lack of diversity for savings resulted in less than desirable amounts of domestic savings. Consequently, low levels of domestic savings in Turkey seriously jeopardize the country’s potential for sustainable growth. However, a rise in domestic savings would undoubtedly help increase the sustainability of Turkey’s current account deficit and thereby render the economy more resilient in the face of external shocks. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that domestic savings grow as public and private sector savings complement one another and the overall savings ratio remain steadily above 20 percent.

On the other hand, Turkey’s level of savings must be able to compete with other fast-growing countries with high levels of savings in order to meet the government’s 2023 targets. After all, there is an unmistakable positive correlation between countries’ savings, investments and economic growth. For instance, while China and South Korea maintain a surplus between savings and investments, Turkey currently records a negative difference between these two indicators. Keeping in mind that the level of savings reaches 52.6 percent in China and 29.3 percent in South Korea, Turkey must develop ways to boost savings in order to compete in the global marketplace.

The 2008 global financial crisis motivated countries across the globe to update financial designs, develop new regulation and monitoring approaches, and forge international alliances. The financial sector, with its ability to accumulate and distribute resources, integrate to global markets and capacity to offer high-added value products, emerged as the leading force behind economic growth.19

Turkey’s level of savings must be able to compete with other fast-growing countries with high levels of savings in order to meet the government’s 2023 targets

Meanwhile, among the government’s 2023 targets are the permanent lowering of inflation and interest rates to single digits and the emergence of Istanbul as one of the top 10 financial centers in the world. Moreover, sustainability represents a key factors in the financial sector’s performance. Therefore, Istanbul’s emergence as a leading financial center would lead Turkey’s efforts to ensure sustainability and growth. As such, the government’s plan for Istanbul bears strategic importance in a rapidly-changing global economy. Developing the necessary financial infrastructure and tax exemption policies would surely attract Middle East and Gulf capital over the medium-term.20 Keeping in mind that financial markets play a rather significant role in boosting savings, Istanbul’s new role as a financial market would no doubt make a positive contribution to the level of savings and serve as a leading force behind Turkey’s economic growth. In this respect, Istanbul’s emergence as a regional and global financial center would both attract international capital and add to domestic savings as well as prevent short-term international capital traffic from destabilizing the economy. Moreover, efforts to engender a hospitable environment for investors and address the need to inform the general public would help create a more transparent and reliable marketplace in Turkey, as additional investment and savings would create jobs and ensure economic growth.21

Another key issue for Turkey’s long-term objectives is to boost R&D spending. Keeping in mind that high-added value products prove crucial at times of economic crisis, R&D efforts would significantly improve the economy’s competitiveness in the global marketplace. R&D spending would also contribute to economic growth. However, universities must play a pivotal role in ensuring efficient cooperation between public and private sectors in covering R&D costs. The government must therefore provide additional funding for higher education and coordinate the simultaneous efforts of various institutions. Provided that the private sector’s R&D investments surpass public sector funding in developed economies, the Turkish government should promote cooperation between private and public sectors and encourage contributions from the industrial sector. For this purpose, the public sector must place greater emphasis on building an information economy to complement private sector investments. Furthermore, the country must add to its existing body of scientists in order to assist efforts to develop a knowledge-based economy. The government must take measures to ensure efficient employment for future university graduates and help prevent shortages of skill and information in order to establish a functioning labor market that corresponds to Turkey’s economic objectives. Such an approach would no doubt provide the country with the necessary tools to make a difference in the global marketplace and become more competitive.22

As the importance of energy policies come into prominence, Turkey must address its dependence on foreign energy and its long-standing current account deficit to meet Ankara’s long-term targets. After all, the country remains heavily dependent on energy as a key ingredient for domestic production –a leading cause of high current account deficit.23 As such, Turkey must concentrate its efforts on manufacturing products that are currently unavailable to produce domestically. Such efforts would no doubt reduce the need for imported goods and curb the country’s current account deficit.

Endnotes

- Nazan Susam, Ufuk Bakkal, “Kriz Süreci Makro Değişkenleri ve 2009 Bütçe Büyüklüklerini Nasıl Etkileyecek”, Maliye Dergisi, sayı 155, (Temmuz-Aralık, 2008).

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Economic Outlook (2010),”

from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic- outlook-interim-report- september-2010

_eco_outlook-v2010-sup1-en. - Türk Sanayicileri ve İşadamları Derneği (TÜSİAD), “1996 Yılına Girerken Dünya ve Türkiye Ekonomisi Raporu,” (Ocak, 1996).

- Mehmet Alagöz, “Paradan Sıfır Atmanın Gerekçeleri, Sonuçları ve Türk Lirasına İade-i İtibar,” Selçuk Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, (14), (2005), pp. 39-56,

- İbrahim Al, “Parasal Reformlar Kapsamında Türkiye’deki Paradan Sıfır Atılması Operasyonu Üzerine Bir Araştırma,” Karadeniz Teknik Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Trabzon, (Haziran, 2007).

- Paul Krugman, “Financing vs. Forgiving a Debt Overhang,” Journal of Development Economics, 29, (1988), pp.253-268.

- Ali Yavuz, “Başlangıcından Bugüne Türkiye’nin Borçlanma Serüveni Durum ve Beklentiler” SDÜ Fen Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 20, (Aralık, 2009), pp.203-226.

- Erdal Tanas Karagöl, “Geçmişten Günümüze Türkiye’de Dış Borçlar,” SETA Analiz, (Ağustos, 2010).

- Ibid.

- Dani Rodrik, “The Turkish Economy After The Crises,” Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA 02138, (November, 2009).

- OECD Economic Outlook, Vol. 2, (November, 2012).

- Kalkınma Bakanlığı, “2013-2015 Orta Vadeli Program, Temel Makroekonomik ve Mali Hedefler” (Ekim, 2012).

- T.C. Aile ve Sosyal Politikalar Bakanlığı Sosyal Yardımlar Genel Müdürlüğü, Sosyal Yardım İstatistikler Bülteni, (Eylül, 2012).

- Başbakanlık Yatırım Destek ve Tanıtım Ajansı, www.invest.gov.tr, http://www.invest.gov.tr/tr-

TR/turkey/factsandfigures/ Pages/Economy.aspx - Erdal Tanas Karagöl, “Geçmişten Günümüze Türkiye’de Dış Borçlar,” SETA Analiz, Ankara, (2010).

- Mehmet Babacan, “Whither Axis Shift: A Perspective from Turkey’s Foreign Trade,” SETA Policy Report, No. 4, (2010).

- Türkiye İhracatçılar Meclisi (TİM), “İhracat Rakamları,”(2012), http://www.tim.org.tr/tr/

ihracat-ihracat-rakamlari- tablolar.html. - T.C. Kalkınma Bakanlığı ve Dünya Bankası “Yüksek Büyümenin Sürdürülebilirliği: Yurtiçi Tasarrufların Rolü: Türkiye Ülke Ekonomik Raporu,” (2011).

- İstanbul Üniversitesi, Sermaye Piyasaları Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi (SERPAM), “İstanbul Bölgesi ve Uluslararası Finans Merkezi (İFM),” (Ekim, 2012).

- M. Emin Erçakar ve Erdal Tanas Karagöl, “Türkiye’ de Doğrudan Yabancı Yatırımlar,” SETA Analiz, (Şubat, 2011).

- Devlet Planlama Teşkilatı, “İstanbul Uluslararası Finans Merkezi Stratejisi ve Eylem Planı,” Ankara, (2009).

- Dilşad Erkek, “Ar-Ge, İnovasyon ve Türkiye: Neredeyiz?,” T.C. Güney Ege Kalkınma Ajansı, (2011).

- Rüstem Yanar, Güldem Kerimoğlu, “Türkiye’de Enerji, Tüketimi, Ekonomik Büyüme ve Cari Açık İlişkisi”, Ekonomi Bilimler Dergisi, Cilt,3, No:2, (2011).