Introduction

In the wake of the dissolution of the former Soviet Union, the Caucasus and Central Asia have emerged as some of the world’s most unstable regions. The countries in the region have not been particularly successful in building strong, developed political and economic systems, nor in establishing stable national sovereignty. In addition, the countries face major security risks.

In the South Caucasus, the Russo-Georgian war in 2008, and the ongoing Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, both reflect the lack of security in the region. Domestic ethnic conflicts, transnational crime, and political and economic instability also characterize the region.1 In the midst of this instability, the South Caucasus has become a major arena of competition between international powers such as the United States, the EU and Russia, as well as adjacent countries including Turkey and Iran. The heightened importance of the South Caucasus for Turkey was initiated by several factors. Turkey’s initial bid for permanent membership in the EU, initiated in the late 1980s, marked the beginning of a slow negotiation process between Turkey and the European Council which, after thirty years, has still not culminated in EU membership. Turkey’s policy makers, frustrated by the endless stalling of this process, eventually redirected the country’s foreign policy to rethink the country’s strategic position in world politics. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s marked major fallout for Turkey, namely the loss of its role as a regional buffer for the West against the Soviet threat.2 These two factors could have led to the marginalization of Turkey among its Western allies. However, there were some factors that made Turkey an interesting partner for its Western partners both in the South Caucasus and Middle East regions. First, then President Özal’s pro-Western stance and legacy, combined with Turkey’s support of the US-led operation during the First Gulf War, in which Turkey played a profound pro-Western role, squarely positioned Turkey as a loyal strategic partner for the West.3 Further, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the newly emerging independent states in the Caucasus and Central Asia provided another source of opportunity for Turkey to increase its strategic ties with the West. Moreover, in the early 1990s, many in the West viewed Turkey’s pro-Western and secular political system as an ideal model for the newly emerging Caucasian and Central Asian countries, in contrast to Communism, and the type of Islamism initiated by Iran.4 Well aware of this perception, Turkey attempted to take advantage of these opportunities and carve out a central role for itself in the region.

From Russia’s standpoint, Turkish presence in the region is equivalent to Western influence, and hence a decrease in its own power

In addition to its importance in the political context, the South Caucasus is rich in oil and gas, which is paramount for its economic ties with Turkey. For instance, Azerbaijan has frequently been Turkey’s strongest Caucasian economic partner especially since mid-2000s. The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline (active since 2006), and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) natural gas pipeline (active since 2007) are cornerstones of Turkey-Azerbaijan economic relations. Already in 2008, Turkey was Azerbaijan’s second largest trade partner, with 18.2 percent of its imports coming from Turkey.5 The same held for 2010, with overall trade volume amounting to $2.416 bn; by 2013, trade volume had reached $3.3 bn.6 Turkey is presently the first country for Azerbaijan’s imports and eleventh for its exports; the trade volume between the two countries surpassed $5 bn.7 Ali Babacan, Turkish Deputy Prime Minister, stated that “We now aim for $15 billion in trade by 2023”.8 Georgia has also been a key partner for Turkey in the South Caucasus. In 2008, Turkey was Georgia’s largest trading partner both in imports ($15.1bn) and exports ($19.3bn).9 Turkey presently ranks first as Georgia’s largest trading partner for imports and sixth in its exports.10 These statistics could be of the indicators of the importance of the South Caucasus for Turkey’s economy and foreign policy.

In spite of the pivotal role of the South Caucasus for Turkish economics, Turkey has not been able to successfully follow up on its policies and establish its influence to the full extent desired. In the 1990s, Turkey’s domestic economic crisis and political unrest presented significant obstacles that limited Turkey’s regional influence.11 Russia’s persisting hegemony and its attempts to maintain the status quo are additional factors thwarting Turkey’s endeavors in the region. From Russia’s standpoint, Turkish presence in the region is equivalent to Western influence, and hence a decrease in its own power.12 Turkey has also been cautions in its relations with Georgia due to its strong economic ties with Russia. Another important impediment to Turkey’s overall role in the region stems from its economic relationship with Azerbaijan, which has been at war with Armenia since the 1980s. To date, Turkey has no diplomatic relations with Armenia, and its borders remain closed. Ostensibly, this is due to Armenia’s claim regarding “the Armenian Genocide” of 1915 in Ottoman Turkey and Western Armenia, a claim that Turkey has, to date, refuted.13

Since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923, the foreign policy of the country has been guided by two main principles. The first one is the “construction and maintenance of peace in its neighboring region and the world,” and the second, “Kemalism with its program for modernization along Western, secular lines”.14 However, Turkey’s early foreign policy stance towards the Central Asian and Caucasian states was mainly based on the Turkic-oriented idea of “A Turkish World from the Adriatic Sea to the Chinese Wall”, a stance that determied its political and economic policies within this geographic frame. However, this initially myopic conception of neighbours that ignored non-Turkic states has undergone a deep transformation since the early 2000s, giving way to “interdependency, economic cooperation, regional integration, proactive foreign policy, as well as peace and stability”. Further, Turkey has more recently based its relations with its region on the principle of “Zero Problems with Neighbors”.15Turkey’s foreign policy towards its neighbors has thus shifted to four main principles: a) the establishment of the mechanisms of high-level political dialogue, b) economic interdependence, c) the development of regional policies that could include all regional actors, and d) coexistence in peace, diversity, and tolerance of differences.16

Some contend that with the rise of the AK Party, Turkey’s foreign policy has deviated from the West. They argue that Turkey has turned more towards the East and the Islamic world. However, the real transformation of Turkey’s foreign policy has less to do with East-West than the concepts of “Strategic Depth” and “Rhythmic Diplomacy” developed by Ahmet Davutoğlu. These foreign policy tenets call for active and effective engagement with all regional systems in Turkey’s neighborhood, including the South Caucasus. “Davutoğlu advocates that Turkey should act as a central state regionally and that it has the potential to become a global actor in the future”.17 As one of the main architects of Turkey’s modern foreign policy, Davutoğlu believes that Turkey is a pivotal country with multiple regional identities. Thus, it does not fit into a narrow, singular category. “In terms of its sphere of influence, Turkey is a Middle Eastern, Balkan, Caucasian, Central Asian, Caspian, Mediterranean, Gulf, and Black Sea country all at the same time”, a country that should appropriate a position in the region that provides security and stability not only for itself, but also for its neighbours and the larger region.18 Davutoğlu’s conception provides Turkey with a leadership role, rather than a position as a simple bridge connecting the East to the West. On the basis of this conception, Turkey has been conducting a twofold foreign policy: a) relying on multilateralism and taking a more active role in international relations, and b) extending its relations with counries in the region where previously it has had little contact.19

Turkey is considered a latecomer to the Caucasus region due to its unsuccessful policies prior to the early 2000s. However, more recently, on the basis of Davutoğlu’s principles, Turkey has been able to take a more active approach in the region.20 The role played by Turkey in the South Caucasus (as well as the Middle East) is highly valued by both the United States and many European countries. Turkey’s role in these regions, based on its current foreign policy, has gained support of the US and the EU. They point out that Turkey has been able to do in regions such as the Caucasus what the EU would wish to do but has been unable to.21 In addition, Turkey has had an impact on Russia’s regional policies. Russia has exhibited concerns over Turkey’s presence in the South Caucasus; its actions reflect its policy of keeping Turkish influence at bay, on the supposition that Turkish influence could be followed by more Western influence, which would threaten Russia’s present hegemony in the region.

However, despite Turkey’s active role in the South Caucasus, and its attempts to expand its influence, it has not been able to fully achieve its desired results due to many factors. Regarding its multidimensional role in the region, Turkey has faced many challenges in shaping its relations with its Caucasian neighbors. Significantly, Turkey’s strong economic interdependence with Azerbaijan has highly affected its normalization process with Armenia, resulting in a profound strategic dilemma. The 2008 Russo-Georgian War put pressure on Turkey regarding its policy and approach towards Georgia, which became the main battlefield between Russia and the West, with Russia attempting to strengthen its leverage, while Western powers worked to prevent ambitious Russia from increasing its dominance over the region.

Turkey’s Stance on Normalization of Relations with Armenia

Although Turkey was the first country after the United States to recognize Armenia’s independence after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, relations between these two neighboring countries have not yet been normalized. To date, no bilateral diplomatic relations have been established, and the borders are sealed. Turkey made an effort to start the normalization process immediately following Armenia’s independence. Also, Turkey supported Armenia’s admittance to the regional organization of the Organization for the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC), headquartered in Istanbul. However, in spite of both of these overtures as well as the attempts of the first president of Armenia, Levon Ter-Petrosyan (1991-1998) to normalize relations, Turkey’s foreign ministry was reluctant to establish diplomatic relations with Armenia.22 This reluctance was exacerbated by the eruption of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in 1993, when Turkey interceded in the advance of Armenian troops in Azerbaijan.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict initiated a darker round in Turkish- Armenian relations. The war made Turkey so suspicious of Armenia that Armenian flights crossing Turkish airspace were inspected to stop arms smuggling. Another event that worsened Turkish-Armenian relations was the election of Robert Kocharian in 1998. Kocharian had vocally advocated for international recognition of the 1915 Armenian Genocide; Turkey’s response was to suspend air links between the two countries and impose more Turkish visa restrictions upon Armenian citizens during 2000 and 2001.23 In general, in spite of the alleged inclination on the part of both countries toward normalization, a great deal of mistrust grew between the two during the 1990s, which effectively stalled the normalization process.

With some justification, Turkish-Armenian normalization was perceived as a great threat in Azerbaijan

The rise of the Justice and Development party (AK Party) in Turkey initiated a new round of attempts at normalization. Turkey’s new foreign policy, based on the “Zero Problems with neighbors” principle encouraged Turkey to take a more active stance for normalization. Turkey additionally felt the necessity of normalizing relations with Armenia to achieve its regional purpose, namely the “preservation of peace, security, and stability in the triangle formed by the Balkans, the Middle East, and the Caucasus.24 In order to achieve this, in a broader scope, Turkey has attempted to promote economic interdependence in these regions. In addition, in regard to the South Caucasus, it worked to champion the idea of the “Caucasus Solidarity and Cooperation Platform (CSCP)” after the Russo-Georgian war, and has conducted numerous high-level diplomatic contacts to promote it.25 Turkey is aware that a definitive move towards normalization on its part would hold positive implications for its relations with the European Union. These ambitions have prompted Turkey to take a more dynamic approach towards the normalization process in recent years.

Both countries have actively shown interest in normalizing relations. Among the most noteworthy efforts made by Turkish President Abdullah Gül and Prime-Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was that they were the first foreign leaders to congratulate President Sargsyan on his election in February 2013.26 Also, what came to be known as “football diplomacy” gave a positive veneer to their relations. Presidents Sargsyan and Gül respectively invited each other to visit the World-cup qualifying football matches between the two countries.27 There were other events that could be qualified as a rapprochement: six meetings between the top officials of both countries between 2003 and 2008, Turkey’s tolerance of about 70,000 illegal Armenians in Turkey, and the preservation of Armenian historical and cultural sites within Turkish borders. However, a number of setbacks rendered the process unsuccessful. Two main factors hindered the process: Armenia’s persistence that Turkey recognizes the 1915 Genocide, and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Having given a sketch of Turkey’s policy towards the normalization process, in this section, the influence of each of these two factors on Turkey’s stance will be discussed next.

Armenia’s Persistence that Turkey Recognize the 1915 Genocide

Armenia has long tried to use the 1915 genocide issue as leverage to exert more political pressure on Turkey and use it as a kind of leverage. The Armenian lobby calling for international recognition of the 1915 Genocide has been successful to a large extent. They have been able to gain ground on the issue both in the United States and in the European Union (recognition in Europe dates back to 1987; recognition in the US remains undecided).28 The US government and the EU have used this issue as a tool to pressure Ankara on such issues as EU accession and the status of Iraq’s Kurdish populated Northern provinces.29 In response, Turkey has attempted to keep the issue of genocide out of the international agenda. In 2005, Erdoğan wrote an official letter to Kocharian proposing a formal fact-finding mission, composed of both Turkish and Armenian experts and historians, to form a commission. However this letter was rebuffed by Kocharian, who reiterated the need to normalize relations and deal with the political realities of the present as a necessary context for any meaningful inquiry into the events of 1915.30 In addition, according to Osman Bengur, an American politician of Turkish descent to run for Congress in the United States and a commentator on this issue, Turkey has often tried to counteract Armenian attempts to gain recognition on the Genocide issue. He stated, “By some accounts, approximately 70 percent of the Turkish Embassy’s time in Washington is spent trying to persuade leading Americans to support the Turkish position on the Armenian question”.31

Turkish society seems to have taken a different and softer approach to the Genocide issue, compared to the Turkish government’s official position. Take, for example, the internet signature campaign, called the “I am sorry campaign”, which was launched by 200 Turkish intellectuals to express their sorrow and apology for what happened in 1915 in Ottoman Turkey. This movement was harshly criticized by Prime Minister Erdoğan.32 However, some scholars believe that Turkey’s official stance regarding the issue has changed during the last couple of years. They contend that Turkey has implicitly recognized the genocide. They consider Turkey’s request for an “expert mission and investigation” as evidence of this change in policy.33 Further, they submit that the international recognition of the issue by such world powers as the EU, and their use of the issue as a means of political leverage on Turkey, has caused Turkey to reduce its resistance against it. In the long run, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan may pose a more important obstacle for normalization.

The Nagorno-Karabagh Conflict

Although such issues as the Armenian traditional stance on Kars and the 1915 Genocide have been touted as the main hindrances to the normalization process, neither of these have been as impactful as the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This issue is the main factor that has kept the normalization process frozen since the two countries signed the Zurich protocols in October 2009.

As noted above, Azerbaijan has been Turkey’s closest regional partner with a high volume of trade between two countries. In addition, Azerbaijan is one of the main energy suppliers for Turkey, with two active pipelines including the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) natural gas pipeline. As such, Azerbaijan stands to play a key role in Turkey’s ambition of becoming a key regional energy hub for Europe. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia has thus deeply influenced Turkey’s stance on normalization with Armenia.

Since 1993, when the conflict started, Turkey has actively brought the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh to the normalization debates.34 Until 2008, Turkey’s main and explicit position was that Armenia should withdraw its troops from Karabakh if the country is really willing to get the borders unsealed and diplomatic relations started. For its part, Armenia has tried to keep the issue of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict off the table and disconnect it from the normalization process.35 The turning point in Turkey’s stance towards the Nagorno-Karabakh issue in the context of normalization changed during the build-up to the Zurich Protocols. During this time, informal contacts such as “football diplomacy” and hidden talks between the officials had reached a new dimension of formalization. It seemed that in the protocols that were ultimately signed, Armenian withdrawal from Nagorno-Karabakh was not proposed as a precondition. On 22 April 2009, the foreign ministers of Turkey, Switzerland, and Armenia jointly released a statement saying that “the two parties have achieved tangible progress and mutual understanding in this process and have agreed on a comprehensive framework for the normalization of their bilateral relations in a mutually satisfactory manner. In this context, a road-map has been identified”.36 It immediately became clear that Turkey had not insisted upon the precondition of Armenian withdrawal. Nor did the US, which supported the protocols, make any causal links between normalization and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The agreement on the protocols and President Obama’s speech in Turkey supporting the normalization process sparked strong reactions from Azerbaijan against normalization. With some justification, Turkish-Armenian normalization was perceived as a great threat in Azerbaijan. Baku’s concern rested on the argument that the normalization of relations and the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict must follow parallel paths. Normalization without any link to the conflict would deter its resolution37 and US support of the process without any respect to the conflict increased this concern.

Baku’s increased attention to Russia posed a risk to Turkey’s goal of becoming a regional energy hub, and threatened to weaken Turkey’s energy- and non-energy-related economic ties with its strongest Caucasian partner

The reactions of Baku to the signing of the protocols initiated a crisis in Turkish-Azerbaijani relations. Immediately after the protocols were signed, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev publicly condemned the rapprochement and called it a mistake.38 He also cancelled his scheduled participation in the Alliance of Civilizations conference (April 6-7) that was to be held in Istanbul. In response to Turkey’s impulse toward normalization, Azerbaijan followed three broad strategies, all of which attempted to avoid direct confrontation with the Turkish government. First, Baku tried to “mobilize the public opinion through media on the negative implications of an unconditional Turkish-Armenian rapprochement on Turkish-Azerbaijani relations”. Second, they tried to establish links with the two Turkish opposition parties, the Nationalist Movement party (MHP) and the Republican People’s Party (CHP), both of which opposed the rapprochement because of its negative influences on relations with Azerbaijan. Third, Azerbaijan announced in various official meetings and conferences that it “might consider shifting the direction of its energy cooperation toward Russia”. Making good on this assertion, in 2010 the State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SOCAR) decided to sell 500 million cubic meters of gas a year to Russian Gazprom at a price of US $350 per thousand cubic meters.39

Turkey’s response to Baku’s reactions can be divided into two main phases. During the first phase, Turkish officials attempted to convince Baku that the agreement would hasten the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. They intimated to Azerbaijani officials that the Nagorno-Karabakh issue was included in the agenda of rapprochement. President Gül, for instance, announced that “Turkey thinks of Azerbaijan in her every act”.40 However, Baku remained dubious for several reasons including the fact that a) the positions of the Armenian officials did not confirm Turkey’s claims, b) the Nagorno-Karabakh issue was not included in the actual text of the protocols, and c) Turkey’s hidden negotiations with Armenia had made Azerbaijan very suspicious of the issue.41

At the start of the five day Russo-Georgian conflict, Turkey faced a heavy burden and found itself in the midst of a significant strategic dilemma

Azerbaijan’s firm stance convinced Turkey that the greater the rapprochement with Armenia, the greater the distance from Azerbaijan. Baku’s increased attention to Russia posed a risk to Turkey’s goal of becoming a regional energy hub, and threatened to weaken Turkey’s energy- and non-energy-related economic ties with its strongest Caucasian partner. Azerbaijan’s gambit of shifting its attention to Russia in regard to energy issues concerned Turkey greatly. In a cost-benefit analysis, it was more beneficial for Turkey to suspend the normalization process. In May 2009, Erdoğan, in a visit to Azerbaijan, declared that “[t]here is a relation of cause and effect here. The occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh is the cause, and the closure of the border is the effect. Without the occupation ending, the gates will not be opened”.42 The normalization process has been in suspension since then. If not the only factor, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was certainly one of the most influential hindrances of the rapprochement.

The Russo-Georgian Conflict

As one of the first countries to recognize the independence of Georgia after the dissolution of the USSR, Turkey has developed strong relations with Georgia. Georgia holds strategic significance for Turkey for several reasons. As a smaller and weaker neighbor, Georgia is considered a buffer zone for Turkey against gigantic Russia. Second, due to the deadlock in relations with Armenia, Georgia is the only country through which Turkey can reach Azerbaijani oil and gas. Bypassing Russia and Iran, Georgia is the best option for the transportation of Caspian energy to international markets through Turkey.43 Georgia acts as a crossroads for the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline, the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum natural gas pipeline, and the Kars-Tbilisi-Baku railway projects. In exchange for this extreme strategic importance, Turkey has supported Georgia in its economic, political, and military development. For example, Turkey aided the Georgian army in conforming to NATO standards by providing military training in some areas and by modernizing its institutions.44 Turkey helped Georgia modernize the Batumi Airport, and continued to work on this process even during the five day Russo-Georgian war.

In spite of Georgia’s strategic role, which in some ways buffers Turkey from Russia, Russia is of vital importance for Turkey too. Russia has long been a major trading partner, and Turkey’s energy dependence on Russia plays a major role in the big picture of economic relations between the two countries. Turkey depends on Russia for 29 percent of its oil and 63 percent of its gas. The amount of natural gas imported to Turkey from Russia had reached 27.33 bcm in 2014, from 10.08 million Cm3 in 2001.45 By 2014, the trade volume between Turkey and Russia reached $33 billion, and in December 2014, the two states agreed to increase their trade volume to $100 billon by the end of 2020.46 In short, Russia’s dominance in the Caucasus region, and its position as a main source of energy for Turkey’s consumption, which affects its energy hub ambitions, makes Russia a big player in the region vis-à-vis Turkey’s interests. Moreover, Russia’s importance has always made Turkey cautious in its relations with Georgia, so that Russia would not be disturbed.47

At the start of the five day Russo-Georgian conflict, Turkey faced a heavy burden and found itself in the midst of a significant strategic dilemma. On the one hand, Turkey was torn between the two states: Georgia, with which it had strong strategic ties, and Russia, on which it was economically dependent. From the perspective of the West, Turkey, as a NATO member and close ally of the US and the EU, was expected to support Georgia against Russia’s imperialistic and assertive act. Realistically, this was a far-fetched expectation due to Turkey’s dependence on Russia.

When the conflict started, Turkey did support for Georgia. This support was not military, however, but humanitarian. 100,000 tons of food aid was sent to the war-hit country, and 100 houses were built for refugees in Gori.48 In spite of the humanitarian impulse behind Turkey’s actions, Russia accused Turkey, along with some other countries, of supporting Georgian militants, and labeled them accomplices of what Russian officials called the “genocide” that the Georgian military had perpetrated against the South Ossetians.49 Russia also accused Turkey of letting American and European naval ships into Georgia through the Turkish straits. Some scholars believe that the inspection of Turkish trucks by Russians in mid-August was a retaliation for this act on the part of Turkey.50 However, others contend that it was the result of the deadlocked customs regulations negotiations between Turkey and Russia that dated back to early 2008 and just happened to coincide with the Russian-Georgian war.51

Turkey, with its position as a US and EU ally and NATO member on the one hand, and its multidimensional partnership with Russia on the other, was pressured both by the West and by Russia. As the dominant power in the region, Russia was set on increasing its leverage against the West. The US and the EU on the other hand, have always been set on increasing their influence in the South Caucasus. In order for this to happen, US strategy has assumed that Turkey’s alliances with Azerbaijan and Georgia would create a strategic transit corridor and turn Turkey into a major energy conduit for Europe.52 They feared that Russia’s attack on Georgia would lead to Moscow’s control of the vital strategic corridor of the South Caucasus, and “Russia would reassert its influence over the energy supply routes and suppliers from Caspian Sea basin”.53 Such an outcome would in no way be favored by the US and the EU, nor by Turkey with its strong ambitions to becoming a key energy hub. Torn in this power contest between the West and Russia, not only did Turkey have to serve its own interests, but it was also expected to serve the interests of its Western allies as well.

It could be contended that Turkey’s initially active policy towards the normalization of relations with Armenia was associated with the Russo-Georgian conflict

Turkey has always tried to avoid taking sides in any “Russia versus the West” struggles, and, since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, has attempted to develop its own relations with Moscow. The same policy was adopted in the Russo-Georgian conflict. Turkey’s stance towards the issue was existential. Rather than taking the US or Russian side, Turkey attempted to take an independent position and follow its own national interests. Erdoğan clarified this policy by saying, “It would not be right for Turkey to be pushed toward any side. Certain circles want to push Turkey into a corner either with the United States or Russia after the Georgian incident. One of the sides is our closest ally, the United States. The other side is Russia with which we have an important trade volume. We would act in the line with what Turkey’s national interests require”.54 Ahmet Davutoğlu likewise described Turkey’s policy towards the conflict as neutral. He claimed that although Turkey belongs to the Western block, it should not be expected that Russo-Turkish relations be like Norwegian or Canadian-Russian relations. In a meeting with members of the Council on Foreign Policy (CFR) organization and other American journalists in Ankara, Davutoğlu stated, “Any other European country can follow certain isolationist policies against Russia. Can Turkey do this? I ask you to understand the geographical conditions of Turkey. If you isolate Russia, economically, can Turkey afford this? … Unfortunately, we have to admit this fact. Turkey is almost 75-80 percent dependent on Russia [for energy]. We don’t want to see a Russian-American or Russian-NATO confrontation… We don’t want to pay the bill of strategic mistakes or miscalculation by Russia, or by Georgia”.55

Before the conflict, Turkey played an ambivalent role in the region. Its main objectives were to back political and economic pluralism in the region, and at the same time, maintain multidimensional ties with Russia. Regional pluralism would mean the political and economic sovereignty of the South Caucasian states and a reduction in Russian influence. On this basis, Turkey has always attempted to help these countries individually in promoting their stability and prosperity in ways that could, in turn, promote regional peace and stability.56 This approach has two benefits for Turkey. First, it allows Turkey to pursue its strategic aim of becoming a regional energy hub with open hands. The BTC and BTE pipelines are evident examples. At the same time, supporting peace and stability increases Turkey’s power and central role in the region, hence increasing Western influence as well. However, the five-day Russo-Georgian conflict changed the rules. The conflict, and Russia’s success, meant that it could easily take control of the two BTC and BTE pipelines; the security of these pipelines was clearly at risk57 and the feasibility of the Nabucco pipeline was called into question.58

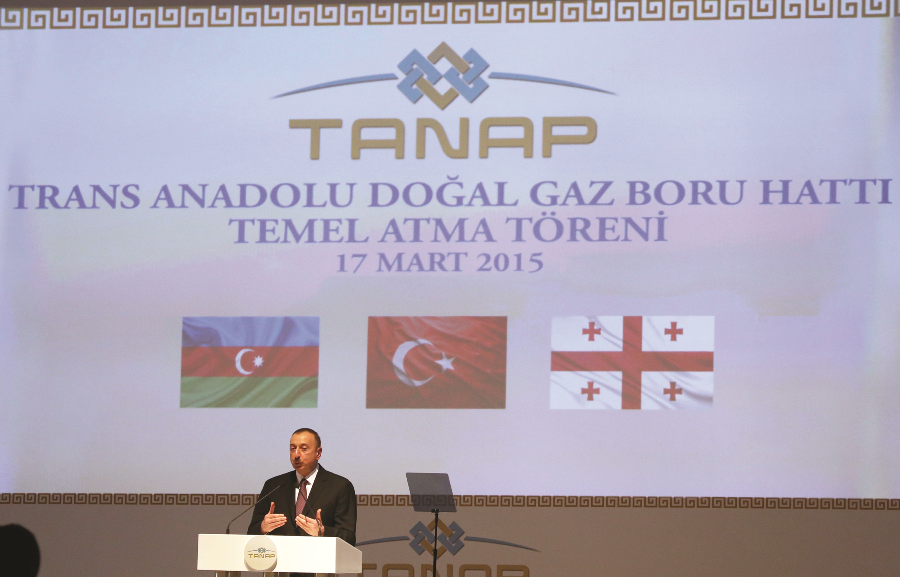

President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, giving a speech during the opening ceremony of TANAP (The Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline). | PHOTO AA / AHMET OKATALI

President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, giving a speech during the opening ceremony of TANAP (The Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline). | PHOTO AA / AHMET OKATALI

As a result of the consequences of the war, particularly Russia’s increased dominance in the region, and given the fact of Turkey’s energy and economic dependence on Russia, Turkey has since attempted to strengthen its ties with Russia in regard to South Caucasus issues. The Russo-Georgian conflict conveyed to Turkey that Russia is willing to be strongly assertive in the interest of retaining its dominance in the South Caucasus; thus, cooperation with Moscow is the only way for Turkey to increase its influence and pursue its interests in the region.59 Following this line of reasoning, Turkey proposed the “Caucasian Stability and Cooperation Platform” that included Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. The aim of the platform was to promote peace and stability in the region through diplomacy and debate. Also, the platform would increase Turkey’s chances of becoming an energy hub, since one of the main aims of Turkey is to stabilize the energy transit routes in the region.60 Abdullah Gül expressed this very explicitly: “The Caucasus is a key as far as energy resources and the safe transportation of energy from the East to the West. That transportation goes through Turkey. That is why we are very active in trying to achieve an atmosphere of dialogue, so there is the right climate to resolve the problems. If there is instability in the Caucasus, it would be sort of like a wall between the East and West; if you have stability in the region, it could be a gate”.61

It could be contended that Turkey’s initially active policy towards the normalization of relations with Armenia was associated with the Russo-Georgian conflict. Given the threat posed by the conflict to the existing pipelines passing to Turkey through Georgia, and skepticism about the success of future pipeline projects in connection with Georgia such as Nabucco, a rational step for Turkey would be to seek for other routes of energy transit, and Armenia as an immediate neighbor could be the best option.

Energy Issues with Azerbaijan

Although the nature of Turkey’s positive relations with Azerbaijan has been thought to be the two countries’ shared cultural, lingual, and ethnic heritage, the main factor shaping their strong strategic bilateral relationship in the 21st century is the energy factor. Turkey’s ambition to diversify its energy imports, and to become a central energy hub in the region, and Azerbaijan’s possession of rich energy resources among the South Caucasian countries, have made Azerbaijan a strategic South Caucasian player for Turkey. Accessing Azerbaijan’s energy resources also decreases Turkey’s energy dependence on its two rival neighbors, Iran and Russia. Seeking integration into the global economy, Baku has attempted to gain a foothold in the American and European energy markets. Its main aim has been to play a significant international role by leveraging its energy resources.62 The country has also aimed to increase its leverage against Armenia and decrease its dependence on Russia by developing its resources. To achieve these aims, Baku has attempted to build strong ties with the West through Turkey.63 In addition, by making Turkey dependent on its energy, Baku could also prevent Turkey from normalizing relations with Armenia if doing so were to go against its interests regarding the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Four energy contracts have been signed between Turkey and Azerbaijan. These include the Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhun (BTC) and the Baku-Tblisi-Erzurum (BTE) that are now operational; the proposed but stalled Nabucco; and the Trans Anatolia Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) agreement that was signed in late October 2011. The BTC agreement, signed in 1994 and operational by 2006, was the main pipeline transferring Azeri oil to Turkey and Europe. This was a US-sponsored energy corridor project aimed at Western energy diversification, and was called the contract of the century.64 The BTE pipeline, also known as South Caucasus pipeline, that has been operational since 2007 transfers natural gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz I gas field to Turkey through Georgia. Turkey is to enjoy 6.6 billion cubic meters of natural gas through this pipeline.

The Nabbuco gas pipeline was similarly sponsored by the EU, and was aimed to transfer gas from the second Azerbaijani gas field, Shah Deniz II, to Europe through Turkey. From Turkey, the pipeline would stretch to Austria, via Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, and was expected to transport some 30 bn cubic meters per year by 2020 from the Caspian, the Middle East and Egypt, improving the EU’s energy security.65 However, the project did not succeed. Azerbaijan’s main aim in establishing Nabucco was to create a pipeline that could make European markets directly accessible.66 However, the project hit a deadlock. Russian countermoves (e.g. introducing the South Stream Project), declining energy consumption as a result of the global economic crisis, and difficulty in resolving financing issues are some of the most important factors thwarting the project.67

Diversification of energy resources is as important to Turkey as it is to the EU

The most recent and most important project is the Trans Anatolia Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) that is intended to become a main gas corridor to Turkey and the European markets. What distinguishes it from BTE and Nabucco is its capacity to carry gas from Shah Denis II as well as other suppliers in the future. “TANAP, an 1841 km-long pipeline, will carry 16 bcm of Azerbaijani gas to Europe via Georgia and Turkey, entering Turkey from the Georgian border and exiting from Thrace. Once it has crossed the Turkish border to Europe the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), an 870 km-long pipeline, will carry the Azerbaijani gas to Italy”.68

The TANAP project has started a new deeper round of energy negotiations between Turkey and Azerbaijan and will advantage Turkey in several ways in comparison to the previous projects. As a result of two agreements forged between Baku and Ankara in HLSC meetings, Baku will both transfer and sell gas to Turkey, enabling the country to re-export the bought gas.69 Turkey will also own a 30 percent share of the project. By owning the project, the country can move beyond a mere transit role and become an influential and strategic partner to the project. Through TANAP, a huge amount of natural gas, priced lower than what Turkey currently pays on average, is bestowed upon Turkey, a win that will increase its leverage against Iran and Russia. The pipeline will also increase Turkey’s chances of becoming a major energy hub.70 Regarding Russia as the big power in the South Caucasus, some consider TANAP a nightmare for Russia on the ground that it is a project like PTC or Nabucco from a Russian point of view.71 Others contend that TANAP does not pit Turkey (or Azerbaijan) against Russia as much as Nabucco would have, because although Nabucco aimed to provide gas to the same markets as the Russian South Stream pipeline, TANAP’s focus will be on Southern Europe. Moreover, a “10 billion bcm supply to Europe is not a challenge to Russia considering European gas demand and Russian supply capacity”.72 In short, the TANAP project stands to advantage Turky in its potential to become a regional hub.

Turkey’s main goal in the South Caucasus region has focused on friendly and stable relations with all regional countries

Diversification of energy resources is as important to Turkey as it is to the EU. The diversification of energy markets is similarly important for energy producer countries such as Azerbaijan. Turkey has tried to play a central role for both sides in its diversification policies.73 On 27 March 2007, addressing the AK Party parliamentary group meeting, Erdoğan said that “the EU is in search of solutions to serious security, energy, enlargement, ageing population and labor force issues”, and added: “Turkey is the answer to the energy issues”.74 The country has been able to win a high level of international support for its four pipeline contracts with Azerbaijan. The BTC and BTE pipelines were US and EU supported projects that have helped shape the backbone of the East-West energy corridor. Thus by pursuing positive relations and energy ties with Azerbaijan, Turkey has been able to play a central role regionally that is also beneficial for the EU in terms of energy transit. This factor could be considered a positive point in terms of its EU accession. And, at the same time, Turkey could to satisfy its soaring energy needs.

Turkey’s pipeline policies in the region are multidimensional. Although Turkey has followed its pipeline strategies primarily in pursuit of its vision of becoming a regional energy hub, it should be noted that its pipeline policies have also contributed to Turkey’s goal of establishing peace and stability in the South Caucasus. With the BTC, BTE and TANAP pipeline projects, Turkey has contributed to the development of peace, stability, and prosperity through its strategy of creating peace through economic interdependence.

Conclusion

With the advent of the Justice and Development Party (AK Party), Turkey’s foreign policy has been based on the concept of “Strategic Depth”. The concept has given Turkish foreign policy a multidimensional approach and a multifaceted identity to the country itself. Turkey has attempted to base all its policies towards its neighbors in the region on the “Zero Problems with Neighbors” principle, and to take an active role in establishing peace, stability, and prosperity in its neighboring domain. As such, Turkey’s foreign policy has given it a central role in the region.

Turkey’s main goal in the South Caucasus region has focused on friendly and stable relations with all regional countries, supporting regional pluralism, and helping the individual countries develop their economic and political independence, peace, stability, and prosperity. The success of this policy could guarantee Turkey’s increased power in the region, hence more leverage against Russia and Iran, and increase its chances of becoming a regional energy hub. More important, this goal is aligned with Turkey’s strategic vision of having zero problems with neighbors. Thus, achieving it would mean a partial achievement in having no problems with neighbors. Building friendly and stable relations with the South Caucasus countries can enhance Turkey’s position for its Western partners such as the EU and the US since by building such relations, Turkey can increase Western influence in the region, hence giving the EU and the US more leverage against Russia. However, the country has faced some serious obstacles.

Normalization of relations with Armenia hit deadlock on two accounts. The most important challenge that faced the normalization process with deadlock was the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The normalization seems to remain in suspension pending the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The prospects of resolution are poor, given Azerbaijan’s stubbornness and Russia’s reluctance to help resolve the issue as the dominant regional power. Armenia’s occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh has isolated the country from the international community and made it highly dependent on Iran and Russia. Russia’s understanding of the normalization is an increase in Turkish and Western power in the region and a decrease in Armenia’s dependence on Russia; that Russia would never want to happen, and its ambitions of increasing its dominance in the region and remaining a hegemon renders the success of normalizations increasingly unlikely.

The five day Russo-Georgian conflict changed the geopolitical conceptions of the region. The security of two major pipelines, the BTC and the BTE, was called into question, given Georgia’s instability and Russia’s easier access to the pipelines as a result of the conflict. Although Turkey adopted a more cooperative approach to increasing peace and stability in the region after the conflict, it still lacks sufficient leverage to secure either its current pipelines or its future projects due to its economic and energy dependence on Russia. Turkey’s attempts to normalize relations with Armenia have been interpreted by some analysts as attempts to find more secure routes for its pipelines. Turkey’s neutral policy during the Russo-Georgian conflict and its cooperative approach after the conflict may be politically warranted, but this approach does little to expand Turkey’s ambitions in the region. The conflict of interests between Russia and Turkey, and Turkey’s reduced leverage after the war decrease the viability of Turkey’s vision of becoming energy hub. However, Turkey’s recent moves in regard to the TANAP+TAP appear to bypass the specter of Russian conflict and have increased the prospects of Turkey’s success in its energy ambitions.

Taking a deeper perspective, it could be claimed that (at least) one of the bases of Turkey’s challenges in the South Caucasus lies in the conflict of interests between Russia and West. Turkey’s interests have long been interwoven with those of the West. Yet the economic dependence of the regional countries on Russia and their economic and political vulnerability keep them from making independent decisions. Russia, as the main hegemon, does not and will never welcome increased Turkish influence, which it views as increased Western influence. Therefore, Turkey will face significant challenges in achieving in its ambitions in the region.

Some critics may disagree with this paper’s emphasis on Turkey’s “Zero Problems with Neighbors” policy due to this policy’s apparent failure during the normalization process and in the context of the recently emerging conflicts between Turkey and its immediate neighbors such as Syria and Iran after the Arab Spring. However, it should be noted that this paper does not aim to justify Turkey’s policy or confirm its appropriateness. Instead, the main aim was to explain Turkey’s behavior in the South Caucasus on the basis of this policy and to delineate the domestic and international challenges that the country faced in following this policy in the South Caucasus. We argue that, in accordance with its policy, Turkey has attempted to have the best possible relations with its South Caucasus neighbors; however, Turkey has not been completely successful in this regard due to domestic and international pressures.

Turkey’s problems with Syria, Iraq, and Iran after the Arab Spring do not fall within the scope of this paper. However, it should be noted that Turkey’s “zero problems with neighbors” policy should not be considered a complete failure. The tensions that were created between Turkey and its immediate neighbors including Iran, Syria, and Iraq after the Arab Spring have diminished on the basis of the recent trends in the Middle East and Turkey’s practical steps in reducing these tensions. Turkey’s resignation to the reality of transition in Syria under Assad has and will play a significant role in the improvement of its relations with Iran. Turkey has attempted to depict itself as a nonsectarian state in the Middle East. Allowing an influx of Syrian refugees into its territories and sending humanitarian aid to Iraq after the ISIS attacks indicate that Turkey may be attempting to follow a different type of foreign policy, one referred to as the “2.0 version of the zero problems with neighbors policy”.75 Hence, it would be more sensible to regard this policy as a process with ups and downs, rather than a fiasco.

Endnotes

- Younkyoo Kimand Gu-Ho Eom, “The Geopolitics of Caspian Oil: Rivalries of the US, Russia, and Turkey in the South Caucasus,” Global Economic Review, Vol. 37, No. 1 (2008), p. 85-106.

- Ertan Efegil, “Turkish Ak Party’s Central Asia and Caucasus Policies: Critiques and Suggestions,” Caucasian Review of International Affairs, Vol. 2, No. 3 (2008), p. 166-172.

- Ibid.

- Muhittin Ataman, “Özal Leadership and Restructuring of Turkish Ethnic Policy in the 1980s,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4 (2002), p. 123–142.

- Michael Bishku, “The Foreign Policy Concerns of the South Caucasus Republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia,” Middle East Institute New Dehli, Occasional Paper (May 2010).

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK), retrieved July 4, 2015 from http://www.tuik.gov.tr.

- State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan, retrieved June 16, 2015 from http://www.stat.gov.az.

- “Azeri Oil Firm to Invest $10 Billion in Turkey’s Petkim,” Hürriyet Daily News (May 13, 2015), retrieved July 4, 2015 from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.

com/azeri-oil firm-to-invest-10-billion-in- turkeys petkim.aspx?pageID=238&nID= 82352&NewsCatID=348. - Bishku, “The Foreign Policy Concerns of the South Caucasus Republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia”

- National Statistics Office of Georgia (GeoStat), retrieved July 3, 2015 from http://www.geostat.ge/index.

php?action=0&lang=eng. - Bülent Aras and Pınar Akpınar, “The Relations between Turkey and the Caucasus,” Perceptions, Vol. 16, No. 3 (2011), p. 53-68.

- Aybars Görgülü and Onnik Krikorian, “Turkey’s South Caucasus Agenda: The Role of State and Non-State Actors,” Eurasia Partnership Foundation (TESEV Foreign Policy Program), (2012).

- Aras and Akpınar, “The Relations between Turkey and the Caucasus,” p. 53-68.

- Laura Batalla Adam, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy in the AKP Era: Has There Been a Shift in the Axis?,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 3 (2013), p. 139-148.

- Aras and Akpınar, “The Relations between Turkey and the Caucasus,” p. 53-68.

- Ibid.

- Adam, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy in the AKP Era: Has There Been a Shift in the Axis?,” p. 139-148.

- Ahmet Davutoğlu, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2007,” Insight Turkey ,Vol. 10,

No. 1 (2008), p. 77-96. - Adam, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy in the AKP Era: Has there been a Shift in the Axis?,” p. 139-148.

- Görgülü and Krikorian, “Turkey’s South Caucasus Agenda: The Role of State and Non-State Actors”

- Emiliano Alessandri, “The New Turkish Foreign Policy and the Future of Turkey-EU Relations,” Istituto Affari Internazionali, (2010).

- Ricardo Torres, “The Normalization Process between Turkey and Armenia,” Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales, (2011).

- Ibid.

- Ismail Cem, “Turkish Foreign Policy: Opening New Horizons for Turkey at the Beginning of the New Millenium,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, (2002).

- Ziya Oniş and Şuhnaz Yılmaz, “Between Europeanization and Euro-Asianism: Foreign Policy Activism in Turkey during the AKP Era,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (2009), p. 7-24.

- Aybars Görügü, Sabiha Senyücel Gündoğar, Alexander Iskandaryan and Sergey Minasyan, “Turkey-Armenia Diologue Series: Breaking the Vicious Circle,” Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation, (2009).

- Bülent Aras and Hakan Fidan, “Turkey and Eurasia: Frontiers of New Geographic Imagination,” New Perspectives on Turkey, No. 40 (2009), p. 195-217.

- Sergey Minasyan, “Prospects for Normalization between Armenia and Turkey: A View from Yerevan,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2010), p. 21-30.

- Osman Bengur, “Turkey’s Image and the Armenian Question,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 1 (2009), p. 45.

- Ricardo Torres, “The Normalization Process between Turkey and Armenia,” Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales, (2011).

- Ibid.

- Aybars Görgülü and Onnik Krikorian, “Turkey’s South Caucasus Agenda: The Role of State and Non-State Actors”

- Ibid.

- Ricardo Torres, “The Normalization Process between Turkey and Armenia,” Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales, (2011).

- “Joint Statement of The Ministries of Foreign Affairs of The Republic of Turkey, The Republic of Armenia and The Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs,” Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (2009).

- Zaur Shiriyev and Celia Davies, “The Turkey-Armenia-Azerbaijan Triangle: The Unexpected Outcomes of the Zurich Protocols,” Perceptions, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2013), p. 185-206.

- “Azerbaijan Seeks to Thwart Turkish-Armenian Rapprochement,” retrieved July 3, 2015 from http://www.rferl.org/content/

Azerbaijan_Seeks_To_Thwart_ TurkishArmenian_Rapprochement/ 1603256.html - Zaur Shiriyev and Celia Davies, “The Turkey-Armenia-Azerbaijan Triangle: The Unexpected Outcomes of the Zurich Protocols,” p. 185-206.

- “Abdullah Gül’den Önemli Açıklamalar,” Yeni Şafak, April 29, 2009.

- “Turkish-Armenian Secret Talks Wiretapped,” Musavat, (April 17, 2009), retrieved January 20, 2012 from http://www.musavat.com/new/G%

C3%BCnd%C9%99m/51432-T%C3% 9CRK%C4%B0Y%C6%8F ERM%C6%8FN%C4%B0STAN_G%C4% B0ZL%C4%B0_DANI%C5%9EIQLARI_D% C4%B0NL%C6%8FN %C4%B0L%C4%B0B. - “Erdoğan Puts Baku’s Armenia Concerns to Rest,” Today’s Zaman, May 14, 2009.

- Hasan Ali Karasar, “Saakashvili Pulled the Trigger: Turkey between Russia and Georgia,” SETA Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, (2008).

- Ibid.

- Muberra Pirinçci, “Turkish Russian Relations in the Post-Soviet Era: Limits of Economic Interdependence,” thesis submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, (2009).

- “Russian Gas Delivery Statistics,” Gazprom Global Energy Company, retrieved July 3, 2015 from

http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/statistics/. - Bihter Bozbay and Eylül Topanoğlu, “Turkey: Commercial Relations Between Turkey And The Russian

Federation,” Mondaq, (June 20, 2014), retrieved July 3, 2015, from http://www.mondaq.com/turkey/x/

321956/international+trade+investment/Commercial+ Relatons+Between+Turkey+And+ The+

Russian+Federation. - “2008’de Türkiye-Gürcistan İlişkileri,” Hürriyet, December 19, 2009.

- Igor Torbakov, “The Georgia Crisis and Russia-Turkey Relations,” The Jamestown Foundation, (2008).

- Sinan Ogan, “Rusya Gümrük Krizinin Gerçek Sebebi ve Alınacak Önlemler,” Turkish Forum, (2008).

- Aras and Fidan, “Turkey and Eurasia: Frontiers of New Geographic Imagination,” p. 195-217.

- Torbakov, “The Georgia Crisis and Russia-Turkey Relations,” The Jamestown Foundation, (2008).

- “Russia’s Grip on Energy,” Financial Times, August 26, 2008.

- Torbakov, “The Georgia Crisis and Russia-Turkey Relations”.

- Ahmet Davutoğlu, “Turkey’s Top Foreign Policy Aide Worries about False Optimism in Iraq,” Council on Foreign Relations, (September 19, 2008), retrieved September 19, 2008 from http://www.cfr.org/turkey/

turkeys-top-foreign-policy- aide-worries-false-optimism- iraq/p17291. - Ibid.

- Elizabeth Douglass, “Russia-Georgia Conflict Raises Worries Over Oil and Gas Pipelines,” Los Angeles Times, (2008).

- Jad Mouawad, “Conflict in Georgia Narrows Oil Options for West,” International Herald Tribune, (2008).

- Vitaly Dymarskii, “Kavkazskii igrovoi krug,” Rossiiskaia Gazeta, (2008).

- Eleni Fotiuo, “Caucasus Stability and Cooperation Platform: What is at Stake for Regional Cooperation?,” International Centre for Black Sea Studies, (2009).

- Rana Foroohar, “Pulled From Two Directions,” Newsweek, (2008).

- Massimo Gaudiano, “Can Energy Security Cooperation Help Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan to Strengthen Western Oriented Links?,” Academic Research Branch, Research Note, No. 5, (2007).

- Şaban Kardaş, “The Turkey-Azerbaijan Energy Partnership in the Context of the Southern Corridor,” Institutio Affari Internazionali, (2014), p. 1-12.

- Fariz Ismailzade, “Turkey-Azerbaijan: The Honeymoon is Over,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, (2005), retrieved from http://www.turkishpolicy.com/

images/stories/2005-04- neighbors/TPQ2005-4- ismailzade.pdf. - Gaudiano, “Can Energy Security Cooperation Help Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan to Strengthen Western Oriented Links?”

- Bülent Aras, “Turkish Azerbaijani Energy Relations,” Istanbul Policy Center, Policy Brief 15, (April 2014).

- Katinka Barysch, “Should the Nabucco Pipeline Project be Shelved,” CER Policy Briefs, (2010).

- Aras, “Turkish Azerbaijani Energy Relations,” (April 2014).

- Emin Emrah Danış, “Shah Deniz Keeps Contributing to the Development of Turkey and the Region,” Hazar World, No. 16 (March 2014), p. 38-48.

- Kardaş, “The Turkey-Azerbaijan Energy Partnership in the Context of the Southern Corridor,” p. 1-12.

- Sevim Tuğçe Varol, “Importance of TANAP in Competition Between Russia and Central Asia,” International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, Vol. 3, No. 4 (2013), p. 352-359.

- Efgan Niftiyev and Fatih Macit, “Energy Future of Europe and the Role of the Southern Corridor,” Caspian Strategy Institute, Center on Energy and Economy, (2013), retrieved from https://w w w .academia.edu/4920038/Energy _Future_of_Europe_and_the_

role_of_The_Southern_Corridor. - “Erdoğan Tells EU to Make Up Its Mind about Turkey,” Zaman, (March 28, 2007), retrieved from

http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/detaylar.do?load=detay& link=106723&bolum=103. - Haydar Efe, “Turkey’s Role as an Energy Corridor And Its Impact on Stability in the South Caucasus,” OAKA, Vol. 6, No. 12 (2011), p. 118-147.

- Gaudiano, “Can Energy Security Cooperation Help Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan to Strengthen Western Oriented Links”

- Tarık Oğuzlu, “The ‘Arab Spring’ and the Rise of the 2.0 Version of Turkey’s ‘Zero Problems with Neighbors Policy,” Center for Strategic Research, No. 1, (February 2012), p. 1-16.