Energy resources are the most important commodities in the world economy today. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), it will take at least $5.4 trillion over the next two decades to ensure the security and adequacy of petroleum for world consumption.1 This increasing cost in oil exploration puts high-energy consuming countries in a vulnerable position. It also poses an intricate challenge for other countries that are dependent on oil, especially for industrialization. Two of the consequences of these trends are that energy security is now an important domestic and foreign policy matter and that states look for alternative energy sources more vigorously than ever before. American, European, Russian, and Chinese foreign policy makers, as well as those from other developing nations, are increasingly trying to establishing links with resource rich areas to secure sources of petroleum.

A New and Important Energy Frontier

Because of the significant oil and gas deposits of the Caspian basin, the Central Asian republics have attracted increased global attention.2 As documented by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), this attention was triggered by the fact that the Caspian holds significant oil and gas deposits, fueling hopes of great untapped reserves that might rival even those of the Persian Gulf. The optimistic estimates about the region’s potential have meant increased interest in its political and economic affairs by multinational corporations (MNCs), the European Union, China, and the United States. The newfound geopolitical influence, says the UNEP, is seen by the major export pipeline routes being built throughout the region. This section provides a synopsis of the region’s potential.

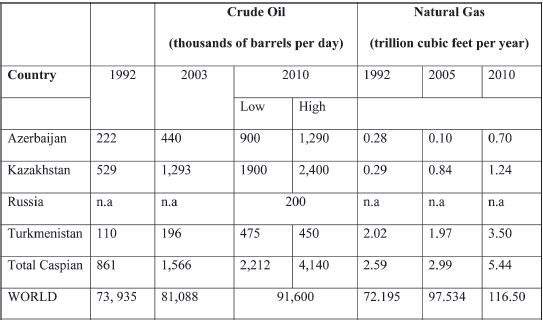

Table 1. Oil and Gas Production in the Caspian Sea Region

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), the Caspian Sea shelf is potentially one of the largest sources of hydrocarbons outside the Persian Gulf and Russia.3 Some 700 miles long, the Caspian Sea has historically been a place for oil and natural gas production.4 The EIA expects much greater production of these resources than at present (Table 1).5 In a time when such resources are becoming scarce, the region represents one of the world’s new great frontiers for exploration opportunities. Currently, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are the region’s largest producers. While the estimates for Caspian oil and natural gas resources vary, analysts agree that it is of a substantial size to affect the world’s energy supply. Estimates of oil reserves range widely from 85 to 200 billion barrels (bbls) of crude oil. Of those, the region’s oil production has absolute capacity to economically recover 17-18 bbls.6 The US Department of Energy (DoE) estimates that Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan alone combine for 110 billion barrels.7 Kazakhstan currently produces 1.6% of the world’s total oil output and this is set to increase to 3.5% by 2030.8

With its growing economy and energy needs, it is indeed in Turkey’s interest to see the Caucasus region stable with strong sovereign states

The region’s abundant stock of natural gas contributes far more to world energy supply than the oil reserves.9 Estimates for the total gas output in 2003 were about 2.6 trillion cubic feet per year (tcf/yr).10 This accounts for 3% of world production. The region has yet to reach the productive capacity offered by its reserves and current production of natural gas continues to be lower than the actual reserves estimates would indicate. The region’s proven reserves of natural gas stand between 170 tcf and 262 tcf, with Turkmenistan accounting for nearly two thirds. As evident in these numbers, Central Asia is inevitably crucial in the competitive push to secure energy supplies.

The Heartland Theory and the Current Competition for Control

The developments in the past decade have shown that states must realign their national energy security policies from a purely military affairs angle to prioritizing stable oil markets. Whereas the imbalance between output (supply) and consumption (demand) cannot be balanced any time soon, one way to prevent volatile oil prices would be to have stability in regions that are well endowed with oil and natural gas resources. With its growing economy and energy needs, it is indeed in Turkey’s interest to see the Caucasus region stable with strong sovereign states. This requires direct and effective engagement with the states of the region and development of broad-based relations in multiple fields. However, numerous economic and political problems emerge as individual states, particularly the United States, Russia and China, claim and defend various geostrategic interests. Turkey’s strained relations with Armenia and the somewhat-lukewarm relations with Azerbaijan, mainly due to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, also create handicaps for effective Turkish foreign policy in the region. Formulating a Turkish strategy to deal effectively with the opportunities and challenges in the region is no easy task but this paper will discuss a number of policy options later.

Turkey’s strained relations with Armenia and the somewhat-lukewarm relations with Azerbaijan, mainly due to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, also create handicaps for effective Turkish foreign policy in the region

The Caspian Sea—the world’s largest body of inland water—houses much of the oil deposits of the region. It is located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, Russia and Iran, and links Central Asia to the Caucasus and Turkey.11 The independence of the region from the Soviet Union opened its resources to international markets, driving speculation about the promise of untapped markets previously consolidated under Soviet rule. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the republics surrounding the Caspian Sea on the eastern shore declared independence to form five separate countries in the heart of the Eurasian continent: Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. On its western shore lies an almost equally important former Soviet region, the Caucasian states of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia, a prospective member of NATO. The Caspian region stretches for about 4,500 kilometers and makes up the largest area in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), an organization formed after the disintegration of the Soviet Union.12 The region has an abundant supply of mineral resources that includes petroleum, natural gas, and rare metals.13 For nearly a century, the region was a protectorate of Russia, which controlled all forms of commerce and designated it as an internal market base for Soviet market expansion. The Russian-Caspian postcolonial relationship persists today. Russia has continued efforts to assimilate the region into its political sphere of influence. Three of the Central Asian republics (CAR), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, are members of the Eurasian Economic Community (EAEC), an organization led by Russia.14 Kazakhstan has already joined Russia in signing the 2003 Common Economic Space (CES) agreement. Both the EAEC and CES are subsets of the CIS. The CIS’s overall goal is to facilitate the deepening of an integrated community in economic matters. In general, Russia has in effect implemented, or is attempting to form, a geo-economic union akin to the early formation of the EU.

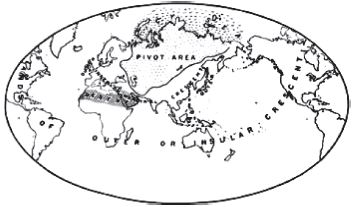

With Russia to the north, Afghanistan and Pakistan to the southeast, Iran to the west and the Xinjiang province of China to the east, Central Asia is one of the most pivotal geographical areas of the world.15 It sits strategically between the Caucasus and links the peripheral landmasses of Russia with Europe and the Middle East. According to the “Heartland Theory” of H.J. Mackinder, who discussed the role of “pivotal regions” in his 1904 The Geographic Pivot of History, (1) who rules Eastern Europe commands the Heartland; (2) who rules the Heartland commands the World-island; and (3) who rules the World-island commands the World (see Figure 1).16

Figure 1. “Pivot Area” and Mackinder’s “Heartland Theory”

The Heartland partially comprises the Central Asian and Caucasian states, practically placing them as the main bridge to the Caspian, the Heartland itself. Therefore, access to Central Asia’s resources spans national, regional and world-wide influence. The Caucasus, in this context, is a strategic door. Though not well articulated in the theory itself, the two regions simultaneously reinforce each other when seeking influence in the Caspian. Generally put, the theory posits that the Central Asian countries are the core of the Heartland and they feature prominently in assessing the degree to which it is conclusive that there indeed exists a power competition in the region. The effective control of the Caspian’s resources then transcends the particular Central Asian countries. Full control gives internal and regional influence that extends to surrounding states like Georgia and Azerbaijan—the Caucasus.

Since the demise of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, there has been a revitalized interest in the natural resources, mainly oil and natural gas, in the Caspian region. Though not yet united in a common energy policy, the EU seeks to cement its trade relations with the region as it receives about 30% of oil and 40% of its gas imports from Russia. The United States has taken a more aggressive role in relations with the Caspian countries. Immediately following the dissolution of the Soviet bloc two decades ago, the first Bush Administration noted in its 1990 National Security Strategy that the US indeed had interest in preventing any power or group of powers from dominating the Eurasian landmass.17

Current geostrategic struggles parallel the “Great Game,” the 19th century imperial rivalry between Czarist Russia and the British Empire over Central Asia. Contemporary actors that replaced these two powers are post-Soviet Russia, China, and the United States.18 Although Iran, Turkey, and Pakistan are also important players in the arena, the US presence is arguably substituting for the British as the new contender for influence in the post-Soviet power vacuum. In formulating their energy policies, Turkish foreign policy makers will need to consider this as the most important factor, especially at a time when Turkey is trying to exert influence in the region with its new “zero-conflict with neighbors” policy. The traditional balance of power presupposes increased tension between any two powers competing for influence over satellite states of the Caucasus and Central Asia. As a result, any major Turkish challenge – real or perceived – to US or Russian interests in the region, especially without establishing alliances with regional states, will create tensions between Turkey and these two countries.

Russia is exploiting its comparative advantage in energy resources and export routes to limit US and EU involvement in Central Asia and the Caucasus

As Robert Kaplan of the Center for a New American Security remarked, the US projection of power into Afghanistan and the rising tensions with Russia over Georgia in 2008 in the Caucasus and Central Asia have, to some extent, validated the argument that the Caspian region is the most important land to control in the world today. As a result, tensions can arise not only amongst the major powers but also between major powers and other regional powers as they all try to exert influence in the region.19 The legal complexity surrounding the status of the Caspian as to whether it constitutes a sea or a lake is also a claim of ownership for the resources and has been accompanied by a military build-up, furthering distrust between the states in the region.20 The growing interest of Western powers further encourages the potential for regional conflicts. Such fierce competition sheds light on the dichotomous nature of geopolitical dynamics of the region, especially what some have called the “New Great Game”—a new era of competition between Russia and the United States.

Ariel Cohen, a foreign policy analyst from the Heritage Foundation, a conservative policy organization, endorses such a dichotomous analysis of US-Russian energy relations. According to Cohen, Russia is exploiting its comparative advantage in energy resources and export routes to limit US and EU involvement in Central Asia and the Caucasus.21 He points to the leadership of Vladimir Putin, first as president and now as prime minister, as the reason for Russia’s assertive efforts on the world stage. Similar to Kaplan’s argument regarding the regional competition mentioned above, Cohen further attributes the Russian-Georgian military conflict of 2008 to commercially motivated interests. For him, “Russia’s war with Georgia was as much about preventing additional oil and gas pipelines from being built outside of Russian control as Moscow’s plans to annex South Ossetia and Abkhazia.”22

The United States failed to implement successful policies to balance Russian power in the region in an effective fashion as the Russian dominance in the region is currently at its height

On August 8, 2008, Russian forces invaded the autonomous territory of South Ossetia and engaged in warfare in Abkhazia, a Georgian-occupied territory. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev defended Russian intervention as a move towards the protection of South Ossetia—many of whom are ethnic Russians—against Georgian aggression, thus invoking ethnicity. The war between Georgia and Russia lasted a mere nine days but it demonstrated the bellicosity of Russia’s recent rise in international relations. Beyond its regional context, the conflict ignited a global policy debate concerning the stability in the region and the commercial interests of Russia and the West. Although the only exchange of fire was between Georgian and Russian troops, rhetoric and oppositional diplomatic groups ranged from NATO to the EU and even the US presidential candidates at the time, Senators Barack Obama and John McCain. Therefore, a single regional conflict in the South Caucasus served to simultaneously implicate several parties from the world stage. The sudden involvement of the diplomatic world is not surprising. Europe views Georgia as essential to its Transportation Corridor Europe-Central Asia (TRACECA) program, devised to diversify supply routes. Some, therefore, view Russian aggression as attempting to weaken such initiatives by returning to the revisionist policies of the Cold War era.23

The quick intervention of the US and Western parties in the Russian-Georgian conflict illustrates the urgency with which they view instability in the Caucasus as destabilizing to their security needs. Georgia, as host to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, is an important transit state for energy and thus serves as a deterrent to the Russian monopoly in energy supply from the Caspian. The US and EU strategy has been to underscore the significance of this point.24

It is arguable, though, that the United States failed to implement successful policies to balance Russian power in the region in an effective fashion as the Russian dominance in the region is currently at its height. Most oil pipelines run through Russian territory, giving Russia the benefit in wielding influence. “Georgians,” as well as other states in the region, “have good reason to fear the ambitions, and the wrath, of a rejuvenated Russia seeking to regain lost power.”25 A renascent and bellicose Russia is not only a challenge to US interests but also to others. This brings us back to the argument that suggests that the territorial integrity of the contiguous borders of Russia is as salient in securing peripheral channels for energy transport from the hinterland as ever. Mackinder’s linkage of strategic resources to foreign policy objectives is an argument tied to an inherited conventional belief in the rivalry of East vs. West competition.

Russia is interested in increasing the dependence of the EU on Russian energy exports and thus securing the extension of Gazprom throughout the Caspian. This strategy would ensure the formation of a Russian-led energy cartel

Cohen suggests that Russia’s actions vis-à-vis Georgia were an attempt to stop the expansion of the US presence in a region that Russia considers its “zone of privileged influence” for the transport of goods and energy in what some see as the east-west transport corridor. He underscores his assertions with the facts that the Kremlin benefited from rising oil prices since 1999, moved to nationalize Yukos, the most Western-oriented publicly traded oil company in Russia, and briefly stalled the flow of natural gas to the Ukraine and the EU in early 2009. Simply put, Russia is a global player in the energy markets and has a vested interest in preventing any other power from increasing its “sphere of influence” in the region. Russia’s proximity to the region, as well as the historical clout it has over the regional states in political, military and financial arenas, helps Russia in exploiting its relative energy advantage to assert a monopoly on Central Asian resources and transport routes. In addition to creating this monopoly, Russia is also interested in increasing the dependence of the EU on Russian energy exports and thus securing the extension of Gazprom, a semi-private Russian corporation, throughout the Caspian.26 This strategy would ensure the formation of a Russian-led energy cartel. Assuring the dependence of the EU on Russian energy sources would increase its bargaining power towards NATO, thereby endowing Russia with increasing power in the international arena.

Shams-Ud-Din disagrees with Cohen’s analysis about the “great power politics” in the emerging geopolitics of Central Asia and instead argues that the current political climate involves new players of different political characteristics and with motivations far different from that of imperial Russia and Great Britain. An overemphasis on American-Russian relations would leave out increasingly powerful regional leaders and thus skew any discussion of the geopolitical model too much to the historical side. For Shams-Ud-Din, a new geopolitical model should integrate multiple players in the new “power game” for Central Asian influence because while high politics and the assumptions of economic colonialism are still relevant, low-politics, including the interests of some regional powers to provide opportunities for certain multinational companies (MNCs), is as equally important.27 States are not the only political units with economic interests. The contest for control of energy sources encompasses national politics as well as multiple interested parties, thus making it a pluralistic game better defined by low-politics. “Low-politics is about creating niches of influence in Central Asia by neighboring countries” argues Shams-Ud-Din.28 As a result, many MNCs are as important in the race to acquire stakes in oil exploration, refining, and processing in the Caspian basin. Therefore, it is not only the US that will appear to challenge Russia. Other possible contenders will be Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, India, and China. This low-style of politics will have a crucial strategic influence in the nature and scope of today’s Great Game in the Caspian and will be qualitatively different than the zero-sum game mentality of the early 19th century Great Game.

The US cannot risk losing friends in the region and a broad dialogue on the Caspian with not only India and Turkey but also with Iran and Pakistan is needed

More pragmatic approaches to policy options in the region are also offered. Martha Olcott from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) argues that the large role of Russia in the region, both historically and contemporarily, requires the US to practice a diplomacy that accepts the historic geopolitical legitimacy of Russian interests as a given hindrance to outside actors.29 This perspective is rooted in the fact that a decade of US support for pipeline diversification has not really slowed the development of Russian influence in the region. On the contrary, such a policy has only served to antagonize Russia. The only success of the US policies is the BTC oil pipeline and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) gas pipeline. Much of the region still remains under the security umbrella of Russia, the most powerful actor in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).30 Olcott further argues that, militarily, Russia has already won the fight for the containment against NATO. Russia’s successful defeat of Georgia in the brief military conflict has given it the advantage to consolidate more control over Caspian oil. According to Olcott, the alternative strategy for the US to counter Russian influence rests in enforcing a security partnership of its own in the region. In other words, the US cannot risk losing friends in the region and a broad dialogue on the Caspian with not only India and Turkey but also with Iran and Pakistan is needed.31 This diplomatic approach would force Russia to collaborate with the US and in effect secure American legitimacy with Central Asian leaders.

The US and Europe can only claim to have been influential in establishing the BTC pipeline and by having shares in the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC). CPC was initially created by the Russian, Kazakhstani and Omani governments to build a dedicated pipeline from Kazakhstan to export routes in the Black Sea. Additional companies, including Chevron, Mobil. LUKoil, Royal Dutch Shell, Rosneft (in 1996) and BP (in 2003) – joined the consortium in later years. Today, Russian ownership of the CPC consists of a 44% stake, with Western companies holding the remainder. In addition to creating security challenges, Russia’s power ventures beyond the West’s preoccupation with geopolitics. The Kremlin, led by Vladimir Putin, is fast becoming the central player in changing the focus of Russia’s politics from geopolitics to geo-economics. Putin’s strategy is as domestically oriented as it is internationally focused. He understands that geography, when coupled with the political economy of the state, brings the domestic and the international into a complex web of policy initiatives that eventually renders economics inseparable from state power.

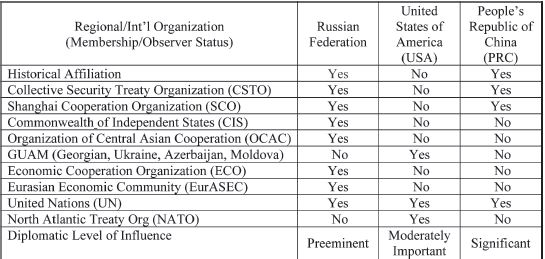

In fact, Vladimir Putin has had intentions to reorganize Russia’s energy advantage to enhance the profitability of the state and its strategic interests.32 Strategic resources, such as natural gas and oil, are subservient commodities, meaning they serve the national interests by fueling the political power of the state. In this context, Putin employs nationalism as the driver of an energy/foreign policy as was seen in the Russian-Georgian war in 2008. Putin’s organization of foreign policy renders external relations endogenous to internal matters, making foreign policy a subcomponent of the domestic glory of his country.33 In contrast to the American or European policy towards the Caspian, Putin presents a more united and assertive front. He is actively engaging international organizations as the façade of his foreign policy. Prominence in the CIS, CSTO, or the Shanghai Cooperation Organization ensures that Russia has the international wherewithal to negotiate its policies with the Caspian states. In this manner, he projects diplomacy with a domestic purpose but legitimizes it through international means.

In comparison, the US attempts to do the same have not been as effective. Despite a close alliance with Georgia and the presence of American military personnel in the region, the US could not back its rhetoric against a resurgent Russia. The invasion of Georgia took place in spite of strong opposition from the EU and NATO. While Russia has yet to reemerge as strong as it used to be militarily, the country is arguably playing by the playbook of Mackinder. Putin’s agenda reflects a willingness to deploy military power with the guarantee that its influence on European energy markets would give it political advantage. What Russia accomplished in the process is the ability to condition political power through geographical means. That is, Russia managed to exploit its military options knowing that its geostrategic hold on Central Asia and the Caucasus meant that energy dependent states would have few options to deter it.

The close proximity of a powerful state like Russia next to weak but pivotal regions like the Caucasus and Central Asia rationally calls for policies with intent to protect its geostrategic interests. In other words, the Russians view Central Asia as their backyard because it essentially provides resources for Russia’s markets and power to assert influence in world affairs. It is therefore not surprising that two years following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia began to integrate Central Asia and the Caucasus in its sphere of military and political influence. This led to the formation of the CIS and with an aggressive diplomatic effort, an agreement on collective security was signed at the fourth CIS summit in Tashkent in 1992. In keeping Central Asia in its military-political sphere of influence, Russia acted on fears that the US advocacy of democracy in Eurasian politics was an effort to dismantle its economic advantage in the region (see Table 2 below).34

Table 2. Great Powers in Central Asia

Russian policymakers refer to Central Asian affairs as their “near abroad” policy—presupposing an historical hegemonic position in the region. Russia’s historical relationship with Central Asia has predetermined its comparative advantage over the West. One case in point is the latest expulsion of the US military presence in Kyrgyzstan in 2009 and Uzbekistan in 2005. Both countries are of geostrategic importance to the US. Yet, Russian officials have strategically managed to bring the two countries closer to its sphere of influence. Moscow asked Kyrgyzstan to expel the US forces in early 2009. 35 It was only after heated negotiations and the US decision to increase the annual rent to $60million for its use of the Manas base near the Kyrgyz capital that the Krygiz leaders allowed the US to stay in the country. News analysis has framed the debate over US troops in Kyrgyzstan as a tacit but assertive Soviet petro-political tactic meant to contain US and Western influence.36

Russian fear of American meddling in the region’s affair is a rational concern. As early as 1992, the US declared that the prevention of “the emergence of any potential future global competitor as one of its dominant foreign policy goals.”37The Caspian’s vast oil reserves are almost on par with Iraq, another center of energy importance to the US. In addition, Georgia plays an important role in securing energy exports from the Caspian. The US suspicion of the Russian monopoly drove the construction of the BTC pipeline by the US and its allies in 2005. The pipeline, notes the New York Times, threatens Russia’s dominance in the region’s energy market.38

The pipeline is perhaps the greatest American achievement in the region regarding energy security. The pipeline bypasses Russian territory and transports oil from Central Asia, effectively reducing Western dependence on the Middle East.39 The American strategy of “happiness is multiple pipelines” is confrontational and directly correlates with the Heartland’s theoretical emphasis: put a wedge between Russia and the Central Asian countries. The pipeline therefore represents the Clinton Administration’s signature effort to weaken the Russian monopoly. However, as Russia is emboldened by increasing petrodollars in the market, the political success of such strategy is not promising. Cliff Kupchan, an analyst for the Eurasia Group, told the New York Times that “the hostilities between Russia and Georgia could threaten American plans to gain access to more of Central Asia’s energy resources at a time when booming demand in Asia and tight supplies helped push the price of oil to record highs. Moving forward, multinationals and Central Asian and Caspian governments may think twice about building new lines through this corridor.”40

In all circumstance, the American strategy is not only hoping to circumvent Russia’s influence, but it is also interfering in Russia’s historical relations with the CAR. Most analysts understand why such a policy would antagonize Russia. Georgia’s vulnerability lies in its alliance with the West; a relationship the Kremlin considers a threat because of the historical enmity between Russians and Georgians. The conflict is rooted in that history. The conflict was and still “is an outgrowth of Russia’s fears that Georgia, with its pro-Western bent, could prove to be a lasting competitor for energy exports.”41

Russia’s motives, while more assertively defined, are similar to those of the US—power, influence and security.42 The Kremlin’s assertive push for control is historically rooted, thereby supplementing an explanation for Putin’s nationalistic outlook. Since the 19th century Great Game, the political interests of Russia have always tied its economy to the region, making Central Asia the hub of Russian power and of considerable geostrategic importance to its relations with the West. The US, on the other hand, is just beginning to develop a central policy for a region in which it is foreign. Its promotion of democratic institutions serves to lessen the historical Russian influence in order to secure the Caspian as the alternative to Middle Eastern oil.

Opportunities and Challenges for Turkish Foreign Policy

Historicizing Russia’s relationship with the region shows a need for a pragmatic foreign policy that understands the competition beyond a zero-sum mentality. Russia already has considerable influence that is both historically rooted and currently stronger than any other external actor, including that of the US. In recognition of this, a pragmatic and less ideologically oriented approach promises the safest route to a policy of competition that does not necessarily have to adhere to the Hobbesian perspective. The situation calls for multipolarity, especially in an environment where Russia utilizes international treaties and organizations to exert its power. The traditional framework of balance of power should diverge away from simply geostrategic competition to include geo-economics. That is, regional actors and the US should begin to devise for themselves new roles as participants in Central Asian energy and security issues, rather than as authoritative parties. Emphasizing equal participation would improve US relations with others in the region, albeit in the midst of Russian opposition.

Immediately following their independence, Turkey launched a number of policy initiatives in Central Asia. Over the years, successive governments have sent delegations to these countries for cultural, economic and political reasons. In time, Turkey’s expectation to play the “big brother” with the possible intention of reviving either the old pan-Ottomanist ideology or a union of the Turkic-speaking states in the region was modified due mainly to (1) Turkey’s position in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, (2) increasing suspicion and doubt of regional states about the real intentions of Turkey, (3) ongoing competition for spheres of influence not only by the US and Russia but also other major regional actors such as Iran, and finally (4) the war in Afghanistan.

Turkey’s traditional avoidance in getting involved more forcefully in regional politics in Central Asia and the Caucasus is in need of rethinking

In this regard, the rivalry between Iran and Turkey in trying to create regional dominance is noteworthy. This rivalry is, however, more than about only energy security. The ideological dimension of the Iranian-Turkish competition certainly has proven to be advantageous for Turkey as the US and the Western European powers do not have the same degree of political, economic and military cooperation with Iran. In response, Russia and China have supported Iran at least since the late 1990s. In a sense, this particular competition is not one of Turkey and Iran alone but it illustrates the great power politics in the region. In fact, neither Iran nor Turkey has the necessary capability to become a true regional power without support from others. The US and the West is concerned that Iran may attempt to radicalize Muslim states in the region and therefore support (and are in need of) Turkey, while Russia and China associate increasing Turkish influence with growing Western power in the region, and as a result, have close relations with Iran.

Given the above discussion, we argue that Turkey’s traditional avoidance in getting involved more forcefully in regional politics in Central Asia and the Caucasus is in need of rethinking. Possible American military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2011 (based on President Barack Obama’s “New Afghanistan Strategy” of December 2009) necessitates the US looking to rebuild the strategic alliance with Turkey, despite the fact that Turkish-US relations have taken a downward turn since the March 1, 2003 decision of the Turkish parliament to not allow American troops to invade Iraq through Turkey. However, for Turkey to ensure the revitalization of this strategic alliance, Turkish foreign policymakers must be ready to take a pragmatic (read: realist) rather than an ideological approach in their actions vis-à-vis the region. In other words, a new emphasis on revitalizing pan-Turkist or pan-Ottamanist, or a new emphasis on the “unity of Muslims”, should be avoided. Policy choices that were unsuccessful in the 1990s are destined to fail again given (1) the importance of the region for the energy needs of both the developed and the developing nations around the world, (2) the US interest in diminishing its reliance on Middle Eastern oil as much and as soon as possible, and (3) the continuation of Russia’s influence in the region and its aim to make the West European states more dependent on oil received from and through Russia.

In our view, in order to carve out an important role for itself in Central Asia and the Caucasus, or the “Heartland” as Mackinder suggested, Turkey should conceptualize the area in the framework of the “Greater Middle East Region,” a concept that was consistently used by the Bush Administration in 2000-2008 in an effort to link US activities in the Middle East with increasing US involvement in Central Asia and the Caucasus. This new conceptualization of the region may help Turkey’s efforts to transfer the “good neighborhood policy” that is currently being implemented in the Middle East to Central Asia and the Caucasus without antagonizing the US or unnecessarily provoking Russia. The emphasis, however, should be on pragmatism and realism more than the ideological significance of this policy as Turkey’s “opening” to the Middle East since 2002 is usually associated with the coming to power of the Justice and Development Party(AKP). Second, although Turkey’s interests will be better served as an ally of the West, and particularly the US, mainly due to historical distrust and minimal political cooperation with Russia, Turkey must still show determination against any single party’s complete control over the region. Therefore, Turkish foreign policymakers should use effective diplomacy to create cooperative arrangements with Central Asian and Caucasian states. Finally, we argue that Turkey must take a more active role in the unresolved conflicts in the region. The AKP government has been active, though not always successful, in mediating crisis-like situations in Iraq and between the Palestinians and Israelis. In contrast, the government developed no strategic or tactical “mediation” policy toward Central Asia or Caucasus.

Endnotes

- Michael T. Klare, Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001), p. 39.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), “Environment and Security: Transforming Risks into Cooperation: The Case of the Eastern Caspian Region, retrieved April 5, 2010, from www.envsec.org.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2008), retrieved April 5, 2010, from http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/Centasia/Background.html.

- Energy Information Administration, “Caspian Sea Region: Survey of Key Oil and Gas Statistics and Forecasts”, retrieved April 6, 2010, from http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/caspian_balances_files/sheet001.htm.

- A. Bernard Gelb, “CRS Report for Congress: Caspian Oil and Gas Production and Prospects,” The Library of Congress for the Congressional Research Service (2009), p. 1.

- Energy Information Administration, Caspian Sea Region: Survey of Key Oil and Gas Statistics and Forecasts (July, 2006) from the EIA, International Energy Outlook 2006 (June, 2006), retrieved October 21, 2009, from http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/ieo/index.html.

- Klare, Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict, p. 42.

- Energy Information Administration, Caspian Sea Region: Survey of Key Oil and Gas Statistics and Forecasts.

- Energy Information Administration, International Energy Outlook 2006 (June 2006).

- James P. Dorian, “Central Asia: A Major Emerging Energy Player in the 21st Century,” Energy Policy, Vol. 34, No. 5 (March, 2006), p. 544.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), “Environment and Security: Transforming Risks into Cooperation: The Case of the Eastern Caspian Region,” pp. 22-24.

- Dorian, “Central Asia: A Major Emerging Energy Player in the 21st Century,” p. 544.

- Asian Development Bank, “About the Central Asian Region”, retrieved April 5, 2010, from http://www.adb.org/Carec/about.asp, p 4.

- “About the Commonwealth of Independent States”, retrieved October 29, 2009, from http://www.cisstat.com/eng/cis.htm.

- H. J. Mackinder, “The Geographical Pivot of History” The Geographical Journal, Vol. 23. No. 4 (April, 1904), pp. 421-430.

- H. J. Mackinder, Lecture at the Royal Geographical Society (London: Great Britain, 1893).

- Mackinder, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” pp. 421-437.

- Michael T. Klare, “The New Geopolitics of Energy,” The Nation, Vol. 286, No. 19 (May, 2008), p. 18.

- R.D. Kaplan, “The Revenge of Geography People and Ideas Shape World Events, but Geography Still Determines them. To understand the coming struggles, all you need is a map of Eurasia and the insights of the Victorian thinkers who understood it best”, Foreign Policy, No. 172 (2009), pp. 96-105.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), “Environment and Security: Transforming Risks into Cooperation: The Case of the Eastern Caspian Region, pp. 19-23.

- Ariel Cohen, “Russia and Eurasia: A Realistic Policy Agenda for the Obama Administration,” The Russian and Eurasian Policy Project, Special Report No. 49 (March 27, 2009), pp. 1-3.

- Cohen, “Russia and Eurasia: A Realistic Policy Agenda for the Obama Administration,” p. 1.

- James Traub “Taunting the Bear,” The New York Times, August 10, 2008.

- B. Martha Olcott, “The Caspian’s False Promise,” Foreign Policy, No. 111 (Summer, 1998), pp. 94-113.

- Traub, “Taunting the Bear.”

- Cohen, “Russia and Eurasia: A Realistic Policy Agenda for the Obama Administration,” p. 4.

- Shams-ud-Din (ed.), Geopolitics and Energy Resources in central Asian and Caspian Sea Region (New Delhi: Lancers Books, 2001), pp. 330-332.

- Shams-ud-Din, Geopolitics and Energy Resources in Central Asian and Caspian Sea Region, pp. 339-340.

- B. Martha Olcott, “Summary: A New Direction for U.S Policy in the Caspian Region.,” In the Series: Foreign Policy for the Next President, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (February, 2009), pp. 1-3.

- Olcott, “Summary: A New Direction for U.S Policy in the Caspian Region,” pp. 1-3.

- Ibid, pp. 2-4.

- B. Martha Olcott, “Vladimir Putin and the Geopolitics of Oil” presented at James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy in 2000s. The Energy Dimension in Russian Global Strategy and the Influence of Russian Energy Supply on Pricing, Security and Oil Geopolitics (Houston: The Baker Institute, Energy Forum, 2004), retrieved October 29, 2009, from http://www.rice.edu/energy/publications/russianglobalstrategy.html.

- Madeleine Albright, “On the Leadership of Vladimir Putin” Time Magazine, April 30, 2009.

- Maxim Shaskenkov, “Russia in Central Asia: Emerging Security Links,” in Ehteshami, Anoushiravan (ed.), From the Gulf to Central Asia: players in the New Great Game (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1994), p. 173.

- Ellen Barry, “News Analysis: Russia Offers Kind Words, But Its Fist Is Clenched,” The New York Times, February 5, 2009.

- Barry, “News Analysis: Russia Offers Kind Words, But Its Fist Is Clenched.”

- Olcott, “The Caspian’s False Promise,” pp. 94-113.

- Jad Mouawad, “Conflict Narrows Oil Options for West,” The New York Times, August 13, 2008.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rosemarie Forsythe, The Politics of Oil in the Caucasus and Central Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).