Since the fall of the former Soviet Union (USSR), Eurasia has emerged once again as the “geographical pivot of history” in calculations of the 21st century’s ‘great game of geopolitics,’ which is played by Russia, China and the U.S., as well as by some other regional powers like Turkey, Iran, India, Japan and South Korea. Grand theorists and strategists from Mackinder to Mahan and from Brzezinski to Dugin have all designated Eurasia as the “heartland” of the “world island” given the importance of its geopolitical landmass and geo-economic potentials. In their common understanding of politics, “whoever rules the heartland, would also rule over the world.”1

As for Turkey, the geographical term of “Eurasia” has frequently referred to post-Soviet Turkic republics (of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan) with the promotion of the well-known ideology of Pan-Turkism (and/or Turanism) among Turkish intellectual circles and policymakers.2 The revival of a neo-Pan-Turkism under the auspices of the then president Turgut Özal steadily increased Turkish public awareness regarding common historical, linguistic, cultural and religious affinities with the peoples and states in post-Soviet Central Asia and the Caucasus. Therefore, Turkey’s relations with Central Asia have been since then discussed and explained with the affinities of Turkic roots and cultural interactions in the wake of the fall of communism.

However, the excessive usage of the rhetoric of Pan-Turkism has created some questions of rationality in Turkish foreign policy, which usually underestimated interior dynamics of the regional polity as well as its lack of effective instruments.3 Even though Ankara’s pragmatic policies seemed to have shown some successes in promoting the “Turkish model,”4 they were nevertheless not sufficient to overcome conventional Russian reserves in the region because of their ephemeral character at that time. Such idealism swerved Ankara into cul de sacs of the basin where the militant realism of international relations has been shaping regional and international politics. Consequently, Turkey’s relations have gone awry with some of the regional actors, first and foremost with Uzbekistan,5 the region’s most populous country and geopolitically one of the most important countries.

Turkish-Uzbek relations have tumultuously undergone a crisis in the course of time mostly due to misunderstandings and mismanagements in mutual relations

In this context, this commentary will briefly deal with the significance of Uzbekistan for Turkish foreign policy that until now has failed to settle an intended partnership with Tashkent. It generally assumes that Uzbekistan is one of the key actors, besides Kazakhstan, which can help Turkey to reintegrate with the region in the next decade. In this way, this analysis suggests that Ankara should accelerate bilateral relations with Tashkent in the new era in which mutual understanding and regional cooperation would be essentially beneficial for both Turkey and Uzbekistan. In doing so, I will attempt to answer the question as to which areas of cooperation can be focused on, in order to resuscitate a long-neglected partnership with Uzbekistan, a country that is still trying to overcome hardships of the power transition in its domestic and foreign policies under a new leadership.

Turkey and Uzbekistan: What Went Wrong?

In the mood of the aforementioned pan-Turkish euphoria during the dissolution of the USSR, Turkey was the first country to recognize the independence of Uzbekistan on December 16, 1991. By the very beginning, bilateral relations were set fraternally and confidence-building measures acquired through the signing of the Treaty of Eternal Friendship and Cooperation on May 8, 1996. Yet, the Turkish-Uzbek relations –contrary to expectations– have tumultuously undergone a crisis in the course of time mostly due to misunderstandings and mismanagements in mutual relations.

The first serious crisis erupted during the early 1990s when Uzbekistan’s post-Soviet leader Islam Karimov’s political opponents took refuge in Turkey together with other Uzbek dissidents.6 The founder of the Erk (Power) Party, Muhammed Salih, who ran a presidential bid against Karimov in 1991, and the chairman of Birlik (Unity) Party, Abdurrahim Polat, were welcomed by the Turkish leadership when they were forced to flee from Uzbekistan in 1993. As Karimov asked President Özal to extradite these people, the Turkish government only decided to expel them from Turkey but refused Tashkent over their extradition. Upon the incident, the Karimov regime immediately called nearly 2,000 Uzbek students, studying in Turkey, back to Uzbekistan. Following this first diplomatic shock, Karimov took Uzbekistan away from any symbolic ideals of pan-Turkism as he failed to join the Summits of the Turkic Speaking Countries mostly because of the nationalist, if not the expansionist, agenda of those meetings.7

The geopolitical outlook of the region in general and Uzbekistan in particular, indicated that Ankara should restore its relations with Tashkent as soon as possible

Ever since, Karimov chose to maintain Stalin’s Soviet nationalities policy regarding the fabrication of a titular Uzbek identity during his more than a quarter-century of patrimonial regime.8 Contrary to the Soviet times, he appealed to the Uzbek history and language rather than communism when he was trying to reinvent glorious past traditions of the age of Tamerlane and his successor Uzbek Khanates.9 Besides that, a politically neutered Islam would either bring back spirituality, which had been destroyed under the Soviet communism, among the Uzbek people, or serve as a tool for the creation of a secular ideology through a state-constructed religion.10

In this regard, Turkey’s laicist system might have been a model for the young Uzbek republic that was striving for the construction of this secular identity through education. But in reality, Turkey’s influence was brought to Uzbekistan by the so-called ‘Turkish schools’ soon after the establishment of formal relations with Tashkent. Founded under the guidance of Fetullah Gülen, who is now a U.S.-based reclusive preacher and businessman believed, by the Turkish state and people, to be the mastermind of the July 15, 2016 coup attempt in Turkey.11

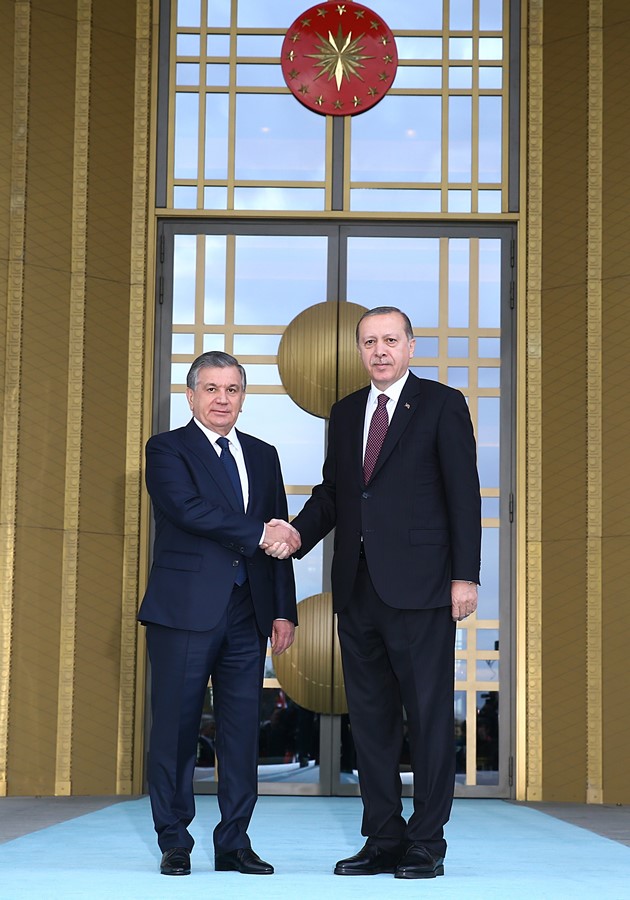

Turkish President Erdoğan (R) shakes hand with Uzbekistan President Mirziyoyev (L) upon his arrival for their meeting at the presidential complex in Ankara on October 25, 2017.

These schools were said to have been spreading the ‘Turkish interpretation of Islam’ in Central Asia.12 Since Gülen schools had ostensibly undertaken the mission of the ‘re-Islamization’ of the post-communist Central Asia at the very beginning, those schools could endanger Karimov’s blueprint modernization project which aimed at forging the new Uzbek identity as well as state cadres in line with the regime’s secular policies.

On the other hand, Uzbekistan’s own radicalization problem based in the Fergana Valley had already created some challenges as members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and other insurgent groups increased their radical presence through violence and terror in and around Tashkent in 1999. In this chaotic atmosphere, Karimov ordered the closure of all Gülen-affiliated schools and institutions in September 2000, as he tightened his grip on power by securitizing the country’s radicalism and insurgency problems.

These schools were frequently promoted by the Turkish leadership from Turgut Özal to Süleyman Demirel and Bülent Ecevit throughout the 1990s in order to spread Turkey’s soft power influences in the region.13 The banning of the schools might be said to have divided the Turkish public and in the subsequent years substantially augmented the already-existing diplomatic rift between Ankara and Tashkent.

Therewithal, a third incident completely strained the relationship in May 2005 when a group of armed gunmen stormed a jail in the Uzbek city of Andijan, located in the restive Fergana region. As Uzbek security forces brutally suppressed the incident and killed several hundred people,14 the issue provoked an international outcry. Then Turkey backed a UN resolution that addressed the Karimov regime’s human rights record and supported some restrictive measures against Uzbekistan adopted by the Council of the European Union.

With the help of unprecedented historical legacy and cultural attraction, Uzbekistan has appeared once again as the “geographical pivot of history” for the Turkic geopolitics today

Turkey’s move caused outrage on the Uzbek side, which accused Ankara of supporting radical groups in Uzbekistan. Afterwards, Karimov refused Turkey’s former President Abdullah Gül’s initiatives to repair the ties and declined to join the newly-established Turkic Council in 2009.15 Since then, the parties have decreased the level of diplomatic relations and their top leaders, Erdoğan and Karimov, only met on the sideline of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics in Russia.

Time to Mend Decadent Relations between Ankara and Tashkent

The geopolitical outlook of the region in general and Uzbekistan in particular, indicated that Ankara should restore its relations with Tashkent as soon as possible. On the other hand, the restoration of ties with Turkey will also help Uzbekistan to break its long-lasting isolationism which it inherited from the legacy of a post-Soviet transition under Islam Karimov. Today, Uzbekistan’s foreign policy is stuck between Russia and China, while its moribund economy needs to open up westward. Turkey, needless to say, can play a significant role to mitigate international pressure over Uzbekistan as well as to assist in opening a window to the West and the Middle East. In return, the long-desired rapprochement with Tashkent would also serve Ankara’s reintegration with Central Asia in the new era.

The parties have recently obtained the opportunity to mend their ties after Karimov died in September 2016. Karimov’s former Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev replaced him as the new president of the country by December of the same year. Turkey has long been expecting some diplomatic enthusiasm from Uzbekistan as it wanted to leave the bad old days in the past.16 Ankara’s expectations came true after nearly twenty years of downhill diplomacy when Mirziyoyev visited Turkey on October 25, 2017. On this date, Mirziyoyev and Erdoğan signed the Joint Statement, which paved the way for the rise of a new cooperation, hereby transforming the relations between the two countries to a new strategic level.17

Both presidents at the press conference in Ankara expressed their gratitude and satisfaction with the level of relations which were recovered after two decades of political and economic regression. Erdoğan welcomed the ties as he underlined the fact that Turkey perceives Uzbekistan as a strategic partner in Central Asia,18 while Mirziyoyev described Turkey as “a country which has huge political, economic and military potential and a high reputation in the international arena … a reliable and important partner for Uzbekistan in the international platform...”19 Most recently Erdoğan also visited Tashkent and Bukhara, on April 30 and May 1 of this year, to attend the second meeting of Turkey-Uzbekistan high-level strategic cooperation which produced 25 new agreements between the countries.

The economic potential between Turkey and Uzbekistan can be regarded as the driving force behind relations in the near future

All these trends in the Turkish-Uzbek relations have shown that the parties are now able to improve a high-level of a mechanism similar to those that have already been steadfastly established between Turkey and Kazakhstan. Turkey’s good relations with Kazakhstan can also be a model for Uzbekistan and vice versa. The Turkish-Kazakh relations have smoothly developed so far at the expense of Astana’s strong ties with Moscow and Beijing.20 The Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev, has skillfully managed Kazakhstan’s foreign and domestic affairs since independence and made his country the most developed and stable state in Central Asia thanks to its geopolitical and geo-economic potentials.21 In brief, Uzbekistan is equally as important as Kazakhstan for Turkey, so Ankara will need to keep good relations with both Astana and Tashkent to return and remain in the region as a game-changer at a time when the balance of power is day by day shifting from Europe to Asia.

Uzbekistan’s Geopolitical Prospects in Central Asia: Why Tashkent Matters?

Given the geopolitical importance of Central Asia, Uzbekistan occupies a place of par excellence in the region as it is located at the heart of Transoxiana, namely the historical cradle of Turco-Islamic civilization for centuries with its glorious cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, Tashkent, Khiva and Kokand. Lying on the traditional silk route between East and West, Uzbekistan has also been the center of commercial and economic activities in the region which attracted the attention of great imperial states of the past, such as the Macedonians, Persians, Abbasids, Seljuks, Mongols, Timurids and Romanovs.

With the help of such unprecedented historical legacy and cultural attraction, Uzbekistan has appeared once again as the “geographical pivot of history” for the Turkic geopolitics today. Its central location between Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan geographically renders Uzbekistan as the single most important actor in conflict resolution and maintaining stability in Central Asia.22

In particular, the security outlook of the region shows that without stability in Uzbekistan, Central Asia seems vulnerable to the so-called “three sources of evil,” namely terrorism, radicalism and separatism. Central Asia constitutes inside a regional security complex and each country’s security sectors are much embedded in other states. All efforts to bring peace, stability and prosperity to the region would eventually require a diplomatic collaboration with and the political will of Tashkent.

The increasing threat of terrorism, militancy and insurgency in Uzbekistan’s Fergana Valley, which also stretches between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, has a potential to endanger all regional security complexes, thereby threatening to spread instability and chaos towards the greater Eurasia.23 That’s why, Uzbekistan can easily turn to the focal point of the region’s long-awaited ‘Balkanization process’24 that might also trigger more 'color revolutions' in the future unless basic security needs are fulfilled either by the region’s governments or by international actors operating in Central Asia. The Andijan uprising in Uzbekistan and the Tulip Revolution in the neighboring Kyrgyzstan in 2005, as well as ethnic conflicts between Uzbek and Kyrgyz people in the Kyrgyz cities of Osh and Jalal-Abad in 2010 have already shown that the region was entering into a more unstable and turbulent period.25

The securitization of terrorist threats has only served for a pretext of maintenance of the autocratic rule of the former president Islam Karimov. Uzbekistan’s new leadership still perceives religious radicalism as the number one security threat to its political stability and/or regime security

On the other hand, Uzbekistan’s economic and natural potential promise a lot for the regional and international powers. With a population of approximately 32 million people, which is also demographically the youngest population in Central Asia, Uzbekistan is comparably a huge market in the middle of the region. Besides, its resource-based economy needs foreign direct investments to achieve a sustainable growth, for which Mirziyoyev’s government launched a massive economic reform program in his first year in office.26

Uzbekistan’s abundant natural gas and gold reserves together with a remarkable amount of uranium and copper deposits in the region is attracting the geo-economic attentions of the developed and developing nations in the world. Last but not least, the country is also known for its tremendous cultivation of cotton, widely known as ‘white gold’ in Central Asia, as Uzbek soils are regarded as one of the most arable and fertile lands for agrarian production in the region.

Under these circumstances, Uzbekistan seems a gateway for the opening up to Central Asia not only for Turkey, but for any great power that is keen to pursue its political, economic and security interests in the region. In other words, whichever country that wants to spread its influence into Central Asia will sooner or later be cooperating with Uzbekistan. Thus, from a geopolitical standpoint, Uzbekistan might be said to have an increased attraction and strength in Central Asia for the predictable future. For this reason, Turkey will have to rejoin the power politics known as the so-called “new great game” in which Uzbekistan constitutes a very central position because of its already mentioned indicators and features.27

Economy as a Catalyst of Turkish-Uzbek Relations in the New Era

Turkey’s economic relations with Uzbekistan were limited mostly due to its broken diplomatic channels during the Karimov era. In addition, the activities of a group of businesses which were linked with the economic branch of FETÖ,28 known as TUSKON (Confederation of Turkish Industrialists and Businessmen), led to further disputes between the countries in recent years.29

After Mirziyoyev’s visit to Turkey, the parties seem to have solved most of the divergences and both governments have pledged to deepen the ties in the economic spheres. Henceforth, the economic potential between Turkey and Uzbekistan can be regarded as the driving force behind relations in the near future. Accordingly, Ankara and Tashkent need to increase investments and transactions by further boosting trade volume, which was already about $1.24 billion as of 2016, with nearly 500 Turkish companies operating in Uzbekistan.30

Turkey is now the fourth biggest foreign trade partner of Uzbekistan and the two countries have already committed to increase the trade volume to a $5 billion in the medium term. To this end, both government envoys signed $3.5 billion worth of commercial agreements within the framework of the first Uzbek-Turkish business forum held in İstanbul during Mirziyoyev’s visit.31 Erdoğan hailed the economic relations when he attended the second Uzbek-Turkish business forum in Tashkent during his recent visit, saying the trade volume had increased 20 percent in the first quarter of this year.32

At present, Uzbekistan urgently needs to boost its economy via foreign capital, including more Turkish investment, as the country’s economy continues to suffer from a currency crisis and high unemployment rate. The Uzbek government is now able to succeed in the implementation of structural reforms launched by the incumbent government in order to eliminate the side effects of the so-called “Russian economic model” of the post-Soviet transition. So far, this model has damaged the Uzbek economy which was crippled by the massive intervention of the state during Karimov’s rule.

Uzbekistan’s own geopolitics today requires it to integrate with the Turkic realm for the sake of the country’s realpolitik in a turbulent region

As a way to cope with problems in the economy, the Uzbek government has recently resorted to ease restrictions in the tourism sector. Thus, it simplified its visa policy for 39 countries in February by completely lifting all tourist visas to seven countries, including Turkey.33 Uzbek authorities are now expecting to host a hundred thousand Turkish tourists annually as they also called entrepreneurs to invest in Uzbekistan.34 A visa-free regime with Uzbekistan also means a lucrative business for Turkish investors who are very enthusiastic to return to the Uzbek market. In line with these aims, Turkish Airlines augmented a number of flights to Tashkent, while it also launched direct flights between İstanbul and Samarkand.

Turkey’s proposed economic partnership with Uzbekistan would be a panacea for the new government that seems keen to ameliorate its bilateral relations with Turkey. The current economic crises in the West also forces Turkey to closely work in this new period to create an economic center of gravity in resource-rich Central Asian economies. The Uzbek government has been seeking to diversify its commercial networks beyond China and Russia for the maximization of its agrarian profits. In addition, both countries are considered as main components of the Chinese-led new silk route initiatives between East-West energy and transportation corridors, which will require an enhanced economic partnership in Asia in years to come.

Security Agenda of the Relations Entails More Cooperation

The normalization of relations between Ankara and Tashkent is not only a requirement of a commercial partnership, but it is also a necessity of security cooperation, which the parties will have to counteract against increasing terrorism threats. Uzbekistan and Turkey are the two countries which have suffered much from terrorism for decades. The challenge of religious radicalism in Uzbekistan, and Turkey’s vulnerability to PKK’s ethnic separatism created a convenient setting for terrorist cells in both countries throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

From the Tajik civil war of the 1990s to the American invasion of Afghanistan and beyond, radical militant groups, ranging from Taliban, Hizb’ut Tahrir, the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU) and the IMU to Khorasan, Akromiya, al-Qaeda and the Turkestan Islamic Party, (TIP, previously ETIM), have all stationed in and around the Fergana Valley. These radical militant/insurgent groups recruit new generations against what they claim the “state-crime nexus” with motivations of the so-called, ‘global jihad’ in Central Asia.35

To the present, all these groups have subtly used the chaotic atmosphere of the 9/11 aftermath as they benefited from the conflicts in Iraq, Syria, Chechnya, Libya and Yemen in the Islamic world. The increasing presence of ISIS and al-Qaeda in recent years has further escalated instability and insecurity in the region from where the flow of militancy has been posing terrorist threats elsewhere in the world. Thus, Uzbek militants’ participation and allegiance to those worldwide terrorist organizations, has changed the nature of threat nowadays, from a local dimension to a global one.

Turkey and some Western countries have gradually become the target of ISIS and al-Qaeda terrorists of Uzbek descent, who were trained in Iraq and Syria and launched attacks on civilians. In Turkey, for instance, there have been several terrorist attacks linked with Uzbek nationals in recent years. First and foremost, the bomb attack at the İstanbul’s Ataturk Airport in 2016 that killed 42 people was carried out by three suspects coming from the former Soviet space, including Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. The second terrorist attack which targeted İstanbul’s famous Reina nightclub at the New Year party in 2017, killing 39 people, was also carried out by another Uzbek citizen and ISIS member, Abdulgadir Masharipov.

These two events in Turkey have shown the urgency of terrorist threats coming from Central Asia. In addition, Uzbek and Kyrgyz terror suspects were also involved in similar incidents in the West, such as the truck attacks in Stockholm and New York city centers and St. Petersburg metro bombing in 2017, which were all associated with Central Asian recruits of ISIS and al-Qaeda.

The dimension of threat that these terrorists have posed to the present is huge and seemingly set to continue to challenge Turkey, Russia and the West for a predictable future. In order to preempt all these challenges, Turkey and Uzbekistan will need to cooperate over security issues considering the militant flow, which is also a headache for Tashkent given its decades old struggle with the aforementioned extremist and insurgent groups.

Representatives of Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan attend the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States “Meeting of the Ministers of Transportation” in İstanbul, on March 9, 2016.

In the past, the securitization of terrorist threats has only served for a pretext of maintenance of the autocratic rule of the former president Islam Karimov.36 Uzbekistan’s new leadership still perceives religious radicalism as the number one security threat to its political stability and/or regime security. Mirziyoyev’s government will have to tackle the issue within more realistic methods, which require changes in his strategy for the eradication of this problem from the country’s political and security agenda.

Contrary to two decades of political isolationism under Karimov, Mirziyoyev has so far shown a tendency towards more cooperative foreign and security policies with neighboring countries as well as with international actors and organizations.37 His recent rapprochement efforts with Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan have all indicated to Uzbekistan’s policy changes regarding the region’s long-awaiting inter-ethnic and cross-border security challenges like terrorism, extremism, trafficking, smuggling, migrant influx, separatism, militancy and insurgency.

Undoubtedly, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) would be one of the best platforms to cope with all those problems in Eurasia’s regional security complexes. Turkey is a dialogue partner in the SCO since 2012 and it desires to be a full member inside the security bloc where Uzbekistan is also a key member state. Since Uzbekistan has rejected to participate in the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the SCO has come into prominence as the most important security umbrella for Tashkent. Turkey’s rapprochement with Uzbekistan might provide its accession to the bloc whereas the SCO’s close cooperation with Turkey would also increase its capabilities of counterterrorism.

After India and Pakistan’s full membership last year, the SCO option for Ankara is becoming more essential since most of the non-conventional security threats have been challenging Turkey from its Asian neighborhood. Accordingly, Turkey needs to collaborate with the SCO member states for the sake of its own security as well as for the security needs of Eurasian countries.

Apparently, Ankara’s increasing relations with both Moscow and Astana may facilitate to broaden its partnership with the SCO in years to come. On the other hand, Uzbekistan also emerges as another key political actor, whose recent rapprochement with Turkey may also serve for Ankara’s security needs in the region. In a broader sense, one might assert that a prospective Turkish-Uzbek security alliance would be unavoidable in terms of preventing conventional and non-conventional challenges between Asia and Europe.

Uzbekistan in the Turkic Council: Turkey’s Wish or Geopolitical Reality?

Although the newly independent Turkic states in Central Asia and the Caucasus welcomed Ankara’s support and interests in the region, they nevertheless did not desire Turkey’s proposed ‘big brother’ role after the seventy years of Russian/Soviet example. At the very beginning, the Turkic republics had considered Turkey as an ‘external ally’ despite Ankara’s opening policies which aimed at forming an ethnolinguistic bridge from the “Adriatic to the Great China Wall.”38 As soon as Turkey’s leadership realized the impracticality of those policies, Ankara prioritized non-governmental actors and economic means to open up to Central Asia. But this time, Turkey was not able to succeed what it has envisaged for the region as Russia, China and the U.S. had already filled the power vacuum during the post-Soviet era.

When the ruling AK Party came to power in late 2002, Turkey’s foreign policy efforts were mostly devoted to restoring conventional ties with the Middle East and the EU. The relations with the wider Eurasia have been evaluated in the scope of the new born Turkish-Russian economic partnership. Hence, Turkey’s priorities in Eurasia have been shifted from Central Asia to Russia and the Caucasus when the consecutive AK Party governments led by the then Prime Minister Erdoğan focused on the improvement of commercial and energy ties with both Moscow and Baku.39

In a move to realign with the Turkic world, however, Turkey sealed the foundation agreement of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, known as the “Turkic Council” in brief, together with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Azerbaijan in 2009. The Turkic Council currently has its political and economic limits, but started to promote cultural, educational and communicational exchanges as well as an approximation of common understandings between the member states regarding issues and problems in and around Eurasia.40 Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are also deemed to be potential members of the Council in the future. Their participation would, no doubt, be one step forward to the long-anticipated “Turkic Union,” which Ankara has been eager to materialize since the Soviet break-up.

Beyond the pillars of romantic nationalism of the classical pan-Turkism, the Turkic Council was established on credentials of the Turkic geopolitics in the 21st century. None of the member states mentioned the symbolism of pan-Turkish ideology at the Council, but nevertheless, they accept that the new platform would seek for the interests of the Turkic world in regional and international diplomacy.

Turkish-Uzbek cooperation would be a game-changing move for both sides if this could be materialized in the new era. For these purposes, Uzbekistan needs to maintain its gradual institutional change through a firm political will, whereas Turkey should refresh its enthusiasm to return to the region like it displayed throughout the 1990s

Although it is not a member yet, Uzbekistan’s participation seems very vital for the Council itself and indispensable for Tashkent in the future given the fact that the country straddles in the middle of the Turkic world. The Uzbek government has already pledged to take part in the Turkic Council’s upcoming summit in Bishkek in months to come as Erdoğan and Mirziyoyev discussed the full membership of Uzbekistan, whose flag will be flown in the organization’s office in İstanbul.41

Uzbekistan’s joining in the Turkic Council will definitely ease tensions as it helps to diminish regional disputes with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Contrary to 17 years of low level diplomatic relations with Kyrgyzstan during Karimov, Mirziyoyev visited Bishkek as soon as he took office and addressed the resolution of the most notorious problems like cross-border water sharing and social discontent between Kyrgyz people and the Uzbek ethnic minority living in Kyrgyzstan.

For the time being, the Turkic Council is still a nascent political body, but it has the potential to solve all those trans-boundary problems within a constructive regional diplomacy among its member states. No doubt, Turkey’s membership makes the Council nearly as equal as to Russian-led international organizations in Eurasia, while Uzbekistan’s proposed membership would provide a close cooperation among Central Asia’s landlocked coterminous countries.

Turkey had sought to integrate with the Uzbek Khanate since the times of Suleiman the Magnificent as a necessity of historical reasons and cultural affinities with the geography, which was known as “Turkestan” until the Russian conquest in the 19th century. Uzbekistan’s own geopolitics today requires it to integrate with the Turkic realm for the sake of the country’s realpolitik in a turbulent region. A neo-détente process between Ankara and Tashkent might sooner or later force the parties to form a new partnership under an umbrella organization like the Turkic Council.

Conclusion

Uzbekistan has so far constituted the weakest link in Turkey’s foreign policy in post-Soviet Central Asia, which many experts and analysts regard the geopolitical heartland of Eurasia. Ankara and Tashkent now opened a new chapter to forge a symbiotic relationship under the auspices of both presidents Erdoğan and Mirziyoyev. Yet, the parties need to maintain the political will, which has been put forward during Mirziyoyev and Erdoğan’s reciprocal visits, in different areas to clinch the long-anticipated Turkish-Uzbek partnership in years to come. Those areas consist of economy, energy, tourism, culture and security as well as diplomatic cooperation regarding regional and international issues.

From now on, the new Uzbek leadership will have to maintain stability and security as well as the need to reinvigorate a stagnant economy in Central Asia’s most turbulent country that makes it also geopolitically the most significant one in the region. At this point, Uzbekistan’s rapprochement with Turkey would revitalize both countries’ aims and interests in Central Asia where Ankara and Tashkent have been acting as passive-by-standers contrary to their real political, economic and military parameters and potentials.

Therefore, as this analysis has suggested, Turkish-Uzbek cooperation would be a game-changing move for both sides if this could be materialized in the new era. For these purposes, Uzbekistan needs to maintain its gradual institutional change through a firm political will, whereas Turkey should refresh its enthusiasm to return to the region like it displayed throughout the 1990s.

However, this time Ankara will be required to build a more rational foreign policy approach that should reckon with regional dynamics and international calculations. On the one hand, Turkey’s developing relations with Russia, China and Iran may facilitate opening of some diplomatic channels for Ankara in Central Asia. On the other hand, Turkey should continue to compete with conventional Russian formal and informal culture and institutions, as well as comparative economic advantages of China in the region. In this vein, Turkey’s soft power instruments like the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) and the Presidency of Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB), will continue to serve for the creation of communication networks, cultural interactions and socio-political awareness between Anatolia and Central Asia, the two corners of the Turkic world.

To sum up, Turkey’s flourishing relations with both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are vitally important, especially at a time when its Central Asian policy has been shaken by the FETÖ affairs over the past several years. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia are the two countries where the remnants of FETÖ still actively operate through their charter schools and whose graduates have been maintaining a lot of power in the high-ranking bureaucracies. On the contrary, Uzbekistan is a safe haven for Turkey in terms of FETÖ cadres since Islam Karimov shut down those schools as early as the beginning of the 2000s.

Endnotes

1. For further reading on geopolitics of Eurasia, see Halford J. Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, (London: Constable Publishers, 1942); Halford Mackinder “The Geographical Pivot of History (1904),” The Geographical Journal, Vol. 170, No. 4 (December, 2004), pp. 298-321; Zbigniew K. Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

2. In order to properly understand the cultural and institutional genesis of Pan-Turkist ideology and its resurrection in Turkey soon after the Soviet collapse, see Jabob M. Landau, Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation, (London: Hurst & Company, 1995).

3. Ertan Efegil, “Rationality Question of Turkey’s Central Asia Policy,” Bilgi, Vol. 19, No. 2 (2009), pp. 72-92.

4. Emre Erşen, “The Evolution of ‘Eurasia’ as a Geopolitical Concept in Post-Cold War Turkey,” Geopolitics, Vol. 18, No. 1, (2013), pp. 26-28.

5. Adam Balcer, “Between Energy and Soft Pan-Turkism: Turkey and the Turkic Republics,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 2 (2012), pp. 153-54.

6. Nadir Devlet, “Turkey and Uzbekistan: A Failing Strategic Partnership,” The German Marshall Fund of the United States, (January 5, 2012), p. 2, retrieved from www.gmfus.org/file/2523/

7. Bernardo Teles Fazendeiro, “Uzbekistan’s Defensive Self-reliance: Karimov’s Foreign Policy Legacy,” International Affairs, Vol. 93, No. 2 (2017), p. 424.

8. See, Charles Kurzman, “Uzbekistan: The Invention of Nationalism in an Invented Nation,” Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 8, No. 15 (Fall 1999), pp. 77-98.

9. Olivier Roy, Yeni Orta Asya ya da Ulusların İmal Edilişi, (İstanbul: Metis Yayınları, 2009), pp. 223-228.

10. Johan Rasanayagam, Islam in Post-Soviet Uzbekistan: The Morality of Experience, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 97-103; Kurzman, “Uzbekistan: The Invention of Nationalism in an Invented Nation,” pp. 88-90.

11. Following the July 15 coup attempt in 2016, Turkey’s National Security Council have designated all institutions, NGOs and people affiliated with Fetullah Gülen as a terrorist organization, dubbed as FETÖ (Fetullah Terrorist Organization), based on concrete evidence which put forward the role of the organization in the quashed coup. The U.S. State Department in its 2016 country report on terrorism (retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/

12. Bayram Balcı, “Fethullah Gülen’s Missionary Schools in Central Asia and Their Role in the Spreading of Turkism and Islam,” Religion, State & Society, Vol. 31, No. 2 (2003), pp. 153-157.

13. Lerna K. Yanık, “The Politics of Educational Exchange: Turkish Education in Eurasia,” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 56, No. 2 (March 2004), pp. 298-302.

14. The death toll was the most controversial issue during the violence in Andijan. The government sources gave the number of people killed in the conflicts around 170, but media reports estimated the death toll to nearly 3,000 people. See, Shirin Akiner, “Violence in Andijan, 13 May 2005: An Independent Assessment,” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, Silk Road Paper, (July 2005), pp. 19-20, full text retrieved from https://www.silkroadstudies.

15. Devlet, “Turkey and Uzbekistan: A Failing Strategic Partnership.”

16. “Turkey Pursues a Reset with Uzbekistan,” Eurasianet, (November 17, 2016), retrieved from http://www.eurasianet.org/

17. “The State Visit of the President of Uzbekistan to Turkey was Fruitful,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan, (October 27, 2017), retrieved from https://mfa.uz/en/press/news/

18. “Uzbekistan Is a Strategic Country in Central Asia in Every Respect,” Presidency of the Republic of Turkey, (October 25, 2017), retrieved from https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/

19. “Mirziyoyev, Erdoğan Hold Joint News Conference in Ankara,” The Tashkent Times, (October 26, 2017), retrieved from http://tashkenttimes.uz/

20. İbrahim Kalın, “Turkey and Kazakhstan: A Relationship to Cherish,” Daily Sabah, (April 17, 2015), retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/

21. Serdar Yılmaz, “The Role of the Leadership of Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan’s Stability,” International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science, Vol. 5, No. 2 (March 2017), pp. 63-69.

22. Svante E. Cornell, “Uzbekistan: A Regional Player in Eurasian Geopolitics?,” European Security, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Summer 2000), pp. 125-126.

23. Hooman Peimani, Conflict and Security in Central Asia and the Caucasus, (California: ABC-Clio, 2009), pp. 15-16.

24. Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, pp. 130-131.

25. Aigerim Zikibayeve (ed.), “What Does the Arab Spring Mean for Russia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus?,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, A Report by Russia and Eurasia Program, (September 2011), p. 4, retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/

26. “A Year of Economic Reforms with President Mirziyoyev,” Voices on Central Asia, (December 28, 2017), retrieved from http://voicesoncentralasia.

27. Markéta Šmydkeová, “Uzbekistan at the Centre of the New Great Game,” Contemporary European Studies, Vol. 1, (2013), pp. 27-49.

28. See note 11.

29. “Uzbekistan: Tashkent Takes Hardline Approach on Containing Turkish Soft Power,” Eurasianet, (April 3, 2012), retrieved from http://www.eurasianet.org/

30. “Relations between Turkey and Uzbekistan,” Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/

31. “Uzbekistan and Turkey to Sign 35 Documents for US$3.5 Billion,” UzDaily, (October 26, 2017), retrieved from https://www.uzdaily.com/

32. Kübra Chohan, “Turkey, Uzbekistan Look to Boost Ties in All Areas,” Anadolu Agency, (April 30, 2018), retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-

33. “Uzbekistan Announces Visa-free Travel for 7 Countries, Simplifies Visa Application for 39,” The Tashkent Times, (February 3, 2018), retrieved from http://tashkenttimes.uz/

34. “Özbekistan, 100 Bin Türk Turist Bekliyor,” Qırım Haber Ajansı, (February 6, 2018), retrieved from http://qha.com.ua/tr/turk-

35. David Lewis, “Crime, Terror and the State in Central Asia,” Global Crime, Vol. 15, No. 3-4 (2014), pp. 339-347.

36. Sebastien Peyrouse, “Does Islam Challenge the Legitimacy of Uzbekistan’s Government?,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 419, (February 2016), pp. 1-5.

37. Richard Weitz, “Uzbekistan’s New Foreign Policy: Change and Continuity Under New Leadership,” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, Silk Road Paper, (January 2018), pp. 9-11, retrieved from http://silkroadstudies.org/

38. Kürşat Çınar, “Turkey and Turkic Nations: A Post-Cold War Analysis of Relations,” Turkish Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2 (2013), p. 257.

39. F. Stephen Larrabee, “Turkey’s Eurasian Agenda,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 1, (Winter 2011), pp. 104-115.

40. Ramil Hasanov, “The Turkic Council: A Strong Regional Mechanism to Enhance Cooperation in Eurasia,” in Fifth Summit of the Turkic Council: A Rising Actor in Regional Cooperation in Eurasia, Centre For Strategic Research (SAM), (October 2, 2015), pp. 1-4, retrieved from http://www.turkkon.org/Assets/

41. “Uzbekistan to Take Part in Work of Turkic Council,” UzDaily, (April 30, 2018), retrieved from https://www.uzdaily.com/