Introduction1

Far right rhetoric and jihadi-inspired terrorist incidents have derailed progress on the minority protection initiatives begun in earnest with the European Year against Racism declared by the European Council of Ministers and representatives of the member states’ governments in 1997. These efforts were intended to reduce disparities and polarizations in Europe by removing barriers to the full participation of minorities in European States.2 The Council of Europe targeted eight key areas of life in its effort to monitor and improve parity between minorities, including Muslims, and those who call themselves “natives” of Europe.3 The key areas are “employment, housing, healthcare, nutrition, education, information, culture and basic public functions (which include equality, anti-discrimination and self-organization).”4 Reducing discrimination remains an elusive goal in this effort, though critical to minimizing minority/majority disparities and utilizing the talents of minorities in Europe. Discrimination predominately targets Muslims, whose conservative lifestyle and overt practice of religion draw unwanted attention in secular Europe, and far right parties have mobilized to deny Muslims a place in European culture.5 The diversity protection initiatives that began twenty years ago are viewed with suspicion by those attracted to the nativism promoted by right wing populist parties. Regardless of Europe’s need for labor and the demographic trough many member-states face, experts’ recommendations for addressing these problems are not persuasive to some in the ethnic majority. Demographers, like the economist-technocrats guiding the European Parliament’s policymaking or advising center-left political parties, face a skeptical audience for their analyses.6 Weakened trust in the state and in European policymakers also instigates a turning away from experts on the part of voters.

Yet quantitative research on Muslims in Europe consistently demonstrates their support for democracy as it is practiced in their European state and their greater approval than non-Muslims of political, judicial and criminal justice institutions.7 Where exceptions to this trend occur, as, for example, in the weaker support for police on the part of Muslims in France, the reasons are clear. Both the French high court and minority protection agencies have criticized the French police practice of routine identity checks of men of color (who are likely to be Muslims) in France.8 Despite their unfair police scrutiny, Muslims in France are as likely as non-Muslims to trust the legal system, as data from the European Social Survey show.9

We can expect then that Muslims will make demands of the democratic agencies in Europe: that they will use electoral and legislative political processes to attain protections and that they will adapt the organization of Islam and its teaching to their circumstances in Europe. It may be that their guest worker or refugee family backgrounds have heightened the appreciation Muslims have for the democratic institutions of their European states, but their expectations of Europe grow with each generation born there. Previously, data from the European Social Survey in 2008 have shown that Muslims born in France or the Netherlands, for example, are at least 15 percent more likely to feel that they are members of a group that is discriminated than other Muslims living in these states but born abroad.10 In this paper, we examine more recent data on Muslims’ attitudes in Europe and consider state-level indicators of their political and policy environments relating to multiculturalism.

Country Selection and Data Sources

Using data from the European Social Survey up through 2014 we look below at evidence of Muslims’ European identification in France, Austria and the Netherlands, including their trust in the political process in the current era of hate speech directed toward them. We also evaluate measures of their perception of the discrimination they experience. We examine these states because, in all three, far right political mobilization stoked anti-Muslim sentiment during the run-up to 2016-2017 national elections for president or prime minister. The Muslim minority was the most salient target of the far right’s anti-immigration rhetoric in each state. The center prevailed in all three nations, but these electoral campaigns further legitimized hostility toward the religious minority and denial of Muslims’ place in European culture.11 Norbert Hofer’s right wing Freedom Party (FPÖ) platform, for example, rallied Austrians against “‘the invasion of Muslims.’”12 Marine Le Pen’s National Front promised France “fewer mosques and less halal meat.”13 Geert Wilders led the Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands, declaring that “Islam and freedom are not compatible.”14

The gap between perceptions of the size of the Muslim population and its reality reflects a general lack of accurate information about Muslims in Europe

Although they represent less than 10 percent of the population in each of these European states, Muslims are perceived to be a greater demographic presence. The 2016 Ipsos MORI Perils of Perception Survey found, for example, that French respondents overestimated the size of the Muslim population there by 24 percent. Muslims composed 7.5 percent of the French population in 2016 but French respondents overestimated their size at 31 percent.15 The gap between perceptions of the size of the Muslim population and its reality reflects a general lack of accurate information about Muslims in Europe. Speculation abounds regarding Muslims’ reactions to being targeted by hate speech. Will they radicalize or use the political system as Europeans to counter the hostility toward them? Muslims have not fully mobilized to vote. Will they do so now? Which parties will court their vote? Will they form new political parties, or join with other Europeans of similar socio-economic backgrounds in established parties?

With data from the Chapel Hill Experts Survey and Banting and Kymlicka’s Multiculturalism Policy Index, we examine the degree to which multiculturalism has been institutionalized in these states, providing a pathway to minority inclusion. The START database on terrorism at the University of Maryland allows us to look directly at the level of jihadi inspired terrorism in Europe. Official reactions to these problems underscore the paradigm shift away from minority protections in Europe and represent a challenge to Muslims. We consider these difficulties and how Muslims in Europe are responding.

National and European Political, Policy and Terrorism Context

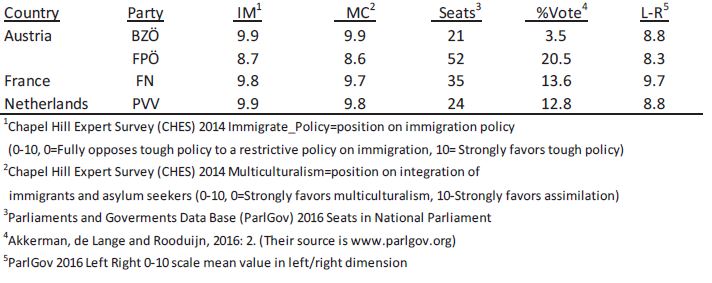

The extent of far right political mobilization in western Europe is reflected in Table 1. While we look specifically at Austria, France and the Netherlands in this paper, the growth of support for right wing agendas is a prominent feature of the political landscape in the other developed democracies of the region and has repercussions for policymaking at the supranational level of the European Council and Parliament.16 Table 1 lists for the three nations on which we focus the stable, electorally successful far right populist parties with a realistic prospect of attaining national office.17 Successful right wing parties are specified for each country in the second column of this table, next to the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) 2014 ratings of their policy positions on immigration and multiculturalism in columns 3 and 4. The number of seats each party has earned in national parliament is indicated in column 5 (taken from the 2016 Parliaments and Governments Data Base (ParlGov)). The percent of the actual vote obtained in national elections between 2010-2015 is provided in column 6.18 In the last column of Table 1, we report the party’s mean value in the left/right dimension (from 2016 (ParlGov)).

Table 1: Support for Right Wing Agenda

A summary look at the table shows that all three of these western European states have stable, electorally successful right wing parties that are fully in favor of restrictive immigration policy (column 3, IM), opposed to multiculturalism (MC, column 4), and scored as right wing by scholars on a left/right dimension scale (column 7, L-R). These figures reflect a fertile backdrop for growing support for far right candidates and their message throughout western Europe.19 The most recent national elections in Austria, France and the Netherlands show that the far right message has taken root.

In Austria, France and the Netherlands, electoral gains by the prominent right wing party provide a basis of credibility from which to pull conservative party agendas toward the right with the threat of voter defections to the far right populist party

Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ) for example, led by Norbert Hofer, earned 46 percent of the vote in his 2016 presidential run-off election loss to Alexander Van der Bellen. Then in 2017, Sebastian Kurz led the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) to the right, winning the election and ultimately forming a coalition government with the Freedom Party in an outcome “feared” by some Muslim leaders.20 Thirty-one-year-old Kurz took anti-immigration positions “ripped from the populist playbook.”21 Some describe such populist successes as votes “not simply against mainstream parties… but against meritocratic elites who have arguably lost touch with their roots” (emphasis ours).22 But, also in 2017, Marine Le Pen lost to Emmanuel Macron in a run-off election for the presidency in France with 33.9 percent of the vote. In the Netherlands, the Party for Freedom (PVV), led by Geert Wilders, won 13 percent of the vote and gained 5 seats, coming in second to the liberal People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD). The PVV “won 5 seats and is the second largest party in the Netherlands with 20 seats,”23 but did not come close to beating the VVD, which remains “the largest party in the country with 33 seats (out of 150).”24 In Austria, France and the Netherlands, electoral gains by the prominent right wing party, though insufficient to propel them to power, provide a basis of credibility from which to pull conservative party agendas toward the right with the threat of voter defections to the far right populist party.

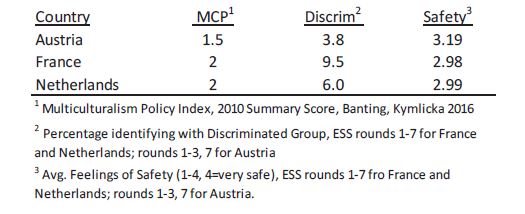

Table 2: Multicultural Orientation, Majority Feelings of Discrimination and Safety

Table 2 demonstrates a low level of institutionalization of multiculturalism in Austria, France and recently the Netherlands as well. The Multiculturalism Policy Index (MCP) 2010 Summary Score in the first data column of Table 2 is based on eight “rights” areas of social policy: constitutional affirmation of multiculturalism, school curriculum, media, exemption, dual citizenship, funding, bilingual education and affirmative action.25 Movement toward multiculturalism on these policies is seen to build solidarity in the state through the accommodation of diversity in public institutions and private places of work. Fully developed multicultural policies in several rights areas yield a higher MCP national score. Each of the three states on which we focus scores at the low end, at 1.5 for Austria, and 2.0 for both France and the Netherlands. These states stand in contrast to other countries whose MCP scores are not shown, including the UK and Belgium (each with an MCP score of 5.5), Finland (at 6.0) and Sweden (at 7), where more areas of multicultural policy are institutionalized. Austria, for example, is scored as having no constitutional affirmation of multiculturalism, but some recognition of cultural diversity at the municipal level. Austria does not have institutionalized dress code exemptions, nor does it promote affirmative action for disadvantaged minorities. France, with a slightly higher MCP score than Austria, permits dual citizenship and some funding for ethnic organizations. The Netherlands’ MCP total score slipped to 2.0 in 2010 (from 4.0 in 2000) largely because of the transformation of the minorities policy to an integration policy, a weakening of the rules for representation of minorities in the media, and reduction in requirements for affirmative action for disadvantaged minorities. Weak institutional support for multiculturalism in these three states does little to bolster the legitimacy of Muslim demands for recognition and fairness in the face of nativist calls for protection of the traditional culture and bureaucratic practices of the state.

Most Muslims in Europe have nothing to do with terrorism, but their non-Muslim neighbors may not distinguish them from the jihadis described in news broadcasts as acting in the name of Islam

Lack of official support for multiculturalism may also inflame the resentment of some toward protections accorded to minorities. The second column of data in Table 2 provides the percentage of majority group members who feel that they are part of a group that is discriminated against: 3.8 percent in Austria, 9.5 percent in France and 6 percent in the Netherlands. Given the efforts by far right parties to mobilize this sense of discrimination on the part of “natives” in European states,26 these percentages are lower than might be expected, though still part of the terrain policymakers and minority group members must traverse in seeking greater accommodation by the system for minorities.27 Similarly, considering the claims by right wing parties that immigrants, asylum seekers and other foreigners drive up a crime, a look at the data in the last column of Table 2 is in order. Majority group members’ “average feeling of safety” score is 3 on a 4-point scale, suggesting that natives in Austria, France and the Netherlands (like those in other European states not shown) feel relatively, but not “very” safe.

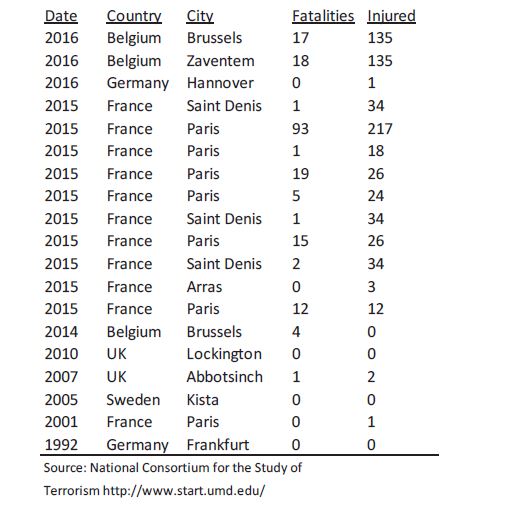

Terrorist incidents in western Europe likely exacerbate the sense of insecurity that accompanies diversity for many. Table 3 lists these events in western European states from 1990-2016. These data were obtained from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) and its Global Terrorism Database.28 All recorded incidents in western Europe known or suspected to have been inspired by al-Qaeda, ISIS and other Jihadi groups are enumerated in Table 3. Nineteen incidents meet these criteria for the 1990-2016 period in western Europe; eleven occurred in France, three in Belgium, two each in Germany and the UK, and one in Sweden. None are listed in the Global Terrorism Data Base for Austria or the Netherlands, but a terrorist incident anywhere in Europe no doubt spreads fear throughout the continent. Fifty-eight percent of these nineteen incidents occurred in France, casting a negative light on the French Republican ideal of civic membership overcoming minority/majority status as the basis of the nation’s social solidarity. Although some of the most horrific terrorist events carried out in France were planned elsewhere, the fact that so many were carried out in France suggests that the divide between French police and the banlieues renders these neighborhoods fertile ground for accomplishing mayhem from abroad.

Table 3: Global Terrorism Database

Most Muslims in Europe have nothing to do with terrorism, but their non-Muslim neighbors may not distinguish them from the jihadis described in news broadcasts as acting in the name of Islam. In Europe’s current political and policy environment, shaken up considerably by recent terrorist incidents, widespread suspicion and hostility face Muslims as they go about their daily lives, earning a living and raising their families. The stressors on Muslims’ identification as Europeans are clear. We look now to see how members of the religious minority are holding up. We offer our evidence-based analysis to test popular, but unsubstantiated assumptions of Muslims’ growing alienation from European state institutions.29

Evidence of Muslims’ European Identification

“A French Islam Is Possible,” declares the title of the Institute Montaigne’s report, drafted by Hakim el-Karoui.30 The study is based on the results of a 2016 survey of “the social practices and opinions of individuals in France who identify as Muslim or come from a Muslim background.” Sampling was guided by quotas calculated from official (INSEE) census data for the population aged 15 and over living in mainland France. The survey data were analyzed by researcher Antoine Jardin at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). Several findings emerging from the data contradict the headlines promoted by right wing populist politicians. First, “despite worries about Islamic separatist tendencies, the ‘Muslim community in France’ is simply non-existent: no sense of belonging, shared interests, or capacity for coordinated action have been identified.”31 Secondly, perhaps explaining the first point, Muslims in France vary considerably in the geopolitical backgrounds of their families reflecting the relationships France has developed and maintained with the countries of North Africa and with Turkey. The collective perspective of French Muslims is therefore more comparable to that of their neighbors in France than to a “Muslim community” imagined by right wing politicians. Third, most Muslims in France have the same priorities for themselves and their families as other French citizens, differing as they do by educational and occupational position. Fourth, in terms of religiosity, 46 percent of Muslims in France are “either completely secularized or approaching full integration into a system of values of contemporary France…”32

As is the case for Austrian and French Muslims, religion is the main source of bias reported by Dutch Muslims followed by nationality

But there is one finding of the Institut Montaigne’s study to which anti-diversity politicians will point as a justification for claiming that Muslims do not belong in Europe: 28 percent of French Muslims

have adopted a system of values clearly opposed to those of the French State. They are mostly young, low-skilled and facing high unemployment; they live in the working-class suburbs of large cities. Rather than being defined by conservatism, this group identifies with Islam as a mode of rebellion… For them, Islam is a means of self-assertion at the margins of French society.33

Paradoxically, this is the group most likely to be influenced toward extremism by right wing political mobilization in their European state. The “rebellious 28 percent” are not spiritual or religious Muslims; rather they are political in their use of Islam as a platform for critique, protest, and sometimes, crime.

Efforts to counter violent extremism must be concentrated both on this group and on their right wing counterparts who use politics as a tool for the marginalization of the religious minority. Regarding those for whom Islam is a political platform, Tareq Oubrou, imam of Bordeaux’s Grand Mosque, and a prominent theologian, advocates a progressive Islam. He calls for a Muslim theology of adaptation to be made available to the young so that they won’t be drawn to the ideologies of Islamist extremism put forward by fundamentalists. Oubrou calls for imams to be trained in a “preventive” Muslim theology that is “terrorist proof” and “resistant to being coopted by fundamentalists.”34

In 2015, the Austrian National Council, perhaps motivated by a similar goal, revised the nation’s 1912 law establishing Islam as one of Austria’s official religions. The new provisions focused on undermining the political pressure on Austrian Muslims from funding sources and imam training centers outside of Europe, primarily from less democratic Muslim nations.35 The law is aimed at “creating an Austrian Islam, funded only by Austria… [and] promotes a linguistic shift encouraging the use of German in Muslim worship, instead of Arabic, Turkish or Kurdish.”36 Controversy over the 2015 legislation centered on the requirement that “Muslim faith groups… display ‘a positive attitude towards the society and the State.’”37

This provision may be a response to the fact that “Austria scored highest among 16 western European countries on an index of antipathy toward migrants” in 2011,38 and that Austrian scores had “considerably worsened” during the preceding decade.39 At the same time, ECRI reports that according to the annual surveys on attitudes toward integration conducted by Austrian authorities since 2010, “82 percent of migrants feel totally or mostly at home in Austria” in 2013.40 This, even though “Roma, Jews, Muslims and asylum seekers also figure among the main targets of hate speech” in Austria according to a 2012 survey conducted by the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA).41

Austrian police statistics report bias crimes and indicate that the majority (65 percent) were right wing extremist in orientation in 2013 (up from 56 percent in 2012).42 Given the hostility toward Muslims reflected in the data, the 2015 law underscoring the rights of Muslims as members of an official religion in the state might deliver both the message that Muslims belong in Austria and the tools (in terms of funding from within Austria and the teaching and practice of Islam in Austria’s official language, German) to assure that Islam puts down roots in the European state. Both Islamist and right wing extremists might find a weaker response to their incendiary rhetoric where the “ordinary” practice of Islam as an accepted Austrian religion is observed by about 7 percent of the Austrian population.

Samuel notes that in secular Europe, “any Muslim practice is a form of Islamism. This prejudice gets reflected by many politicians, on the right as on the left… Prejudices circulate, and fear is the response.”43 The Freedom Party plan, described by The Washington Post as an effort to “begin ‘monitoring’ Muslim institutions such as mosques and schools”44 in the event of a Hofer election to president appealed to this sort of fear. To counter condemnation of the Nazi roots of the Freedom Party, Johann Gudenus, vice mayor of Vienna, proclaimed: “‘The new fascism in Europe is Islamism.’”45 In Vienna, the Burgtheater, used to stage anti-Semitic works during the 1940s, was the scene of an April, 2016 right wing protest of a performance of Die Schutzbefohlenen, a play against xenophobia, written in 2013 by Austrian Nobel laureate, Elfriede Jelinek.46 Karin Bergmann, Director of the Burgtheater, voiced her concern to The Washington Post about “further right wing pressure if the anti-refugee, anti-Muslim Freedom Party” ascended to the government: “One doesn’t want to imagine it because it evokes memories of the 1930s, when right wing parties stoked up fears and pushed minorities to the margins… It could be that certain fears, certain instincts, are stoked up again.”47

Liberal democracy faces a similar risk in the Netherlands considering Geert Wilders’ warnings that a “tsunami of Islamization” would drown Dutch culture. Data from Ipsos MORI’s Perils of Perception in 201648 suggest that a general lack of demographic awareness could smooth the way for Wilders’ message and for right wing parties in general. Dutch respondents to the five questions included in the Index of Ignorance are the most accurate of those in the 40-country ranking. But, as in other western democracies, people in the Netherlands have an inflated perception of the size of the Muslim population in their European state. The average estimate (19 percent) of the proportion of Muslims in the Dutch population given by Dutch respondents is 13 percent higher than the actual proportion (6 percent). Perceptions regarding the growth of the Muslim population in the Netherlands are also inaccurate. Experts’ 2020 estimate is 6.9 percent, but Dutch respondents guess 26 percent on average.49 Rather than educate the Dutch population regarding the facts of Muslims’ minority demographic status and cracking down on racist offenses against Muslims, Dutch authorities have focused their attention on parliamentary debates regarding banning face-covering garments.50

Citizenship in their European state may provide Muslims with some protection from experiences of discrimination relating to nationality, but not uniformly

No wonder, then, that Muslim voters, and other citizens of migrant background have branched out from the traditional center left party (PPV) to support the new political party DENK (billed as an organization by and for those of migrant background), as well as D66 (Democracy 1966, formed in opposition to pillarization), the pro-European party on the left seen as the most consistent protector of multiculturalism and immigration. D66 increased its clout in 2017 to 19 seats, from 10 in 2010. DENK, the new political party formed by two Turkish members of the Dutch House of Representatives “to combat xenophobia and racism in the Netherlands,” met the 1,000-member threshold in time for funding and representation in the 2017 election.51

DENK specifically targeted institutional racism and Islamophobia in Dutch society, and celebrity members (such as Sylvana Simons) critiqued the Dutch system as designed in the past to “serve the dominant white race” at the expense of Muslims, Turks and blacks in Dutch society.52 But the greater rise of D66 over DENK in the number of seats gained in Parliament may be an indicator of the Dutch worldview characteristic of many Muslims and others of migrant background who call the Netherlands their home. Dutch television host Sylvana Simons, who was born in Surinam, initiated her run for political office as a member of DENK. Soon after, she switched to D66 partly because she wanted to support gay rights, an area of civil rights in which the Netherlands is quite strong and DENK is less inclined to support.

Discrimination against Muslims

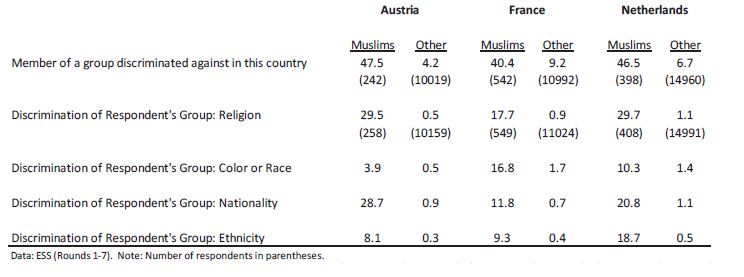

The EU Minorities and Discrimination Survey initiated by the Fundamental Rights Agency (which reports to the European Parliament), the European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (an independent agency of the Council of Europe), as well as data from the Eurobarometer and the European Social Survey, document discrimination toward Muslims in European states based on their religion, race and nationality. Some of these data up to 2008 were detailed for France and the Netherlands (as well as Germany and the United Kingdom) in Jackson and Doerschler (2012).53 In this paper we present more recent cumulative data from the European Social Survey (2002-2014 from European Social Survey Rounds 1-7) for Austria, France and the Netherlands below in Table 4. (Descriptions of the variables are in Appendix A.) The analysis suggests national differences in the basis of the discrimination recognized by Muslims in each state, highlighting the problems of intersectionality and multiple discrimination in bias against the religious minority.

Table 4: Percentage of Muslims Identifying as a Discriminated Group

Regarding intersectionality, sources of bias combine to exacerbate the discrimination or perceived distance between majority group members and those they perceive to be a minority. Multiple discrimination gives rise to intersectionality, in that more than one aspect of a person’s identity is singled out for bias. These problems manifest somewhat differently in the three countries we examine. In Austria, where Muslims represent about 6.9 percent of the population,54 close to 29 percent of them feel that the basis of discrimination against them is their nationality. About the same percentage of Muslims point to their religion as the source of discrimination against them, while smaller percentages feel that it is triggered by their ethnicity (8 percent) or race (4 percent). Close to 17 percent of French Muslims see race as the source of bias against them, just under the proportion who cite religion, while about 12 percent feel that their nationality is the target. French Muslims, then, are 17 percent less likely than their Austrian counterparts to feel that the bias against them is directed at their nationality, 13 percent more likely to see racial bias in the discrimination they face, and 12 percent less likely to cite religion. Overall, 40 percent of French Muslims indicate that they are discriminated against in their European state, 7 percent fewer than in Austria. The level and sources of discrimination recognized by Muslims in the Netherlands paint a unique picture, with some similarities to the situation of Muslims in Austria and France. 47 percent of Dutch Muslims report being a member of a group that is discriminated against, close to the figure in Austria, and 7 percent greater than in France. As is the case for Austrian and French Muslims, religion is the main source of bias reported by Dutch Muslims (close to 30 percent list it as a trigger of discrimination against them), followed by nationality (cited by 21 percent of Dutch Muslims as a source of bias against them). About 19 percent of Dutch Muslims cite their ethnicity as a target of discrimination, and 10 percent their race.

Citizenship in their European state may provide Muslims with some protection from experiences of discrimination relating to nationality, but not uniformly. European Social Survey Data summarized in Appendix B reflect the level of citizenship among Muslim respondents (selected as part of a representative sample of each European state) and indicate that about 59 percent of Muslim respondents in Austria hold its citizenship, while the figures are 73 percent for France and 86 percent for the Netherlands. As Table 4 indicates, French Muslim respondents are least likely to report feeling discriminated against based on their nationality, a difference that may to some extent result from their relatively high level of citizenship. But the pattern is not consistent, given that 86 percent of Dutch Muslim respondents are citizens of the Netherlands and still report a higher level of discrimination based on nationality than do French Muslims. Dutch Muslims are 9 percent more likely to report nationality-based discrimination than are French Muslims, and 8 percent less likely than are Austrian Muslims.

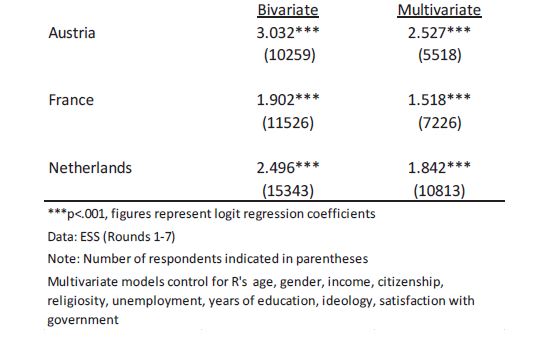

Table 5: Effects of Muslim ID on Reported Membership in a Discriminated Group

Multiple discrimination and intersectionality are characteristic of the bias expressed against Muslims in all three of these European states, even while the triggers for bias differentially reflect each state’s colonial or guest-worker history and related sources of minority/majority friction. Table 5 indicates that the link between Muslim religious identification and reported membership in a group that is discriminated against is statistically significant, even in multivariate equations controlling for background characteristics (including the respondent’s age, gender, income, citizenship, religiosity, unemployment, education, ideology and satisfaction with the government).

Hind Ahmas leaves the court after becoming the first women to be convicted with a fine of 120 Euros for wearing a niqab, after France’s nationwide ban on the wearing of face veils, on September 22, 2011 in Meaux, France. ABDULLAH AŞIRAN / AA Photo

Hind Ahmas leaves the court after becoming the first women to be convicted with a fine of 120 Euros for wearing a niqab, after France’s nationwide ban on the wearing of face veils, on September 22, 2011 in Meaux, France. ABDULLAH AŞIRAN / AA Photo

Discrimination is especially important when it impacts young adults, blocking their access to legitimate opportunities. Even as early as 2008, analysis of data from the European Social Survey for France and the Netherlands indicated that about half of Muslims aged 15-29 claimed membership in a group that was discriminated against. Other Muslims were over 10 percent less likely than their younger counterparts to report being in a group that is discriminated against.55

The 2016 report on France by the European Commission on Racism and Intolerance states that in political discourse “Muslims are… regularly stigmatized.”56 The report also cites a decline since 2009 (despite an uptick after 2012) in the tolerance of diversity as measured by the longitudinal index created by the Commission Nationale des Droits de l’Homme (CNCDH) in 2008 to measure changes in “French attitudes to diversity since 1990… in consolidated form.”57 The CNCDH analysis indicates that reported anti-Muslim acts more than tripled in 2015 (to 429) from 2014 (when 133 were reported).58

During the United Nations World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (2001) in Durban, South Africa, France and other signatory states agreed to a platform strongly urging states to implement national policies to combat racism, discrimination, xenophobia, and gender bias. The French National Action Plan against Racism and Intolerance was implemented in 2015.59 The program put forward 40 initiatives organized under four categories: mobilizing against racism and anti-Semitism; sanctioning every racist or anti-Semitic act and defending the victims; protecting internet users from the propagation of hatred; and educating citizens through school, culture and passing on values. Combatting racism and anti-Semitism was declared a “Major National Cause for 2015” by then French President Hollande in his New Year’s address. Titled “Mobilizing France against Racism and Anti-Semitism: 2015-2017 Action Plan,” the report describes the elements of the program and stresses their importance to France. Each act of racism, the plan begins, “weakens the Republic, especially if it goes unpunished. And racist abuse has taken place. This abuse is not only a threat to those who fall victim to it, French citizens who are Jewish or Muslim…” 60

Despite their experiences of discrimination, Muslims in Europe show no sign of having given up on democratic institutions

A civic sponsorship scheme through which young people will be offered the chance to be mentored for two years by a Citizen Reserves adult volunteer is part of the plan. “The aim is to enable young people to take full ownership of the values of the Republic, become involved in community life… undertake personal projects… and register on the electoral roll.”61 This effort to combat racism and anti-Semitism in France requires new policy development by several ministerial delegations of the state: education, justice, interior, culture, digital information, urban management, as well as the Inter-Ministry Delegate to the Fight Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (DILCRA, Delegation Interministerielle a la Lutte Contre le Racisme, l’Antisemitisme et La Haine Anti-LGBT). Overall, the initiative signals recognition that the French state can do more to prevent the exclusion of Muslims from civic and cultural life and that related steps can be taken to reduce anti-Semitism.

Similar concerns are at the forefront of anti-racist study group efforts in Austria. The 2015 ZARA (Zivilcourage und Anti-Rasissmus-Arbeit) report documents “a dramatic rise in the number of reported racist incidents in Austria, with a total of 927 incidents… an increase of 133…” over the preceding year.62 Refugees and asylum seekers increasingly were targeted by online posts including “glorification of Nazi violence, as well as false reports about criminal offenses committed by asylum seekers and the level of government spending on benefits for refugees.”63 These 927 registered incidents are distributed over the following nine areas of social, economic and cultural life: racism in public spaces (22 percent), over the internet (20 percent), in politics and the media (13 percent), graffiti (8 percent), by the police (6 percent), by other officials, public institutions and the service industry (5 percent), employers and businesses (4 percent), goods and services (15 percent), and in reaction to anti-racist work (7 percent).

Have European Muslims Lost Faith in Democratic Institutions?

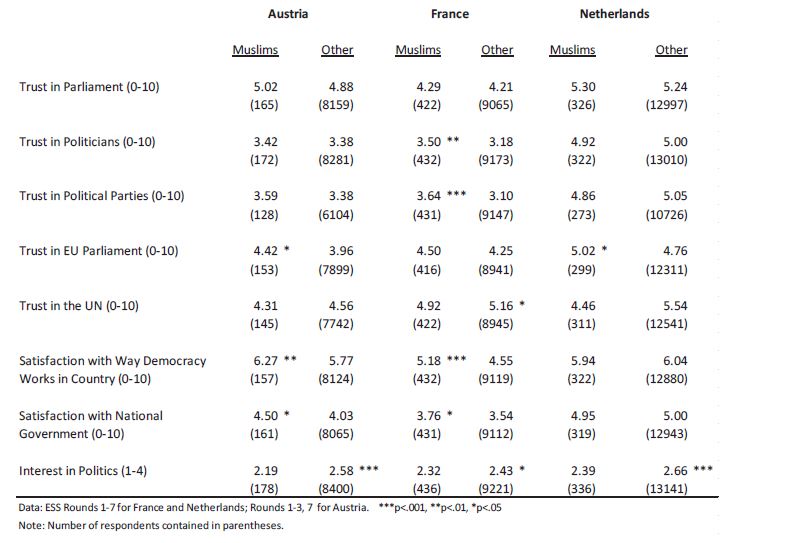

Despite their experiences of discrimination, Muslims in Europe show no sign of having given up on democratic institutions. Table 6, for example, indicates no significant difference between Muslims and non-Muslims in France and the Netherlands in terms of their trust in Parliament in cumulative data from the European Social Survey for the period 2002-2014. (Only the most recent round of ESS data is available for Austria, which similarly shows no significant difference between Muslims and non-Muslims in their trust in Parliament.) In addition, French and Austrian Muslims have greater satisfaction with democracy as it is practiced in their European country than their non-Muslim neighbors. And Dutch Muslims do not differ significantly from their non-Muslim neighbors in their satisfaction with democracy as it is practiced in the Netherlands.

Table 6: Comparing Mean Levels of Trust, Satisfaction and Interest in Government

Looking further at Austria, we find in the difference of means test results in Table 6 no significant difference between Muslims and non-Muslims on several trust in government measures. Muslims can’t be distinguished from their non-Muslim neighbors on their trust in the national parliament, politicians or political parties. These findings contradict the view that Muslims are at odds with the governing institutions and practices of their European state. Further support for the picture of Muslims as Europeans comes from the findings on satisfaction with the way democracy works in the country, and satisfaction with the national government. In both cases, those who self-identify as Muslims are more satisfied than non-Muslim Austrians. These findings suggest that Muslims in Austria feel represented by the national government despite right wing party demands that have threatened to steer official policies toward greater restrictiveness and weakened protections for the religious minority. Muslims may be satisfied that the center has held during what outsiders see as a political maelstrom fostered by far right supporters. Muslims in Austria are also less interested in politics than are others in Austria, as evidenced by the significantly higher mean level of interest for non-Muslims. Does this mean that while their neighbors grapple with questions of government direction, Muslims in Austria go about their daily lives, working, caring for their families, pursuing an education, supportive of the political process in their European state even while the outcomes are sometimes not to their advantage? Finally, trust in the EU Parliament is significantly greater for Muslims than for non-Muslims, which further supports the image of Muslims as Europeans who rely on national and supranational democratic governance to order their social and political life.

Muslims in Europe feel at home with the democratic institutions and processes of their member-state, despite the hostility expressed toward them by right wing parties and the mobilization of these parties for political change that would negatively affect the religious minority

The European Social Survey data on France, similarly, show few differences between Muslims and non-Muslims in terms of their trust in the governing institutions of their European state. Where there are differences, Muslims have more trust or are more satisfied than their non-Muslim neighbors. Specifically, Muslims have greater trust in politicians and political parties, and greater satisfaction with the way democracy works in France and with the national government. These results do not support the image of Muslims portrayed by French right wing parties, as isolated or alienated from European political institutions. Like the results for Austria, these data might be explained by experiences associated with Muslims’ immigrant family backgrounds in areas of the world with less political stability and by their relative upward mobility in contrast to their previous circumstances. The greater support for national political institutions displayed by French Muslims in contrast to their non-Muslim neighbors is particularly surprising considering the explicit and highly publicized criticism leveled at Muslims by the National Front during the last decade.

In the Netherlands, Table 6 provides a picture of great similarity between Muslims and non-Muslims in terms of their trust and satisfaction with the national government, the parliament and political parties. Muslims have slightly higher levels of trust in the EU Parliament. Like Muslims in Austria and France, Muslims in the Netherlands show significantly less interest in politics than their non-Muslim neighbors. The data for these three states suggest that Muslims in Europe feel at home with the democratic institutions and processes of their member-state, despite the hostility expressed toward them by right wing parties and the mobilization of these parties for political change that would negatively affect the religious minority.

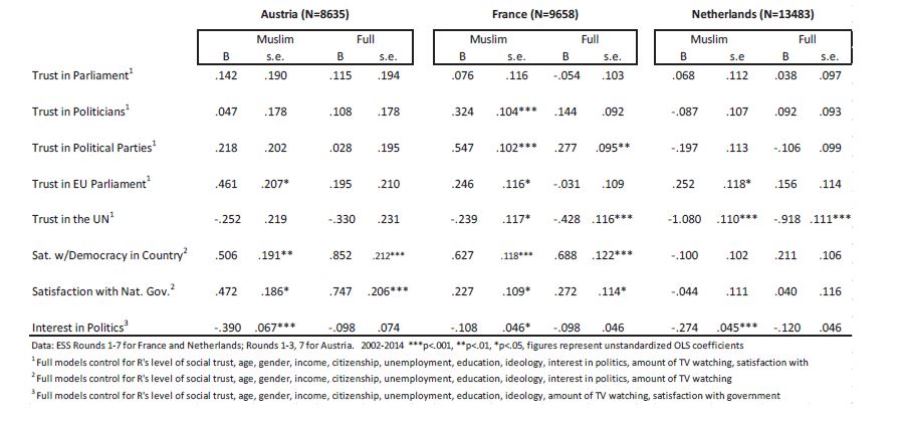

Table 7: Effects of Muslim ID on Trust, Satisfaction, Interest in Political Institutions and Values

In Table 7 with cumulative data for 2002-2014 we see that in multivariate equations Muslims in Austria remain more satisfied with democracy as it is practiced in their European state and with the national government, even with statistical controls for background characteristics (including social trust, age, gender, income, citizenship, unemployment, education, ideology, interest in politics and amount of television watching). Similarly, French Muslims have greater trust in the political parties than their non-Muslim neighbors, are more satisfied with democracy as it is practiced in France and with the national government in the multivariate results. Table 7 also indicates that Muslims in the Netherlands are not significantly different from their non-Muslim neighbors in areas relating to satisfaction with democracy or the national government, though, like French Muslims, they have significantly less trust in the United Nations once personal background characteristics are controlled.

People placed flowers in front of the Turkish Mosque successfully preventing PEGIDA members’ plans for a pork barbecue event near the mosque in Rotterdam, Netherlands on June 07, 2018. ABDULLAH AŞIRAN / AA Photo

People placed flowers in front of the Turkish Mosque successfully preventing PEGIDA members’ plans for a pork barbecue event near the mosque in Rotterdam, Netherlands on June 07, 2018. ABDULLAH AŞIRAN / AA Photo

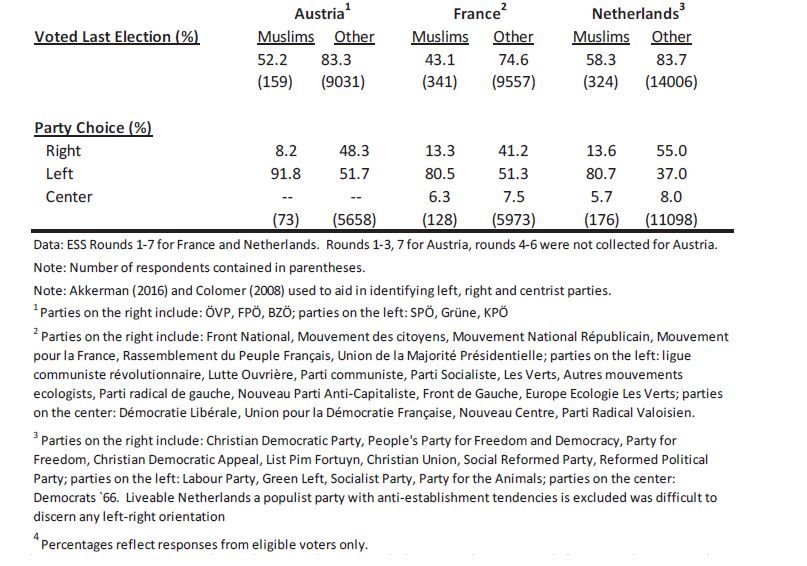

These results paint a picture at odds with the widely accepted image of Muslims as alienated from democratic institutions in European states. Rather, our comparison of Muslims’ political attitudes in Austria, France and the Netherlands yields a picture of Muslims as Europeans, differing from their non-Muslim neighbors in their European state primarily in terms of the religious minority’s greater support for democracy in the state and with the national government. In the current period of declining support for democracy in the west, Muslims in these three European states provide a contrast with their enthusiasm for democratic institutions. Muslims have a slack political resource in voting which could be utilized if their interest in politics were piqued. Table 8, with cumulative data from the European Social Survey from 2002-2014, demonstrates, for example, that Austrian Muslims were 30 percent less likely to vote in the last election than were non-Muslim Austrians. Why only 52 percent of Muslims in Austria voted is a question that deserves examination since they have greater satisfaction with democracy and with the national government than their non-Muslim neighbors. Are Austrian Muslims complacent, comfortable in a stable democratic state with individual rights and protections? Are they too busy to focus on politics and vote? Or do they feel that none of the political parties are worth their involvement or would welcome it? In any case, this question looms as an opportunity for Austrian political parties to capture a new interest group that is small, but favorably disposed toward the democratic institutions of the Austrian state.

Table 8: Comparing Electoral Participation, Vote Choice of Muslims and Non-Muslims

Similar findings characterize France and the Netherlands. Only 43 percent of French Muslims voted in the last election according to the ESS data ending in 2014 (beginning in 2002). As in Austria, Muslims in France were about 30 percent less likely to vote than their non-Muslims neighbors. In the Netherlands, the gap is 26 percent, with 58 percent of Muslims voting in contrast to 84 percent of non-Muslim Dutch. (Only Muslims eligible to vote are asked whether they have voted.) It is clear, then, that a path is open for greater Muslim influence over politics in these three European states. Over 80 percent of French and Dutch Muslims who reported participating in the last national election cast their vote for a party on the left (parties are listed in Table 8). In Austria about 92 percent of Muslims voted for a party on the left.

Though they represent a demographic minority (7-9 percent of the population) in each of these states, Muslims as a mobilized political bloc could more effectively work through the political parties to advocate for greater protections from discrimination and bias. They would represent an important counterweight to right wing voters in their European state. It is costly for a political party to openly insult a reliable and active group of voters, regardless of the party’s xenophobic priorities. The French “National Action Plan to Fight Against Racism and Anti-Semitism,”64 with its focus on registering the young from poor neighborhoods to vote, will, if successful, help to close the voting gap between Muslims and non-Muslims in France and could provide a model for other European states or political parties to invite greater participation by Muslims in electoral decision making at the state level.

Conclusions

The electoral support for far right parties in Austria, France and the Netherlands has come at the cost of the majority support for diversity that is a foundation of liberal democracy. In voting for the right wing party, close to half of the Austrian electorate, over a third of the French electorate, and 13 percent of Dutch voters acquiesced to overt expressions of hostility toward Muslims and others with a migrant background. With animosity toward them legitimated in hate speech promoted by right wing political candidates including Hofer, Le Pen and Wilders, Muslims in these three states face special scrutiny by their neighbors to whom they have become a visible religious minority. Yet despite the gain in seats and votes attained by far right parties, increasing public support for anti-immigration policies and limited state multicultural policy implementation, Muslims do not seem to have lost faith in the political or justice systems of Europe. Even while some of their non-Muslim neighbors feel discriminated against by existing national and European policies promoting and protecting diversity, and worry about their safety in the presence of a visible minority, Muslims are as likely as non-Muslims to trust the legal system and national parliament. They also appear to be no less satisfied than their non-Muslim neighbors with the way democracy works in their European country, and equally likely to trust in the EU Parliament.

With animosity toward them legitimated in hate speech promoted by right wing political candidates including Hofer, Le Pen and Wilders, Muslims in these three states face special scrutiny by their neighbors to whom they have become a visible religious minority

In the aftermath of the 2016-2017 elections in Austria, France and the Netherlands, Muslims face the challenge of a hardened electorate that points to terrorist incidents in Europe as rationale for hostility toward diversity. At the same time, the data for France collected (using quotas developed based on INSEE census data) by the Institut Montaigne65 suggest another challenge for Muslim parents seeking to guide their children toward democratic traditions. The fact that 28 percent of French Muslims have adopted values in opposition to the state gives cause for concern throughout Europe. While examination of recent data from the European Social Survey (up to 2014) does not show Muslims’ disaffection from state democratic institutions, it is likely that Muslim children have friends in school who are among the “rebellious 28 percent.” The efforts by French mosques to offer religious training that is resistant to cooptation by fundamentalists will be important to parents seeking to prevent their children’s distancing from Europe. Tolerance-building activities of the state, such as the Austrian law legitimizing Islam, and the French National Action Plan against Racism and Anti-Semitism, will also be key, along with inclusive political parties such as DENK and D66 in the Netherlands. Muslims deserve this support from the state, political parties, and mosques, in emphasizing the religious minority’s European identity in nations where up to half of the electorate is hostile toward them.

Greater involvement in politics by voting is also warranted, even though Muslims represent fewer than 10 percent of the population in each of these nations. Voting, after all, fits with the pattern of trust in state governance institutions and satisfaction with democracy consistently reflected in the data on Muslims in Europe. Small but politically active voting blocs can influence public policy over time. By way of example, Muslims have only to look at the tilt toward right wing agendas since 1990 in their own European states. While the diversity of their immigrant background has prevented Muslims in Europe from thinking of themselves as a single diaspora, members of this religious minority share experiences of discrimination, and face both increasing hostility and growing concern for their children’s ability to prosper within the European Union. These conditions threaten Muslims’ claims to full participation in Europe and provide sufficient rationale for their sustained political mobilization toward policies accommodating their religious and cultural backgrounds.66 Voting represents an essential part of that mobilization and would provide a platform from which to open a place for Muslims’ greater inclusion in the national culture.

Appendix A: Variable Labels and Coding

Variable Question Coding

RLGDNM Muslim 1,0, 1=muslim

DSCRGRP Member of discriminated group in this country 1,0 1=yes

On What Grounds is Your Group Discriminated Against:

DSCRRLG Religion 1,0 1=yes

DSCRRCE Color or Race 1,0 1=yes

DSCRNTN Nationality 1,0 1=yes

DSCRETN Ethnic Group 1,0 1=yes

AESFDRK Feeling of safety of walking alone in local area after dark 1-4, 4=very safe

VOTE Voted last national election 1,0 1=voted

PRTVT Party voted for in last general election

TRSTUN Trust in the United Nations 0-10, 10=complete trust

TRSTEP Trust in the European Parliament

TRSTPLT Trust in national politicians

TRSTPRL Trust in country's parliament

TRSTPRT Trust in political parties

STFDEM How satisfied with the way democracy works in country 0-10, 10=extremely satisfied

STFGO How satisfied with the national government

POLINTR How interested in politics 1-4, 4=very interested

UEMPLI1 Unemployed, wanting a job but not actively seeking 1,0,1=unemployed

UEMPLA1 Unemployed and actively looking for a job 1,0,1=unemployed

HINCTNTA Household's total net income, all sources 1-10 (first decile to tenth decile)

AGEA Age of respondent 16-101

GNDR Gender 1,0 1=female

EDUYRS Years of full-time education completed 0-48

LRSCALE Placement on left-right scale 0-10, 10=farthest right

RLGDGR How religious are you 0-10, 10=very religious

CTZCNTR Citizen of Country 1,0 1=yes

Data: ESS, rounds 1-7 for France, Netherlands; rounds 1-3, 7 for Austria

- Variables were combined into a single measure of unemployment

Appendix B. Percent Muslim Who are Citizens of Each Country (%)

Austria 59.0

France 73.4

Netherlands 86.0

Data: ESS (Rounds 1-7)

Endnotes

- Information and data for this study were obtained from the European Commission on Racism and Intolerance, the Fundamental Rights Agency, Statistics Netherlands, INSEE, the European Social Survey, http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/, the Pew Research Center, Chapel Hill Expert Survey http://chesdata.eu/, the Multiculturalism Policy Index http://www.queensu.ca/mcp/home, the Parliaments and Governments Database, www.parlgov.org, and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, http://www.start.umd.edu/. We thank these organizations for access to the data and take responsibility for the conclusions and opinions presented in this paper.

- See, Pamela Irving Jackson and Peter Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe: Reducing Disparities and Polarizations, (University of Bristol, UK: The Policy Press, 2012); Jan Niessen and Thomas Huddleston, “Setting Up a System of Benchmarking to Measure the Success of Integration Policies in Europe,” European Parliament, Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs, (Brussels, 2007), p. 71.

- “Proposed Indicators for Measuring Integration of Immigrants and Minorities with a View to Equal Rights and Opportunities for All,” Council of Europe, (MG-IN Strasbourg, 2003), p. 7.

- See, Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe, p. 1.

- Loretta Bass, African Immigrant Families in another France, (UK: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015).

- See, Stephanie L. Mudge, “Explaining Political Tunnel Vision: Politics and Economics in Crisis-Ridden Europe, Then and Now,” European Journal of Sociology, Vol. 56, No. 1 (2015), pp. 63-91.

- Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe.

- See, Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe, pp. 69-70; “Report on the Prevention of Racism, Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia,” Commission Nationale Consultative des Droits de l’Homme (CHCDH), (Paris, 2016), retrieved from http://www.cncdh.fr/sites/default/files/les_essentiels_-_report_racism_2015_anglais.pdf, p. 19.

- See, Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe, p. 69.

- See, Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe, p. 118.

- See, Bass, African Immigrant Families in Another France.

- Anthony Faiola, “Austria’s Right-Wing Populism Reflects Anti-Muslim Platform of Donald Trump,” The Washington Post, (May 19, 2016), retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/

austrias-right-wing-populism-reflects-anti-migrant-anti-muslim-platform-of-donald-trump/2016/

05/19/73368bbe-1c26-11e6-82c2-a7dcb313287d_story.html?utm_term=.8c3a049d2eae. - “Across the Continent, Rightwing Populist Parties Have Seized Control of the Political Conversation. How Have They Done It? By Stealing the Language, Causes and Voters of the Traditional Left,” The Guardian, (November 1, 2016), retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/01/the-ruthlessly-effective-rebranding-of-europes-new-far-right?CMP=share_btn_link.

- Kim Hjelmgaard, “Would-be Dutch PM: Islam Threatens Our Way of Life,” USA TODAY, (February

21, 2017), retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/02/21/exclusive-usa-

today-interview-with-dutch-anti-islam-politician-geert-wilders/98146112/. - “The Perils of Perception in 2016,” Ipsos MORI, p. 4, retrieved from http://perils.ipsos.com/slides/.

- Peter Doerschler and Pamela Irving Jackson, “Radical Right-Wing Parties in Western Europe and their Populist Appeal: An Empirical Explanation,” Forthcoming in Societies without Borders, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2018).

- For further discussion of state and party selection, see Doerschler and Jackson, “Radical Right-Wing Parties in Western Europe and their Populist Appeal”; Tijitske Akkerman, Sarah L. de Lange and Matthijs Rooduijn (eds.), Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream?, (New York: Routledge, 2016), p. 2.

- As reported in Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn (eds.), Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe, p. 2; see also 2016 Parliaments and Government Database, retrieved from http://www.parlgov.org/.

- See, Tim Bale, Christoffer Green-Pedersen, Andre Krouwel, Kurt Richard Luther and Nick Sitter, “If You Can’t Beat Them, Join Them? Explaining Social Democratic Responses to the Challenge from the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe” Political Studies, Vol. 58, No. 3 (2010), pp. 410-426. See also Cas Mudde, “The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy,” Eurozine, (August 31, 2010), retrieved from http://www.eurozine.com/the-populist-radical-right-a-pathological-normalcy/; Doerschler and Jackson, “Radical Right-Wing Parties in Western Europe and their Populist Appeal.”

- Griff Witte and Luisa Beck, “For Austria’s Muslims, Country’s Hard-Right Turn is an Ominous Sign,” The Washington Post, (October 20, 2017), retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/for-austrias-muslims-countrys-hard-right-turn-signals-an-ominous-direction/2017/10/19/c3389c8c-b357-11e7-9b93-b97043e57a22_story.html?utm_term=.1882f4dcf5c7.

- Melissa Eddy, “Swift Rise in Austria for Populist Leader,” The New York Times, (October 16, 2017), retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/16/world/europe/sebastian-kurz-austria.html?_r=0.

- See reference to the analysis of political scientist Ivan Krastev in Steven Erlanger and James Kanter, “Austria’s Rightward Lurch Reflects Europe’s New Anti-Immigration Leanings,” The New York Times, (October 16, 2017), retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/16/world/europe/austria-election-right.html.

- Tim Boersma, “The Netherlands’ Complicated Election Result Explained,” Brookings, (March 20, 2017),

retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2017/03/20/the-netherlands-

complicated-election-result-explained/. - Boersma, “The Netherlands’ Complicated Election Result Explained.”

- Keith Banting and Will Kymlicka, “Is There Really a Retreat from Multiculturalism Policies? New Evidence from the Multiculturalism Policy Index,” Comparative European Politics, Vol. 11, No. 5 (2013), pp. 577-598. See also, Multiculturalism Policy Index, retrieved from http://www.queensu.ca/mcp/.

- Elisabeth Ivarsflaten, “What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe?” Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1 (2008), pp. 3-23.

- See, Daniel Oesch, “Explaining Workers’ Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland,” International Political Science Review, Vol. 29, No. 3 (2008), pp. 349-373.

- See, START website at the University of Maryland, http://www.start.umd.edu/.

- See, Rahsaan Maxwell and Erik Bleich, “What Makes Muslims Feel French?” Social Forces, Vol. 93, No. 1 (2014), pp. 155-179; Justin Gest, Alienated and Engaged: Muslims in the West, (New York: Columbia University, 2010).

- Hakim el Karoui, “A French Islam Is Possible,” Institut Montaigne, (September, 2016), retrieved from http://www.institutmontaigne.org/res/files/publications/a-french-islam-is-possible-report.pdf.

- El Karoui, “A French Islam is Possible,” pp. 7-8.

- El Karoui, “A French Islam is Possible,” p. 18.

- El Karoui, “A French Islam is Possible.”

- Sigal Samuel, “Should France Have Its Own Version of Islam?” The Atlantic, (April 25, 2017), retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/04/muslims-france-election/524178/.

- See, “Austria Passes Controversial Reforms to 1912 Islam Law,” BBC, (February 25, 2015), retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-31629543.

- El Karoui, “A French Islam is Possible,” p. 67.

- El Karoui, “A French Islam is Possible.”

- “European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) Report on Austria,” Council of Europe, (Strasbourg, 2015), p. 26.

- “Intolerance (ECRI) Report on Austria,” Council of Europe, p. 18.

- “ECRI Report on Austria.”

- “ECRI Report on Austria,” p. 18.

- “ECRI Report on Austria,” p. 17

- Sigal Samuel, “Should France Have Its Own Version of Islam?” p. 4.

- Anthony Faiola, “Austria’s Right-Wing Populism Reflects Anti-Muslim Platform of Donald Trump,” The Washington Post, (May 19, 2016), p. 3.

- Faiola, “Austria’s Right-Wing Populism Reflects Anti-Muslim Platform of Donald Trump.”

- “Austrian Extremists Scale Theatre Roof in Latest Protest,” The Local, (April 28, 2016), retrieved from https://www.thelocal.at/20160428/extremists-scale-roof-of-austrian-theatre-in-latest-protest.

- Faiola, “Austria’s Right-Wing Populism Reflects Anti-Muslim Platform of Donald Trump,” p. 4.

- “The Perils of Perception in 2016,” p. 4.

- “The Perils of Perception in 2016,” p. 6.

- See, “European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) Report on the Netherlands,” Council of Europe, (Strasbourg, 2013), p. 43.

- Nina Siegal, “A Pro-Immigrant Party Rises in the Netherlands,” The New York Times, (July 29, 2016), retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/30/world/europe/dutch-denk-party.html.

- Lauren Frayer, “With the Far-Right Rising, Dutch Create Their Own Parties for Immigrants,” National

Public Library, (January 10, 2017), retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/01/10/

507243028/with-the-far-right-rising-dutch-create-their-own-parties-for-immigrants. - See, Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe, p. 105-120.

- Conrad Hackett, “5 Facts about the Muslim Population in Europe,” Pew Research Center,

(November 27, 2017), retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/29/5-facts-

about-the-muslim-population-in-europe/. - See, Jackson and Doerschler, Benchmarking Muslim Well-Being in Europe, p. 118.

- “European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) Report on France,” Council of Europe, (Strasbourg, 2016; Adopted 2015), p. 15.

- “ECRI Report on France,” p. 15.

- “Report on the Prevention of Racism, Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia,” p. 11.

- “Mobilizing France against Racism and Anti-Semitism: 2015-2017 Action Plan,” Delegation Interministerielle, (2015), retrieved from http://www.gouvernement.fr/sites/default/files/contenu/piece-jointe/2015/05/dilcra_mobilizing_france_against_racism_and_antisemitism.pdf.

- “Mobilizing France against Racism and Anti-Semitism: 2015-2017 Action Plan, p. 1.

- “Mobilizing France against Racism and Anti-Semitism: 2015-2017 Action Plan, p. 12.

- “ZARA Racism Report 2015,” ZARA (Zivilcourage und Anti-Rasissmus-Arbeit), (2016), retrieved from https://www.zara.or.at/_wp/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/Zara_RR15_English_RZ_kl.pdf.

- “ZARA Releases Report on Racism in Austria,” United against Racism, (March 24, 2016), retrieved from http://www.unitedagainstracism.org/blog/2016/03/24/zara-releases-report-on-racism-in-austria/.

- “Mobilizing France against Racism and Anti-Semitism: 2015-2017 Action Plan.”

- El Karoui, “A French Islam is Possible,” p. 12.

- See, Maria Koinova, “Sustained vs. Episodic Mobilization among Conflict-Generated Diasporas,” International Political Science Review, Vol. 37, No. 4 (2015), pp. 500-516