Introduction

Historically, social movements and local protests have often arisen from those of middle- or working-class backgrounds who have demonstrated the courage and skill to organize others at great personal sacrifice and peril.1 These reformist movements and organizations, spearheaded by a new middle class, have embraced the rhetoric and instruments of social justice and human rights –both domestically and from an international standpoint– not just as empowering tools but also as vehicles for building social solidarity across the globe. The spread of the middle class across the world has been equated with evolving norms and values. In recent years, however, democratic systems of governance appear to have been in a state of atrophy. Iran’s middle classes have felt threatened by the lingering economic hardship caused by the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, negative consequences of global free trade, and the ongoing U.S. sanctions. This trend has generated contradictory results, making some members of the middle classes more motivated to participate in the political process to rectify wrongs, and others resigned to a pessimistic view with little or no desire to challenge or even hold the government accountable.

Iran’s once vibrant and thriving reformist movement closely associated with the middle class, which has always been known for demanding a democratic remedy, has hit a dead end. With all the levers of power now in control of conservative forces, many members of the middle class appear skeptical about their current and future role in promoting democratic values. Having entered a corridor of uncertainty and economic insecurity, they appear more and more discouraged about the availability of a democratic alternative. This can be explained in part by the way in which the Islamic Republic has utterly failed to cultivate meaningful links with some members of the middle class, leading to challenging times of unprecedented government mistrust.

Equally detrimental have been renewed U.S. economic sanctions on oil exports and other sectors of the economy that followed President Trump’s decision to leave the nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). These sanctions led to the severe devaluation of the Iranian currency, skyrocketing inflation, and the shrinking of the middle class, leaving basic commodities inaccessible to ordinary Iranians.2 These crushing sanctions, by contrast, have empowered the revolutionary guards whose advocacy of the so-called “resistance economy” has prevailed.3

To better fathom the growing sense of disillusionment with participation in a political process that is increasingly bereft of democratic legitimacy, we turn our attention to the mismanagement of the economy and endemic corruption, but more specifically, we examine the impacts of the harsh sanctions that have crippled Iran’s economy. Although all this has resulted in a great deal of economic insecurity for the vast majority of Iranians, this is not to say that there is no reason for optimism or hope. While the campaign for political reform has faded away, its message is particularly germane as the country’s middle class struggles to make ends meet.

In this essay, we attempt to unlock the socio-economic and political dynamics of this trajectory in a country whose middle class once thrived as the engine of social change and moderation. In the sections that follow, we examine the emergence of Iran’s middle class and its role in promoting democratic values in the aftermath of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Our focus then shifts to the impact of sanctions on the country’s GDP, the standard of living, the poverty rate, and the gradual erosion of the modern middle class. After demonstrating that the future of the middle class looks uncertain at best, we conclude that the persistence of authoritarianism, when combined with religious populism, will bear serious and long-term consequences for the country’s middle class. The reformist movement, which has relied heavily on the support of the middle class, appears increasingly lackadaisical and spiritless in the wake of the ongoing democratic rollback in Iran.

The reformist movement, which has relied heavily on the support of the middle class, appears increasingly lackadaisical and spiritless in the wake of the ongoing democratic rollback in Iran

The 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Middle Class

The modernizing programs and development projects initiated by the Pahlavi dynasty were supposed to produce an urban middle class supportive of the regime. The dynasty’s neo-patrimonial structure of power, however, never allowed the emergence of a new middle class capable of providing a solid base of support for the regime. On the contrary, the growth of middle class members expanded the ranks of the opposition. With the advent of the Islamic Republic, several factors combined to transform the country’s class structure. These included, among other things, the rise in education levels, the growth in urban population size, the expansion of bureaucracy, soaring income levels, and changing lifestyle and consumption patterns. Evolving lifestyles affected housing, how to spend leisure time, financial planning and saving, and the pursuit of modern domestic technology, including washing machines and color Television. The new middle class after the revolution was the product of several key factors, including, but not limited to, urban population, literacy rate, the state of higher education, the expansion of government bureaucracy, and lifestyle.

Urban Population

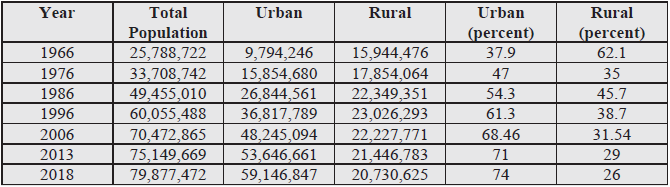

The growing urbanization since the 1979 Iranian Revolution has generated both attitudinal and behavioral changes characteristic of a new middle class. In Iran, according to the 1986 census, for the first time, the urbanization coefficient was, at 54.3 percent, higher than the ruralization coefficient. The urban population of the country in 1976 was approximately 16 million. By 2006, it had exceeded 48 million (68.46 percent).4

In the last census, conducted in 2016, Iran’s total population was 79,877,472, of which 59,146,847 lived in urban areas, and 20,730,625 resided in rural areas.5 According to this data, a section of the population is continuously commuting for work, from urban to rural areas and vice versa.6 In addition to urban attractions (greater prosperity, economic, educational, communication, and political resources), development plans such as communications have accelerated this process. The table below shows the growth of the urban population in relation to the rural population in the years following the Iranian Revolution. During the 1980s, as shown in Table 1, the country’s urban population trends began to show rapid growth.

Table 1. The Growth of Urbanization in the years following the Iranian Revolution

Source: Statistical Center of Iran7

Literacy Rate

The growth in the literacy rate, which began in the mid-Pahlavi period (1960s), continued at a much faster pace in the post-revolutionary period than before. The literacy rate increased from 27 percent in 1953 to 84.61 percent in 2006. By 2016, that rate had increased to 88 percent.8 These changes created a new middle class with different capabilities and expectations that staked new claims on the government. Acutely aware of state-society relations, this class showed a greater proclivity to participate in the political process and exercise greater influence on governance.9 The surge in the female literacy rate also provided significant social capital for the reformist movement that defied the archaic views about the subordinate role of women in politics. In Iran, approximately half the population is female and women make up a progressively larger share of its university graduates.10

The surge in the female literacy rate also provided significant social capital for the reformist movement that defied the archaic views about the subordinate role of women in politics

In 2017, according to Hossein Tavakkoli, an official with the Sanjesh Organization that is in charge of holding the university entrance exam, out of 378,706 participants who were admitted to the universities nationwide, some 213,884 (57 percent) were females, and 164,822 (43 percent) were males.11 The narrowing gender gap in education in Iran is well documented and has been studied from different dimensions.12 The literacy rate difference between men and women, according to Shapour Mohammadzadeh, head of the Literacy Movement Organization in Iran, has declined from 26 percent before the 1979 Revolution to 2.8 percent in August 2020.13 The literacy rate among Iranian women, Mohammadzadeh added, stood at 28 percent prior to 1979. By early 2020, nearly 90 percent of women could read and write.14

This increase in female literacy presents both great advantages and potential risks for the Islamic Republic. On the positive side, more and more educated females have entered the labor force, giving a significant boost to the country’s service sector, including banking and finance, hospitality, hotels, education, insurance, health, social work, computer services, communications, electricity, gas and water supply. This sector, however, has been one of the sectors hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in the loss of jobs for women.15

Notwithstanding these turbulent times and the global economic crisis, women have continued to fight against unjust laws and restrictions.16 Their movement in Iran has steadily grown into a skillful and inspiring feminist model for those seeking equal rights and gender justice.17 Islamist and secular women alike have begun to reject their confinement to the home and have managed to participate in the public sphere through their socio-economic activities. In doing so, they have contributed vigorously to the development of civil society access for women in Iran. Some Islamist women have even argued that “the ideals of the revolution cannot be attained unless women are present in the public sphere.”18

The State of Higher Education

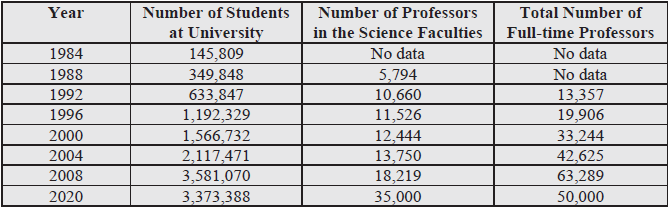

In the early days of the revolution, higher education stagnated due to the closure of universities, but with the reopening of universities and the establishment of two private and non-profit higher education centers (Islamic Azad University and Imam Sadegh University) in 1982, the number of student enrollments at colleges and universities dramatically increased. In 1997, the number of students at the Islamic Azad University increased to about 659,000 (a 7.8 percent increase). In 1999, the number of higher education students across Iran reached 1.5 million, as this trend continued unabated. Also, during these years, the number of faculty members increased from 5,794 in 1989 to 18,219 in 2008 and to 35,000 in 2020.19 Table 2 shows the total number of students and faculty members after the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Table 2. Numbers of University Students and Professors after the 1979 Iranian Revolution

Source: Statistical Center of Iran20

As this data illustrates, with the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the number of students and faculty members gradually increased. The number of students increased from 349,848 at the end of the first decade of the revolution to 3,581,070 by 2009. By 2019, some 85,000 full-time faculty members were working in state and private universities.21 The increase in the number of educated people meant rising demands for social change and mounting pressure on the government to initiate democratic change.22 The Islamic Republic’s agenda in this regard was both ambitious and, on its own, destabilizing. It was destabilizing in part because the reformist movement gained considerable strength, and by 2009, it flexed its newly gained power of protest in the so-called “Green Movement.” Although the Green Movement yielded no tangible results, it posed daunting challenges to the Islamic Republic, especially the way in which the regime came under stress. In short, the Islamic Republic arguably became the victim of its own success in promoting higher educational standards.

Expansion of Government Bureaucracy

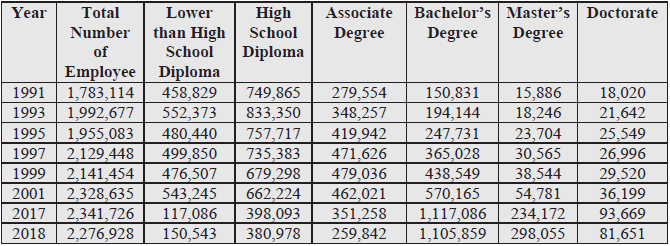

The growth and expansion of government and state bureaucracy was another feature of the growth of the new middle class. The number of government employees increased from 1,783,114, in 1991 to 2,328,635 in 2001. These figures do not include the number of salaried employees of the Ministry of Intelligence, the Ministry of Defense, Armed Forces Logistics, or companies under the government organizations; due to confidentiality, roughly an additional one million people, which, if added, would bring up the total salaried employees to approximately 3.5 million.23 In addition, the number of highly educated employees has increased. Table 3 shows the number of government employees from 1991 to 2001 based on level of education.

Table 3. Government Employee Level of Education from 1991 to 2001

Source: Statistics and Information of the Employees of the Executive Organs of Iran24

By 2018, these numbers had risen to: lower than high school diploma, 150,543; high school diploma, 380,978; associate degree, 259,842; bachelor’s degree, 1,105,859; master’s degree, 298,055; and doctorate, 8,651.25 As the table above shows, the number of employees with higher education has increased, allowing government employees a bigger say and larger role in the decision-making and the policy implementation.26

Lifestyle

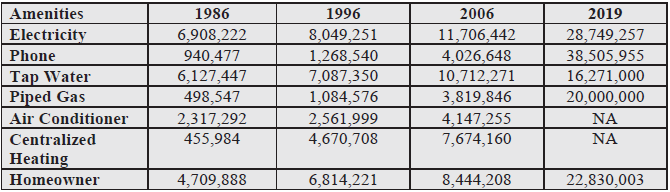

The number of households that owned a car increased from 18.3 percent in 1977 to 42.5 percent in 2019.27 In 1977, in rural areas, only 7.6 percent of households had a refrigerator, and 18.8 percent had a stove; in 1989, these ratios reached 49.3 percent and 56.2 percent, respectively. That is to say, the use of the refrigerators increased 6.5 times, and stoves tripled. In cities, the use of refrigerators increased from 73 percent of households to 90 percent, and stoves from 70 percent to 87 percent. While in 1977, approximately 3.2 percent in rural areas and 52 percent in urban areas had televisions, this rate in 1989 increased to 41 percent in rural areas and 87 percent in urban areas. By 1996, some 10,416,983 households owned a television. The extent to which households enjoy other such domestic amenities is shown in Table 4.28

Table 4. Household Amenities

Source: Statistical Center of Iran29

In short, in the aftermath of the revolution, a solid foundation was laid for the growth of the new middle class. The state education plan and policies, the expansion of private and semi-private universities, increasing literacy, sprawling urbanization, and lifestyle changes led to the emergence of a new class that had a higher level of awareness and elevated expectations of the political system. The eight-year term of Hashemi Rafsanjani’s presidency (1989-1997) proved to be a turning point in the formation and growth of this class. Yet this class carried within it two inherent opposing characteristics that were noticeably influenced by the religious culture of Iranian society: the new religious middle class and the new fairly secular middle class. Religious intellectuals –urbanites associated with religious institutions and part of the bureaucratic forces– were from the new religious middle class that had played a key role in the victory of the Iranian Revolution. After the revolution, the religious middle class gradually split into two groups: religious reformists and religious fundamentalists.

At the same time, there emerged a new relatively secular middle class that included part of the private sector economic activists and many others who were familiar with Western societies and new media. This group, which advocated secularism and pluralism in politics, gradually expanded its ranks in the second decade of post-revolutionary Iran, seeking to expand and strengthen its role in society.30

From Political Development to Economic Security

Prior to the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the ruling aristocracy, senators, ministers, and managers of the Pahlavi era were considered part of the upper classes. They nevertheless lost their perks, privileges, and powers immediately after the revolution. Between 1979 and 1989, however, the traditional Bazaari class (merchants and businessmen) was upgraded to the upper class in large part due to their active participation and formidable support for the revolution. During the presidency of Hashemi Rafsanjani, however, the traditional Bazaari bourgeoisie encountered a new competition from the industrial bourgeoisie (technocrats, industrialists, and investors), with the latter rising to the level of the upper class while also undercutting the position of the traditional forces of the Bazaar. Subsequently, a tacit coalition was forged among some members of the modern middle class and part of the lower class that paved the way for the landslide victory of President Seyyed Mohammad Khatami in 1997.31

Prior to the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the ruling aristocracy, senators, ministers, and managers of the Pahlavi era were considered part of the upper classes

Ebrahim Raisi supporters celebrating after the announcement of his victory, in the Iranian presidential election on June 19, 2021, in Tehran, Iran. MEGHDAD MADADI ATPImages / Getty Images

After Rafsanjani’s government came to power, the interests of the new middle class expanded due to the economic development and relative social mobilization that took place during this period. These interests were mostly in the political sphere and included participation in political affairs, freedom of expression, and the rule of law. Rafsanjani’s economic programs led to the expansion of higher education and hence the middle class. Yet, at the same time, the lack of political freedoms alienated the educated and intellectual classes. In the ensuing elections, Khatami came to power, promising an open political climate. The result was the emergence of a new middle class in ministries and several state institutions, including the parliament.

Between 1997 and 2005, the new middle class grew powerful, gaining more leverage than in the past in both the social and political realms. Increasingly, Iran’s new and urban middle class, from intellectuals to middle class parties and from journalists to technocrats, found its way into the corridors of power. During the Khamati era (1997-2005), despite the expansion of civil society and democratic openings, economic hardship intensified income inequality, caused further poverty, and spurred rampant inflation. Not surprisingly, in the 2005 presidential election, the lower classes of the society, with about 11 million votes in the first round of elections, appeared on the Iranian political scene, this time without aligning their interest with those of the middle class.32 While in the 1997 elections, the lower class and the new middle class forged an alliance to support Khatami, in the election of 2005, by contrast, the lower class broke its alliance with the middle class, and its political demands took a different turn. The revolutionary middle class became the conservative middle class in 2005.33

The formation of social classes after the election of 2009 was fundamentally altered, as the new middle class found themselves marginalized by the populist and pro-poor policies of the Mahmoud Ahmadinejad Administration. The common aspirations of this class led to their cohesion for the eleventh presidential election in 2013 and the tenth term of the Iran parliamentary elections in 2015. A great sense of pessimism and frustration gripped the new middle class. Yet they proved energetic enough to participate in the 2009 elections and its subsequent protest movement known as the “Green Movement,” challenging the second-term election of Ahmadinejad. In the ensuing presidential elections of 2013 and 2017, the participation of the new middle class proved crucial to the election of Hassan Rouhani.

While Rouhani’s success in signing the 2015 nuclear deal with the P5+1 was seen as a substantial foreign policy gain for his administration, the re-imposition of further sanctions by the Trump Administration resulted in significant economic hardship for the vast majority of Iranians, dramatically undermining Iran’s reformist camp. Iran’s June 2021 presidential election, which led to the victory of Ebrahim Raisi, also showed the frustration of the middle class. In this election, about 48.8 percent of eligible voters participated, which was the first time that less than half of all eligible voters participated in a presidential election. Of those who voted, approximately 12 percent cast ballots (white or distorted votes) in the ballot box as a sign of protest vote.

The participation rate in large cities, which mainly consists of the middle class, was even lower than 48.8 percent. Most notably, in Tehran, the participation rate was 26 percent. One of the reasons for this dramatically low turnout was the way in which the Guardian Council disqualified all major reformist candidates from the race. Only two candidates close to the reformists, who were less well known on the reformist spectrum, were vetted. This issue manifested itself more in the protest votes (11.86 percent) and the non-participation of the middle class in this election than anything else.

As a result, reformists have gradually lost their credibility with a large segment of their supporters. Even with the encouragement of major reformists like Mohammad Khatami, Mehdi Karroubi, and Behzad Nabavi, many reformist groups and factions refused to participate in the latest presidential election. This stood in stark contrast to how the former president, Mohammad Khatami, in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections motivated a massive wave of support for the election of a moderate candidate like Rouhani.

The assassination of Saeed Hajjarian, a reformist political strategist, the attack on the dormitory of the University of Tehran in 1999, and the arrest of members of the “Islamic Iran Participation Front,” who were among the main leaders of the reformist movement, further weakened this political movement after the 2009 presidential election. During Rouhani’s presidency, the reformist social base, despite the restrictions imposed during Ahmadinejad’s presidency, once again relied on the authority of the reformists to vote for Hassan Rouhani. After the 2015 nuclear deal, conservatives attacked the Saudi embassy in Iran to undermine Rouhani’s foreign policy, and provocative missile tests were carried out to complicate –if not weaken– Rouhani’s foreign policy stance.

During Rouhani’s presidency, the reformist social base, despite the restrictions imposed during Ahmadinejad’s presidency, once again relied on the authority of the reformists to vote for Hassan Rouhani

As noted above, in addition to the low level of public participation in the recent presidential election, which was a record low turnout in a presidential election after the 1979 revolution, the increase in the number of invalid votes in this period has been many times more than in the previous presidential elections. These invalid ballots were, in fact, a follow-up to the campaign that was formed before the election, signaling a sign of protest against the election. More than 3.7 million people who participated in the thirteenth presidential election refrained from writing the names of any candidates on their ballots, a remarkable sign of protest of this election. In addition, 51.2 percent of eligible voters did not vote, illustrative of a widespread boycott of the election.34

Although not all those who boycotted the presidential election were, in fact, opponents of Iran’s political system, many were distrustful of the current political regime. This was clearly a reaction to the way in which the Guardian Council restricted the number of presidential candidates. Many reformists considered this a prelude to the rollback of democracy in the coming years. Conservatives, however, blamed the Rouhani government for the low turnout, attributing the lack of the usual levels of participation to a backlash against the poor performance of the Rouhani Administration –and not to the political regime. The weakening of the modern middle class also had much to do with such a low turnout.

The Impact of Sanctions on Iran’s Social Classes

The concern with poverty has almost always been related to the lower levels of Iranian society. Today, however, poverty has also gripped those sections that are not normally seen as the poor. The prevailing perception inside and outside of these layers has been that they are less likely to become poor.35 A key factor contributing to the impoverishment of Iran’s lower classes has been sanctions. Although sanctions have been aimed at ratcheting up the pressure on the political elites, too often, they have caused severe economic crises for the country at large while largely harming ordinary Iranians. Similarly, household income and consumption have been adversely affected.

The effect of sanctions on Iran’s economy has been twofold; it has both reduced government revenues from oil exports and Iran’s trade with the outside world. The decline in export earnings has led to the devaluation of Iran’s national currency, rising inflation, and hitting household budgets. The decline in government revenues has, in turn, led to a recession that has hurt both consumption and employment. A household consumption survey shows that per capita spending has declined since 2010 and has dropped even further as the U.S., under the Trump Administration, pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 and launched a “maximum pressure” campaign.

The effects of the economic crisis created by the sanctions have not been evenly distributed, with rural households having been hardest hit by the crisis. Since 2010, the poverty rate in rural areas has doubled, and in urban areas, it has increased by 60 percent. Unlike 2011, when the emerging cash subsidy program protected the poor from the negative consequences of tougher sanctions under President Obama, in the ensuing years (2019-2020), Iran’s welfare organizations and the financial assistance program have been severely weakened. They have failed to prevent a sharp fall in consumption rates across the country’s social spectrum and the soaring poverty rates. Since 2011, the income of approximately 8 million middle class citizens have shrunk, swelling the ranks of the poor by more than 4 million.36

Impact of Sanctions on Iran’s GDP

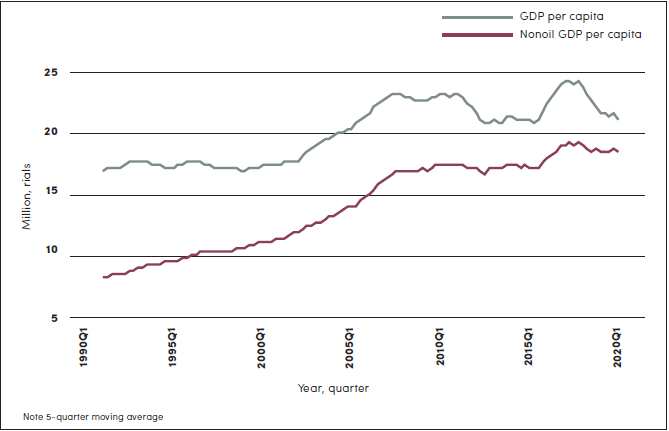

President Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy has had devastating consequences for Iran’s gross domestic product (GDP), sharply declining and strangulating the country’s economy. Aside from these sanctions, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted massive damage on Iran’s economy. The U.S. sanctions, which have reduced Iran’s oil exports and foreign trade, have dealt a severe blow to Iran’s economy, resulting in a catastrophic drop in the living standards of ordinary people. Regarding to the figure 1, in the short period between the reduction of sanctions in 2016 and their re-imposition in 2018, Iran’s economic growth (GDP growth) sharply declined from 13 percent per year to minus 6 percent show a worse picture, with the average standard of living falling by 17.7 percent during 2010-2019. As a result, per capita consumption in 2019 was back to 2002 level. The figure also shows the increase in non-oil GDP per capita. Even with declining oil revenues after 2010, this rate has been on the rise. Personal consumption data obtained from expenditure surveys.37

Figure 1: GDP and Non-Oil GDP per Capita, 5-Quarter Moving Averages

Source: Djavad Salehi-Isfahani (2020)38

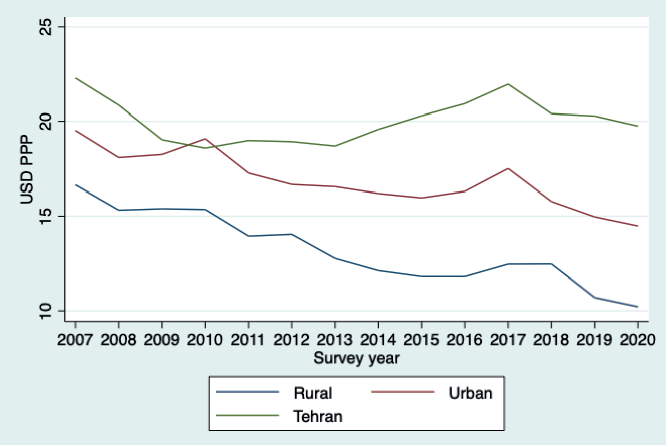

Impacts of Sanctions on Standard of Living

Despite the government’s efforts to address the issue of poverty through cash and non-cash assistance, the economic conditions have deteriorated in the last two years, especially in rural areas. During the period 2011-2012, government cash assistance slightly reduced the impact of Obama sanctions, and the poverty rate actually fell. In 2018, however, with the re-imposition of new sanctions, cash assistance failed to help households due to inflation, and the poverty rate in the country increased as a result. The average standard of living fell by 17.7 percent between 2010 and 2019. Consequently, per capita consumption in 2019 returned to 2002 levels. The economic crisis has not only prevented the Iranian people from raising their living standards since 2010 but has almost completely erased the results of a decade of progress.39

The economic crisis has not only prevented the Iranian people from raising their living standards since 2010 but has almost completely erased the results of a decade of progress

Figure 2: Real Expenditures per Person per Day (2020 Prices)

Source: Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, (2021)40

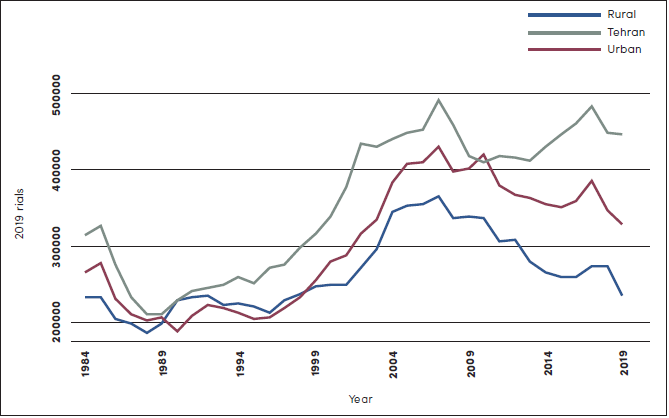

Figure 3: The Rise and Fall of Living Standards

Source: Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, (2020)41

Consumption of different social classes has also been seriously damaged as a result of sanctions. Figure 3 shows the average per capita expenditures of Tehran and other urban areas, which are adjusted according to the consumer price index for rural and urban areas and the cost of living index obtained from the poverty lines of rural and urban areas of all provinces. According to this index, although all regions have benefited from pre-2010 economic growth, largely due to increased oil revenues, the economic contraction has not been evenly distributed. All sectors have been hit hard since the temporary drop in oil prices in 2008, which was quickly followed by rising sanctions. While in Tehran, the average consumption remained almost constant after 2008, in the rest of the country, it decreased sharply by nearly 30 percent in rural areas and 11.6 percent in other urban areas (Figure 2).42

Government employees’ jobs have been better protected during this crisis than in other sectors. Rural and smaller areas have benefited the least from government support. These areas were more geographically and politically distant from the centers of power and the national treasury and therefore benefited less from the government’s social protection policies. The figure 3 also shows all three regions experienced a short recovery after the nuclear deal (JCPOA) went into effect in 2016, a positive blip in the otherwise depressing picture of living standards that is hard to square with some claims in Iran that all of Iran’s economic problems are due to the JCPOA.

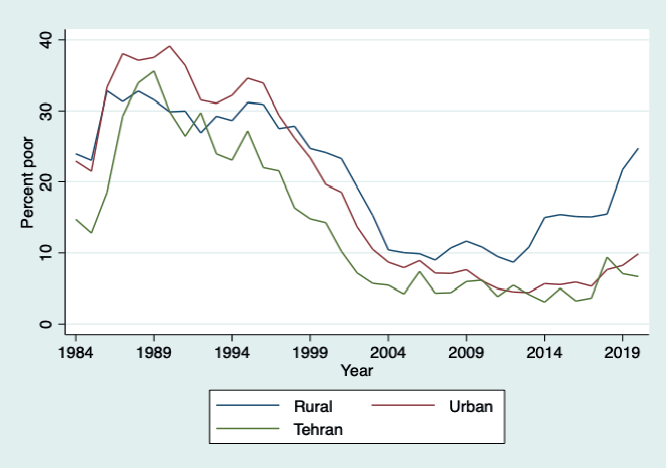

The Impact of Sanctions on Poverty Rate

In 2019, out of 10 million people described as poor, 4.8 million lived in rural areas, 4.4 million in urban areas, and less than 1 million in the capital city, Tehran. In all three areas, poverty rates follow the path of rising and falling average living standards (Figure 4). Poverty in rural areas is higher and more volatile than in urban areas and Tehran. It should be noted, however, that all regions experienced declining poverty rates between 2000 and 2007, when oil revenues were high and rising.43

Poverty rates were relatively stable and low until 2012, when the value of the Iranian currency collapsed under the pressure of Obama’s sanctions, after which it began to rise. The impact of Ahmadinejad’s 2010 subsidy program on poverty reduction in 2011-2012 can be seen despite the tightening of sanctions. After 2012, all poverty rates continued to rise, while rural poverty rates grew faster than in other areas. The deepening economic crisis following the launching of a “maximum pressure” campaign implemented by the Trump Administration can also be seen in the rapidly rising poverty rate across the country from 8.1 percent in 2017 to 12.1 percent in 2019. The four percent increase meant that another 3.2 million Iranians had fallen below the poverty line in two years.44

In general, in the middle of the 2000s, the lower six deciles reach a total of 30 percent of national income. The share of the lower two deciles is about 5.5 percent. In recent years, the richest decile has earned about 14 times as much as the poorest decile.45 The population below the absolute poverty line reached 15 percent from 2013 to 2017 but increased to 30 percent from 2017 to 2019.46 A report entitled “Poverty Monitoring,” published by Iran’s Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare in the summer of 2021, indicated that in 2020 the per capita poverty line, with an average growth of 38 percent compared to the previous year, had reached one million and 254 thousand tomans ($ 6). Expenditure and income figures in this report show that in 2019, one-third of Iranian households lived below the poverty line.47 While growing poverty became a pervasive trend in the lower six deciles, it also increasingly characterized the living conditions of those in the third to sixth deciles. Given that the middle class makes up approximately 35 percent of Iran’s population, the epicenter of poverty –emblematic of the ongoing economic decline– continues to be clearly the fourth decile. The situation in the first to third deciles has also dramatically grown worse.48

Figure 4: Poverty Rates by Region (1984-2019, Percent)

Source: Djavad Salehi-Isfahani,(2021)49

The Impact of Sanctions on the Middle Class

The economic crisis has also adversely affected the well-being of the country’s middle class. While the number of people below or near the poverty line is significant because they have the least ability to cope with declining incomes, the size of middle-income groups affected by sanctions has significantly increased. While the poor are eligible for various types of government assistance, middle-income groups are not, as they should rely solely on their source of income.

While the poor are eligible for various types of government assistance, middle-income groups are not, as they should rely solely on their source of income

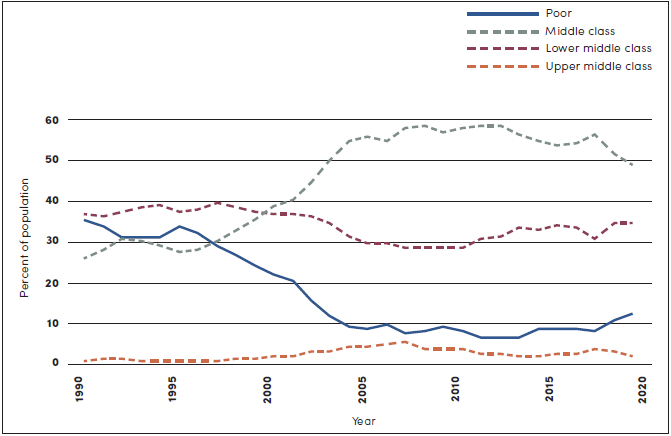

Groups at the lower levels of the middle class are not sufficiently shielded from the poverty line so as to maintain their current status if the financial crisis deepens. Therefore, they are just as vulnerable as the poor and need social protection in a deteriorating economic situation. The main concern about the status of the middle class, which is those who are well above the poverty line and do not run the risk of becoming poor, is the damage to their long-term socio-economic development. Since the escalation of sanctions in 2011, the middle class share has fallen by nearly 10 percent, from 58.4 percent in 2011 to 48.8 percent in 2019. This means that some eight million people of the middle class have suffered economic fallout from the disparate impact of these sanctions (Figure 5).50

Figure 5: The Evolution of Income Classes (1990-2019)

Source: Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, (2021)51

Trump’s maximum pressure campaign in May 2018 reduced Iran’s oil exports to a trickle and froze 90 percent of all the reserves Iran had abroad ($122.5 billion in 2018, according to the IMF).52 Growth took a dive, from +7 percent to -6 percent. The impact of this reversal on ordinary people’s living standards was dramatically visible.53 At present, it is estimated that the middle class makes up approximately 35 percent of Iran’s population of 85 million –that is nearly 30 million. According to one study, almost half of them live below the poverty line.54

Perhaps the impact of sanctions has been most discernible in the case of women’s ability to claim and enjoy their human rights. Today, as many leading Iranian women observe, Iran’s “middle class woman” has become a disappearing category. “Although women outnumber men in university enrollment, they often graduate to find that employers prefer to hire men.”55 The dismantling of Iran’s economy and its people’s livelihood has been transpiring in the lives of the very constituency that has been working for reform, democratic rights, and liberalization, and in whose name the Trump Administration officials spoke: “Middle class Iranian women.” The vicious sanctions imposed on Iran thus far have significantly diminished women’s fragile gains in employment, upper management positions, and leadership roles in the arts and higher education and, more importantly, have undermined their capacity to seek legal reforms and protections.56 Faezeh Tavakoli, a historian with the Institute of Humanities and Cultural Studies in Tehran, echoes a similar sentiment: “The pressure on women, on the middle class, is utterly oppressive. I just don’t find the justifications for sanctions at all persuasive, certainly not from a feminist perspective. You can’t tell people, ‘starve’ and then seek freedom.”57

The Gradual Erosion of the Modern Middle Class: Some Implications

Today, the modern middle class in Iran is economically close to the lower class of society, and its demands are primarily economic and not political development. Gholamhossein Shafei, head of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, opines that the fifth and sixth deciles of the middle class have become poor and that the country’s middle class is fast disintegrating.58 Currently, among graduates of higher education, 1,185,294 are unemployed, of whom 224,435 have associate degrees, 797,375 have bachelor’s degrees, 158,309 have master’s degrees, and 5,175 have doctorates.59

Today, the modern middle class in Iran is economically close to the lower class of society, and its demands are primarily economic and not political development

The deteriorating economic situation of the modern middle class led to the results of the recent parliamentary election (February 21, 2020), which, with 42.5 percent, marked the lowest rate of participation in the past eleven rounds of the Islamic Consultative Assembly elections. Economic insecurity, the main cause of the protests of November 2019, was a tipping point in the diminishment of participation in the elections. The conservatives won a decisive majority of seats (three-quarters) in parliament due in large part to the fact that many reformists refused to run, and also a great number of reformists were also disqualified from doing so by the Guardian Council. This issue was more evident in the city of Tehran than in other cities, where all 20 representatives from the capital city belonged to the extremist conservative camp.

While middle class protesters in 2009 demanded political development and basic freedoms, the November 2019 protesters, led largely by the poor classes, voiced their economic concerns. The protesters’ slogans contained no references to freedom, civil society, or political development but rather reflected their disappointment with economic insecurity. Some of them even expressed outright support for Reza Shah (the first Pahlavi king), whose benevolent dictatorship was founded upon building infrastructure and addressing the country’s modernization imperatives.

Unlike the reformists, those who voted for Raisi see the consolidation of power as a positive sign, as this has placed all the levers of powers, including the executive, the parliament, and the judiciary, in the hands of conservatives. This monopoly of power by the conservative camp not only renders the middle class unrepresented in the national power structure it also makes their return to power in the coming years all the more difficult. It is equally important to realize that the economic pressure following President Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA and the imposition of new sanctions on Iran has made the situation for Iran’s middle class much worse. In 2018, with the start of sanctions and the ongoing mismanagement of the economy, the country faced a negative growth rate of 5 percent.

Consider, for example, widespread protests that began on July 15, 2021, in different cities of Iran, demanding accountability from officials over repeated power cuts and water shortages. These protests were and continue to be a backlash to government mismanagement and climate-related crises, including extreme drought, dust storms, and an unprecedented heatwave. Protesters have been chanting anti-government slogans while denouncing the country’s leadership amid severe water shortages in southwestern parts of the country. Other cities and provinces have joined these protests, which were preceded by labor unrest and ongoing strikes by oil workers in Khuzestan province. Thus far, Iran’s middle classes have seemingly refrained from participating in these street protests. If, however, these demonstrations sustain over time, the possibility of middle classes taking part in them will likely enhance. This outright display of anger and frustration directed at government mismanagement will likely test Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi.60

These developments demonstrate that a growing number of the middle class members have turned their attention away from political development and toward economic issues. The weakening of the middle class will hold negative consequences for the country’s foreign policy. Western scholars, such as Norris M. Ripsman, point out how domestic support for regional détente, improvement of relations with the West, and adapting to globalizing forces proved crucial during the Khatami presidency.61 As the largest social class in Iran, the middle class was the most powerful voting bloc in the 1997 elections that brought Khatami to power. At that time, this class made up only 30.5 percent of the population and nearly 56.1 percent of the educated population of voting age –namely those older than 16 and with at least a high school education. By 2011, the middle class had doubled their share of the population to nearly 60 percent and of educated voters to approximately 81 percent.62 Before the victory of Khatami, the increasing economic hardship caused by the ongoing sanctions had convinced Iran’s middle class that political accommodation with the West and integration into the global economy might provide solutions to the country’s economic bottlenecks. The ruling elites found opening the door to global markets, foreign direct investment, and technology transfer immensely appealing.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s victory in 2005 introduced a new chapter in Iran’s foreign and domestic policies. Unlike his predecessors, Ahmadinejad utilized the attractive platform of social justice for the downtrodden, who had felt neglected and marginalized for some time, and expressed great resentment against rising inequality and poverty. Resorting to a populist platform, Ahmadinejad popularized a “look to the East” foreign policy as the negotiation with the EU-3 failed to yield a desirable outcome for Iran. This anti-Western approach resonated deeply with the earlier years of the revolution.63

Hassan Rouhani came to power as a result of the participation of the middle class in the 2013 and 2017 elections. Rouhani had strong middle class support in the 2013 election. In the first round, he won against six other candidates with 51 percent of the vote, and in the second round, he won 57 percent of the vote against his powerful rival, Ebrahim Raisi. Rouhani was backed by a base of the new middle class and campaigned on resolving the nuclear issue with the West. But the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the JCPOA and the imposition of a broad array of new sanctions on Iran weakened the middle class in Iran while also undermining Rouhani’s Administration beyond repair.

Since 2011, the economic conditions of approximately 8 million people belonging to the middle class have significantly diminished, resulting in a considerable decline in popular support for moderate parties and less favorable views toward integration into the global economy. Perhaps more important has been the eroding support for the JCPOA from 80 percent to 50 percent. The Rouhani administration was blamed for the deteriorating economic conditions. This backlash was apparent in comments made by Alireza Zakani, the Conservative candidate in the 2021 presidential election, who eventually withdrew in favor of Ebrahim Raisi while noting immediately after Raisi’s victory that: “The era of pro-Western elements in the country is over.”64

One clear implication of this reorientation of Iran’s foreign policy has been the resurrection of the “look to the East” policy and strengthening relations with China and Russia. At the same time, the talk of normalization of relations with the West in an effort to strike a proper balance between the East and the West, a position once very popular among the members of the middle class, has fallen by the wayside.65 In his first press conference after winning the election, Ebrahim Raisi underscored the importance of economic ties with China and downplayed the possibility of meeting with American President Biden. Raisi was abundantly clear: “There are many capacities between Iran and China, and we will definitely work to revive these capacities. We have very good relations with China, and in the field of foreign policy, the implementation of the comprehensive plan as one of the documents and agreements between the two countries will definitely be on the agenda.”66

What Lies Ahead

Iran’s reformists were a party of imagined politics and democratic change of the not too distant past. Today, however, a painful question persists: What happened? The Pahlavi era spawned modernizing programs that led to the emergence of a new middle class in Iran, which, in turn, played a significant role in advancing those programs. The growing visibility of this new middle class in Iran’s politics after the 1979 Iranian Revolution reflected a larger shift in the mindset of this class, away from apathetic indifference and toward great enthusiasm for and concern with politics. The aspiration of this class became closely associated with advancing democratic demands and ideologies within the Iranian political context. Although the key aspiration of this class was rarely economic, it certainly had a great stake in the country’s economic prosperity. On balance, however, Iran’s middle class was primarily driven by its longing for political, social, and cultural changes.

The Pahlavi era spawned modernizing programs that led to the emergence of a new middle class in Iran, which, in turn, played a significant role in advancing those programs

In post-revolutionary Iran, members of the new middle class have developed a deeper interest in political development than other social classes, owing in large part to their professions. They remain culturally competent and socially sensitive to broader societal issues. This reality may, in part, explain why this class has consistently defended democratic reform. During the Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911), for instance, the upper classes (princes and nobles) and the lower classes (farmers and peasants) played little or no role in the revolutionary change. It was the middle class on whose shoulder the lion’s share of the burden of confronting the authoritarian regime fell. Similarly, in the 1979 revolution in which a broad array of social forces and classes participated, it was the middle class that took up the mantle of leadership in the hope of establishing a democratic system following the collapse of the Pahlavi regime.

In recent years, middle class income has dramatically plunged, compelling many of its members to prioritize economic security over political reform. The implementation of the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran after Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA put a massive strain on Iran’s economy, further worsening the country’s already deteriorating economic conditions while also contributing significantly to the decline of middle class income. In 2018, the imposition of new sanctions further exacerbated Iran’s mismanaged economy. With the country’s economy in dire straits, reformists saw middle class support for their camp slowly slipping away‒broad-based support widely regarded as vitally important social capital. At the same time, reformists’ domestic and foreign policy stances came under heavy criticism, with their economic performance lambasted by critics in general but by the conservative camp in particular.

In recent years, middle class income has dramatically plunged, compelling many of its members to prioritize economic security over political reform

The slow demise of Iran’s middle class was –and continues to be– attributed in no small part to ongoing U.S. sanctions. These unrelenting punitive economic sanctions have weakened Iran’s middle class, and civil society marginalized the reformist camp and fortified the authoritarian nature of Islamic populism over the past four decades.67 In the face of ongoing U.S. sanctions and the declining role of the middle class, Iran’s current ruling elites and the Revolutionary Guards will most likely turn toward implementing the “look to the East” project –a deeply troubling foreign policy recalibration that has gained much traction among the conservatives in recent years.

Unless the U.S. and its European allies take effective and sustainable initiatives to counter Beijing’s policies and commit Tehran to a long-term pact, we may be witnessing the falling of Iran into a long-term authoritarian cycle from which no escaping would be easy in the near term. The Islamic Republic is seemingly preparing for such a long game, especially at a time when it faces no formidable challenges from its middle class –a class that, for all practical intents and purposes, has lost its strong appetite for the pursuit of accountability and democratic ideals for societal change. We could take the relentless U.S. sanctions on Iran as an occasion to ask whether such a policy has precipitated the death of Iran’s reformist camp as well as the imagined political ideals of its middle class. While it is wrong to understate the role that Iran’s internal political and economic dynamics –economic mismanagement, endemic corruption, and the COVID-19 pandemic– have played in mitigating the power of its middle class, it is equally misguided to presume that U.S. sanctions were secondary in relation to the shrinking of Iran’s middle class.

Finally, another reason why the reform movement has failed can be attributed to the actions of quasi-reformists actors in the parliament and government. The performance of such reformists and their gradual removal from power over the past few years, as well as the presence of reformists in power who were not the true representatives of the middle class, has led to the conspicuous lack of middle class participation in recent elections. Raisi’s rise to power has been emblematic of the increasing erosion of the reformist movement in Iran.

Endnotes

1. John Halpin and Marta Cook, “Social Movement and Progressivism,” Center for American Progress, (April 14, 2010), retrieved June 27, 2021, from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/democracy/reports/2010/04/14/7593/social-movements-and-progressivism/.

2. Maral Karimi and Vahid Yücesoy, “The Reformist Project in Iran Is Dead,” Al Jazeera, (October 5, 2018), retrieved July 2, 2021, from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2018/10/5/the-reformist-project-in-iran-is-dead.

3. Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “The Dilemma of Iran’s Resistance Economy,” Foreign Affairs, (March 17, 2021), retrieved June 29, 2021, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2021-03-17/dilemma-irans-resistance-economy.

4. Statistical Center of Iran, retrieved May 10, 2020, from https://www.amar.org.ir.

5. “General Census of Population and Housing 2016,” Statistical Center of Iran, retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.amar.org.ir.

6. “General Census of Population and Housing 2016.”

7. Statistical Center of Iran.

8. “General Census of Population and Housing 2016.”

9. Gholamreza Iraqi, “The New Middle Class and Its Effects in the Period after the Islamic Revolution,” (February 20, 2009), retrieved October 10, 2020, from www.farnews.com/printable.php?nn-8710040355.

10. Valentine M. Moghadam, “Iranian Women, Work, and the Gender Regime,” The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, (Spring 2018), retrieved July 2, 2021, from https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/iranian-women-work-and-the-gender-regime/.

11. “Females Outnumber Males In Iran’s 2017 University Entrance Exam,” Tehran Times, (September 16, 2017), retrieved July 2, 2021, from https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/416821/Females-outnumber-males-in-Iran-s-2017-university-entrance-exam.

12. On a related discussion on the narrowing gender gap in education and its impact on the Iranian family; see, Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “The Iranian Family in Transition,” in Mahmood Monshipouri (ed.), Inside the Islamic Republic: Social Change in Post-Khomeini Iran, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 133-150.

13. “Iran’s Literacy Rate Reached Up to 96.6%,” Tehran Times, (January 27, 2021), retrieved July 4, 2021, from https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/457448/Iran-s-literacy-rate-reaches-up-to-96-6.

14. Quoted in “Iran Literacy Rate at 96%,” Financial Tribune, (February 5, 2020), retrieved July 4, 2021, from https://financialtribune.com/articles/people/102038/iran-literacy-rate-at-96.

15. Nadereh Chamlou, “COVID-19 Depressed Women’s Employment Everywhere, and More so in Iran,” Atlantic Council, (April 29, 2021), retrieved July 2, 2021, from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/covid-19-depressed-womens-employment-everywhere-and-more-so-in-iran/.

16. Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Religious Modernists and the ‘Woman Question,’” in Eric Hooglund (ed.), Twenty Years of Islamic Revolution: Political and Social Transition in Iran Since 1979, (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2002), pp. 74-95; see, p. 95.

17. Nayereh Tohidi, “Women’s Rights and Feminist Movements In Iran,” International Journal on Human Rights, No. 24 (December 2016), retrieved February 28, 2021, from https://sur.conectas.org/en/womens-rights-feminist-movements-iran/.

18. Quoted in Azadeh Kian-Thiebaut, “Women and the Making of Civil Society in Post-Islamist Iran,” in Hooglund (ed.), Twenty Years of Islamic Revolution, pp. 56-73; see, p. 62.

19. Alireza Azghandi, An Introduction to Iranian Political Sociology, (Tehran: Qomes Publishing, 2006),

pp. 131-132.

20. Statistical Center of Iran, Reports of Ministry of Science.

21. “How Many Faculty Members Are There in the Country?” Institute for Research and Planning in Higher Education (IRPHE), (January 6, 2019), retrieved April 10, 2020, from https://irphe.ac.ir/content/1943.

22. Gholamreza Iraqi, “The New Middle Class and Its Effects in the Period after the Islamic Revolution,” Frarnews, (February 20, 2009), retrieved October 10, 2020, from www.farnews.com/printable.php?nn-

8710040355.

23. Azghandi, An Introduction to Iranian Political Sociology, p. 131.

24. “Statistics and Information of the Employees of the Executive Organs of Iran,” Administrative and Recruitment Affairs Organization of Iran, retrieved May 10, 2020, from https://www.aro.gov.ir.

25. “Statistics and Information of the Employees of the Executive Organs of the Country,” Administrative and Recruitment Affairs Organization of Iran, (December 20, 2018), retrieved July 26, 2021, from https://www.aro.gov.ir/FileSystem/View/File.aspx?FileId=e99860a9-cef0-4ebc-b706-26d8ed34765a.

26. Alireza Azghandi, Introduction to the Sociology of Iran, (Tehran: Qomes, 2005), p. 132.

27. “What Percentage of Iranian Households Have a Car?” Eghtesadonline, (November 28, 2019), retrieved July 3, 2021, from https://www.eghtesadonline.com./.

28. “Results of the General Census of Population and Housing for Years 1987, 1997, 2007,” Statistical Center of Iran, retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://www.amar.org.ir.

29. “Results of the General Census of Population and Housing for Years 1987, 1997, 2007,” Statistical Center of Iran, retrieved May 10, 2020, from https://www.amar.org.ir.

30. Jean-Pierre Digard, Bernard Hourcade, and Yann Richard, Iran in the Twentieth Century, translated by Abdolreza Hoshang Mahdavi, Vol. 2, (Tehran: Alborz Publication, 1999), p. 422.

31. Sadegh Ziba Kalam, “The Causes of Coming into Power of Khatami (Reform Government 1997/1376) on the Basis of Samuel Huntington’s Theory of Uneven Development,” Quarterly Journal of Political and International Research, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Summer 2010), pp. 51-76, see especially pp. 66-67.

32. Ali Darabi, Electoral Behavior in Iran, Patterns and Theories, 1st ed., (Tehran: Soroush Publications, 2009), p. 43.

33. Amir Niakoei, “Sociology of Political Conflicts in Iran Election 2005,” Journal of Political Science, No.1 (Winter 2014), pp.199-230, see especially pp. 217-220.

34. “2021 Election; The Participation Rate Was 48.8 Percent,” BBC News, (June 19, 2021), retrieved fromhttps://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-57539695.

35. Nazli Kamuri, In the Middle, in the Margins: About the Poor Layers of the Middle Class in Iran, (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Zamaneh Media, 2021).

36. Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “Iran’s Middle Class and the Nuclear Deal,” Brookings, (April 8, 2021), retrieved February 12, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/04/08/irans-middle-class-and-the-nuclear-deal/.

37. Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “Iran Under Sanctions: Impact of Sanctions on Household, Welfare and Employment,” Rethinking Iran, (2020), retreived February 12, 2022, from https://www.rethinkingiran.com/iranundersanctions/salehiisfahani.

38. Isfahani, “Iran under Sanctions.”

39. Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “Tyranny of Numbers: Rising Poverty and Falling Living Standards in Iran in 2020,” DjavadSalehi.Com, (August 28, 2021), retreived from https://djavadsalehi.com/2021/08/28/rising-poverty-and-falling-living-standards-in-iran-in-2020/.

40. Isfahani, “Tyranny of Numbers.”

41. Isfahani, “Iran under Sanctions.”

42. Isfahani, “Iran under Sanctions.”

43. Djavad Salehi Isfahani, “Iran: The Double Jeopardy of Sanctions and COVID-19,” Brookings, (September 23, 2020), retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/iran-the-double-jeopardy-of-sanctions-and-covid-19/.

44. Djavad Salehi Isfahani, “Iran’s Economy 40 Years after the Islamic Revolution,” Brookings, (March 14, 2019), retreived from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/03/14/irans-economy-40-years-after-the-islamic-revolution/.

45. Mojtaba Nazari, “What Is the Rich and Poor Gap in Iran and the World?” Bourseon, (June 29, 2021), retreived from https://bourseon.com/VkMn.

46. “The Report on the Situation of Poverty and Inequality in the Country in the Last Two Decades Will Be Unveiled,” IlNA News Agency, (June 2, 2021), retreived from https://www.ilna.news/fa/tiny/news-1085068.

47. “Collection of Poverty Monitoring Reports,” Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare, (Summer 2021), retreived from https://poverty-research.ir/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16.pdf.

48. Mohammad Reza Nikfar, “Iran’s Middle Class and Its Poor Layers,” in Nazli Kamuri, In the Middle, in the Margins - About the Poor Layers of the Middle Class in Iran, (Publication: Zamaneh Media, 2021), p. 56.

49. Isfahani, “Tyranny of Numbers.”

50. Isfahani, “Iran’s Middle Class and the Nuclear Deal.”

51. Isfahani, “Iran’s Middle Class and the Nuclear Deal.”

52. Mohammad Reza Nikfar, “Iran’s Middle Class and Its Poor Layers,” p. 37.

53. Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “Tyranny of Numbers: Five Figures Show the Losers and Winners of Economic Growth Under Different Presidents of The Islamic Republic,” (May 2, 2021), retrieved from https://djavadsalehi.com/2021/05/02/five-figures-show-the-losers-and-winners-of-economic-growth-under-different-presidents-of-the-islamic-republic/.

54. Isfahani, “Tyranny of Numbers.”

55. Azadeh Moaveni and Sussan Tahmasebi, “The Middle-Class Women of Iran Are Disappearing,” The New York Times, (March 27, 2021), retreived from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/27/opinion/sunday/iran-sanctions-women.html.

56. Moaveni and Tahmasebi, “The Middle-Class Women of Iran Are Disappearing.”

57. Moaveni and Tahmasebi, “The Middle-Class Women of Iran Are Disappearing.”

58. “Shafei: The Middle Class of the Country Is Disintegrating,” ISNA News Agency, (June 7, 2020), retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://www.isna.ir/news/99031810374.

59. “General Census of Population and Housing 2016.”

60. Kareem Fahim and Miriam Berger, “Protests Over Water Shortages in Iran Turn Deadly in Summer of Drought and Rolling Blackouts,” The Washington Post, (July 21, 2021), retrieved July 25, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/iran-protests-water-shortage-khuzestan/

2021/07/21/4f2c1fba-ea23-11eb-a2ba-3be31d349258_story.html.

61. Norrin M. Ripsman, “Neoclassical Realism and Domestic Interest Groups,” in Steven E Lobell, Norrin M Ripsman, Jeffrey W Taliaferro (eds.), Neoclassical Realism, the State, and Foreign Policy, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp.170-193, see especially p. 180.

62. Isfahani, “Iran’s Middle Class and the Nuclear Deal.”

63. Alireza Azghandi, Frameworks and Orientations of Foreign Policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, (Tehran: Qomes Publishing, 2009), p. 140.

64. Alireza Zakani, “The Era of Westerners in the Country Is Over,” Mehr News Agency, (June 22, 2021), retrieved June 26, 2021, from https://www.mehrnews.com/news/5241395.

65. For further analysis on the prospects for the Iran-China relations; see, Mahmood Monshipouri and Javad Heiran-Nia, “China’s Iran Strategy: What Is at Stake?” Middle East Policy, Vol. XXVII, No. 4 (Winter 2020), pp. 157-172.

66. Ebrahim Raisi, “The Situation Is Changing in Favor of the People / Our Foreign Policy Is not Limited to the JCPOA,” ISNA News Agency, (June 21, 2021), retrieved June 26, 2021, from https://www.isna.ir/news/1400033123849.

67. For more on that, see, Mahmood Monshipouri and Manochehr Dorraj, “The Resilience of Populism in Iranian Politics: A Closer Look at the Nexus between Internal and External Factors,” The Middle East Journal, Vol. 75, No. 2 (Summer 2021), pp. 201-221.