Introduction1

Over the past ten years, evident progress has been made in the study of Orientalism in Imperial and Soviet Russia. A real breakthrough in this field occurred in 2005 and again in 2010-2011. In 2005, a heated discussion in the journal Kritika established different manifestations of Orientalism in Russia from the 18th through the early 20th centuries.2 After the pioneering works of David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Vera Toltz, Michael Kemper and Svetlana Gorshenina,3 nobody doubts that the academic schools of Russian/Soviet Orientology, centered in Saint Petersburg and Moscow, shared the general premises of philological and sociological Orientalism, according to Edward Said’s classification, although they had deviations from the classical European model. Yet there are still numerous blank spots in the field. Regional centers of Oriental studies remain under-examined, and a mosaic palette of schools and disciplines in Russia’s Orientology is poorly presented in the debates of Orientalism. It is noteworthy that apart from philology and history, Russia’s Orientalism includes philosophy, ethnography, archeology, numismatics, area studies and political science. There was also an influential school of missionary Orthodox Orientology addressed to Old Believers, Muslims, Buddhists and different pagan faiths, and centered in Kazan until 1921. Its niche in the Soviet Union was taken up by militant and later scientific atheists. In addition, there were military and diplomatic translators from Oriental languages as well as experts in the Russian and foreign Orient in the structure of the secret police and the intelligence service of the imperial Ministry of the Interior and the Soviet Cheka-NKVD-KGB.

In order to honor the constitutional right to religious beliefs, and to avoid the impression that the Soviet state actively persecuted religion, the Bolsheviks charged allegedly non-governmental social organizations with the struggle against religion

On these pages, I will examine the making of the intolerant discourse on Islam in Soviet and Imperial Russia by amateur and trained historians, philosophers and ethnographers, and attempt to integrate applied Oriental studies into the general debates on Orientalism. The focus is on the agents and networks of the state atheistic propaganda complex, as well as on its changing language, topics and messages. To some degree, the lack of previous attention to non-academic versions of Orientalism reflects their disregard by the imperial and Soviet academic schools of Orientology in Saint Petersburg-Leningrad that did not consider them worthy of “true scholarship,” although the academics sometimes did their work for the state. It will become clear in this article that they much contributed to the development of Russian Orientalism over time. Chronologically, the article covers the whole period of Soviet anti-Islamic agitation from the late 1920s to the end of the 1980s. Special attention is paid to similarities and differences between the interwar and post-war atheistic discourses and practices. In addition, I discuss the relation of Soviet atheistic activities to late imperial Orthodox missionary work, and to post-socialist Islamic appeal (da’wa) in the region.4

Islamic Studies in Godless Associations

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Islam attained equal rights with the Russian Orthodox Church, but lost the protection of the new secularist state.5 The Bolsheviks feared and hated religion, and declared it alien to the socialist polity. Already the famous decree of January 23, 1918, “On the Separation of Church from State and School from Church,” proclaimed Russia a secular state, denied the legal standing of all confessions, and banned all instruction of religion outside private homes. From the 1920s through the mid-1980s, Soviet confessional policy swung from repression to relative tolerance, but the regime maintained a general hostility toward religion until the middle of the 1980s.6 In order to honor the constitutional right to religious beliefs, and to avoid the impression that the Soviet state actively persecuted religion, the Bolsheviks charged allegedly non-governmental social organizations with the struggle against religion.

There were two All-Union umbrella associations of this sort in Soviet Russia. The first of these was called the “League of the Militant Godless” (Soiuz voinstvuiushchikh bezbozhnikov, or SVB). The ambitious and saucy name of the League corresponded well with the style and character of anti-religious propaganda in the turbulent and bloody interwar years. Its message was to deracinate all confessions; since 1929 the badges of League members have carried the slogan, “The Struggle against Religion is a Struggle for Socialism!” Nominally, the League existed for twenty-two years (1925-1947), although the campaign against religion was moderated on the eve of World War II and the League was not allowed to conduct a militant anti-religious propaganda from 1940 on. The most active periods of the SVB were the years of the Great Turn and the Cultural Revolution in 1929-1934, and then again in 1938-1940. In 1947, the SVB was replaced by the “All-Union Society for the Promotion of Political and Scientific Knowledge” (Vsesoiuznoe obshchestvo po rasprostraneniiu politicheskikh i nauchnykh znanii), which shortened its name to the “Knowledge Society” (Obshchestvo Znanie) in 1963. The latter survived the Soviet Union in Russia but lost its anti-religious branch in 1991.7

In some respects, both associations resembled each other. They were funded by the state and charged with helping to implement the All-Union state projects. Both associations were engaged in official propaganda work, whose forms included public anti-religious lectures, Sunday and people’s universities, as well as exhibitions, broadcasting and documentaries devoted to major religious festivals and ceremonies. In addition, local departments of the SVB provided the state with statistical data on closed and still functioning mosques and prayer houses, holy places in the countryside. From 1923, League members specialized in atheist propaganda against Sunni Islam periodically consulted the Komsomol functionaries on the manners and customs of Muslim peoples to organize anti-religious carnivals on the days of religious festivals usually called “Komsomol bayram.”8 In the early 1930s, the SVB “ordered” ethnographers through the Presidium of the Soviet Academy of Sciences to produce a lexicon of “Religious Beliefs of the Peoples of the USSR.”9 After the Second World War ethnographers helped district and village Soviets to introduce new Soviet festivals, such as First Furrow Day,10 to replace the Muslim feasts with a new Soviet labor culture. Classical “philological Orientalism,” as Edward Said put it,11 in the activities of the Soviet godless associations, was reduced to a more sociological approach to Islam and Muslim societies.

The Knowledge Society inherited the science and atheism museums of the SVB, the first of which had been established in Leningrad in 1931.12 It also built Houses of Scientific Atheism in Moscow, Frunze (today Bishkek) and Tashkent. However, the goals and activities of these associations differed. Militant atheistic propaganda was in the focus of the SVB but later was relegated to a single department of the Knowledge Society charged not so much with atheism but rather with the dissemination of modern sciences. It is noteworthy that there was but one philosopher among eight Soviet chairmen of the Society, the academician Mark Mitin (1956-1960), whose specialty was the criticism of bourgeois philosophy. The other seven chairmen represented the natural and applied technical sciences.13 After the 1930s, religion was expelled from public life and considered less dangerous for the socialist building. Islam was partly legalized in regional muftiates and more tolerated by the Communist Party and state officials. The personnel of both associations was also different. Contrary to the SVB, the Knowledge Society recruited lecturers and other collaborators, not from amateur scholars and pre-revolutionary bourgeois specialists, but from graduates of the Soviet higher school, which had closer relations with universities and institutes in the framework of the Academy of Sciences.

One should not exaggerate the importance of the denunciation of Islam in the USSR. State-sponsored atheism represented only a part of Soviet confessional politics and scholarship. In the 1920s and early 1930s, the situation was extremely diverse. The state first acknowledged Islam, then attempted to eradicate religion in the late 1920s-1930s, moderated its atheistic activities on the eve of the World War II, and again legalized Islam in 1944 in the framework of the regional Spiritual Boards of Muslims supervised from Moscow. In the early 1960s, a new wave of anti-religious repression started.14 According to the fluctuations of confessional politics, the scholarly discourse on Islam was changing. In the early Soviet period, Orientologists from V.R. Rozen’s school like Vasily Bartol’s, their native collaborators and Muslim modernists (jadids), who took on positions in the newly established research institutes and universities, and even some “red Orientalists” regarded Islam as more amenable to modernity than Christianity and found revolutionary potential in it.15 As a rule, scholars and professors from the former imperial universities and academic institutions as well as from the numerous research and educational institutes that appeared in the interwar USSR did not participate in atheistic activities.

From Soviet Orientologists to the Militant Godless

Where did the two godless associations recruit academic volunteers to “storm the heavens”? What kinds of tasks did they set them? The League of the Militant Godless and the Knowledge Society conducted anti-religious propaganda at the grassroots level. If the Soviet official statistics can be trusted, both organizations involved huge masses of the Soviet population. Just seven years after its creation, in 1931, the SVB claimed 5.5 million members, 2 million more than the Communist Party itself.16 It declined to 2 million in 1938 but rose again to 3.5 million in 1941. The Knowledge Society had fewer members but was also a mass organization: in January 1962 it numbered more than 1.1 million members, and this grew to about 2.5 million by the beginning of 1972.17

In order to attract scholarly contributors to their struggle against Islam, the militant atheists had to turn to the Komsomol youth

And yet, the number of trained Orientalists who joined the SVB can be counted on the fingers of one hand. In order to attract scholarly contributors to their struggle against Islam, the militant atheists had to turn to the Komsomol youth –persons from the generations of the 1890s and the 1900s who had graduated from higher schools in the early Soviet years. In the late 1920s and 1930s, these were young, aggressive and ambitious scholars, professors and administrators. Their alma maters were the new educational institutions set up in the 1920s. The “forges for godless cadres” were the Moscow Institute of Orientology (Moskovskii institut vostokovedeniia, MIV, 1921-1954), the Institute of the Red Professorship (Institut krasnoi professury, IKP), the Communist University of Toilers of the Orient (Kommunisticheskii universitet trudiashchikhsia Vostoka, KUTV, set up in 1921) in Moscow, as well as the Oriental Pedagogical Institute (Vostochnyi pedagogicheskii institut, VPI) that emerged in 1922 in Kazan under the patronage of Kazan University’s Faculty of Social Sciences.18

The eminent Soviet Arabist Evgenii Beliaev (1895-1964) and his colleague, the Turkologist Nikolai Smirnov (1896-1983), both graduated from MIV in 1922 and 1924, respectively. Both entered the League of the Militant Godless and produced many contributions about Islam for the association’s popular science editions.19 The Kazakh communist politician and historian Sandzhar Asfendiarov (1889-1938) directed MIV from 1927-1928.20 Among the graduates of the IKP one should mention Arshaluis Arsharuni (1896-1985) and Hadzhi Gabidullin (1897-1940) who collaborated with the SVB in its struggle against “Islamic sectarians” and what were then labeled as pan-Islamist and pan-Turkist movements. The Tatar communist Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev (1892-1940) taught at the KUTV from 1921. In that year he published instructions on the “Methods of Anti-Religious Propaganda among Muslims.”21 Another eminent scholar on this list was the specialist in Marxist philosophy and pre-modern anti-religious movements, Valentin Ditiakin (1896-1956), who lectured at the VPI in Kazan.

Membership in the League of the Militant Godless provided scholars with significant career advantages. Contributors to SVB publications were granted scholarly degrees without defending their dissertations, just on the basis of works published with the help of the SVB. In this way, Smirnov became a Ph.D. (kandidat nauk) in history in November 1935, and Gabidullin obtained the same degree in December of that year.22 Other activists of the SVB made breathtaking careers without any academic degrees. Nikolai Matorin (1898-1936) first studied Egyptology at the Faculty of History and Philology of Petrograd University under the supervision of Professor Turaev. He entered the university in 1917 but in the same year was drafted for military service. He joined the Communist Party in 1919 and became Zinov’ev’s secretary in 1922. The subsequent ups and downs in his career depended much on his personal acquaintance with this influential “Red Mayor” of Petrograd. Matorin lectured at Petrograd University and other institutes from 1922-1926, specializing in the ethnography of religious beliefs and the methodology of anti-religious agitation. The defeat of Zinov’ev’s faction at the 14th Congress of the Bolshevik Party in December 1925 led to Matorin’s exile to Pskov and then to Kazan, where he became deputy chairman of the Tataria’s SVB Central Council. Meanwhile, he studied pagan cults among the Muslim peoples in the Volga region. In 1928, Matorin returned to Leningrad, where he succeeded in becoming deputy chairman at the Institute for the Study of the Peoples of the USSR, and then, in 1930, director of the famous ethnographic museum, the Kunstkamera. At the same time, he headed the Leningrad Province Council of the League of the Militant Godless, where he was charged with providing the scientific basis for the mass repression of “Sectarians,” Orthodox Christians and Muslims. Finally, he fell victim to the new wave of political repression that emerged in 1934-1936.23 Another striking example of a high-ranking militant atheist without a scholarly degree was the infamous Liutsian Klimovich (1907-1989), who fought against Islam for about 60 years, from 1927 to the mid-1980s. He held no top-level posts but remained a leading expert on Islam in both godless associations.24

The League of the Militant Godless also engaged “bourgeois experts” who had previously worked in the Tsarist administration of the borderlands. One of those was Mikhail Tomara (1868-1936?), ex-mayor of Sukhumi, bank officer and financial administrator at large. Tomara was given the opportunity to teach at KUTV, and he collaborated with the Communist International and the SVB. In particular, he participated in the scholarly discussion of the class nature and social basis of early Islam that was initiated by the journal Atheist in 1930.25 Another expert, Asfendiarov, was a military doctor by profession who had graduated from the Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg in 1912.26 But the majority of scholars who engaged in the militant atheistic activities of the SVB were not trained Orientalists or former imperial officials but ethnographers.

After the Second World War, an important shift occurred in the organization of atheistic propaganda: “amateur” militant atheism was replaced by professional scientific atheism

Many of the names, biographies and contributions of the scholars who participated in the activities of the SVB remain to be established. After the Second World War, they mostly changed their field of study, or their very job, and many attempted to forget their godless past by eliminating it from their CVs.27 In addition, a great number of godless oppressors perished, together with targets of their militant denunciation –believers of all confessions, during the political mass repressions from the late 1920s through the 1940s. Their names were not allowed to be mentioned in the press until the fall of the Soviet regime in 1991.

Atheism Becomes a Social Science

After the Second World War, an important shift occurred in the organization of atheistic propaganda: “amateur” militant atheism was replaced by professional scientific atheism. For the first time, this term appeared in the resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, “On Grave Shortcomings in the Scientific Atheistic Propaganda and Measures to Improve Them,” issued in 1954. In response to the resolution, in 1959, a new discipline was introduced into the curricula of higher education, the “foundations of scientific atheism.” To coordinate the work of educators, scholars and propagandists, in 1964 the Central Committee of the CPSU set up an Institute of Scientific Atheism (Institut nauchnogo ateizma, INA) at the Academy of Social Sciences in Moscow. Twice a year the Institute published “Questions of Scientific Atheism” (Voprosy nauchnogo ateizma), with a print run of 25,000 copies. Some former members of the SVB, among them Valentin Ditiakin and Liutsian Klimovich, continued to publish their works at the publishers of the Knowledge Society.28 These veterans, however, were now playing second fiddle. From the 1960s-1980s scientific atheism became the field of study for trained philosophers from provincial pedagogical institutes and universities, including Magomed Abdullaev, Mikhail Vagabov, Serazhutdin Gadzhiev and Irshad Makatov in Dagestan, Vakha Gadaev in Checheno-Ingushetia, and Iurii Petrash in Uzbekistan.29

Militant and scientific atheists were very distrustful of past and present “bourgeois scholars” whom they considered natural enemies of Soviet power, society and scholarship

Separate ethnographers worked for the Knowledge Society as well. The Moscow Institute of Ethnography had a small department on the history of religion and atheism; one of its research fellows, Vladimir Basilov (1937-1998), had previously worked at the Institute of Scientific Atheism (1964-1967) and then became an expert on the cult of Muslim saints in Central Asia. Academic Orientalists in Leningrad and Moscow were allowed to study Islam only outside the Soviet Union. The Moscow Institute of Orientology was closed in 1954, and replaced by the Institute of Oriental Studies in the framework of the Academy of Sciences (IVAN). The Leningrad branch of IVAN, which comprised disciples of the famous academician Krachkovskii, continued to do research on Oriental medieval texts, but the IVAN’s center in Moscow concentrated on the study of contemporary political Islam and the ideology of modern Muslim national movements abroad.30 The Knowledge Society popularized ethnographic and Orientalist works on foreign Islam and the cult of saints for its lecturers.

The Roots of Atheistic Scholarship in Orthodox Missionary Orientology

Both godless associations had a very ambiguous attitude toward scholarship on Islam. On the other hand, militant and scientific atheists were very distrustful of past and present “bourgeois scholars” whom they considered natural enemies of Soviet power, society and scholarship. During the Stalinist repression, activists from the SVB helped the OGPU-NKVD political police in their “hunt” for the “vermin” (vrediteli) and “rootless cosmopolitanism” (bezrodnyi kosmopolitizm) in Islamic studies. In 1931, the Communist Party functionary and historian of Central Asia, Mikhail Tsvibak (Zwieback, 1899-1937) initiated the persecution of the academic school headed by the eminent Orientalist Vasilii Barthold (1869-1930) in Tashkent.31 At the end of the 1940s, Liutsian Klimovich launched an attack on the academician Ignatii Krachkovskii and his school in Leningrad.32 At the same time, however, militant and scientific atheists needed academic Orientologists as providers of knowledge; Klimovich, for instance, referred to Aleksandr Semenov –who was from Barthold’s school– as the recognized authority on the Isma’ilis in Central Asia.33 Barthold’s own works were highly appreciated in Soviet atheistic scholarship.34

Even more striking is the interest of Soviet militant and scientific atheists in the missionary denunciators of Islam in the Tsarist era. The more they attacked pre-revolutionary Orthodox missionaries as “accomplices of the colonial tsarist rule, of the black-hundredists [chernosotentsy] and the reactionaries,” the more they followed them in the choice of their topics, language, and general approach to Islam in Russia. It is noteworthy that from a list of 159 pre-Soviet studies that Beliaev compiled and annotated for use by the SVB propagandists, 39 titles belonged to Orthodox missionary scholarship.35 In 1954, Nikolai Smirnov acknowledged that “there are some interesting pieces among the literature on Islam published by the Orthodox missions,” especially those devoted to “sectarians” (i.e. Sufism and movements which developed out of Islam).36 Liutsian Klimovich and Moscow ethnographer Sergei Tokarev obtained their knowledge of Islam from missionary studies; Smirnov even accused Klimovich of “being tied to the chariot of missionaries who had denounced Islam.”37 In fact, in his atheistic leaflets of the 1920s, Klimovich often quoted implicitly from little-known Orthodox missionary experts on Islam, such as N. Bogoliubovskii and Ia. Koblov.38 It is also easy to detect the direct influence of the Russian missionary tradition in Klimovich’s book Contents of the Qur’an (1930).39

In contrast to pre-Soviet Orientalists and some Orthodox missionaries, militant and scientific atheists did not have a good command of foreign and Oriental languages, with a few exceptions. While it seems that Klimovich and Ditiakin did read in French and German, their successors relied exclusively on the Russian-language literature of the imperial and Soviet periods. That is why Kobetskii, chairman of the Department of Nationalities of the League of the Militant Godless, ordered Beliaev, one of the few atheists with professional training in Oriental and Western languages, to compose his famous “Reader” of extracts from original Muslim sources and Western Orientalist scholarship on the origin of Islam.40 Atheists preferred the old missionary Russian translation of the Qur’an that Gordii Sablukov, from the Kazan Ecclesiastical Academy, had produced at the end of the 19th century. Leningrad Orientalists from Krachkovskii’s school never used Sablukov’s translation, given its inappropriate Orthodox allusions and archaic style. Nevertheless, most scientific atheists –including Klimovich– went on quoting the Qur’an, in Sablukov’s translation, until the 1980s.41

What is already evident is the continuity of late imperial and Soviet Oriental studies with regard to the applied missionary approach to Islam, and in connection with political fears of Islam. Just like their missionary predecessors, the militant and later scientific atheists saw Russia and the “World of Islam” as natural antagonists that face each other in opposition. In both cases, Orientalists became missionaries, agitating either for Orthodoxy or for atheism. In other words, Soviet atheists took over the position of Orthodox missionaries aiming not at observation but at the “denunciation” (oblichenie) and unmasking (razoblachenie) of Islam in the way pre-Soviet Kazan Orientalists had done. Thus Klimovich defined the goal of his 1929 book, The Contents of the Qur’an, as “to equip anti-religious propagandists with a systematic elementary knowledge of the Qur’an and to expose its inner contradictions.”42 If we replace “anti-religious” by “counter-Muhammadan,” any Orthodox missionary of the 19th and early 20th century would have eagerly supported this goal.

Russian missionaries from the Society for the Restoration of Orthodoxy in the Caucasus considered the Caucasian mountaineers “weakly Islamised” by “Arab and Turkish emissaries” from the Middle East

The Soviet successors of missionary Oriental studies also reproduced the latter’s misleading repertoire of Orientalist notions dating back to colonial times. Terms like “clergy” (dukhovenstvo), “parish” (prikhod), “sectarians” (sektanty) and “holy war” (jihad) were taken from the dictionary of the missionary Orthodox orientology.43 Late Soviet ethnographers were no more scrupulous in borrowing from the vast body of pre-revolutionary missionary works of the “counter-Muhammadan” orientation. An interesting case in point is the textbook on religious anthropology written by Sergei Tokarev: despite his fervent scientific atheism, the author makes numerous Christian Orthodox allusions while explaining Islamic realities. For instance, Tokarev translates the eschatological image of the Mahdi –who, according to a widely held Muslim belief, will rule before the end of the World– as “the Savior.” Furthermore, he attacks the “Muslim clergy” as exploiters and claims that there is “orthodox Islam” and even a “Muslim Church” based on “vakuf property (waqf pious endowments. –V.B.) provided to them by the Caliphate state.”44 The Russian academic school of Islamic studies had rejected these improper missionary notions in the 19th century.

Militant and scientific atheism was not only fundamentally ignorant but also genuinely afraid of Islam. Its adherents were especially fearful of the heterodoxy of popular cults “inspired by religious fanatics” who could not be controlled, and who challenged the “orthodox” Islam supervised by the state. The Orthodox Orientalists had blamed Islam for its “fatalism,” which deterred Muslim believers from social progress. The only difference was that in the Soviet times believers of all confessions were included in the dangerous category of “religious fanatics.”45 Also, militant atheists from the SVB inherited from Orthodox missionaries a number of permanent phobias relating to the alleged Islamic threats to Russia from abroad. Paradoxically, most of these fears appeared to be of foreign origin. Thus, the influence of French Orientalist patterns is reflected in the terminology, especially in a number of “-isms” (“pan-Islamism,” “pan-Turkism,” and similar notions) to which Orthodox missionaries and atheists alike constantly referred. One of these fearful terms was “Muridism,” referring to Sufi networks in the North Caucasus, Central Asia and the Volga region as well as to Muslim resistance to Russia. “Muridism” became the object of study and denunciation in the works of Nikolai Smirnov, Irshad Makatov and various philosophers.46

While Orthodox missionaries had attempted to recover the authentic, original Christian tradition of Russia’s Muslims from under later cultural layers of Islamic “barbarism,” atheistic scholarship had its own way of combating Islam

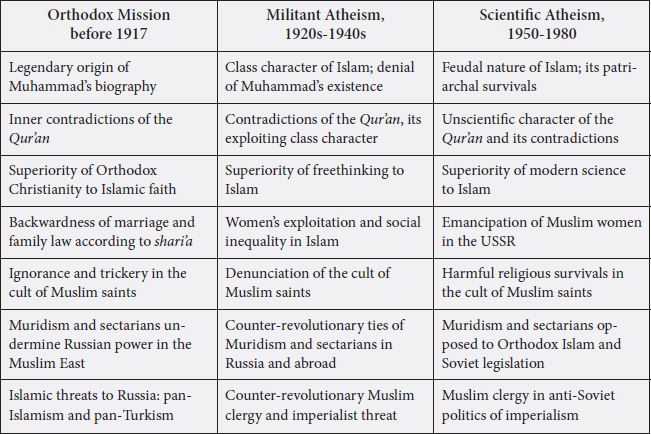

Of course, there were not only continuities but also ruptures between missionary and atheistic “Islamology.” Atheistic criticism of Islam reflected the changed confessional policy under the Soviets. It was also embedded in the general slogans and topoi relating to different periods of socialist building and the Cold War, such as the class character of religion, Islam’s relation to feudal patriarchal survivals, the emancipation of women in the Muslim East, the campaigns for general literacy, the national liberation of the Third World and the global struggle for peace. Christian rhetoric was gradually supplanted by the new Soviet Marxist dictionary. At the same time, new topics and slogans, elaborated by scientific atheists in the late Soviet time, often correlated to concepts that their militant predecessors of the 1920s to 1940s had borrowed from Orthodox missionaries. Graphically these continuities and ruptures can be represented as follows:

Table 1: Main Topics of the Denunciation of Islam in Missionary and Atheistic Scholarship

In their anti-Islamic propaganda, the scientific atheists creatively combined the repertoire of the missionary tradition with the recent findings of Soviet scholarship. A good illustration of this phenomenon is the case of Dagestan, where the medieval Arab conquerors became popular Muslim saints. As is well-known, Russian missionaries from the Society for the Restoration of Orthodoxy in the Caucasus (1860-1917) considered the Caucasian mountaineers “weakly Islamised” by “Arab and Turkish emissaries” from the Middle East. They claimed that the local indigenous tradition was still based on ancient Christianity, which the local population had embraced by the 10th century A.D.; and it was this “authentic” religious tradition that the missionaries hoped to “restore” in the mountains.47 When the atheistic philosopher Irshad Makatov analyzed this interpretation, he painted the image of a greedy Muslim clergy who, as he claimed, deified the Arab conquerors to fleece ignorant believers by collecting their donations at holy places, such as the ziyarats devoted to Shaykh Sulayman and Shalbuz on the top of Shalbuzdag Mountain in Southern Dagestan. To Makatov, the Arab warriors so revered by the benighted Muslims were but cruel foreign conquerors whom the mountaineers had fought against for several centuries, as Soviet historians revealed. Here Makatov referred to the oral traditions of the Arab conquest, presenting the Arabs as a medieval foreign intervention against the freedom and national independence of the mountaineers. Second, Makatov denied the historical existence of Shaykh Sulayman –the person worshiped on the top of Mount Shalbuzdag. He pointed out that the Arabic inscriptions in this holy place (pir) date only from the end of the 18th century, and not from the Arab conquest in the 8th century, nor from “700 years ago” (as the local legend had it). Makatov argued that the cult of Sulayman was based on fables invented by the modern clergy, and that the stories of his alleged miracles should be rejected. Here Makatov referred to Soviet alpinists who had visited Shalbuzdag in 1959 and found nothing miraculous on the top of it.48 This narrative is a good hybrid example of an atheistic lecture dating from 1962. Some details point to the Cold War historical context, such as the attempt to depict Islamization as a foreign intervention against Russia’s territories.

Islam as a Remnant of the Past

While Orthodox missionaries had attempted to recover the authentic, original Christian tradition of Russia’s Muslims from under later cultural layers of Islamic “barbarism,” atheistic scholarship had its own way of combating Islam. The Soviet atheistic discourse regarded Islam as a remnant of the past. In Soviet Russia of the 1920s, religion in general was declared a “remnant of the past” expected to disappear in the future, socialist society. This notion was interpreted in both political and legal terms. All remnants of the old regime were to be destroyed, including religion, which was labeled as a “harmful survival of the past.” In 1928 a special bill “On Crimes that are Remnants of the Tribal Past” was passed in some North Caucasian autonomous Muslim republics of the Russian Socialist Soviet Federation. It became part of the tenth chapter of the Russian Criminal Code in the version of 1926 and was in force until 1996.49 Similar laws were introduced in the criminal codes of some other republics of the Union. This legal basis played a crucial role in the atheistic propaganda of both godless associations. The SVB and the Knowledge Society assisted state and society in overcoming the “harmful influences” of Islam that were “religious survivals” inherited from obsolete, exploitative societies. Their activists were asked to monitor and report all cases when the law on religious organizations was violated. As Nikolai Smirnov put it, “the scholarship of Islam as well as any other religion in our country serves the task to overcome this harmful survival in the mentality and life of the toilers, to propagate a scientific materialist world-view and to provide a communist upbringing for the Soviet people.”50

Muslim citizens of the Soviet Union, praying during an Islamic funeral ceremony. HEINRICH HOFFMANN / ullstein bild via Getty Images

Muslim citizens of the Soviet Union, praying during an Islamic funeral ceremony. HEINRICH HOFFMANN / ullstein bild via Getty Images

The notion of “religious survival,” as used in Soviet atheistic scholarship with reference to Islam, was further elaborated by lawyers, curiously with the help of ethnographers. It is noteworthy (though not often taken into consideration) that the term goes back to positivist anthropologists, mostly to Edward B. Tylor and Lewis H. Morgan; Tylor introduced the notion of “survival” into anthropological usage in the late 19th century; he defined it as “processes, customs, opinions, and so forth, which have been carried on by force of habit into a new state of society different from that in which they had their original home, and they thus remain as proofs and examples of an older constitution of culture out of which a newer has been evolved.”51 Under Soviet rule, Tylor’s works entered the canon of ethnography and history, which was studied and commented upon by each and every Soviet anthropologist –including those from the Muslim borderlands of the country. Taylor’s model was modified in the late Soviet period, and became a generally accepted official cliché. Ethnographers essentialized the concept of “remnant of the past” by relying on the outdated notions of Tylor’s “survival” and that of a “savage society” constructed by Morgan on the example of an idealized 19th century Iroquois society (which never existed in reality).52 Soviet scholars became accustomed to looking for ethnic and national “traditions” and putting them outside history. What is amazing is that after the Second World War, Soviet scholars turned their attention to the already vanished pre-Soviet past while almost completely ignoring the decades of socialist modernization. This perspective determined their approaches to and propaganda against Islam, considered an unchangeable “survival” of foreign origin.

To some extent, the late Soviet atheist and ethnographic scholarship influenced the official discourse of Islam formed in the regional Spiritual Boards of Muslims which were set up in Tashkent, Ufa, Baku and Buynaks (later Makhachkala) in 1943-1944. These institutions worked as a kind of Shari’a Supreme Court system in the regions of their jurisdiction and issued legal opinions (fatwas) in matters of the religious practices of Muslim believers. Like Soviet philosophers and social anthropologists in the 1950s-1980s, the Spiritual Boards permanently banned Sufism and pilgrimage to holy places as “illegal innovations” according to both shari’a prescriptions against bida’ and the Soviet legislation of the religious cults. Their fatwas, addressed to Muslim congregations, condemned these rites as “inadmissible innovations” (bida’) according to the well-known notion of traditional Islamic discourse. The same fatwas, which were translated into Russian for the Soviet supervisors of the Boards, lamented the “ignorance” of ordinary believers and their adherence to the “remnants of the past.”53 In this respect, the Soviet Spiritual Boards appear to be the predecessors of the post-Soviet Salafi critics of “traditional Islam.”54

In post-Soviet Russia, myth-making about Islamic traditions and referring to simplified binary oppositions is characteristic of scholarship and politics alike

Interestingly, at the beginning of the 1960s and 1970s, a number of philosophers specializing in religious studies (scientific atheism) in the autonomous republics of Tatarstan and Dagestan attempted to partly rehabilitate the Islamic past of their peoples. In line with the continuous political revisionism in post-Stalinist academic scholarship, they rethought Islam as a positive and inalienable part of their ethnic cultural heritage and labeled some eminent Muslim scholars of pre-Soviet times “enlighteners” (prosvetiteli) in order to allow academic Orientologists to study their works written in Arabic and old-Tatar in Arabic script, bypassing the Soviet academic censorship. Both attempts succeeded, although this success did not guarantee scholars immunity from ideological attacks at the end of the “stagnation period.” Edward Lazzerini, and later Stéphane A. Dudoignon and Michael Kemper describe these debates about Islamic cultural legacy as ‘Mirasism,’ from Tatar miras ascending to Arabic mirath, heritage, as part of a broader attempt to create a Muslim cultural heritage for different Soviet national communities.55 The movement was headed in Dagestan by Magomed Abdullaev and in Tatarstan by Yahya Abdullin. From their numerous works, we extract a positive image of Islam described in terms of late Soviet Marxist philosophy. It has much in common with general Orientalist premises but is constructed not as “bad” Orient but as “good” Occident. It is progressive, rational, free-thinking, close to working classes and pro-Russian.56

The Russian Discourses on Islam after the Age of Scientific Atheism

The disintegration of the USSR in 1991 was accompanied by a stormy re-Islamisation in the ex-Soviet Muslim regions, including the North Caucasus, Central Asia and the Volga region. The Muslim spiritual elite recovered and even expanded their influence on local societies. They now enjoy the support of former Communist Party officials who have retained their leading positions in the republican governments. Islam has once again become a political trump card, and every politician hastens to assure believers that he loves and protects it. At first glance, the Islamic comeback may seem to be a clean sweep of 70 years of forced secularism and atheistic propaganda. One should, however, take into account that the re-Islamisation emerged in the context of, and in reaction to, the Soviet legacy. Those who claim that an Islamic tradition still persists in the mountains, forget that nowadays in, say, the North Caucasus, about two-thirds of the so-called Muslim mountaineers live in the plains of the country. There is no need to search for a local tradition where it no longer exists. In post-Soviet Russia, myth-making about Islamic traditions and referring to simplified binary oppositions is characteristic of scholarship and politics alike.57

An aerial view shows members of Russia’s Muslim community praying in a street outside Moscow Central Mosque during Eid al-Adha celebrations on September 1, 2017. DMITRY SEREBRYAKOV AFP / Getty Images

An aerial view shows members of Russia’s Muslim community praying in a street outside Moscow Central Mosque during Eid al-Adha celebrations on September 1, 2017. DMITRY SEREBRYAKOV AFP / Getty Images

Today, no one speaks any more of Islam in Russia as a “survival,” at least not officially, nor in scholarship. The Knowledge Society is still working in Russia but without its former atheistic department. Most scientific atheists became scholars of religion (religiovedy) rethought as a positive national legacy. The Institute of Scientific Atheism disappeared in 1991. The Museum of the History of Atheism and Religion in Saint Petersburg changed its name and was expelled from the Kazanskii Cathedral. Houses of Scientific Atheism in Bishkek and Tashkent were closed. The one in Tashkent was transformed into the Republican Center for Propagating Cultural Values in 1991. The Central House of Scientific Atheism in Moscow was abolished in 1991, but was soon returned to the Knowledge Society, and reopened in 1993 as the Central House of Spiritual Heritage (Tsentral’nyi dom dukhovnogo naslediia),58 hosting amateur courses in the Arabic and Turkish languages, in cooperation with the Islamic Cultural Center. University chairs of scientific atheism were transformed into departments of religious studies. Some former denunciators of religion turned into excessive admirers of Islam. For instance, Gasym Kerimov publicly repented his “atheist’s sins” and issued a textbook in which he calls upon Muslims to live according to the shari’a.59

Competing visions of native Islamic tradition emerged in the 1990s. Rival Muslim factions pushed the cause of re-Islamisation in the North Caucasus and other Muslim areas in Russia and the ex-Soviet space: the officially recognized Muslim elite in control of the republican Spiritual Boards appeared in the republican capitals early on, and different groups of religious dissidents –their opponents– united under the derogatory nickname of the “Wahhabi sect.” The factions of traditionalists and Wahhabis or Salafis are bitterly opposed to each other, although in reality the situation is much more diverse. Congregations of Wahhabis emerged at first in the Northern Caucasus. Their imams appealed for the “purification of Islam” from “illicit innovations” (bid’as), such as the Sufi dhikr ritual of remembrance of God, pilgrimage to holy places, celebrations of the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad, recitations of the Qur’an in cemeteries (talqin), and the use of protective charms (sabab) etc. They regarded the Qur’an and the Sunna as the only sources of an authentic Islamic tradition and did not consider their traditionalist opponents faithful Muslims, instead calling them “heathens” (mushrikun). It is interesting to note that the two competing Muslim factions accuse each other of not knowing the authentic, “real” Islam.60 Officially banned in 1999 when the second Russian-Chechen War started, the Wahhabis whose rural centers in the Buynaksk district had been destructed by the Russian federal troops went underground. Nevertheless, their defeat did not mean the reconciliation of competing visions of the custom of the Muslim ‘mountaineers.’

Officially banned in 1999 when the second Russian-Chechen War started, the Wahhabis whose rural centers in the Buynaksk district had been destructed by the Russian federal troops went underground

To some degree, the Soviet atheistic scholarship of Islam prepared the ground for the emergence of this schism in the North Caucasus, with Wahhabis (and partly traditionalists) having borrowed the “scientific” methods that are allegedly based on social progress and recent findings of natural sciences. Even more important, Soviet scientific atheists and contemporary Wahhabi dissidents have much in common. They reduce the doctrine of Islam to the Qur’an and Islamic tradition (al-Sunna), rejecting the long and erudite scholarly tradition of local Muslim scholars as non-Islamic. This can be done easily, because the knowledge of this tradition mostly disappeared under the conditions of anti-religious repression and secularization. Following involuntarily the trajectory of late Soviet atheistic propaganda, Wahhabis denounce the cult of holy places and Sufism as pagan practices introduced to Islam by the ignorant and greedy “Muslim clergy.”61 The very abusive style of such criticism is of Soviet atheistic origin. The Wahhabi discourse also refers to a “remnant of the past:” this is, of course, not Islam, but the alleged pre-Islamic layer still maintained by what they call “ignorant people.”

All this testifies not only to the disappearance of the Soviet atheistic discourse on Islam but, to some degree, continuities in the debates about “wrong” and “true” Islam in the 20th century. Soviet militant and scientific atheism, as well as their predecessor, missionary Orthodox Orientology, have all died, but their cause still influences post-socialist knowledge and politics.

The history of atheistic Islamic studies in the Soviet Union sheds light on the diverse and contradictory character of Orientalism in Russia, which was not a single academic discourse as is usually thought, but rather a bundle of competing and complementary scholarly and political discourses

In conclusion, the history of atheistic Islamic studies in the Soviet Union sheds light on the diverse and contradictory character of Orientalism in Russia, which was not a single academic discourse as is usually thought, but rather a bundle of competing and complementary scholarly and political discourses. One of them investigated Islam in Russia’s own Orient. It reflected the intolerance that dominated Soviet politics, legislation and religious studies, and evolved following oscillations in the relationship between the state and domestic religious communities. Initially, amateur militant atheists conducted anti-Islamic propaganda; after 1959, trained Soviet philosophers called scientific atheists were charged with this project by the state. The Communist party created non-scholarly state-sponsored networks to coordinate atheistic activities throughout the country and direct them: the League of the Militant Godless (1925-1947) that was succeeded by the Knowledge Society (from 1947). The latter inherited funds, property, state clients, forms of anti-religious propaganda, and some contributors of the League, but was built on the foundation of academic institutes and universities, and aimed mostly at the propagation of sciences, not at the eventual eradication of Islam and other confessions as the League had.

I argue that the role of Russian classical Orientology in making Orientalist discourses is exaggerated. Of course, in the field of anti-Islamic propaganda, militant atheists and later Soviet philosophers were indebted to academic Orientologists from the Saint Petersburg-Leningrad school of V.R. Rozen-I.Yu. Krachkovsky as well as to earlier German scholars, upon whose classical translations from Oriental languages and scholarship they relied, while lacking these skills themselves. But the discourse itself was created by non-academic militant atheists and later developed by academic philosophers, and included Islam in the framework of Soviet Marxist rhetoric. Despite its usual anti-tsarist and anti-colonial rhetoric, it often reiterated the claims and outlook of pre-Soviet missionary Orthodox Orientology. So social anthropologists involved in atheistic scholarship as the creators of Soviet anti-Islamic discourse drew considerably on the colonialist and evolutionist premises of 19th century ethnography. In other words, there were continuities between the Orientalist imagination of Islam by pre-Soviet Orthodox missionaries, Soviet militant atheists and post-war philosophers. On the other hand, one can see parallels in the discussions about Islam from the Soviet atheists to the post-Soviet preachers of dissident Islam united under the name of Wahhabis.

Endnotes

- This work was supported by the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS).

- W. Werth, P. Kabytov and A. Miller (eds.), Rossiiskaia Imperiia v Zarubezhnoi Istoriografii. Raboty Poslednikh Let: Antologiia, (Moscow: Novoe Izdatel’stvo, 2005); Michael David-Fox, Peter Holquist and Alexander Martin (eds.), Orientalism and Empire in Russia, (Bloomington: Slavica, 2006).

- David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Russian Orientalism: Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010); Vera Tolz, Russia’s Own Orient: The Politics of Identity and Oriental Studies in the Late Imperial and Early Soviet Periods, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Michael Kemper, Studying Islam in the Soviet Union, (Amsterdam: Vossiuspers UvA, 2009); Michael Kemper and Stephan Conermann (eds.), The Heritage of Soviet Oriental Studies, (London: Routledge, 2011); Philippe Bornet and Svetlana Gorshenina (eds.), L’Orientalisme des Marges: Éclairages à partir de l’Inde et de la Russie, (Lausanne: Université de Lausanne, 2014); Michael Kemper and Artemy M. Kalinovsky (eds.), Reassessing Orientalism: Interlocking Orientologies During the Cold War, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015).

- I will confine the investigation to Islamic studies that directly concern the field of my expertise. From 2002-2007 I examined the Orientalist imagination of Islam in Russia’s Caucasus, and the reception of Said’s concept nowadays. See, Vladimir Bobrovnikov, “Orientalizm – ne Dogma, a Rukovodstvo k Deistviiu? O Perevodakh i Ponimanii Knigi E.W. Saida v Rossii,” in Vladimir Bobrovnikov and S. J. Miri (eds.), Orientalizm vs. Orientalistika, (Moscow: Sadra, 2016), pp. 53-77. I then started a broader project on Soviet atheistic Orientalism in comparison with pre-Soviet Orthodox missionary Orientology. In an article published in 2011, I posed research questions about the continuities and ruptures between them, but can answer them only now. See, Vladamir Bobrovnikov, “The Contribution of Oriental Scholarship to the Soviet Anti-Islamic Discourse: from the Militant Godless to the Knowledge Society,” in Kemper and Conermann (eds.), The Heritage of Soviet Oriental Studies, pp. 66-85.

- The early Soviet pattern of state secularism was much influenced by the French tradition of laicité. It is no coincidence that the first Soviet historical overview on the World History of Atheism drew mostly on French samples: I. Voronitsin, Istoriia Ateizma, 5 Vols, (Moscow: Ateist, 1928-1930), esp. Vols. 2-5.

- Sergei Abashin, “A Prayer for Rain: Practicing Being Soviet and Muslim,” Journal of Islamic Studies,

25, No. 2 (2014), pp. 179-180. - There are no studies of the “Knowledge Society,” and but one solid monograph about the SVB: Daniel Peris, Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998). Peris limited the scope of his investigation to propaganda against the Russian Orthodox Church pp. 4-5, fn. 12.

- Bobrovnikov, “The Contribution of Oriental Scholarship to the Soviet Anti-Islamic Discourse, ” p. 72.

- Religioznye verovaniia narodov, SSSR, (Moscow and Leningrad: State Antireligious Publishers, 1931, Vols. 1-2).

- N. Konovalov, “Soiuz voinstvuiushchikh bezboznnikov,” Voprosy Nauchnogo Ateizma, Vol. 4, (1967), p. 81.

- Edward W. Said, Orientalism, 2nd Edition, (London: Penguin Books, 1995), p. 285.

- Muzei istorii ateizma i religii, (Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1981).

- 60 let Obshchestvu “Znanie:” Prezidenty Obshchestva “Znanie,” (Moscow: Znanie, 2007), pp. 1-2.

- Abashin, “A Prayer for Rain: Practicing Being Soviet and Muslim,” p. 180.

- Micahel Kemper, “Red Orientalism: Mikhail Pavlovich and Marxist in Early Soviet Russia,” Die Welt des Islams, 50, (2010), pp. 445-452, 465-470.

- Leonard Shapiro, The Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 2nd Edition, (New York: Random House, 1970), p. 439; Peris, Storming the Heavens, p. 2.

- Sovetskaia Istoricheskaia Entsiklopediia, Vol. 3 (Moscow: Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia, 1963), p. 816; Bol’shaia Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia, Vol. 9, (Moscow: Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia, 1972), p. 555; Nathaniel Davis, A Long Walk to Church: A Contemporary History of Russian Orthodoxy, (Oxford: Westview Press, 2003), p. 10.

- For more details on the complicated history of MIV and other higher school institutions specialized in Oriental studies in Soviet Russia, see, N. A. Kuznetsova, L. M. Kulagina, Iz istorii sovetskogo vostokovedeniia (Moscow: Nauka, 1970); A. P. Baziiants, Lazarevskii Institut v Istorii Otechestvennogo Vostokovedeniia, (Moscow: Nauka, 1973).

- Beliaev, Proiskhozhdenie islama: khrestomatiia (Moscow: Moskovskii rabochii, 1931); Evgenii Beliaev, “Musul’manskoe Sektanstvo,” in Valentin Ditiakin (ed.), Islam, (Moscow: Ateist, 1931); Nikolai A. Smirnov, Islam i Sovremennyi Vostok, (Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1928); Nikolai A. Smirnov, Sovremennyi Islam (the second revised and extended edition of his monograph: Islam i Sovremennyi Vostok, (Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1930); Nikolai A. Simirnov, Chadra: proiskhozhdenie pokryvala musul’manskoi zhenshchiny i bor’ba s nim, (Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1929); Nikolai A. Smirnov, Musul’manskoe sektantstvo (Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1930); Nikolai. A. Smirnov, Islam i ego Klassovaia Rol, (Moscow and Leningrad: GIZ, 1930). For details of the biographies of Beliaev and Smirnov see, Aziia i Afrika Segodnia Vol. 10, (1965), pp. 261-262; V. I. Koretskii, “K Semidesiatiletiiu Nikolaia Aleksandrovicha Smirnova,” Voprosy istorii, Vol. 5, (1967), pp. 170-171.

- V. Vasil’kov and M. Iu. Sorokina (eds.), Liudi i sud’by. Biobibliograficheskii slovar’ Vostokovedov – Zhertv Politicheskogo Terrora v Sovetskii Period (1917-1991), (St. Petersburg: Peterburgskoe vostokovedenie, 2003), pp. 42-43.

- Vasil’kov and Sorokina (eds.), Liudi i sud’by. Biobibliograficheskii slovar’ Vostokovedov, 107, 362-364. Cf. S. D. Miliband, Vostokovedy Rossii XX – Nachalo XXI Veka Biobibliograficheskii Slovar, 2 Vols, (Moscow: Vostochnaia Literatura, 2008), Vol. 1, pp. 63, 283.

- Miliband, Vostokovedy Rossii XX – Nachalo XXI Veka. Biobibliograficheskii Slovar, 283.

- M. Reshetov, “Tragediia Lichnosti: Nikolai Mikhailovich Matorin,” in D. D. Tumarkin (ed.), Repressirovannye Etnografy, (Moscow: Vostochnaia Literatura, 2003), pp. 147-192. Matorin continued his anti-religious studies even when he was detained in a concentration camp near Tashkent. Before his execution in 1936, he wrote the Program for Gathering Materials on Religious Beliefs and Cult in Everyday Islam. See, Vasil’kov and Sorokina (eds.), Liudi i Sud’by, p. 259.

- Miliband, Biobibliograficheskii Slovar, 255; Michael Kemper, “Ljucian Klimovič: Der Ideologische Bluthund der Sowjetischen Islamkunde und Zentralasienliteratur,” Asiatische Studien – Etudes Asiatiques, Vol. 63, No. 2 (2009), p. 95.

- Vasil’kov and Sorokina, Liudi i Sud’by, p. 376; Kemper, “The Soviet Discourse,” pp. 25-28.

- D. Ashnin, V. N. Alpatov and D. M. Nasilov, Repressirovannaia Tiurkologiia, (Moscow: Vostochnaia Literatura, 2002), p. 20.

- See for instance, the CVs of Soviet Orientalists in S. D. Miliband’s Biobibliograficheskii Slovar’ Sovetskikh Vostokovedov, (Moscow: Glavnaia Redaktsiia Vostochnoi Literatury, 1973), p. 43: A. M. Arsharuni, pp. 72-73: Evgenii Beliaev, p. 124: Hadzhi Gabidullin, p. 255: Liutsian Klimovich, and p. 515: Nikolai. A. Smirnov, more informative in this respect are the two later editions of Miliband’s dictionary which appeared in 1995 and 2008.

- Both of them changed the field of study. Klimovich turned to the Soviet literature in Oriental languages and Ditiakin to the history of freethinking in Renaissance Europe. See, V. T. Ditiakin,

Leonardo da Vinci, (Moscow: Znanie, 1952); L. I. Klimovich, Znanie Pobezhdaet (Nekotorye Voprosy

Kritiki Islama), (Moscow: Znanie, 1967); Znanie Pobezhdaet, Pisateli Vostoka ob Islame, (Moscow: Znanie, 1978). - See, I. Makatov, Kul’t sviatykh – Perezhitok Proshlogo, (Makhachkala: Dagknigoizdat, 1962); M. V. Vagabov, Otnoshenie Musul’manskoi Religii k Zhenshchine, (Moscow: Znanie, 1962); M. A. Abdullaev and S. M. Gadzhiev, Pogovorim o Musul’manskoi Religii, (Makhachkala: Dagknigoizdat, 1962); S. M. Gadzhiev, Puti preodoleniia ideologii islama, (Makhachkala: Dagknigoizdat, 1963); M. A. Abdullaev, Ocherki nauchnogo ateizma, (Makhachkala: Dagknigoizdat, 1972); I. Makatov, Islam, Veruiushchii, Sovremennost, (Makhachkala: Dagknigoizdat, 1974); M. A. Abdullaev and M.bV. Vagabov, Aktual’nye Problemy Kritiki i Preodoleniia Islama, (Makhachkala: Dagknigoizdat, 1975); Iu. G. Petrash, Islom, Fan, Koinet, (Tashkent: Fan, 1976); V. Iu. Gadaev, Dorogoi Istiny, (Grozny: Checheno-Ingushskoe Knizhnoe Izdatel’stvo, 1982).

- See, L. R. Gordon-Polonskaia, Musulmanskie Techeniia v Obshchestvennoi Mysli Indii i Pakistana, (Kritika Musulmanskogo Natsionalizma), (Moscow: Nauka, 1963).

- See the entries, Alexander Alexandrovich Semenov and Mikhail Meerovich Tsvibak in Vasil’kov and Sorokina (eds.), Liudi i Sud’by.

- See memories of the poet and translator Vasilii Benaki who had been trained in Iranian studies at the Oriental Faculty in post Second World War Leningrad and witnessed Klimovich’s attack on academic Orientalists in 1949: Vasilii Betaki, “Snova-Casanova,” Mosty, 3-8 (2004), Chapter 11 retrieved from http://bolvan.ph.utexas.edu/~vadim/betaki/memuary/V11.html.

- Klimovich, Prazdniki i Posty Islama, (Moscow: State Antireligious Publishers, 1941), pp. 15-16.

- Nikolai A. Smirnov, Ocherki Istorii Izucheniia Islama v SSSR, (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1954), p. 122; Cf. E. Beliaev, “Bibliografiia po Islamu na Russkom Iazyke (Dorevolutsionnye Izdaniia),” in Islam: Sbornik Statei, (Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1931), p. 133; Beliaev (ed.), Proiskhozhdenie Islama, p. 9; S. A. Tokarev, Religiia v Istorii Narodov Mira, (Moscow: Politizdat, 1963), Chapter 24.

- Beliaev, “Bibliografiia po Islamu na Russkom Iazyke,” pp. 149-155.

- Smirnov, Ocherki Istorii Izucheniia Islama v SSSR, p. 82.

- Smirnov, Ocherki Istorii Izucheniia Islama v SSSR, p. 166.

- Bogoliubovskii, Islam, ego Proiskhozhdenie i Sushchnost’ po Sravneniiu s Khristianstvom, (Samara, 1885); Ya. Koblov, Antropologiia Korana v Sravnenii s Khistianskim Ucheniem o Cheloveke, (Kazan, 1905).

- Klimovich, Soderzhanie Korana, (Moscow: Atheist, 1930), pp. 91-96.

- Beliaev (ed.), Proiskhozhdenie islama: khrestomatiia, pp. 9-10.

- See, Tokarev, Religiia v Istorii Narodov Mira; L. I. Klimovich, Kniga o Korane, (Moscow: Politizdat, 1986).

- M. Arsharuni, “Bibliografiia po Islamu,” in Ditiakin (ed.), Islam, (Moscow: Bezbozhnik, 1931), p. 158.

- See, Smirnov, Musul’manskoe Sektantstvo; Abdullaev and Gadzhiev, Pogovorim o Musul’manskoi Religii; Abdullaev (ed.), Ocherki Nauchnogo Ateizma; Makatov, Islam, Veruiushchii, Sovremennost’;

Tokarev, Religiia v Istorii Narodov Mira, passim. - Tokarev, Religiia v Istorii Narodov Mira, passim, especially Chapter 24.

- the treatment of God’s predestination (al-qadar) in V. Cherevanskii, Mir Islama i ego Probuzhdenie, (St. Petersburg, 1901), part 1, p. 320; and in S. D. Skazkin (ed.), Nastol’naia Kniga Ateista, (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Politicheskoi Literatury, 1971), pp. 203, 241.

- Vladimir Bobrovnikov and Michael Kemper, “Muridism in Russia and the Soviet Union,” in Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas and Everett Rowson (eds.), Encyclopedia of Islam, 3rd Edition, (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

- Austin Jersild, Orientalism and Empire: North Caucasus Mountain Peoples and the Georgian Frontier, 1845-1917, (London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002), pp. 42-47.

- Makatov, Kul’t sviatykh - Perezhitok Proshlogo, pp. 5, 9-10.

- Vladimir Bobrovnikov, “Obychai kak Iuridicheskaia Fiktsiia: Traditsionnyi Islam v Religioznom Zakonodatel’stve Postsovetskogo Dagestana,” Gumanitarnaia Mysl’ Iuga Rossii, No. 1 (2006), p. 5.

- Smirnov, Ocherki Istorii Izucheniia Islama v SSSR, (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1954), p. 142.

- Edward Burnett Tylor, Primitive Culture: Researches in the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom, 3rd Edition, Vol. 1, (New York: Henry Holt, 1889), p. 16.

- For more details see, Vladimir Bobrovnikov, “From Collective Farm to Islamic Museum? Deconstructing the Narrative of Highlanders’ Traditions in Daghestan,” in Florian Mühlfried and Sergey Sokolovskiy (eds.), Exploring the Edge of Empire: Soviet Era Anthropology in the Caucasus and Central Asia, (Zürich, Berlin: Lit-Verlag, 2011), pp. 107-108, 111; Devin A. DeWeese, “Survival Strategies: Reflections on the Notion of Religious ‘Survivals’ in Soviet Ethnographic Studies of Muslim Religious Life in Central Asia,” Exploring the Edge of Empire: Soviet Era Anthropology in the Caucasus and Central Asia, (Zürich, Berlin: Lit-Verlag, 2011), pp. 35-58.

- Michael Kemper and Shamil Shikhaliev, “Two Soviet Fatwas from the North Caucasus,” in Alfrid K. Bustanov and Michael Kemper (eds.), Islamic Authority and the Russian Language: Studies on Texts from European Russia, the North Caucasus and West Siberia, (Amsterdam: Pegasus, 2012), pp. 55-102.

- Eren Tasar, “The Official Madrasas of Soviet Uzbekistan,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 59, (2016), pp. 265-302; Eren Tasar, Soviet and Muslim: The Institutionalization of Islam in Central Asia, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 150-161, 368-369.

- Edward J. Lazzerini, “Tatarovedenie and the ‘New Historiography’ in the Soviet Union: Revising the Interpretation of the Tatar-Russian Relationship,” Slavic Review, 40, No. 4 (1981), pp. 625-635; S. A. Dudoignon, “Djadidisme, Mirasisme, Islamisme,” Cahiers du Monde Russe, Vol. 37, No 1-2 (1996), pp. 12-40; Michael Kemper, “Ijtihad into Philosophy: Islam as Cultural Heritage in post-Stalinist Daghestan,” Central Asian Survey, Vol. 30, No. 1 (2014), pp. 53-80.

- Kemper, “Ijtihad into Philosophy,” pp. 69-70.

- Michael Kemper, Alfrid K. Bustanov (eds.), Islamic Authority and the Russian Language: Studies on Texts from European Russia, the North Caucasus and West Siberia, (Amsterdam: Pegasus, 2012), pp. 15-19.

- See the website of the Knowledge Society at: http://www.znanie.org/docs/DDN.html.

- M. Kerimov, Shariat – Zakon Zhizni Musul’man, (Moscow: RAGS, 2008). Cf. a critical analysis of the shari’a justice by the same author from the late Soviet atheistic perspective: G. M. Kerimov, Shariat i ego Sotsal’naia Sushchnost, (Moscow: Glavnaia Redaktsiia Vostochnoi Literatury Izdatel’stva Nauka, 1978).

- Vladimir Bobrovnikov, “Post-Socialist Forms of Islam: North Caucasian Wahhabis,” ISIM Newsletter, 7 (2001), p. 29.

- See, for instance, Baha’ al-din Muhammad, Namaz, (Moscow: Sanlada, 1994), pp. 5-8. For a more detailed discussion of this question, see: Bobrovnikov, “Post-Socialist Forms of Islam,” p. 29; Vladimir Bobrovnikov, Musul’mane Severnogo Kavkaza: Obychai, Pravo, Nasilie, (Moscow: Vostochnaia Literatura, 2002), pp. 262-281.