Introduction

Mounting tension between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the occupied Nagorno-Karabakh region and seven adjacent districts of Azerbaijan turned into a full-scale war on September 27, 2020. As a result of the six-week-long Second Karabakh war, the Azerbaijani army liberated considerable parts of its occupied territories including Shusha city, considered a cradle of Azerbaijani culture.

Following the liberation of Shusha, the Armenian leadership had little choice but to accept a deal brokered by Moscow. The deal enabled Azerbaijan to retain positions liberated since the beginning of the war and forced Armenia to withdraw from districts surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh that they had controlled for at least 26 years. The trilateral deal also stated the restoration of the blocked transit corridors between the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic –an exclave of Azerbaijan– and mainland Azerbaijan, between Armenia and Russia, and between Armenia and Iran. Correspondingly, the planned corridor will connect Turkey with Russia, as well as establishing an alternative route between Europe and Asia.

The Second Karabakh war also drew the attention of the international community to the protracted conflict. Shortly after the break out of violence, almost all major powers, international organizations, and neighboring countries called for the fighting parties to de-escalate the tension and engage in peaceful negotiations.

The EU and the member-states were also among the forerunners of peace calls. Taking into account the EU’s norm driven foreign policy and commitment to international law, it was expected that through their issued statements both Brussels and member-states would step up in support of Azerbaijan, which had de facto lost control over one-fifth of its internationally recognized territory, and 700,000 Azerbaijani Internally Displaced People (IDPs) that for three decades had been deprived of their natural right to return to their homes.

However, the EU adhered to its low profile and neutral stance in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and contented with statements calling the conflicting parties to observe an immediate ceasefire and political dialogue. Nevertheless, the stance of France –one of the founding states of the EU, the architect of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), the forerunner of further integration in EU, and the only representative of the EU in the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group mandated to mediate the conflict resolution– was of a different nature which puts its credibility as an impartial mediator at stake.

This commentary examines the stance of Paris in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and analyzes whether the stance corresponds with the EU interests and values. To answer the given question, the paper studies the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict from the context of international law, the post-ceasefire period 1994-2020, the EU treaties, policy strategies, the final declarations of the Eastern Partnership summits, the resolutions of the European Parliament, and statements of the EU officials, and contrasts them with the standpoint of France.

Nagorno-Karabakh: A Revival of Conflict

The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region is one of the most complicated conflicts inherited from the Soviet Union. Encouraged by the Glasnost policy of Mikhail Gorbachev, the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) in the late 1980s organized petitions in the Nagorno-Karabakh Oblast of Azerbaijan SSR, predominantly populated by Armenians, for its unification with the Armenian SSR, thus laying the seeds of separatist demands in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Even though, in compliance with the principle of inviolability of borders, the Soviet Politburo formally rejected the transfer of Nagorno-Karabakh from the Azerbaijani SSR to the Armenian SSR, in practice, as part of its imperial divide and rule policy Moscow kept inactive and turned a blind eye to the attempts to incorporate Nagorno-Karabakh into Armenia.1

The early 1990s were years of political turmoil in Azerbaijan, and Armenia skillfully exploited the power vacuum in the internal governance of Azerbaijan by occupying Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent districts

Further to its illegitimate annexation demands, Armenia backed separatist groups in the Nagorno-Karabakh region with arms and supplies.2 However, the dissolution of the Soviet Union forced Armenia to switch its demands from annexation to the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh, so as not to be labelled as an aggressor state defying the Westphalian system and international law.3

The dissolution of the Soviet Union also exposed the stance of Russia to the conflict. With the aim to retain all three South Caucasian countries in its orbit, incorporate Azerbaijan into the Soviet Union’s successor organization Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), prevent the reinforcement of Turkish influence in the Caucasus, and ensure Azerbaijan’s oil export via Russian soil, Kremlin politically and militarily backed Armenia.4

The early 1990s were years of political turmoil in Azerbaijan, and Armenia skillfully exploited the power vacuum in the internal governance of Azerbaijan by occupying Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent districts. As a result, 700,000 Azerbaijanis were expelled from their lands, and one-fifth of Azerbaijani territories were occupied by Armenia. In response to ethnic cleansing and occupation of one-fifth of Azerbaijani territories, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed four resolutions –822, 853, 874, 884– demanding the unconditional and immediate withdrawal of Armenian military forces and supporting the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan.

Notwithstanding the unilateral endeavors to mediate, the conflict did not attract the attention of the international community as a whole after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Only in 1992, alerted by the violence and death toll, the international community decided to intervene.

The meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki in March 1992 agreed that the CSCE must play a key role in the peaceful resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan and decided to call a conference in Minsk with the participation of Armenia and Azerbaijan, and other CSCE member-states.

However, the efforts of the Minsk Group did not bear its fruits immediately. Finally in 1994, with Moscow’s mediation, Armenia and Azerbaijan concluded the ceasefire agreement and agreed to resolve the conflict by pursuing peace negotiations led by the OSCE Minsk Group. In 1996 the OSCE rearranged the Minsk Group and established a permanent troika co-chairmanship institute comprised of the Russian Federation, France, and the U.S.

Armenia’s Velvet Revolution and subsequent democratic elections were perceived as an opportunity and impetus for a peaceful settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan

The OSCE Minsk Group throughout the negotiations came out with ‘step-by-step,’ ‘package,’ ‘common state,’ ‘land exchange’ peaceful settlement proposals. These road maps were either rejected by both sides or accepted only by one side.5

In 2007, the Minsk Group at the OSCE Ministerial Conference in Madrid came up with a new proposal, later to be called Madrid Principles or Basic Principles.6 The Basic Principles embraced both territorial integrity and the right for self-determination principles, and thus, Minsk Group mediators asserted that the proposal addresses the demands of both sides. In 2009, the presidents of three co-chair countries –Russia, France, and the U.S.– attending the G8 Summit released a joint statement calling Armenia and Azerbaijan to finalize the peace agreement in accordance with the Madrid Principles.7

The negotiations based on Madrid Principles accelerated in 2008 with the unilateral mediation effort of Russian President Medvedev. In less than 2 years, President Medvedev arranged 10 meetings between Azerbaijani and Armenian presidents. It was believed that the intensive round of talks between the presidents would result in the conclusion of a deal on Madrid Principles in the Kazan meeting held in June 2011.8

However, like previous settlement proposals, the negotiations over the Madrid Principles did not come to fruition. Some political analysts explained this failure as a result of Armenia’s discontent over one of the elements that envisaged the withdrawal of its troops from the occupied 7 districts before determining the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh.9

Armenia’s reluctance to engage in result-oriented negotiations, so aiming to prolong the occupation and attempts to halt the process by provocations along the Line of Contact (LoC) resulted in the Four-Day war in April 2016. The Four-Day war enabled Azerbaijan to liberate strategically important heights. Moreover, Azerbaijan in words and deeds demonstrated that it will not take part in negotiations for the sake of negotiations.

This defeat and ill-governance led to the uprise and overthrow of the regime in Armenia in 2018.10 Armenia’s Velvet Revolution and subsequent democratic elections were perceived as an opportunity and impetus for a peaceful settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan.11

However, any hopes of Azerbaijan in the democratically elected Prime Minister of Armenia, Nikol Pashinyan, were soon dashed. In the aftermath of his election, Pashinyan attempted to change the format of talks, which was turned down by both Azerbaijan and the Minsk Group.12

On March 29, 2019, the Minister of Defense David Tonoyan in his meeting with American Armenians rejected the “territories-for-peace” proposal of Azerbaijan and instead alluded to Armenia’s readiness to launch a new war for new territories.13 The bellicose rhetoric was also continued by Armenia’s Prime Minister Pashinyan. The visit of Pashinyan to the occupied territories in August 2019, and his nationalistic ‘unification’ (Miatsum in Armenian) and “Nagorno-Karabakh is Armenia” chants in front of the masses in the capital city of the so-called “Nagorno-Karabakh Republic” hampered the negotiating process.14

Moreover, in July 2019 the Armenian government announced its decision to build a 150 km-long road to connect Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh, which would pass through the occupied Azerbaijani districts of Gubadli and Jabrayil.15

The deliberate steps of Armenia to halt the peace process, and thus to prolong the occupation, reached its peak in July 2020 with violation of the ceasefire on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. The clashes occurred in Tovuz province, which plays a crucial role as a hub for the critical energy and transportation infrastructure of Azerbaijan, connecting the Caspian Sea with Europe.16

Further to its military provocations, Armenia announced the settlement in Nagorno-Karabakh of Lebanese Armenian families who had suffered as a result of the explosion at the Beirut port on August 4, 2020. The illegal settlement of Lebanese Armenians, for the purpose of changing the ethnic map in the occupied territories, caused fury in Baku and completely disrupted any prospect of a peaceful settlement process.17

The EU Stance on the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

The settlement of ethno-territorial conflicts beyond its borders is one of the key foreign policy priorities of the EU. Owing to the fact that the EU itself was born as a result of the long-term conflict prevention policy, the mechanisms adopted by the EU in the resolution of the conflicts rests on the domestic norms and values of the Union itself. These norms and values have been clearly indicated in the treaties –Treaty on European Union (TEU) and Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)– of the EU as follows:

The Union’s action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.18

Armenia’s Velvet Revolution and subsequent democratic elections were perceived as an opportunity and impetus for a peaceful settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan

The Union shall define and pursue common policies and actions, and shall work for a high degree of cooperation in all fields of international relations, in order to:

(c) preserve peace, prevent conflicts and strengthen international security, in accordance with the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter, with the principles of the Helsinki Final Act and with the aims of the Charter of Paris, including those relating to external borders.19

Even though the treaties also retain the sovereignty of the individual member-states in foreign policy, the TEU obliges the member-states to support the CFSP and to refrain from any political act contrary to the interests of the Union.

The Member States shall support the Union’s external and security policy actively and unreservedly in a spirit of loyalty and mutual solidarity and shall comply with the Union’s action in this area.

The Member States shall work together to enhance and develop their mutual political solidarity. They shall refrain from any action which is contrary to the interests of the Union or likely to impair its effectiveness as a cohesive force in international relations.20

In addition to foreign policy norms mentioned in the treaties, the EU communicated additional international norm-driven approaches, ‘A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy,’ with respect to territorial disputes. These policy norms were developed to be projected by the actorness of the EU in the resolution of conflicts:

The sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of states, the inviolability of borders, and the peaceful settlement of disputes are key elements of the European security order. These principles apply to all states, both within and beyond the EU’s borders.21

The above-mentioned policy norms have been substantially translated to the actorness of the EU in the settlement of conflicts. Apart from the Kosovo case and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which are considered sui generis cases, the EU resists the demands for secession or two-state solution models. Instead, the EU advocates either a power-sharing model or integration of minority groups within a unitary state.

The power-sharing model embraces the federative model of governance, and thus, meets both territorial integrity and rights of self-determination. This model is also the most favored solution of the EU for the conflicts of the post-Soviet space. The latter model envisages the extension of the individual, cultural, and minority rights within a unitary state, and excludes political decentralization. This model is typical for the EU stance on Turkey’s Kurdish question. 22

At the outset, the stance of the EU in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was ambiguous. Surprisingly this ambiguity was introduced with the conclusion of European Neighborhood Policy Action Plans (ENP AP) with both Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2006, where the EU failed to take the responsibility of a new security actor in the region.

While the ENP AP concluded between the EU and Azerbaijan supported the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, based on the resolutions of the UNSC that endorse territorial integrity of Azerbaijan, the ENP AP concluded between EU and Armenia stated the support of the EU to the self-determination right of Nagorno-Karabakh.23 The ambiguity and uncertainty of the EU were mainly due to the reluctance and fear of member-states to antagonize Moscow in its backyard.

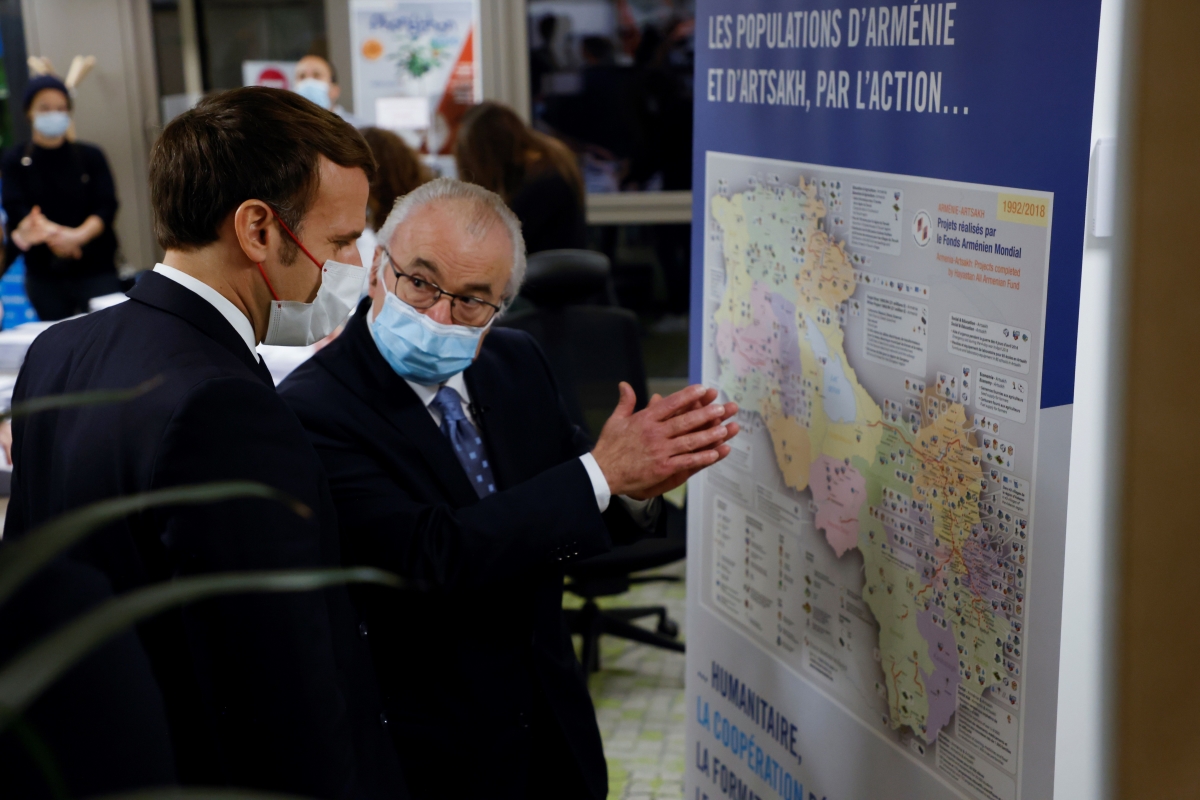

French President Emmanuel Macron (L) listens to the President of the Armenian Funds of France, Pierre Terzian (R), as he visits the 2020 Phoneton, on November 21, 2020, in Paris. LUDOVIC MARIN / POOL / AFP via Getty Images

French President Emmanuel Macron (L) listens to the President of the Armenian Funds of France, Pierre Terzian (R), as he visits the 2020 Phoneton, on November 21, 2020, in Paris. LUDOVIC MARIN / POOL / AFP via Getty Images

The ambiguous stance of the EU on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue caused a serious rift between Baku and Brussels. Dissatisfied with the EU’s unclear stance on the issue of territorial integrity, Baku in 2013 refused to carry out negotiations on the Association Agreement.24 Baku’s discontent became very evident in the EU-Eastern Partnership (EaP) Summit held in Riga, where President Aliyev refused to take part and Azerbaijan declined to sign the joint declaration of the summit. Baku’s objection was due to the firm stance of the EU on the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia compared to its failure to take a similar stance on Nagorno-Karabakh.25

Nevertheless, the EU took into account the complaints of Baku and brought more clarity to its stance on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In this regard, the EaP Brussels Summit in 2017 was a breakthrough. Despite the protests and attempts of Armenia to block the Joint Declaration, the EU included the paragraph expressing the support to the territorial integrity of all EaP countries.26 The support for the territorial integrity issue was welcomed with satisfaction by President Ilham Aliyev: “Final Declaration adopted at the Eastern Partnership Summit of the European Union supported the territorial integrity of member countries, which is Azerbaijan’s diplomatic achievement.”27

The support of the EU to territorial integrity was reiterated in the visit of the European Council President Donald Tusk to Baku and Yerevan in July 2019.

The deliberate steps of Armenia to halt the peace process, and thus to prolong the occupation, reached its peak in July 2020 with violation of the ceasefire on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border

The EU supports Azerbaijan’s sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity.28

The conflict [Nagorno-Karabakh] does not have a military solution and needs a political settlement in accordance with international law and principles. The EU continues to fully support the efforts of the Minsk Group Co-Chairs and their focus on a fair and lasting settlement based on the core principles of the Helsinki Final Act.29

Consistency in EU endorsement to Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity followed in 2020 as well. On May 11, 2020, the Foreign Ministers of member states approved the conclusions on the Eastern Partnership policy beyond 2020 which reaffirmed the commitment of the EU to the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The Council reaffirms the joint commitment to building a common area of shared democracy, prosperity, and stability. It is anchored in our shared commitment to a rules based international order, international law, including territorial integrity, independence, and sovereignty, as also stated in the principles of the Helsinki Final Act and the OSCE Charter of Paris, as well as fundamental values.30

The position of the Council stated in the Eastern Partnership policy beyond 2020 was restated by the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell at the UN Security Council on May 28, 2020. In his remarks on the EU’s role in international security, Borrell said that “the support for territorial integrity and sovereignty of Eastern partners will remain the key elements of the EU’s relations with these countries.”31

The identical position was put by the European Parliament under the resolution 2019/2209 (INI). The resolution condemned the violation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the EaP countries, reiterated the commitment of the EU not to recognize forcible changes in the borders of EaP countries. Moreover, the resolution restates the commitment of the EU to the peaceful settlement of conflicts in accordance with the norms and principles of international law, the UN Charter, and the Helsinki Final Act.32

Further to the EU’s general approach to settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the EU has also reacted to the specific developments hindering the peaceful settlement process. On June 9, 2020, the standing rapporteurs of the European Parliament on Armenia and Azerbaijan issued a joint statement on the construction of a new highway between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. The joint statement condemned the decision of Armenia to build a new highway to Nagorno-Karabakh without the consent of Azerbaijan and called it a violation of international law. In addition, the statement expressed the anxiety that the construction could anchor the illegal occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding districts.33

Notwithstanding, the unequivocal state-centric stance towards the territorial conflicts expressed in the treaties and policy strategies, the Union has not invoked its active engagement in the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In the absence of coherent strategy, tools, and internal coordination, the member-states pursue their parallel foreign policy which undermines the CFSP and prevents the Union to materialize its single voice in times of escalating tensions.

French Reversal: From Neutrality to Partiality and Biased Stance

The acquisition of the role as co-chair by France at the OSCE Minsk Group dates back to 1997. In fact, France along with Russia had been nominated to co-chair the Minsk Group at the Lisbon Summit of the OSCE held in December 1996. However, Azerbaijan opposed the nomination of France stating that due to the large and influential Armenian community of France, Azerbaijan cannot consider it as an impartial mediator. As a substitute for the French nomination, Azerbaijan nominated the U.S. Nevertheless, in February 1997 the parties reached a compromise and agreed to set up a co-chairmanship institute based on Russia, France, and the U.S.34

Notwithstanding, the unequivocal state-centric stance towards the territorial conflicts expressed in the treaties and policy strategies, the Union has not invoked its active engagement in the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

Despite the apparent rift among the troika countries on almost every international issue, in 23 years of mediation practice, they enjoyed surprising harmony in the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. While in theory, they recognized the occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding districts by Armenia, in practice, they failed to hold Armenia accountable for its occupation and change the status quo. Nonetheless, thanks to its consistent diplomatic efforts Azerbaijan in recent years has improved political and economic ties with all three Minsk Group co-chair countries, and thus, accomplished a slight balance and neutrality in their stance. Azerbaijan has paid particular importance to the improvement of its relationship with France because it hosts the biggest Armenian diaspora, 400,000 to 600,000, in Europe and the third-biggest in the world. Therefore, the Armenian community has always enjoyed influence over the shaping of French foreign policy toward the South Caucasus and Turkey.

Furthermore, the involvement of French energy giant TOTAL in the exploration and production of hydrocarbon resources in the Caspian basin was an important step to countervail the influence of pro-Armenia lobby groups against Azerbaijan. In addition to the cooperation in the energy field, Azerbaijan strengthened its political and economic ties with France by increasing up to 65, the number of French companies operating in various sectors of the Azerbaijan economy. 35

Moreover, to confine the Armenian lobby and secure French impartiality in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict Baku even expressed its readiness to consider its participation in peacekeeping operations in the Sahel region.36

However, the bid of Azerbaijan to sustain the impartiality of France in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict did not prevail. France’s stance in favor of Armenia, thus in violation of the mediator’s commitment to neutrality, has become quite apparent following the escalation of tension on September 27, 2020, that resulted in the Second Karabakh war.

France’s stance in favor of Armenia, thus in violation of the mediator’s commitment to neutrality, has become quite apparent following the escalation of tension on September 27, 2020, that resulted in the Second Karabakh war

On September 30, 2020, the President of France Emmanuel Macron accused Turkey of its ‘warlike‘ rhetoric on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict for encouraging Azerbaijan to ‘reconquer’ Nagorno-Karabakh.37 The stance of Macron was slammed by Azerbaijani officials saying that the statement is biased and not in compliance with international law. Yet, a few days later President Macron went further, claiming that Turkey deployed more than 300 Syrian jihadist fighters to Azerbaijan.38 The accusations towards Azerbaijan and Turkey caused fury both in Baku and Ankara, and President Aliyev in his interview demanded proof or an apology for the groundless allegations and responsible behavior from his French counterpart.39

Bearing in mind that France, together with Russia and the U.S., is one of the three co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group mandated to mediate the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the reckless statement has undermined its role as an impartial mediator. Speaking to Al Jazeera on the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, President Aliyev called all co-chair countries to act in the capacity of the mediator and adhere to an impartial position or to step down from the Minsk Group co-chairmanship.40

Following the wave of criticisms from Baku, Paris had to re-adopt a neutral stance. Talking to Le Figaro the Foreign Minister of France, Jean-Yves Le Drian, said that he had pressed the political leadership to adopt a neutral stance towards the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. According to Le Drian due to its rich hydrocarbon resources, Azerbaijan is of particular importance for international energy companies. Nonetheless, he admitted the affinity with Armenia, and thus, urged his government to remain neutral. 41

The shift in France’s stance towards neutrality was welcomed in Baku. President Aliyev in his interview with France 24 expressed his satisfaction with the neutrality of President Macron and characterized the latest approach of the French President as ‘very positive.’42 In his tweet, the Ambassador of France to Baku Zacharie Gross also confirmed that the troubled bilateral relations were fixed.43

The deliberate actions of France, which have not only deteriorated the relations with Azerbaijan but also violated the basic principles of international law, can’t be explained entirely by the influence of the Armenian diaspora

However, the hopes that soured relations between France and Azerbaijan would be put back on track in the interest of French energy companies operating in Azerbaijan, and also the political commitment of a mediator state to maintain neutrality between the conflicting parties were once more undermined. A day after the optimistic tweet of the French Ambassador, the UN Security Council held a discussion on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict that envisaged the adoption of a statement on behalf of the President of the UNSC. The statement drafted mainly by Russia and France did not refer to the four resolutions of the UNSC on the conflict, and therefore, met with anger in Baku. Fortunately, the statement was withdrawn following the objections of the non-permanent members of the UNSC.44

The inconsistent stance of France with international law was also followed in its comments on the liberation of Shusha, and later the truce agreement brokered by Russia. Commenting on the statements of the French President and Foreign Minister, Azerbaijani presidential aide Hikmat Hajiyev said that “France attempts to be more Armenian than the Armenians themselves.”45

The final straw in France’s biased stance became an adoption of a resolution by the French Senate entitled “On the need to recognize Nagorno-Karabakh.” Although the French Secretary of State at the Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs, Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, in response to the non-binding resolution noted that “unilateral recognition of Karabakh will do no good for anyone,”46 the endorsement of the bill by Macron’s party –Republic on the Move– has been perceived as an apparent display of hypocrisy in Baku.

The deliberate actions of France, which have not only deteriorated the relations with Azerbaijan but also violated the basic principles of international law, can’t be explained entirely by the influence of the Armenian diaspora. Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan was another strong motive for France to side with Armenia. Scrambling with Turkey over the Eastern Mediterranean and Libya, France backed Armenia to forestall the strengthened security presence of Turkey in the South Caucasus.47

The aforementioned incidents have not irreversibly but seriously undermined the trust of Baku in Paris. Yet, it has not only endangered the relations between France and Azerbaijan but also the faith of Azerbaijan in the EU. As a member-state France is the only representative of the EU in the Minsk Group, and thus, is also supposed to mediate the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in accordance with the interests and values of the EU.

Conclusion

The paper has examined the stance of France in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict with the central argument that the stance of France does not comply with EU norms and interests. Notwithstanding the low-profile actorness, lack of coherent strategy, tools, and internal coordination in the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the EU in theory and practice upholds the principle of territorial integrity in the settlement process. The support of the EU to territorial integrity is provided on normative and interest-based grounds and has been clearly accommodated in the EU treaties, final declarations of the EaP summits, resolutions of the European Parliament, and statements of the EU High Representative and the President of the European Council and is in line with principles of the United Nations and Helsinki Final Act. Hence, the unilateral standpoint of France is a flagrant violation of international law, as well as EU norms and interests.

The latest opinion poll held in Azerbaijan –before the military confrontation– shows that the EU is the most trusted international institution in Azerbaijan

Furthermore, by analyzing the post-ceasefire period 1994-2020, the paper comes to the conclusion that the responsibility for the eruption of the Second Karabakh war lies with Armenia. Even though Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territories have been recognized internationally as a sovereign part of Azerbaijan, since the ceasefire agreement concluded in 1994, Azerbaijan had been committed to a peaceful settlement. On the other hand, Armenia was reluctant to engage in result-oriented negotiations, likewise, with military and political provocations halted the negotiations so making the Second Karabakh war unavoidable.

Therefore, the commentary finds the accusations of France groundless and demonstrates that the detached foreign policy of France from EU norms and interests in the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has eroded its credibility as a mediator state. In view of these considerations, the stance of France could potentially undermine the positive image of the EU in Azerbaijan. The latest opinion poll held in Azerbaijan –before the military confrontation– shows that the EU is the most trusted international institution in Azerbaijan. Likewise, the biased stance of France could undermine the role of the EU in the resolution of other ethno-territorial conflicts and its reputation as a force for good.

Endnotes

1. Svante E. Cornell, Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), pp. 64-81.

2. Svante E. Cornell, Azerbaijan since Independence, (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2011), pp. 47-50.

3. Svante E. Cornell, The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, (Department of East European Studies, Uppsala University, 1999), p. 27.

4. Svante E. Cornell, “Turkey and the Conflict in Nagorno Karabakh: A Delicate Balance,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 34, No. 1 (January 1998), p. 58.

5. Cornell, The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, pp. 115-141.

6. “OSCE Minsk Group Co-Chairs Issue Statement on Nagorno-Karabakh,” Minsk Group, (November 29, 2007), retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.osce.org/mg/49237.

7. “Statement by the OSCE Minsk Group Co-Chair Countries,” Minsk Group, (July 10, 2019), retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.osce.org/mg/51152.

8. Sabine Freizer, “Twenty Years after the Nagorny Karabakh Ceasefire: An Opportunity to Move towards more Inclusive Conflict Resolution,” Caucasus Survey, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 2015), pp. 109-122.

9. Elmar Mustafayev, “Nagorno-Karabakh: Forgotten, Not Frozen,” Visions of Azerbaijan, (Summer 2016), retrieved November 21, 2020, from http://www.visions.az/en/news/796/02e4c34c/.

10. Eduard Abrahamyan and Movses Ter-Oganesyan, “Geopolitical Implications amid Armenia’s Velvet Revolution,” The National Interest, (May 14, 2018), retrieved November 21, 2020, from https://nationalinterest.org/feature/geopolitical-implications-amid-armenias-velvet-revolution-25823.

11. Joshua Kucera, “Azerbaijan Sees New Possibilities for Dialogue with Armenia,” Eurasianet, (January 9, 2019), retrieved November 22, 2020, https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-sees-new-possibilities-for-dialogue-with-armenia.

12. Ilgar Gurbanov, “Armenia’s Approach to Conflict Settlement Leads to Deadlock,” The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, (June 27, 2019), retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13576-armenias-approach-to-conflict-settlement-leads-to-deadlock.html.

13. Joshua Kucera, “After Peace Negotiations, Threats of War Break Out Between Armenia and Azerbaijan,” Eurasianet, (April 1, 2019), retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://eurasianet.org/after-peace-negotiations-threats-of-war-break-out-between-armenia-and-azerbaijan.

14. Joshua Kucera, “Pashinyan Calls for Unification between Armenia and Karabakh,” Eurasianet, (August 6, 2019), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://eurasianet.org/pashinyan-calls-for-unification-between-armenia-and-karabakh.

15. Joshua Kucera, “Armenia and Karabakh Announce Construction of Third Connecting Highway,” Eurasianet, (July 25, 2019), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://eurasianet.org/armenia-and-karabakh-announce-construction-of-third-connecting-highway.

16. Muhittin Ataman, “What’s Going on between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Tovuz Region?” Daily Sabah, (July 21, 2020), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/columns/whats-going-on-between-azerbaijan-and-armenia-in-tovuz-region.

17. Vasif Huseynov, “Armenian Resettlement from Lebanon to the Occupied Territories of Azerbaijan Endangers Peace Process,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, (September 23, 2020), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://jamestown.org/program/armenian-resettlement-from-lebanon-to-the-occupied-territories-of-azerbaijan-endangers-peace-process/.

18. “Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), Title V: General Provisions on the Union’s External Action and Specific Provisions on the Common Foreign and Security Policy - Chapter 1: General Provisions on the Union’s External Action - Article 21,” (February 7, 1992), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:12008M021.

19. “The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU),” Article 10 #1-2c, (December 17, 2007), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2007:306:FULL:EN:PDF.

20. “Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), Title V: General Provisions on the Union’s External Action and Specific Provisions on the Common Foreign and Security Policy - Chapter 2: Specific Provisions on the Common Foreign and Security Policy - Article 24,” (February 7, 1992), retrieved March 23, 2021, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=

celex%3A12012M024.

21. “A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy,” The European External Action Service, (June 2016), retrieved November 25, 2020, from https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf.

22. Nathalie Tocci, The EU and Conflict Resolution: Promoting Peace in the Backyard, (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2007), p. 8.

23. Nino Mikhelidze, “Eastern Partnership and Conflicts in the South Caucasus: Old Wine in New Skins?” IAI Documenti, Vol. 9, No. 23 (September 2009), pp. 1-14.

24. Ilgar Gurbanov, “Outcomes of the Eastern Partnership Brussels Summit for Azerbaijan,” Vocal Europe, (December 20, 2017), retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://www.vocaleurope.eu/outcomes-of-the-eastern-partnership-brussels-summit-for-azerbaijan/.

25. “Azerbaijan Objects to Riga Summit Joint Declaration,” ANEWS, (May 25, 2015), retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://anews.az/en/azerbaijan-objects-to-riga-summit-joint-declaration/.

26. Ilgar Gurbanov, “Strategic Partnership Agreement: A New Chapter in EU-Azerbaijan Relations,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, (June 22, 2017), retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://jamestown.org/program/strategic-partnership-agreement-new-chapter-eu-azerbaijan-relations/.

27. İlham Aliyev, Twitter, 6:03 PM, (November 29, 2017) retrieved from https://twitter.com/presidentaz/status/935871917093019648.

28. “Remarks by President Donald Tusk after His Meeting with President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev,” The European Council, (July 9, 2019) retrieved November 1, 2020, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/07/09/remarks-by-president-donald-tusk-after-his-meeting-with-president-of-azerbaijan-ilham-aliyev/.

29. “Remarks by President Donald Tusk after His Meeting with Prime Minister of Armenia Nikol Pashinyan,” The European Council, (July 10, 2019) retrieved November 1, 2020, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/07/10/remarks-by-president-donald-tusk-after-his-meeting-with-prime-minister-of-armenia-nikol-pashinyan/.

30. “Council Conclusions on Eastern Partnership Policy Beyond 2020,” General Secretariat of the Council, (May 11, 2020), retrieved November 25, 2020, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/43905/st07510-re01-en20.pdf.

31. “Remarks to the UN Security Council on the EU’s role in international security,” The European External Action Service, (May 28, 2020), retrieved November 25, 2020, from https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-Homepage/80041/remarks-un-security-council-eu%E2%80%99s-role-international-security_ja.

32. “European Parliament Recommendation of 19 June 2020 to the Council, the Commission and the Vice-President of the Commission/High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on the Eastern Partnership, in the run-up to the June 2020 Summit (2019/2209 (INI)),” European Parliament, (June 19, 2020), retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0167_EN.html.

33. “Joint Statement by the Chair of the Delegation, MEP Marina KALJURAND, the European Parliament’s Standing Rapporteur on Armenia, MEP Traian BĂSESCU, and the European Parliament’s Standing Rapporteur on Azerbaijan, MEP Željana ZOVKO on the Construction of a New Highway between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh,” European Parliament, (June 10, 2020), retrieved November 26, 2020, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/208877/KALJURAND_BASESCU_ZOVKO_Joint%20statement_new%20highway%20between%20Armenia%20and%20Nagorno%20Karabakh.pdf.

34. Thomas de Wall, Black Garden, (New York: New York University Press, 2003), p. 258.

35. “Azerbaijan, France Mull Energy Cooperation,” Azernews, (September 22, 2020), retrieved March 21, 2020, from https://www.azernews.az/business/169180.html.

36. “Azerbaijan Mulls French Calls to Join Terrorism Fight in the Sahel,” RFI, (January 17, 2020), retrieved March 21, 2020, from https://www.rfi.fr/en/europe/20200117-Azerbaijan-mulls-French-calls-join-terrorism-fight-Africa-Sahel-Nagorno-Karabakh-Ira.

37. “Macron Criticizes Turkey’s ‘Warlike’ Rhetoric on Nagorno-Karabakh,” Euractiv, (September 30, 2020), retrieved November 21, 2020, from https://www.euractiv.com/section/azerbaijan/news/macron-criticises-turkeys-warlike-rhetoric-on-nagorno-karabakh/.

38. “Macron Reprimands Turkey, Accuses Erdogan of Sending ‘Jihadists’ to Azerbaijan,” France 24, (October 2, 2020), retrieved November 21, 2020, from https://www.france24.com/en/20201002-macron-reprimands-turkey-accusing-erdogan-of-sending-jihadists-to-azerbaijan.

39. “Azerbaijan Leader Demands Full Armenian Withdrawal, Apology Before any Ceasefire,” Al Arabiya, (October 4, 2020), retrieved November 21, 2020, from https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2020/10/04/Azerbaijan-s-Aliyev-says-no-end-to-fighting-until-Armenia-sets-pullout-timetable-.

40. “Ilham Aliyev: Armenian Government Overestimated Its Global Role,” Al Jazeera, (October 3, 2020), retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://www.aljazeera.com/program/talk-to-al-jazeera/2020/10/3/ilham-aliyev-armenian-government-overestimated-its-global-role/.

41. “French Minister Urges Meutrality on Nagorno-Karabakh,” Anadolu Agency, (October 14, 2020), retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/french-minister-urges-neutrality-on-nagorno-karabakh/2005427.

42. “Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev: We Never Deliberately Attacked Civilians,” France 24, (October 14, 2020), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/2020

1014-azerbaijani-president-ilham-aliyev-we-never-deliberately-attacked-civilians.

43. Zacharie Gross, Twitter, 6:34 PM (October 18, 2020), retrieved from https://twitter.com/GrossZacharie/status/1317836513124749314.

44. “Members of Non-Aligned Movement Refuse to Adopt Document against Azerbaijan,” Report News Agency, (October 23, 2020), retrieved November 22, 2020, from https://report.az/en/karabakh/hikmat-hajiyev-comments-on-discussions-in-un-security-council-on-armenian-azerbaijani-conflict/.

45. “France Openly Pursuing Pro-Armenian Policy - Top Azerbaijani Official,” Azernews, (November 11, 2020), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://www.azernews.az/nation/172509.html.

46. “French Senate Adopts Resolution Urging Government to Recognize Nagorno-Karabakh,” TASS, (November 25, 2020), retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://tass.com/world/1228017.

47. “France Wants International Supervision in Nagorno-Karabakh, Worries about Turkey’s Role,” Daily Sabah, (November 20, 20020), retrieved March 15, 2021, from https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/france-wants-international-supervision-in-nagorno-karabakh-worries-about-turkeys-role.