The conventional paradigm considers only the magnitude of energy consumed per capita as an indicator of the country’s “progress,”1 but it does not take into consideration the social, environmental, and security impacts of energy consumption.2 With this paradigm based on increased consumption of fossil fuels,3 the resulting environmental, social and economic costs, are enormous.

Today, the world is facing massive environmental challenges. Global warming and climate change, ozone depletion, loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, and air and water pollution are global problems with wide-ranging impacts on human populations. In addition to environmental problems, there are also serious security issues associated with the large-scale use of fossil and nuclear fuels. Tensions arise from depletion of global fossil fuel resources,4 uncertainties in energy prices and energy availability,5 geopolitical tension caused by the concentration of oil and gas resources in a few regions of the world, and the risk of nuclear proliferation threatening global security.6 Political pressures surrounding fossil fuels can lead to unrest, regime changes, and even war.

These situations can lead to extreme social hardships.7 Therefore, increasing energy security risks are a growing concern for developed and developing countries alike. Energy security has, therefore, returned to the top of the international agenda like in the 1970s8 and now is considered one of the most important challenges to the world’s peace and security.

Renewable energy has become a high priority among energy policy strategies on a global scale

The conventional energy paradigm is clearly incapable of solving these significant political and social problems. This situation has called for a paradigm shift in energy policy. As a matter of fact, a paradigm shift in the objectives of energy policy is currently taking place—towards security of supply and climate change.7 Sustainability is one of the key concepts of the new paradigm. Cost-effective, sustainable energy policy should aim to reduce energy use before seeking to meet the remaining demand by the cleanest means possible.

The global trend at the moment is towards the energy strategies built around the following hierarchy in energy options from the most sustainable to the least sustainable:9

- Energy conservation: improved energy efficiency and rational use of energy

- Increasing use of renewable sources

- Exploitation of un-sustainable resources using low-carbon technologies

The shift to renewable, energy-efficient and low-carbon technologies driven by energy security and climate change concerns is making progress although at a slower pace than desired. A transition from fossil fuels to a non-carbon-based economy will more likely occur, over the longer-term.

Global Trends in Renewable Energy

Renewable energy, which constitutes one of the three essential pillars of the new energy paradigm,10 has become a high priority among energy policy strategies on a global scale. In most countries, depending on the ongoing paradigm change, renewable energy policies are evolving rapidly.11 Many countries are in the process of deregulating and restructuring their electric power industries. The fundamental transition of the world’s energy markets has begun.12

As illustrated in Table 1 and 2, a number of developed, transitioning countries, and developing countries have already adopted some type of policy to promote renewable power generation. The most common existing policy is the feed-in law13 (feed-in tariffs), which has been enacted in many countries and regions in recent years. There are many other forms of policy support for renewable power generation, including Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) policies, direct capital investment subsidies or rebates, tax incentives and credits, sales tax and value added tax (VAT) exemptions, direct production payments or tax credits (i.e., per kWh), green certificate trading, net metering, direct public investment or financing, and public competitive bidding for specified quantities of power generation.14

In at least 66 countries worldwide, policy targets for renewable energy have been implemented. Included among these countries are all 27 European Union countries, 29 U.S. states (and D.C.), and 9 Canadian provinces.14 Table 3 demonstrates that most targets are for shares of Electricity production, primary energy,15 and/or final energy16 by a specific date. Most targets aim for the 2010– 2012 timeframe, although an increasing number of targets aim for 2020. There is now an EU-wide target of 20 percent of final energy consumption17 by 2020, and a Chinese target of 15 percent of primary energy by 2020. Most countries have set high goals for the utilization of renewable energy by the middle of the century, but present day usage of renewable sources of energy is dominated by developed nations such as the United States, Germany, Spain and Denmark, as well Brazil and China, the leading developing nations. Hydroelectric power is the dominant renewable energy due to its widespread use but wind energy and solar power are fast growing forms of renewable energy sources.14

The European Union (EU) is presently leading global action in accelerating the transition to renewable energy and a low-carbon economy. According to the European Energy Commissioner Andris Piebalgs, “we are at the beginning of third industrial revolution - the rapid development of an entirely new energy system. We can expect a massive shift towards a carbon-free electricity system, huge pressure to reduce energy consumption and transport on the basis of renewable electricity.”18

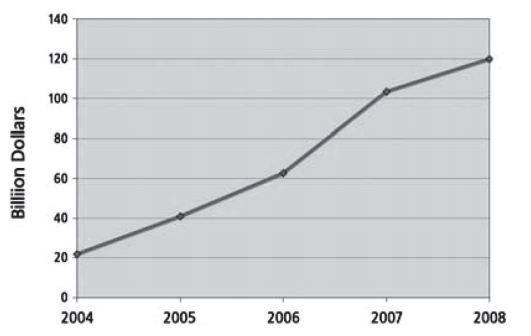

The EU is heading towards the Third Industrial Revolution by making some binding commitments. On March 2007, European leaders signed up to a binding EU-wide target to source 20% of their energy needs from renewables such as biomass, hydro, wind, and solar power by 2020. On 23 January 2008, the European Commission put forward differentiated targets for each EU member state, based on their respective per capita GDP. As part of the overall target, achieving at least 10% of their transport fuel consumption from bio-fuels is a binding minimum target for each member state. Under President Obama, the United States is also increasing its reliance on green energy: 25% of its electricity is to be generated from renewable energy sources by 2025. As a consequence of these new policies, global investment in renewable energy and the installed renewable capacity of the world has increasingly grown over the past decade, as illustrated in Figures 1-4.14

According to REN21 Renewables Global Status Report, many indicators of renewable energy have shown dramatic gains in the 2000s. Annual renewable energy investment has reached $120 billion in 2008. Global power capacity from new renewable energy sources (excluding large hydro) expanded to 280 GW in 2008 – a 16 percent rise from the 240 GW in 2007 and a 75 percent increase from 160 GW in 2004, as illustrated in Table 1. The top six countries were China (76 GW), The United States (40 GW), Germany (34 GW), Spain (22 GW), India (13 GW), and Japan (8 GW). The capacity in developing countries grew to 119 GW or 43 percent of total with China (small hydro and wind) and India (wind) leading the increase. A significant milestone was reached in 2008 when added power capacity from renewables in both the United States and the European Union exceeded added power capacity from conventional power (including gas, coal, oil and nuclear) and renewables represented more than 50% of total added capacity.

According to European Photovoltaic Industry Association (EPIA), global installed solar photovoltaic power grew by 44 percent in 2009 funded by German subsidies. The global solar photovoltaic electricity (PV) market counted an additional increase in installed capacity of about 6.4 GW in 2009, reaching a total capacity of over 20 GW worldwide. This has been the most important annual capacity increase ever and is particularly impressive in light of the difficult financial and economical circumstances during the past year. Germany was the largest demand market last year, adding 3 gigawatts (GW), followed by Italy, Japan and the United States. Germany will likely remain the biggest demand market in 2010, according to the EPIA. In 2010, global cumulative installed PV capacity is expected to grow by at least 40%, while the annual growth is expected to increase by more than 15%. Despite strong growth, solar power still provides only about 0.5 percent of global installed electricity capacity.

The huge potential of Turkey in renewables like wind, solar, and geothermal has not been used efficiently until recently

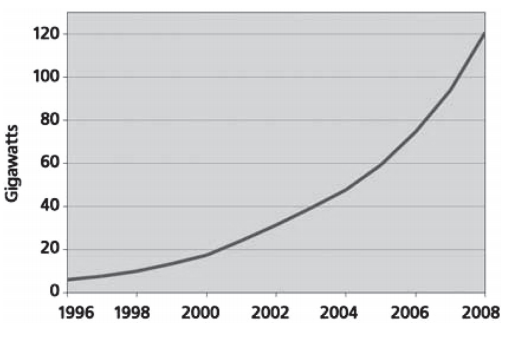

Among new renewables (renewables excluding large hydropower), wind power was the largest addition to renewable energy capacity. Since 2000, wind power has the highest capacity of all renewables.

The Global Wind Energy Council announced that the world’s wind power capacity grew by 31% in 2009, adding 37.5 gigawatts (GW) to bring total installations up to 157.9 GW. The main markets driving this significant growth continue to be Asia, North America, and Europe, each of which installed more than 10 GW of new wind capacity in 2009. China was the world’s largest market in 2009, more than doubling its wind generation capacity from 12.1 GW in 2008 to 25.1 GW at the end of 2009 with new capacity additions of 13 GW. A newly added capacity of 1,270 MW in India and some smaller additions in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan make Asia the biggest regional market for wind energy in 2009, with more than 14 GW of new capacity. The U.S. wind energy market installed nearly 10 GW in 2009, increasing the country’s installed capacity by 39% and bringing the total installed grid-connected capacity to 35 GW. Europe, which has traditionally been the world’s largest market for wind energy development, continued to see strong growth, also exceeding expectations. In 2009, 10.5 GW were installed in Europe, led by Spain (2.5GW) and Germany (1.9 GW). Italy, France, and the UK all added more than 1 GW of new wind capacity each. 39% of all new capacity installed in 2009 was wind power, followed by gas (26%) and solar photovoltaic (16%). Europe decommissioned more coal and nuclear capacity than it installed in 2009. Taken together, renewable energy technologies account for 61% of new power generating capacity in 2009. As demonstrated, the wind energy industry has emerged as a major growth sector in a number of countries.

Among developing countries, China and India are increasingly playing a major role in both the manufacturing and installation of wind energy. While leading wind turbine manufacturers are based in industrialised countries like Denmark, Germany, and Spain, India and China have caught up very rapidly– both through building up their own wind industries and through support for wind energy deployment. Within the last decade, they managed to progress from having no wind turbine manufacturers to hosting leading companies capable of manufacturing whole wind turbines. It should be emphasized that these countries can serve as important examples of how leapfrogging,19 is possible in terms of industrial development and technology adoption in the energy sector.

Turkey’s Renewable Energy Policies and Strategies

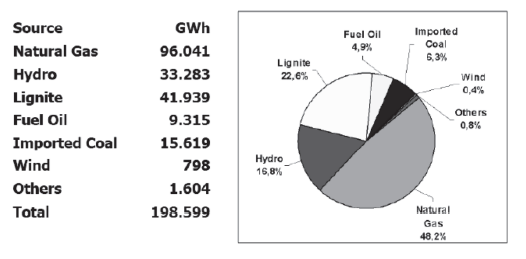

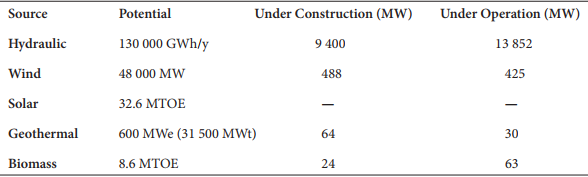

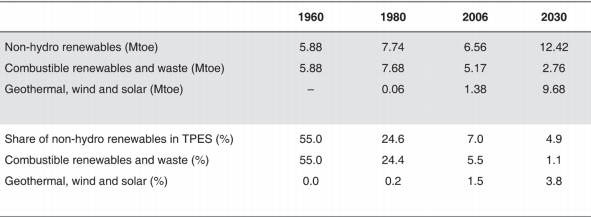

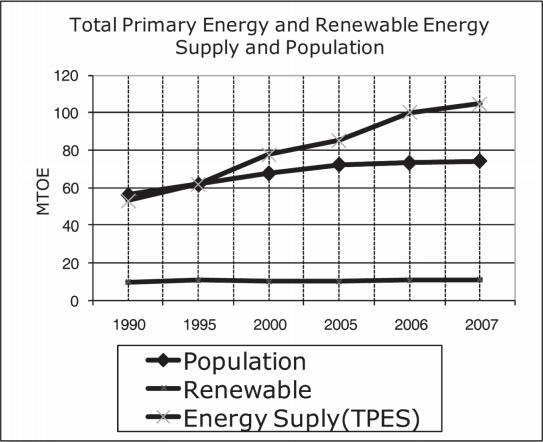

Turkey has substantial renewable energy potential. Renewables make the second-largest contribution to domestic energy production and consumption after coal.20(See Figure 5)21 However commercial use of renewable energy in Turkey, excluding large-scale hydropower, has not developed in proportion to its large resource base. Renewable energy use has been dominated by large hydro and biomass (mostly wood and animal wastes).20 The huge potential of Turkey in renewables like wind, solar, and geothermal has not been used efficiently until recently22. (See Table 4 &Table 5)23 Unfortunately, the use of new renewables (renewables excluding large hydro) is therefore still extremely limited because oflow growth.24 Although the absolute value of renewable energy use grows, its share of the Total Primary Energy Supply (TPES) does not increase since it doesn’t grow in proportion with energy consumption as illustrated in Figure 6. So, the share of fossil fuels continues to increase.24

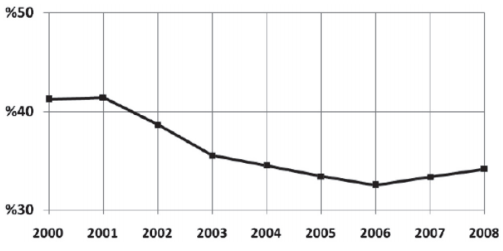

In the event that Turkey continues pursuing the same policy, it is more likely that renewable shares will continue decreasing rather than increasing. Just as, total share of renewable in TPES has declined depending on, mainly, decreasing biomass use (Table 5)23 and the growing role of natural gas in the system. It has been estimated that the share of renewable energy will decrease to % 9 of TPES in 2020.20 As illustrated in Figure 7, the share of installed renewable capacity in total installed capacity dramatically decreased in the last decade.25 In addition, Turkey’s highly supply-oriented energy policy dominated, with emphasis placed on ensuring additional energy supply to meet the growing demand, while the sustainability criteria remained a lower priority.

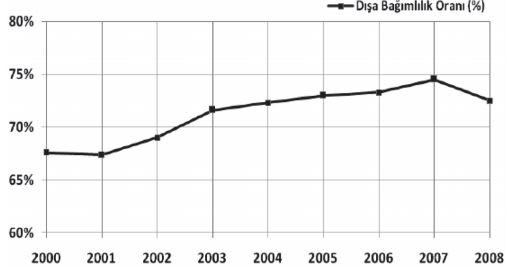

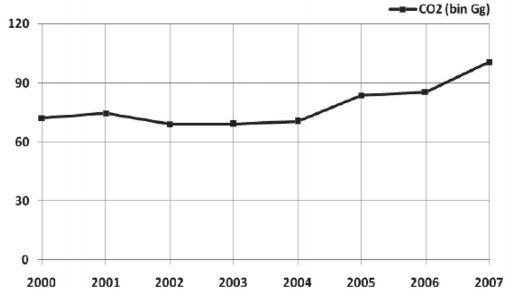

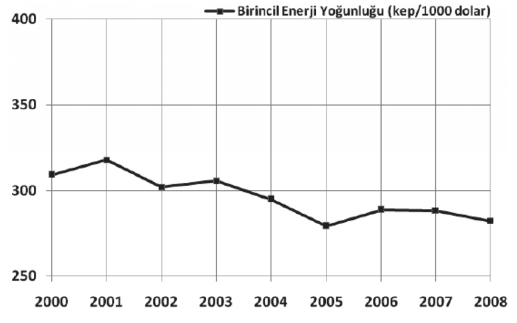

Turkey is currently faced with serious environmental and energy security challenges. As illustrated in Figure 8, the share of imported fuels continues to increase and more than about 70% of the total primary energy consumption in the country is met by imports.25 And as illustrated in Figures 9 and 10, total CO2 emissions are rapidly increasing.25 Energy intensity remains too high in comparison to the other OECD Countries.26 Therefore, environmental and energy security risks continue to increase in Turkey. Turkey’s energy situation is evidently unsustainable and in conflict with the emerging energy paradigm as well as with contemporary global energy trends. Changing these unsustainable patterns is one of the main challenges for Turkey. It is clear that the existing renewable energy potential must be realized in a reasonable time period. It is a step in the right direction that decision makers in Turkey have already placed on the agenda to utilize hydro and other renewable resources such as wind, solar, and geothermal energy to meet growth in demand in a sustainable manner.

Following the enactment of the Renewable Energy Law in May 2005, investor interest in the renewable energy sector has risen distinctively

Recently, progress has been made with regard to renewable energy regulations. The Electricity Market Law, which was enacted in March 2001, authorized the Energy Market Regulatory Agency (EMRA) to take the necessary measures to promote the utilization of renewable energy resources27. The First Renewable Energy Law No. 5346, entered into force in 200528. The Renewable Energy Law was a key step for strengthening the country’s decentralized renewable energy sector. However, much more still needs to be done. It is an urgent need to improve the country’s Renewable Energy Strategy. Turkey is also trying to take new steps for stimulating renewable energy use and investments to accelerate the transition to renewable energy.

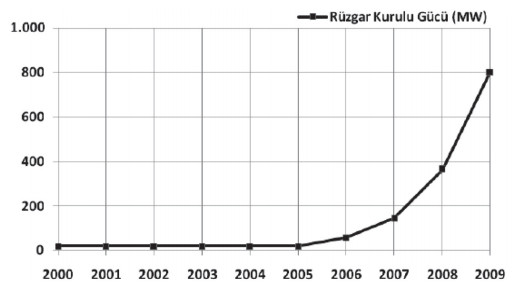

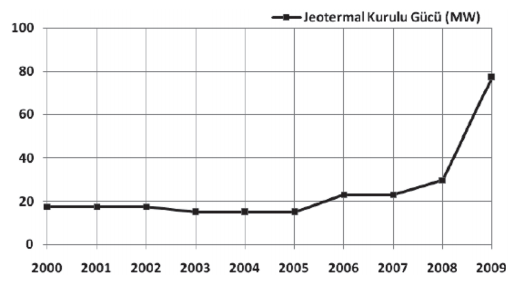

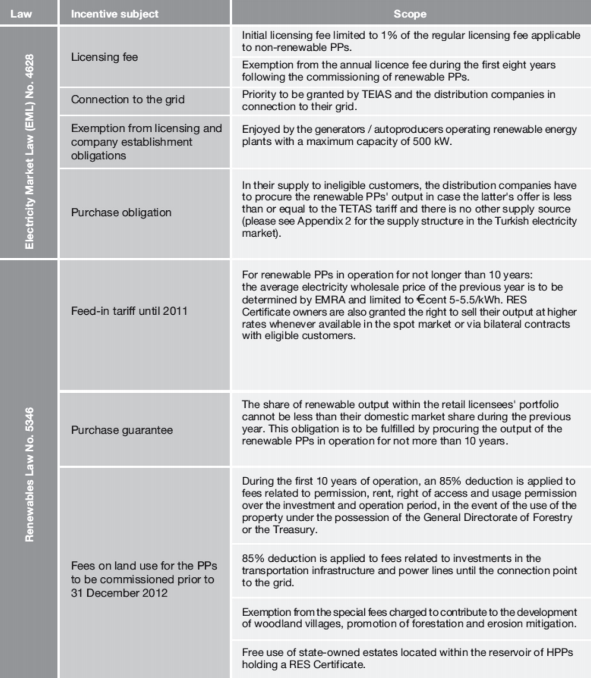

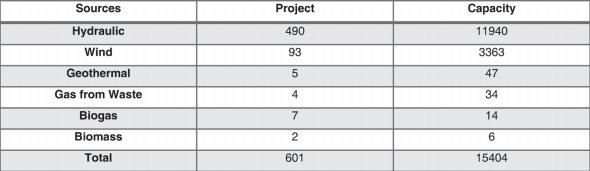

Following the enactment of the Renewable Energy Law No. 5346 in May 2005, investor interest in the renewable energy sector has risen distinctively.29 This is especially the case in relation to the generation of electricity through hydro plants and wind farms22. A sharp increase in the number of licence applicants for renewables has occurred. Despite a rise in the numbers, the interest in renewable energy projects was hindered by the lenders’ reluctance because of the uncertainty in the purchase guarantees. As a result, the government introduced an important series of amendments in 200730 and 200831. The amendment to the law in May 2007 secured a constant purchase price for all types of renewable sources. Current incentives to promote renewable energy by The Electricity Market Law with No. 4628 and Renewable Energy Law with No. 5346 are shown in Table 6.32 Following these amendments significant progress has been made. As illustrated in Table 7, a total of 601 renewable projects with a capacity of 15500 MW have been licensed by 2009.22 The efforts successfully resulted in substantial increases in the wind and geothermal capacity, as illustrated in Figures 11-12. However, as Tables 4 and 7 demonstrate22 solar capacity has not developed and it clearly needs further promotion. Therefore, a Draft Amendment to the Renewable Energy Law has recently been prepared in order to provide further incentives to the renewable energy sector. This Draft Law will address issues such as the determination of different purchase prices for the electricity produced from different types of renewable energy, simpler trade mechanism for renewable pool, and additional support in cape electro-mechanical equipment manufactured in Turkey. According to this Draft Law, different prices varying from Euro Cent 5 /kWh to Euro Cent 18 /kWh will be applied to the purchase of electricity depending on the type of renewable energy resource used (seeTable 8).32 It is considered to be a more realistic approach than the Renewable Energy Law since it contemplates the application of higher and different prices depending on the type of renewable energy resources, and thus, responds better to the needs of the sector. The aim is mainly to expand the utilization of solar energy for generating electrical energy in Turkey. However, the Last Amendment to the Renewable Energy Law has yet to be implemented. The Draft Amending Law was supposed to pass the National General Assembly on June, 2009. But it was suspended to reconsider purchase prices because it would create an extra burden on the treasury. It is still under discussion in the Turkish National General Assembly.

In Strategy Paper, the long term primary target is “to ensure that the share of renewable resources in electricity generation is increased up to at least 30% by 2023”

Turkey is also now at the stage of setting targets for renewable energy development. The Higher Board of Planning adopted the “Electric Energy Market and Supply Security Strategy Paper”33 in May 2009. In this Strategy Paper, the long term primary target is “to ensure that the share of renewable resources in electricity generation is increased up to at least 30% by 2023.” This strategy document was published as a general road map to increase the share of renewable energy in electricity generation. Within the framework of the Strategy Paper, long term efforts will take into consideration the following targets by 2023:

- Ensure that available technically and economically hydro-electric potential is fully utilized,

- Increase installed wind energy power to 20,000 MW,

- Commission all geothermal potential of 600 MW that is currently considered as suitable for electric production,

- Generalize the use of solar energy for generating energy and ensure maximum utilization of country potential,

- Follow and implement closely technological advances in the use of solar energy for electricity generation,

- Amend accordingly the Law No. 5346 to encourage generation of electricity using solar energy,

- Prepare and produce plans that will take into account the potential changes in utilization potentials of other renewable energy resources based on technological and legislative developments and in case of increases, utilization of such resources, share of fossil fuels and particularly of imported resource, will be reduced accordingly.

Recently, the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources prepared its Strategic Plan covering the period between 2010 and 2014.25 Increasing the share of renewable energy resources is one of the plan’s goals to provide energy supply security.

Near-term targets are the following:

- The hydroelectricity plans of 5,000 MW under construction will be completed by 2013.

- The wind plant installed capacity, which was 802.8 MW as of 2009, will be increased up to 10,000 MW by 2015.

- The installed capacity for the geothermal plant will be increased from 77.2 MW in 2009 up to 300 MW by 2015.

Both of this long term and near term strategy plans are not, on their own, legally binding. It is, however, expected that their provisions will be incorporated into future regulations and legislation.

Considerations

Although Turkey has significant renewable energy resources for electricity production, this potential has not yet been used efficiently. The legislator in Turkey has taken important steps in order to promote the use of renewable energy resources in the production of electricity and to encourage the investments in this market. However, Turkey is making relatively slow progress in the realization of its aims of renewable energy. The reason for this is that policies and measures adopted in the country aiming to enhance the use of renewable energy sources are mainly driven by the requirements of the EU accession process. It seems that Turkey couldn’t internalize the new energy paradigm specifically enough, although it has adapted to the EU’s regulations. First of all, the paradigm change should correctly be understood and internalized by the Turkish government. This would allow the government to set up a legal and institutional framework conducive to this new energy paradigm, draws up the specifications of what the energy system of the future should look like, and formulate policy adopting the new energy paradigm. Second, the administrative staff should be educated and trained on how to implement and internalize the new energy paradigm, because one of the key aspects of this process is a conceptual re-invention of how energy consumption and production is done and how the related institutions operate.

Turkey should undertake comprehensive efforts to abolish the weaknesses in its policies and regulations and how they are implemented. It is a race against the time as leading countries compete with each other in this race towards the Third Industrial Revolution. If Turkey doesn’t want to miss out on the Third Industrial Revolution, and if it wants to catch up with leading developing countries, such as China and India, which managed to catch up with the developed countries, it should immediately accelerate the transition process to renewable energy.

Technological leapfrogging is one of the ways to achieve this goal.34 From a conventional point of view, developing countries passively adopt technology as standard products, which have been developed in industrial countries. However, leapfrogging represents an attractive option for these late industrializing countries. The role of technological leapfrogging within a sustainable development context35 is not automatic, since leapfrogging alone does not guarantee or even encourage prosperity. However, from a more philosophical perspective, it has been argued that there is, in fact, no alternative to leapfrogging for developing countries.36 If these countries do not attempt to update their technologies, they face exclusion from the global mainstream economic trends as well as continued deprivation and poverty for their people. Turkey should also not repeat the energy history of the industrialized countries37. Similarly to the success stories of the Indian and Chinese wind industries, leapfrogging opportunities may also exist for Turkey with its vast potential of renewable resources.

Decision makers in Turkey should internalize the concept of leapfrogging as an integral part of their renewable energy vision and should seek to implement its many potential applications. However, in order to protect the investment of the country’s scarce resources available for advanced technologies, as is the case in most developing countries, and to distinguish between circumstances where leapfrogging may or may not be successful, careful and detailed analyses should be carried out.

Tables

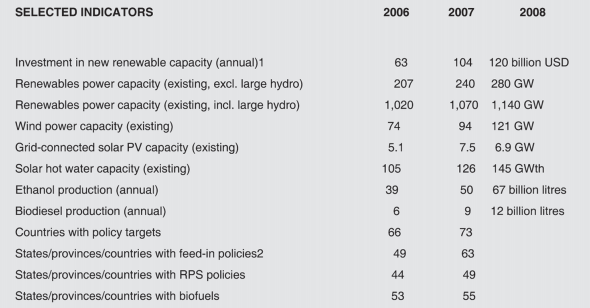

Table 1. Global Indicators for evolution of renewable energy 2006-2008.12

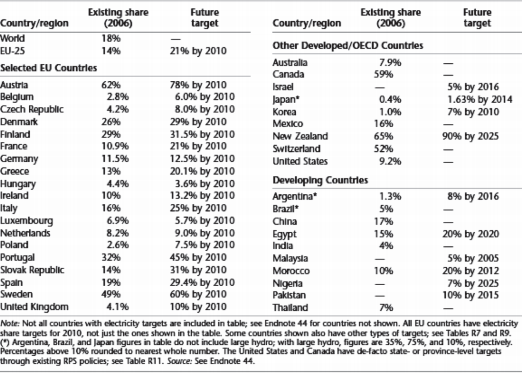

Table 2. Renewable energy promotion policies.12

* In some states of the Country

Table 3. Share of Electricity from Renewables, Existing and Targets.14

Figure 1. Global Investment in Renewable Energy.12

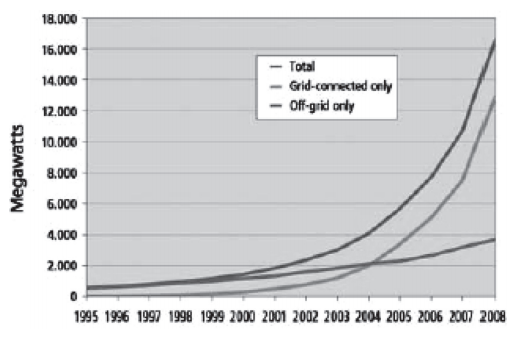

Figure 2. Existing World Capacity for Wind Power.12

Figure 3. Existing World Capacity for Solar PV.12

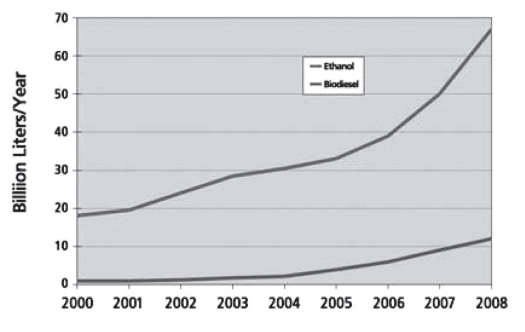

Figure 4. Ethanol and biodiesel production, 2000-2008.12

Figure 5. Generation by Source in Turkey by 2008.25

Table 4. Comparison of renewable energy potential with capacity under construction.22

Table 5. Evolution of non-hydro renewables in Turkey, 1960-2030.23

Figure 6. Total Primary Energy and Renewable Energy Supply and Population of Turkey between 1990–2007.24

Figure 7. Share of renewable power including large hydro in total install capacity.25

Figure 8. Import Dependency of Turkey.25

Figure 9. CO2 emission from electrical energy production in Turkey.25

Figure 10. Primary energy density of Turkey.25

Figure 11. Evolution of installed capacity for wind power in Turkey.25

Figure 12. Evolution of installed capacity for geothermal power in Turkey.25

Table 6. Existing incentives to promote investment in renewable energy.32

Table 7. Renewable Energy Generation Licence by April 2009.22

Table 8. Proposed feed-in tariff structure in Draft Amendment Law.32

Endnotes

- Rajni Bakshi, “A new energy paradigm,” The Hindu, Online edition of India’s National Newspaper, Dec. 24, 2000.

- Amulya Kumar N. Reddy, “Development, Energy and Environment Alternative Paradigms”, retreived from http://amulya-reddy.org.in

- P. D. Rakin and R. M. Margolis, “Global Energy, Sustainability, and the Conventional Development Paradigm,” Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, Vol. 20, No. 4 , (1998), pp. 363-383.

- Hal Turton and Leonardo Barreto, “Long-term security of energy supply and climate change,” Vol. 34. No.15 (October, 2006), pp. 2232-2250.

- Eshita Gupta, “Oil vulnerability index of oil-importing countries,” Energy Policy, Vol. 36, (January, 2008), pp. 1195–1211.

- James P. Dorian, Herman T. Franssen and Dale R. Simbeck, “ Global challenges in energy,” Energy Policy, Vol. 34, No. 15 (October, 2006), pp. 1984-1991.

- Valeria Costantini, Francesco Gracceva, Anil Markandya and Giorgia Vicini, “Security of energy supply: Comparing scenarios from a European perspective,” Energy Policy, Vol. 35, No. 1 (January, 2007), pp. 210-226.

- William J. Nuttall and Devon L. Manz M. Totten, “A New Energy Security Paradigm for the Twenty-First Century,” EPRG Working Paper, retrieved May 1, 2010, from http://www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/eprg0731.pdf.

- Energy Policy Statement: 09/03, Institution of Mechanical Engineers retrieved May 2010 from http://www.imeche.org/NR/rdonlyres/9C7E8DCD-150C-4ECA-A387-D71DEAAAAFAD/0/EnergyHierarchyIMechEPolicy.pdf.

- Jeremy Rifkin, “Leading the Way to the Third Industrial Revolution and a New Social Europe in the 21st Century,” European TIR Paper, retrieved May, 2010, from http://www.foet.org/packet/European.pdf.

- Roland Menges, “Supporting renewable energy on liberalised markets: green electricity between additionality and consumer sovereignty,” Energy Policy, Vol. 31 (2003), pp. 583-596.

- REN 21(Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21th Century), “Renewables Global Status Report 2009 Update,” retrieved May, 2010 from http://www.ren21.net/pdf/RE_GSR_2009_Update.pdf.

- A legal obligation on utilities to purchase electricity from renewable sources.

- REN 21(Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21th Century), “Renewables Global Status Report 2007,” retrieved on May 2010 from http://www.ren21.net/globalstatusreport/g2007.asp.

- Energy that has not been subjected to any conversion or transformation process.

- Form of energy available to the user following the conversion from primary energy carriers such as crude oil, natural gas, nuclear energy, coal and regenerative energies.

- Sum of the energy supplied to the final user for all energy uses.

- A. Piebalgs, Energy Commissioner, “European Response to energy challenges,” Speech at the EU Energy and Environment Law and Policy Conf. Brussels (January 22, 2009), retrieved May, 2010, from http://www.energypolicyblog.com/2009/02/10/european-union-at-the-eve-of-the-third-industrial-revolution%E2%80%9D/.

- Technology leapfrogging is a term used to describe the bypassing of technological stages that other countries have gone trough. This is the definition used by Edward Steinmueller in the paper titled “ICTS’ and the; Possibilities for Leapfrogging by Developing Countries,” International Labor Review, Vol.140, No.2 (2001), p. 194.

- International Energy Agency, “Energy Policies of IEA Countries, Turkey 2005 Review”, 2005. http://www.iea.org/textbase/nppdf/free/2005/turkey2005.pdf

- F. Cecen, “Opportunities in Turkish Electricity Market” (May, 2009) retrieved May 1, 2010, from http// www.the-atc.org/events/c09/content/presentations/B2-Cecen-Firat-ICTAS.pdf.

- Burak Dilli, General Overview of Turkish Electricity Sector: Privatization & Renewable Energy, PP Presentation http://www.the-atc.org/events/c09/content/presentations/B2-Dilli-Budak-MinistryOfEnergy.pdf

- “Mediterranean Energy Perspectives 2008,” Observatoire Mediterraneen de l’Energie (OME), 2008, retrieved April 1, 2010, from htpp//www.omeenergie.com/mp-2008-12-5-en-335.pdf, pp. 315-378.

- Zeki Aybar Eriş, , “Great Wind Potential of Turkey,” POWER-GEN Europe 2007, Feria de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, June 26-28, 2007, p. 18-26.

- The Repuclic of Turkey Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources Strategy Plan 2010-2014, Ankara, 2010.

- Erdal Çalıkoğlu, “Energy Efficiency in Turkey” , TAIEX Workshop 25625 on Demand Side Management in Energy Efficiency, November 22-23, 2007, General Directorate of Electric Power Resources, Survey and Development Administration, Ankara, Turkey, retrieved May, 2010, from http://www.eie.gov.tr/duyurular/EV/TAIEX/taiex_sunular.html.

- Dirk Gaupp, “Turkey’s New Law on Renewable Energy Sources within the Context of the Accession Negotiations with the EU,” German Law Journal, Vol. 08, No. 04 (2007), pp. 413-416.

- Deger Boden, “Circuit Makers”, IFLR, International Financial Law review, (June 1, 2009).

- Hergüner Bilgen Özeke, “Turkey: The New Law on Renewable Energy Resources,” Environmental & Energy, (April 4, 2007).

- “Law on Utilization of Renewable Energy Sources for the Purpose of Generation Electricity,” Official Gazette No. 24335, dated 10.05.2005 (Law No.: 5346), Last Amendment: Official Gazette No. 26510, dated 02.05.2007.

- “Law on Utilization of Renewable Energy Sources for the Purpose of Generation Electricity,” Official Gazette No. 24335, dated 10.05.2005 (Law No.: 5346), Last Amendment: Official Gazette No. 270522, dated 03.12.2008.

- Energy, Utilities & Mining Sector, “Renewables Report On the sunny side of the street* Opportunities and challenges in the Turkish renewable energy market Industries,” (August 2009) retrieved May, 2010, from http://www.pwc.com/tr_TR/tr/publications/Assets/Renewables_Report_On_the_sunny_side_of_the_street.pdf.

- “Turkey’s Electric Energy Market and Supply Security Strategy Paper” with Res. No. 2009/11, dated 18.09.2009. http://www.enerji.gov.tr/yayinlar_raporlar/Arz_Guvenligi_Strateji_Belgesi.pdf

- Hasan Saygın, “Technological Leapfrogging in Energy in Developing Countries,” Enerji, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Ocak, 2006), p. 27. (in Turkish)

- Robert Davison, Doug Vogel, Roger Haris and Noel Jones, “Technology Leapfrogging in Developing Countries- an Inevitable Luxury,” Vol. 1, No.5 EJISDC (2000), pp. 1-10.

- W. Edward Steinmueller, “ICTs and the possibilities for Leapfrogging by Developing Countries,” International Labour Review, Vol. 140, No. 2 (2000).

- Hasan Saygın, ”Zero Emission Technologies for combating Global Heating,” Enerji, Vol. 11 (Mart, 2006) No. 3, p. 25.