Introduction

Controversy among the five littoral states over the legal regime of the Caspian Sea began with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. Until that time, the Caspian was considered a “common Sea” between Iran and the Soviet Union. However, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the number of littoral states increased from two to five, which in turn altered the geopolitical situation of the Sea. The birth of the new nation-states on the coast of the Sea transformed the region into a conflict area and the legal regime of the Sea became one of the contentious disputes among the bordering countries. The existence of offshore hydrocarbon resources in the Caspian and its location on a geopolitically significant transport route turned it into one of the main priority issues in the foreign policies of the littoral states and increased the need to find a legal solution, the absence of which prevented the disputing states from investigating the vast natural resources of the Sea. Therefore, since 1990, all five coastal states of the Sea have been more or less involved in the dispute over the ownership of the oil fields. The most adamant dispute has been between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

The dispute between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan revolves around three oil-rich sections of the trans-boundary sea territory of the Caspian Sea, namely, Azeri/Khazar-Omar, Chirag/Osman, and Kyapaz/Serdar in Azerbaijani and Turkmen, respectively. British Petroleum (BP) already developed the first two fields in accordance to the contract that signed with Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijani side relies on maps from the Soviet period, and claims that those fields were developed by its personnel. Turkmenistan insists on resolving the problem from the perspective of location, since these fields, particularly Kyapaz/Serdar, are located closer to its coastline.

Disagreement between the parties has periodically triggered diplomatic problems. As a result, in 2001, Turkmenistan closed its embassy to Azerbaijan. Later on, Turkmenistan even warned Azerbaijan that it would take the issue to international arbitration court. Therefore, the dispute is considered one of the reasons for the prolongation of the process on determining a new status for the Sea, since it may give a possibility to both side to identify their national sector and begin to explore their energy fields without the objection of other littoral states of the Caspian Sea. In the meantime, the parties have failed to build mutually beneficial bilateral relations, and the implementation of regionally important transportation projects such as the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) have been delayed.

Since 2017, with the opening of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway project, bilateral relations between the two parties have begun to normalize, and communication between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan has been restored. The signing of a new Convention on the status of the Caspian Sea in 2018 in Aktau was met with optimism regarding solutions for the disagreements, namely the delimitation of the seabed and construction of the TCP. In March of 2020, the President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov visited Azerbaijan and the parties signed a strategic partnership agreement.

Turkmenistan abstained from having a specific policy regarding the delimitation of the Sea, and its position changed over time

Thus, the scope of this research is to find out whether the new Convention on the status of the Caspian Sea of 2018 resolved the long-standing delimitation dispute between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, and to assess a the potential for implementing the TCP under the new conditions. The research consists of three parts. The first part describes the factors contributing to the dispute between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. The second part analyzes the legal status of the Caspian Sea, discusses the positions of the parties, their disagreements and the reasons behind the prolongation of the process for more than two decades, and then analyzes appropriate parts of the newly signed Convention of 2018. The third part assesses the impact of the Convention on the resolution of the delimitation dispute between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan and the potential for the realization of the TCP.

President Aliyev, Rouhani, Nazarbayev, Putin, and Berdimuhamedow of Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan respectively (L to R) attend the signing of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in Aktau, Kazakhstan, August 12, 2018. ALEXEI NIKOLSKY / Getty Images

President Aliyev, Rouhani, Nazarbayev, Putin, and Berdimuhamedow of Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan respectively (L to R) attend the signing of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in Aktau, Kazakhstan, August 12, 2018. ALEXEI NIKOLSKY / Getty Images

Areas of Disagreement

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, all five coastal states of the Caspian Sea have been more or less involved in the dispute over the ownership of the oil fields. Azerbaijan was one of the most adamant parties; Its stance was to divide the Sea into appropriate sectors on a median line, by which all coastal states would have sovereignty over a section of the biological resources, seabed, navigation, water column, and surface.1

Azerbaijan’s position relies on the designation of the Caspian Sea as a lake. In this regard, the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Hasan Hasanov stated, “Caspian is a lake and the international conventions say nothing about the status of the lakes. The talk can be only about the practice and Azerbaijan keeps just to this practice.”2

Azerbaijan’s position is reflected in its constitution of 1995, which claims that the “soil along with its mineral wealth, inland and territorial waters, continental shelf, flora and airspace over Azerbaijani territory are the exclusive ownership of the republic.”3 Regarding Russia’s imposition of 1921 and 1940 treaties, Azerbaijan claimed that these treaties only dealt with navigation and fishing, and did not define the legal status of the Sea, leaving the exploitation of the natural resources of the seabed an open issue. Azerbaijan also argued that the parties to the treaties were Iran and Soviet Russia and that, as such, these countries do not accommodate anymore the new, independent states of the Caspian Sea.4

For its part, Turkmenistan abstained from having a specific policy regarding the delimitation of the Sea, and its position changed over time. It was the first country to adopt a law by which the coastal water, twelve miles of territorial sea, and an exclusive economic zone were created. Meanwhile, Turkmenistan signed an agreement with foreign companies to develop its “Cheleken” offshore field in 1993.5 Two years later, it seemed to support the Russian and Iranian position that the condominium principle, which means that littoral states exercise their rights jointly, without dividing the Sea into national sectors, should be applicable until the littoral states come to a final agreement. In 1996, it switched toward Azerbaijan’s position and called for the division of the Sea according to national sectors.6 After a year, it came to an agreement with Azerbaijan to divide the seabed according to the median line principle, but could not agree from which point the median line should be measured.7

On July 8, 1998, Saparmurad Niyazov, then president of Turkmenistan, made a joint statement with Iran, which claimed that until the final status of the Sea was resolved, the Russo-Iranian treaties would remain in force. The sides agreed on the joint utilization of the Sea. In case of the division of the Sea among the littoral states, they insisted on an equal share, 20 percent for each country. Therefore, the dispute that emerged between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan over the oil fields in 1997 later on drove Turkmenistan toward the position of Iran.8

Thus, in February 1997, Saparmurad Niyazov announced that the Azeri and Chirag oil fields that were being exploited unilaterally by the international consortium Azerbaijan International Operating Company (AIOC) were part of Turkmenistan territory and claimed ownership of part of the profit.9

After half a year, another dispute was triggered between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan when State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) signed a contract with the Russian oil companies LUKoil and Rosneft for the exploration and development of the Kyapaz/Serdar oil field. Turkmenistan opposed the contract and demanded its immediate nullification.10 Turkmenistan’s claims to the first two oil fields, Azeri and Chirag, were rejected by Azerbaijan’s foreign minister. Azerbaijan justified its position with reference to the 1970 division of the Soviet part of the Caspian Sea into national sectors among the four Soviet Caspian Sea littoral states. In 1970, the USSR Ministry for Oil and Gas Industry had divided the north part of this imaginary line (Astara-Hasankulu) into sectors belonging to Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan. A provision of international customary law, the median line principle had been the basis for this ‘sectoral division.’ The Sea basin inside the sectoral division was considered the territory of the coastal state.11 According to that division above-mentioned oil fields was included to the part of the Azerbaijani sector. Additionally, Azerbaijan emphasized that the Western oil companies that had signed an agreement with Azerbaijan in 1994 for the development of these fields had made a sufficient investigation into the matter, and that if there had been any doubt, they would never have signed the agreement.12

In February 1998, both sides agreed that the Sea area between them would be divided along the median line principle, but disagreement occurred on how to determine the coordinates of the median line. While Azerbaijan insisted on the coordination of the median line from the last point of the Absheron Peninsula, Turkmenistan stated that it should be coordinated from mainland Azerbaijan, which would give a larger portion of the Sea to Turkmenistan and make all the disputed oil fields part of the Turkmenistan sector. “Drawing attention to the measurement of median line from mainland Azerbaijan the Turkmen side prefers to see Absheron Peninsula as a geographical irregularity.”13 Svante Cornell elucidates: “Absheron Peninsula protrudes far into the Caspian implies that the median line, if calculated according to normal practice from the actual shoreline of each country, would lie relatively far to the east… Therefore, Turkmenistan advocated a model that ignored the existence of the Absheron Peninsula.”14

On August 23, 1999, Azerbaijan presented a new proposal for founding a joint Azerbaijan-Turkmen company. According to that proposal, the new company would choose an investor for the exploitation and development of the Kyapaz oil field. However, there was no any reply from the Turkmenistan side concerning the proposal.15 In mid-2001, tension increased between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, resulting in the halting of diplomatic relations.16 Beginning from 2005, the dispute was triggered again with the approval of a plan by Turkmenistan for the exploitation of the Serdar/Kyapaz field by a Canadian company, Buried Hill Energy. This drew a strong reaction from the Azerbaijani side. SOCAR, the Azerbaijan state oil company, emphasized that the oilfield belonged to Azerbaijan and that it was going to develop it itself. Deputy Foreign Minister of Azerbaijan, Khalaf Khalafov, condemned Turkmenistan for its unilateral action in the Serdar/Kyapaz oil field.17

The relationship between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan seemed to normalize only in 2006. After being elected as president of Turkmenistan, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov began to look for an alternative way to solve the dispute. He reestablished the Inter-ministerial Commission of the Caspian Sea littoral states and reset diplomatic relations with Azerbaijan after his official visit to Baku in May 2008.18

However, while the efforts of the new President signaled Turkmenistan’s intention to return to the negotiation table to resolve the dispute, Berdymukhamedov claimed that it was the intention of his government to take Azerbaijan to International Arbitration.19 During the special governmental meeting on July 24, 2009, Berdymukhamedov underlined the development of the Azeri and Chirag fields by Azerbaijan and its claims to the Serdar/Kyapaz field, and instructed Vice Premier Rashid Meredov to investigate the legality of the Azerbaijani operation in the disputed territory.20 Furthermore, he declared that, “We [Turkmenistan] are ready to accept any decision of an international court.”21

During his interview on July 27, 2009, Khalaf Khalafov, Deputy Foreign Minister of the Azerbaijan Republic, stated that Azerbaijan was ready to defend its interests in the Caspian Sea oil field dispute

Berdymukhamedov’s statement took Azerbaijan by surprise, because only a few days prior to the president’s statement, official representatives of both countries had finished their discussions regarding the legal division of the Sea. No progress was registered for the solution of the dispute during the discussion; however, the Turkmenistan side had not expressed any disagreement and had mentioned nothing about arbitration.22 During his interview on July 27, 2009, Khalaf Khalafov, Deputy Foreign Minister of the Azerbaijan Republic, stated that Azerbaijan was ready to defend its interests in the Caspian Sea oil field dispute. He remarked, “As early as the early 1990s, Azerbaijan conducted detailed research concerning these fields and our position now is fully legal.”23 The legality of the Turkmenistan president’s statement is itself questionable; because Berdymukhamedov never stated which international court he was referring to. According to Alexander Jackson, there are various international courts that deal with arbitration, such as the London Court of International Arbitration, the ICC International Court of Arbitration in Paris, and the Stockholm International Arbitration Court. However, these courts mainly work on issues of contract implementation. The delimitation of sea borders is dealt with by the International Court of Justice in the Hague. In order to take Azerbaijan to the International Court of Justice, both countries would have to recognize its jurisdiction.24 As Cornel emphasizes: “...there was no arbitration court whose jurisdiction had been accepted by both countries.”25 Moreover, even if Turkmenistan did have a right to take Azerbaijan to the International Court of Justice, the consequence would likely be favorable for Azerbaijan. As Alexander Jackson indicates, “Azerbaijan seems confident that in case of any international adjudication the court will find in its favor, particularly over Azeri and Chirag, which lie not far from its Absheron Peninsula.”26

Rasim Musabekov, a political analyst in Baku, said that Azerbaijan could use the Turkmenistan President’s statement to its own advantage: “seeking arbitration is better that than endlessly keeping the problem unresolved, poisoning bilateral relations, blocking cooperation and letting third countries play off the existing hostility.”27 He added, “If there is no way to solve [the dispute] by bilateral talks and Ashgabat wants to appeal to international arbitration; I see no reason why Baku should be against that.”28 According to Rustam Mammadov, Turkmenistan’s statements “are groundless;” “Azerbaijan enjoyed the right to these fields under the USSR, and, in the case of the Caspian Sea, the standard legal principle applies: The owner is [that country] which owned it before.”29 He added that, “Turkmenistan will ruin the negotiations on the legal status of the Caspian Sea and will not gain anything from this appeal. There are no normative acts on this problem and the dispute should be resolved based on mutual agreement and trust.”30

The willingness of Turkmenistan to take Azerbaijan to court also risked the future of the Azerbaijan-Turkmenistan relationship and negotiations on the construction of the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline. Accordingly, the position of Turkmenistan was serving to the interests of Russia, which was trying to stop the construction of the pipeline. Nevertheless, after the gas crisis between Turkmenistan and Russia in 2009, Turkmenistan again turned toward the West and in October 2009 declared an annihilation of its call for international arbitration.31 According to the Neutral Turkmenistan newspaper report, Berdymukhamedov said that his statement that we are ready to accept any decision of the court “clearly marked [Turkmenistan’s] goodwill to eliminate any misunderstanding between the bordering countries.” Berdymukhamedov added that for Turkmenistan to solve the legal problem of the Caspian Sea in general was more important than arguing about the ownership of separate geographical areas.32

Thus, it was widely believed that the resolution of the dispute mainly depended on the signing of the Convention on the new status of the Caspian Sea, rather than on international arbitration that was unlikely to materialize.

Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea

With the break-up of the Soviet Union, the coastal states of the Caspian Sea increased from two to five, which changed the political situation of the Sea and pushed the newly independent states into conflict over its legal status due to its immense offshore hydrocarbon resources and its geographical position over an important transport route. The transformation of the political geography of the Sea divided the coastal states into two groups: Russia and Iran on one side and the newly independent states on the other, each side holding different views on the delimitation of the Sea.

The Russian-Iran alliance argued that before the dissolution of Soviet Union, the Caspian Sea was under the control of Russia and Iran in accordance with the treaties of 1921 and 1940. They claimed that according to the Alma-Ata Declaration of December 21, 1991 on the dissolution of the Soviet Union, all former republics of the Union and littoral states of the Caspian Sea should recognize the validity of the international agreements signed by the Soviet Union, including the treaties of 1921 and 1940.

It should be mentioned that the Treaty on Friendship and Cooperation between Iran and Soviet Russia had been signed on February 26, 1921.33 Article 11 of this treaty gave an equal, free-floating right to the parties under their flags. According to Article 7 of the treaty, the entrance of any other countries to the Sea was prohibited.34 The treaty of 1940, titled “Commerce and Navigation,” reiterated the provision of the commercial and fishing rights of the parties and claimed that the ships that belonged to these countries had navigation rights in the Sea.35 Therefore, Russia and Iran argued that the Caspian should be regulated according to the condominium principle, that the United Nation Convention of the Law of the Sea of 1982 is not applicable to the Caspian Sea issue and that the treaties that mentioned above “should serve as the legal basis for the rights and obligations of all littoral states in the Caspian Sea.”36

The delimitation of sea borders is dealt with by the International Court of Justice in the Hague. In order to take Azerbaijan to the International Court of Justice, both countries would have to recognize its jurisdiction

By supporting the condominium principle, Russia was trying to preserve its former status over the former Soviet Republics of the Caspian Sea and not allow any foreign power to enter its sphere of influence. To benefit from the huge hydrocarbon resources of these countries was another priority of Russia’s Caspian policy. Russia opposed the application of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to the Caspian and its division according to national sectors. It insisted on considering the Caspian as the common property of the coastal states according to the Soviet-Iran treaties and the establishment of joint ownership in the Sea, and refused to permit unilateral exploration of the Sea by any littoral state without the consent of the other Caspian states.37 Iran was aware that if the Caspian Sea was going to be divided into national sectors, its portion would be at maximum 14 percent and it would lose its claims to the oil fields situated on the median line between Iran and Azerbaijan. Therefore, it began to support the division of the Sea into five equal parts, giving 20 percent to each country, which is the position that Iran defends to this today.38

However, the newly independent coastal states of the Caspian Sea raised a question about the legality of the above-mentioned treaties. According to them, these treaties had never addressed the exploitations of the seabed of the Caspian,39 never defined the legal status of the Sea and dealt with only fishing and navigation.40 In this respect, while adopting UNCLOS, they were in favor of the division of the Sea according to the national sectors of each country.41 They argued that if the provisions of UNCLOS are not applicable to the division of the Caspian Sea, it should be determined as a boundary lake.42

1997 was a turning point in the dispute over the Caspian Sea. From that time on, some of the littoral states came to an agreement regarding the exploitation and development of the hydrocarbon resources of the Sea. The first countries to come to agreement were Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, followed by the deal between Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. They agreed to divide the Sea along the median lines.43 In 1998, a deal was reached between Russia and Kazakhstan for the division of the seabed of the north part of Sea and leaving the surface for common use.44 According to Jeffrey Mankoff, Russia completely relinquished its previous position because it had discovered immense hydrocarbon resources in its sector of the Caspian Sea; if it had kept insisting on applying the condominium principle to the division of the Sea, then other littoral states would have had a share in the hydrocarbon resources in its northern Caspian sector.45 With the election of Vladimir Putin as president of Russia in 2000, Russia began to follow a more active role in Caspian Sea issues. The intention of the new Russian provision on the legal status of the Caspian was to solve problems gradually; first, focus on the ecological and navigation problems, then solve the dispute between the southern coastal states regarding the offshore fields situated on the median line and as a final stage come to a conclusion on the Caspian Sea’s legal status.46

After Putin’s election, relations between Azerbaijan and Russia also entered into a new sphere with the mutual official visits of the presidents to each country. During Putin’s visit to Azerbaijan on January 9, 2001 the parties came to agreement on the division of the seabed along the median line principle, leaving the sea surface for common use.47

According to Rovshan Ibrahimov, there were several reasons for Russia to insist on the division of the seabed into national sectors but to keep the surface for the common usage of the littoral states. First, the northern part of the Caspian Sea is not convenient for fishing due to the weather conditions. Second, Russia was aware that division of the surface would make it available for the Central Asian energy-exporting countries of the Caspian to construct a Trans-Caspian Pipeline to transport their hydrocarbon resources to European markets, bypassing Russia and decreasing its monopoly over the transportation routes. Finally, Russia had concerns about the increasing interests of Western countries and organizations, especially the U.S. and NATO, in the region. The division of the surface into national sectors would make it easier for NATO to deploy its military ships into the Caspian Sea, which Russia considered a direct threat to its interests.48

Thus, following the positive developments on the Caspian Sea issue between the northern littoral states, in May 2003, Russia, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan signed an agreement for the delimitation of the Sea into their adjacent sectors.49 According to the agreement, 64 percent of the northern Caspian was divided into national sectors of the three republics according to the median line principle, which gave Kazakhstan 27 percent, Russia 19 percent, and Azerbaijan 18 percent.50

Russia opposed the application of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to the Caspian and its division according to national sectors

The bilateral negotiations between Iran and Azerbaijan did not conclude with a positive outcome. During his visit to Iran in 2002, President Heydar Aliev proposed the joint exploration and development the oil fields over which they had had a military confrontation in July 2001. However, the proposal was rejected by Iran. Afterward, several bilateral talks took place between Iran and Azerbaijan until the end of 2002 without any progress. Iran and Turkmenistan did not accept the partition of the northern Caspian among Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Iran insisted on giving an equal share to all five states. Therefore, the two southern Caspian countries, Iran and Turkmenistan joined in an alliance against the northerners.51

The dispute between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan is another case that has not been resolved up until now. The sides came to a decision to divide the Sea according to the median line principle, but could not agree upon the point from which the median line should be calculated. Turkmenistan insisted on measuring the line from mainland Azerbaijan, ignoring the Absheron Peninsula, the natural territorial intervention of Azerbaijan into the Caspian Sea. If this coordinate were accepted, not only the disputed field Serdar/Kyapaz, but also the Azeri and Chirag oil fields that had been developed by an international consortium since 1994, would fall into Turkmenistan’s sector of the Caspian Sea. Logically, this provision was not accepted by Azerbaijan.

In this regard, Caspian summits were considered the main platforms where the parties discussed their disagreements and searched for a final decision on the status of the Sea. Prior to the Convention of 2018, four summits of the heads of littoral states were held in 2002, 2007, 2010, and 2014.

The first summit of the heads of littoral states of the Caspian Sea took place in 2002 in Turkmenistan. However, the summit failed to achieve any important step toward determining the legal status of the Caspian Sea and ended without any progress. On the contrary, it triggered tension among the littoral states, especially between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. The situation is clarified by President Saparmurad Niyazov as “the Caspian Sea is smelling of blood and each of us must realize it. It is not an easy thing to have a dispute over an oil field.”52

The second summit of Caspian Sea heads of state was held in 2007 in Tehran. While the summit registered no progress and failed to resolve the legal status of the Sea, the parties concluded the summit with a joint declaration called the Tehran Declaration, ratified as the first political document by the heads of the Caspian Sea countries.53

At the third summit, held in 2010 in Baku, the leaders of the five littoral states of the Caspian Sea signed an agreement on security cooperation, which was one of the main points of the summit’s agenda. According to that agreement, only the littoral states are responsible for the security and protection of the Sea. The reason for the security agreement was the militarization of the littoral states.54

At the fourth summit held in 2014 in Astrakhan, the littoral states made significant progress in their talks and agreed on the following issues: emergency prevention and response, hydrometeorology and the preservation and rational use of biological resources of the Sea.55 In addition, the parties agreed that each of them would control an area 15 nautical miles from their shore and enjoy exclusive fishing rights up to 25 miles; they would consider mutual security concerns in terms of military presence, and would ensconce mutual trust and respect for mutual interests as the main principles of the talks. Although these decisions were only considered recommendations, they played a guiding role in the preparation of the final draft of a new Convention on the status of the Caspian Sea.

The parties reached a final agreement in 2018 at the fifth summit of the Caspian heads of state in Aktau and signed a new Convention on the Status of the Caspian Sea. The Convention reserves all rights over the Caspian Sea and its resources to the five coastal States.56 From this perspective, the littoral states define the Caspian as a “peace” sea, and prohibit the access of non-littoral military forces to the basin. This part in particular was important for Russia and Iran, whose governments remained concerned about the possible military participation of Western countries in the region. The legal status of the waters, the seabed and the subsoil, demarcation, natural resources, fisheries and navigation are the main issues covered in the new Convention. According to Article 5 of the Convention, the Caspian Sea is divided into internal waters, territorial waters, fishery zones, and common maritime space. The new status of the Caspian Sea provides the littoral states with sovereignty over their “land territory and internal waters to the adjacent sea belt called territorial waters, as well as to the seabed and subsoil thereof, and the airspace over it”.57 Article 7 determines the limits of the territorial waters, which should not exceed 15 nautical miles measured from baselines determined in accordance with the Convention. The Convention does not delimit the internal and territorial waters between the states, leaving that to the bilateral and multilateral agreements of the states.

Article 14 of the Convention provides the right to littoral states to lay submarine cables and pipelines on the seabed: “Submarine cables and pipeline routes shall be determined by agreement with the Party the seabed sector of which is to be crossed by the cable or pipeline.” Thus, the countries do not need approval from all of the littoral states to construct a pipeline on the seabed in their area of the Caspian Sea. Article 15 demands that the littoral states preserve the ecological system of the Caspian Sea, and gives the right to other coastal countries individually or jointly to monitor environmental processes in the territorial sectors of other littoral states.

Thus, the new Convention of the Caspian Sea has resolved some of the long-lasting problems between the littoral states; however, the resolutions of others are not clear enough in the text of the Convention. Thus, they need further interpretation to understand the extent to which the Convention solves disagreements between the littoral states, particularly between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

The division of the surface into national sectors would make it easier for NATO to deploy its military ships into the Caspian Sea, which Russia considered a direct threat to its interests

Unresolved Issues

Contrary to expectations, the Convention does not resolve the disputed issue of delimitation between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan. While the Convention does divide the seabed into national sectors, it doesn’t provide a common formula for the delimitation of the seabed.58 Thus, “delimitation” itself remains unclear in the text of the Convention. The Convention authorizes coastal states to delimit the seabed according to bilateral and multilateral agreements with due regard to the generally recognized principles and norms of international law. Bilateral and trilateral agreements among Azerbaijan, Russia and Kazakhstan, and between Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan successfully resolved the delimitation of the seabed in the Northern Caspian sectors. Apparently, the agreement encourages Azerbaijan, Iran and Turkmenistan to use the Northern Caspian model to conclude bilateral agreements on delimitation of their sectors.

One of the main obstacles to solving the delimitation issue is Iran’s refusal to agree on the median line principle for delimiting the South Caspian sectors. After the signing the Convention in Aktau, Iranian President Hassan Rohani said that the Convention only solved 30 percent of the problems, and that the delimitation of the Caspian seabed would require additional agreements between the littoral states.59 Later, Russian Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Grigory Karasin stated that Moscow would prefer that Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan resolve disputes in a bilateral or trilateral manner, and not involve all five countries in the process.60

The Convention authorizes coastal states to delimit the seabed according to bilateral and multilateral agreements with due regard to the generally recognized principles and norms of international law

Another hindrance for reaching agreement on the delimitation issue is the disagreement between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. After the signing of the Convention, communication between the parties intensified further. The President of Turkmenistan made two official visits to Azerbaijan in 2018 and 2020; in those meetings, the parties mainly discussed transportation and energy projects. Particularly, after the exploitation of Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railways, Turkmenistan, which plans to become a regional transportation hub between the East and West, significantly increased its interest in developing relations with Azerbaijan. Although there is no document on the implementation of any substantial projects among the cooperation agreements concluded in Baku between Aliyev and Berdymukhamedov, the latter particularly noted the importance of the development of multidimensional energy cooperation between the parties.61 To attest to the importance of relations with Azerbaijan, on March 14 Berdymukhamedov approved the composition of the Turkmen-Azerbaijani Intergovernmental Commission on Economic Cooperation on the Turkmen side. At the same time, the Turkmen leader emphasized that both states have enormous resources, economic and transport-communication potential, the implementation of which meets not only the national interests of the two countries but also the goals of regional and global sustainable development.62

The intensification of relations between the parties has increased hopes for the resolution of the dispute over the delimitation of the Caspian seabed. Resolution of the delimitation problem is also important from the perspective of the realization of the TCP project.

An aerial view of a crude oil storage facility belonging to the CPC in the Krasnodar Territory, Russia, September 19, 2019. VITALY TIMKIV / Getty Images

An aerial view of a crude oil storage facility belonging to the CPC in the Krasnodar Territory, Russia, September 19, 2019. VITALY TIMKIV / Getty Images

Prospects for a Trans-Caspian Pipeline

The new Convention of the Caspian Sea allows Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan to construct pipeline on the seabed of their territorial waters without special approval from the other littoral states. After the signing of the Convention, the TCP project again began to be discussed by the interested parties. The EU is particularly interested in Turkmen gas, as it seeks to diversify its natural gas supply sources.63 In September 2011, the EU gave the European Commission a mandate for negotiations between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan regarding the legal framework of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline. The importance of the TCP was also stated in the “External Energy Relations of the European Union.” This document reflects the EU energy strategy until 2020, with 43 specific issues related to ensuring European energy security. Among the main, large-scale projects necessary for the implementation of energy security in Europe, the TCP was highlighted in the document.

For the EU, the issue of building a gas pipeline is essential because Azerbaijan completed the construction of the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) pipeline with the political and economic support of the Union, and work continues to complete the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). Under such circumstances, Turkmenistan could join this route by laying a pipeline along the bottom of the Caspian Sea.

The U.S. also supports the TCP project and is inspiring Turkmenistan to activate its initiatives in the realization of the project. U.S. President Donald Trump, in a congratulatory telegram to President Berdymukhamedov on the occasion of the Novruz holiday, expressed his hope that Turkmenistan would start using its opportunities to export gas to the West after the recent determination of the legal status of the Caspian Sea.64

While the EU and U.S. support the TCP, however, Russia and Iran oppose the implementation of the project. They argue that, according to the new Convention, countries have the right to construct a pipeline through the seabed of their territorial sector, but due to environmental concerns, the project needs to be discussed with all the littoral states. Behruz Namdari, a spokesperson for the National Iranian Gas Company, said that the construction of a gas pipeline from East to West could cause severe damage to the ecology of the region and that Iran opposes its realization.65 Namdari suggested that Baku and Ashgabat use Iranian infrastructure instead to transport gas to Europe. Simultaneous with the Iranian statement, Sergey Prikhodko, Deputy Head of the Apparatus of the Government of Russia, also made it clear that Russia is against the TCP project for environmental reasons.66

Although the new Convention indeed obliges parties to involve all littoral states in environmental monitoring before the construction of pipelines, the precise mechanisms for this monitoring are not mentioned in the main document. Article 12 of the Convention clearly states “submarine cables and pipelines routes shall be determined by agreement with the Party the seabed sector of which is to be crossed by the cable or pipeline.”67 In this regard, the statements of Iran and Russia are more political than environmental and ecological. Iran is currently considering the construction of a pipeline along the bottom of the Persian Gulf in Oman. An agreement on the construction of this gas pipeline was signed at the end of August 2015. In January of 2019, Iran announced its readiness to begin construction of the onshore section of the pipeline. For its part, Russia has completed the construction of Turk Stream across the bottom of the Black Sea, and the construction of Nord Stream 2 across the bottom of the Baltic Sea is continued. Indeed, all of those projects are more complex and more threatening to the environment than the proposed construction in the Caspian. Moreover, when two pipelines (one oil, one gas) leading from Kazakhstan’s offshore Kashagan site ruptured and leaked shortly after production started in September 2013, none of the littoral states took any action, or even voiced any criticism against Kazakhstan.68

Currently, the construction of the TCP mainly depends on Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. Even though Baku’s transit of Turkmenistan gas via the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) may be attractive to a certain extent, in terms of the rational use of its energy resources and transit revenues, Azerbaijan is aware of the future political risks of this project. The appearance of large volumes of Azerbaijani gas on the European market, together with Turkmenistan gas, may, in the future, significantly weaken Russian influence in European countries. Development of the process in that direction, in the end, may lead to the worsening of its relations with Russia, which the Azerbaijani government does not desire.

Further, Azerbaijan is not interested in investing in the TCP. It is estimated that $1.5 billion is required for the construction of the TCP, but none of the parties, including Turkmenistan, have expressed a wish to spend this amount of money. While the EU has expressed its support to Turkmenistan, Brussels has no specific plans for this project. No gas-producing company has shown any interest, or any signed documents. The statements of the White House, not supported by concrete actions, suggest that the TCP project is being used as a method of putting pressure on Russia.

The new Convention of the Caspian Sea allows Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan to construct pipeline on the seabed of their territorial waters without special approval from the other littoral states

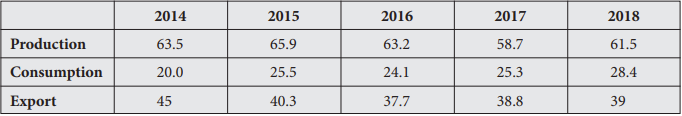

On its own, Turkmenistan does not have enough financial resources to implement this project. Further, while Turkmenistan’s recent natural internal gas consumption has increased, production has not. And, compared to previous years, exports have gradually decreased (Table 1). To make the TCP profitable, Turkmenistan would need to load it with an additional 30 billion cubic meters of gas. With 10 trillion cubic meters of proven gas reserves, Turkmenistan is the third-largest country in the world due to its gas resources; however, its infrastructure needs additional investments to increase production.

Table 1. Natural Gas in Turkmenistan (2014-2018, Billion Cubic Meters)

Under the circumstances, the potential for the realization of the TCP does not seem realistic. Why, then, has Turkmenistan recently begun to promote this project? In short, Turkmenistan appears to be using the increasing interest of the EU and the U.S. in the TCP to further its geopolitical interests. Indeed, the U.S. has activity forced Russia to take steps to resolve a gas dispute with Turkmenistan. Russian’s purchases of Turkmen gas had been discontinued since 2016, when Gazprom accused Turkmengas of a severe breach of contract.69

“Russia purchased only about 10 bcm from Turkmenistan in 2010, 2011 and 2012 – four times less than in 2008. In February 2015, Gazprom revealed that in that year it would import only two-fifths of the 10 bcm it had imported from Turkmenistan in 2014, noting that ‘there is no technological necessity for the purchase of foreign gas’. As of mid-2015, Gazprom had failed to pay any of its 2015 gas bills to Turkmenistan and in July it filed a case against Turkmengaz at the international arbitration court in Stockholm demanding a revision of prices”.70

Now there has been a return to long-term Russian-Turkmen gas cooperation – Ashgabat needs Russian equipment and materials to modernize and develop its gas transmission system, while Moscow jealously watches the activity of American diplomacy in Central Asia.

The Kremlin has already taken a step towards reconciliation with Ashgabat. Gazprom has already signed a five-year contract with Turkmengas for the purchase of 5.5 bcm per year. Thus, along China, Turkmenistan gas also began to be exported to Russia in April of 2019.71

While the EU has expressed its support to Turkmenistan, Brussels has no specific plans for this project. No gas-producing company has shown any interest, or any signed documents

Conclusion

Although the new Convention met with optimism in the littoral states of the Caspian Sea, it did not constitute a final agreement among the disputing parties. While the new Convention provided littoral states with sovereignty over their “land territory and internal waters to the adjacent sea belt called territorial waters, as well as to the seabed and subsoil thereof, and the airspace over it,” it didn’t delimit the internal and territorial waters between the states, leaving that matter to be resolved through bilateral and multilateral agreements. Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan agreed to delimit the Sea according to the median line principle, but they couldn’t agree about the point from which the median line should be calculated. Thus, the new Convention divides the seabed into national sectors, but it doesn’t provide a common formula for the delimitation of the seabed. Thus, this remains one of the most problematic issues between the parties. Therefore, rightly, the new Convention of 2018 was assumed to be a political decision rather than a legal proceeding for resolving the dispute over the legal status of the Caspian Sea. According to the Convention, the Caspian is defined as a “peace” sea, which excludes the access of non-littoral military forces to the basin, which was important for the powerful states of the Caspian Sea, particularly for Russia and Iran.

Regarding the construction of the TCP, the new Convention gives the parties the right to lay submarine cables and pipelines on the seabed without getting special approval from the other littoral states. However, the new Convention contradicts itself. It gives the right to other coastal countries to monitor environmental processes in the territorial sectors of other littoral states. Therefore, in light of the energy interests of the EU and U.S., Russia and Iran raised a question regarding the implementation of the TCP project. They argued that according to the new Convention, even though countries have the right to construct a pipeline through the seabed of their territorial sector, due to environmental concerns, the project needs to be discussed with all of the littoral states. Russia’s real concern is that the construction of the TCP for transporting Turkmenistan gas to Europe would bypass Russia and decrease its monopoly over the transportation routes of the Caspian region. Therefore, the statements of Russia and Iran are considered more political rather than environmental and ecological.

Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan agreed to delimit the Sea according to the median line principle, but they couldn’t agree about the point from which the median line should be calculated

Moreover, according to estimates for the construction of the TCP, $1.5 billion is required. However, neither Azerbaijan nor Turkmenistan are interested in investing in this project. Of course, the EU has expressed its support to Turkmenistan, but Brussels has no specific plans for this project. As for the U.S., the White House did not support the project with any concrete actions. Thus, the construction of the TCP is not only dependent on the consent of Russia and Iran, but also on the will of Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan and the political and financial support of the EU and the U.S.

Endnotes

1. Zeinolabedin, M. S. Yahyapoor and Z. Shirzad, “The Geopolitics of Energy in the Caspian Basin,” International Journal of Environmental Research, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2011), p. 504.

2. Yusin Lee, “Toward a New International Regime for the Caspian Sea,” Problems of Post- Communism, 52, No. 3 (2005), p. 39.

3. Shamkhal Abilov, “Legal Status of the Caspian,” Caspian Report, (2013), p. 131.

4. Mustafa Aydın, “Oil, Pipelines and Security: The Geopolitics of the Caspian Region,” in Moshe Gammer (ed.), The Caspian Region Volume 1: A Re-Emerging Region, (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 9.

5. Ali Granmayeh, “Legal History of the Caspian Sea,” in Shirin Akıner (ed.), The Caspian: Politics, Energy and Security, (London: Routledge Curzon, 2004), pp. 16-17.

6. Faraz Sanei, “The Caspian Sea Legal Regime, Pipeline Diplomacy, and the Prospects for Iran’s Isolation from the Oil and Gas Frenzy: Reconciling Tehran’s Legal Options with Its Geopolitical Realities,” Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 34, No. 681 (2001).

7. Suleyman Sırrı Terzioğlu, “Hazar’ın Statüsü Hakkında Kıyıdaş Devletlerin Hukuksal Görüşleri,” Journal of Central Asian and Caucasian Studies, 3, No. 5 (2008), p. 42

8. Mahmoud Ghafouri, “The Caspian Sea: Rivalry and Cooperation,” Middle East Policy, 15, No. 2 (2008), p. 88.

9. Mustafa Aydın, “New Geopolitics of Central Asia and the Caucasus: Causes of Instability and Predicament,” SAM Paper, (2000), p. 23.

10. Lee, “Toward a New International Regime for the Caspian Sea,” p. 41.

11. İsmail Hakkı İşcan, “Caspian Region Energy Economics in Terms of International Energy Security and Caspian Sea Sharing Problem,” Sosyoekonomi, 6, No 12 (2010), pp. 70-71.

12. Granmayeh, “Legal History of the Caspian Sea,” p. 22.

13. Khagani Malikov, “Geopolitical Challenges and Legal Issues in the Caspian Sea Basin,” The Journal of the Study of Modern Society and Culture, 40 (2007), p. 229.

14. Svante E. Cornell, Azerbaijan Since Independence, (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2011), p. 223.

15. Granmayeh, “Legal History of the Caspian Sea,” p. 23.

16. Mehrdad Haghayeghi, “The Coming of Conflict to the Caspian Sea,” Problems of Post-Communism, 50, No. 3 (2003), p. 32.

17. Lee, “Toward a New International Regime for the Caspian Sea,” p. 45.

18. Marlene Laruelle and Sebastien Peyrouse, “The Militarization of the Caspian Sea: “Great Games” and “Small Games” Over the Caspian Fleets,” China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, 7, No. 2 (2009), p. 22.

19. Fariz Ismailzade, “Turkmenistan’s Initiatives Upset Caspian Balance,” The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, (2009).

20. Anar Valiyev, “Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan’s Dispute over the Caspian Sea: Will It Impede the Nabucco Project?,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, 87, (2009), p. 1.

21. Matt Stone, “Turkmenistan Warms up to Caspian Delimitation Deal with Baku,” ADA Biweekly Newsletter, 3, No. 20 (2010), p. 4.

22. Alexander Jackson, “The Implications of the Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan Dispute,” Caucasian Review of International Affairs (CRIA), 42, (2009).

23. Shahin Abbasov, “Azerbaijan: No Jitters Over Turkmenistan’s Caspian Sea Threat,” EURASIANET, (July 29, 2009), retrieved May 20, 2020 from https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-no-jitters-over-turkmenistans-caspian-sea-threat.

24. Jackson, “The Implications of the Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan Dispute.”

25. Cornell, Azerbaijan Since Independence, p. 224.

26. Jackson, “The Implications of the Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan Dispute.”

27. Abbasov, “Azerbaijan: No Jitters Over Turkmenistan’s Caspian Sea Threat.”

28. Abbasov, “Azerbaijan: No Jitters Over Turkmenistan’s Caspian Sea Threat.”

29. Abbasov, “Azerbaijan: No Jitters Over Turkmenistan’s Caspian Sea Threat.”

30. Fariz Ismailzade, “Baku Surprised by Berdimuhamedov’s Inflammatory Statement,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 6, No. 151 (2009).

31. Stone, “Turkmenistan Warms up to Caspian Delimitation Deal with Baku,” p. 4.

32. Hasanov, “It Is Important to Solve Legal Problem in Caspian, Rather than Argue about Separate Geographical Facilities: Turkmen President,” Trend News Agency, (October 2, 2009), retrieved May 20, 2020 from https://en.trend.az/business/energy/1551444.html.

33. Seyyed Rasoul Mousavi, “The Future of the Caspian Sea after Tehran Summit,” The Iranian Journal of International Affairs, 21, No. 1-2 (2008-2009), pp. 28-29.

34. Rustam F. Mamedov, “International-Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in its Historical Development,” The Turkish Yearbook, Vol. 30, (2000), p. 123.

35. Sohbet Karbuz, “The Caspian’s Unsettled Legal Framework: Energy Security Implications,” Journal of Energy Security, (May 18, 2010), retrieved May 20, 2020 from http://www.ensec.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=244:the-caspians-unsettled-legal-framework-energy-security-implications&catid=106:energysecuritycontent0510&Itemid=361.

36. Granmayeh, “Legal History of the Caspian Sea,” p. 16.

37. Rustam Mamedov, “International Legal Status of the Caspian Sea: Issues of Theory and Practice,”

The Turkish Yearbook, 32, (2001), p. 231.

38. Adam Dempsey, “Caspian Sea Basin: Part 4 - Is It a Sea or Is It a Lake?” Defense Viewpoints, (October 2, 2009), retrieved May 20, 2020 from https://www.defenceviewpoints.co.uk/articles-and-analysis/caspian-sea-basin-part-4-is-it-a-sea-or-is-it-a-lake.

39. Haghayeghi, “The Coming of Conflict to the Caspian Sea,” p. 34.

40. Aydin, “Oil, Pipelines and Security,” p. 9.

41. Munir Ladaa, Transboundary Issues on the Caspian Sea Opportunities for Cooperation, (Bonn: BICC, 2005), p. 11.

42. Lee, “Toward a New International Regime for the Caspian Sea,” p. 39.

43. Haghayeghi, “The Coming of Conflict to the Caspian Sea,” pp. 35-36.

44. Ladaa, Transboundary Issues on the Caspian Sea Opportunities for Cooperation, 12.

45. Interview with Jeffrey Mankoff, Baku, May 28, 2013.

46. Mamedov, “International Legal Status of the Caspian Sea,” p. 246.

47. John Roberts, “Energy Reserves, Pipeline Routes and the Legal Regime in the Caspian Sea,” in Gennady Ghufrin (ed.), The Security of the Caspian Sea Region, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 67.

48. Interview with Rovshan Ibrahimov, Baku, July 15, 2013.

49. Robert M. Cutler, “Turkmenistan and Iran Drop Legal Bombshells at Caspian Sea Summit,” Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, 12, No. 23 (2010), p. 4.

50. Jeronim Perovic, “From Disengagement to Active Economic Competition: Russia’s Return to the South Caucasus and Central Asia,” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 13, No. 1 (2005), pp. 68-69.

51. Lee, “Toward a New International Regime for the Caspian Sea,” p. 44.

52. Haghayeghi, “The Coming of Conflict to the Caspian Sea,” p. 32.

53. Mousavi, “The Future of the Caspian Sea after Tehran Summit,” pp. 37-38.

54. Sergei Blagov, “Moscow Aims for Caspian Settlement in 2011,” Eurasian Daily Monitor, 7, No. 216 (December 3, 2010), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://jamestown.org/program/moscow-aims-for-caspian-settlement-in-2011/.

55. Nicola Contessi, “Traditional Security in Eurasia,” The RUSI Journal, 160, No. 2 (2015).

56. “The Caspian Sea Treaty,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 24, No. 9 (2018).

57. “Article 6,” Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, August 12, 2018.

58. Rizal Abdul Kadir, “Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea,” International Legal Materials, 58, No. 2 (2019).

59. “Five States Sign Convention on Caspian Legal Status,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, (August 12, 2018), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-iran-azerbaijan-kazakhstan-turkmenistan-caspian-sea-sum- mit/29428300.html.

60. Ilham Shaban, “Under New Convention, Caspian Not to Be Sea or Lake,” Caspian Barrel, (August 10, 2018), retrieved May 21, 2020 from http://caspianbarrel.org/en/2018/08/under-new-convention-caspian-not-to-be-sea-or-lake/.

61. “Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan Seek to Develop Trade Ties and Transportation Corridor,” Silk Road Briefing, (March 31, 2020), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2020/03/31/azerbaijan-turkmenistan-seek-develop-trade-ties-transport-corridors/.

62. “Turkmen Composition Intergovernmental Commission on Economic Cooperation with Azerbaijan Approved,” Trend News Agency, (March 16, 2020), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://en.trend.az/casia/turkmenistan/3208307.html.

63. Fakhri J. Hasanova, Ceyhun Mahmudlud, Kaushik Deba, Shamkhal Abilov, and Orkhan Hasanov, “The Role of Azeri Natural Gas in Meeting European Union Energy Security Needs,” Energy Strategy Reviews, 28, No. 100464 (2020).

64. “Turkmenistan: The Trump Card,” org, (March 26, 2019), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://eurasianet.org/turkmenistan-the-trump-card.

65. Azad Garibov, “Hopes Reemerge for Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline, but Critical Obstacles Persist,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 16, No. 118 (2019).

66. “Critical Attitude of Moscow and Tehran to Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline Remains,” az, (August 13, 2019), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://www.turan.az/ext/news/2019/8/free/politics%20news/en/83013.htm.

67. “Article 12,” Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, August 12, 2018.

68. Bruce Pannier, “A Landmark Caspian Agreement: And What It Resolves,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, (August 9, 2018), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-landmark-caspian-agreement--and-what-it-resolves/29424824.html.

69. “Gazprom Broke the Contract with the State Concern Turkmengaz for Serious Violations,” Center for Strategic Assessment and Forecasts, (March 15, 2016), retrieved May 21, 2020 from http://csef.ru/en/ekonomika-i-finansy/431/gazprom-razorval-kontrakt-s-turkmengazom-iz-za-sereznogo-narusheniya-6617.

70. Annette Bohr, “Turkmenistan: Power, Politics, and Petro-Authoritarianism,” Chatham House, (March 8, 2016), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2016-03-08-turkmenistan-bohr.pdf.

71. “Gazprom Signs Five-Year Natural Gas Contract with Turkmenistan,” Reuters, (July 3, 2019), retrieved May 21, 2020 from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-gazprom-turkmenistan-deal/gazprom-signs-five-year-natural-gas-contract-with-turkmenistan-idUSKCN1TY1X5.