Introduction

The Trump Administration was characterized by its indifference to collective actions in exchange for a greater focus on bilateral relations. The former U.S. president was deemed ‘unpredictable’ in his foreign policy, as he marginalized the role of NATO and international organizations in managing various issues; the Eastern Mediterranean was no exception. In this article, we aim to study the Biden Administration’s main foreign policy objectives toward the Eastern Mediterranean by conducting a content analysis of his speeches and articles, within the framework of the multilateral approach he said he would follow, which includes working with allies in order to strengthen democracy around the world as a central tenet of his foreign policy approach. Biden is also expected to use ‘human rights’ as a tool with which to prod his rivals in the wider context of emerging powers in the region and the new competition over influence and energy resources.

We can trace another main pillar of Biden’s foreign policy doctrine in his rhetoric, that of restoring American leadership, which implies that Biden may use hard power as a tool to deter adversaries; he has stated that he wants to end ‘forever wars’ and be ‘smarter and stronger’ by maintaining smaller-scale missions while using diplomacy as the first instrument of American power.2 Biden also promised to keep NATO’s military capabilities sharp, calling on all NATO nations to recommit to their responsibilities as members of a democratic alliance.3

In forecasting Biden’s paths and the different scenarios that may unfold as he deals with these issues, we will try to answer a number of questions, among them: What is the main American grand strategy toward the Eastern Mediterranean region? To what extent can a multilateral approach affect the path of events in this area? And how will Biden Administration use his ‘smart and strong’ approach to deal with a more assertive Turkey when it comes to protecting national security in the region?

Losing potential buyers of its military hardware within its alliance is no less dangerous than allowing Russia to manipulate the energy security of its European allies

U.S. Grand Strategy Toward the Eastern Mediterranean

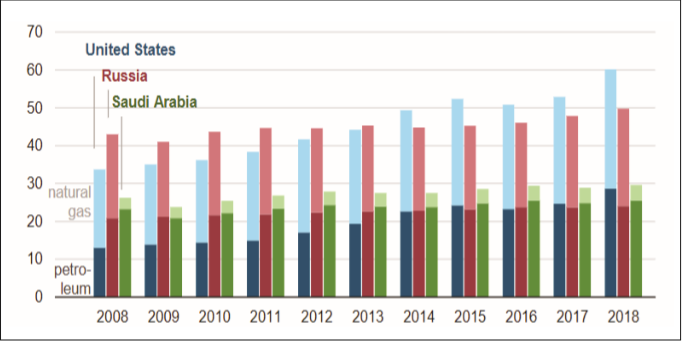

In analyzing the expected American strategy in Biden’s era in the Eastern Mediterranean, we have to keep in mind a very important transformation in the international energy landscape, namely that the U.S. has been the foremost producer of energy in the world since 2018; hence, the U.S. has become more of a competitor and a stakeholder than an honest broker and leader of an alliance, although preserving its pattern of alliances still among its top priorities, especially given the more assertive Russian defense and foreign policies toward the region. Losing potential buyers of its military hardware within its alliance is no less dangerous than allowing Russia to manipulate the energy security of its European allies. Nevertheless, being less dependent on foreign energy resources, the U.S. has been able to develop a more relaxed attitude toward the escalating crisis between Turkey and its neighbors in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Graph 1: Estimated Petroleum and Natural Gas Production in Selected Countries (2008-2018, Quadrillion Btu)

Turkey has been a cornerstone of the American strategy to contain Russia since the time of the famed Truman Doctrine. Indeed, both Turkey and Greece are pillars of this policy, so resolving their escalating dispute rather than marking Turkey as a rouge state fits more neatly with Biden’s doctrine of reviving NATO, implementing multilateralism, and working with allies. In this respect, we can identify the main U.S. strategy objectives in this region of the world today: containing Russia;5 ensuring energy security for U.S. allies in Europe; avoiding the militarization of regional disputes; keeping Turkey in the Western flank; fostering the newly formed alliance between Greece, Cyprus, and Israel;6 and having a stake in the lucrative European energy market.

The U.S. is also using its giant oil companies ExxonMobil and Noble Energy in order to assure its presence in the region, as it too is drilling for gas in the area and taking a share in its contracts, while preserving its presence in order to uphold the energy alliance between Israel, Greece, and Cyprus, with the help of other European companies, as a new arc of energy in the Eastern Mediterranean.7

Eastern and Southern Europe remain crucial to the U.S.’ Russian containment policy. After the discovery of shale gas reserves in the U.S., the Balkans and energy-poor regions in Europe became a priority for the U.S. energy industry, as the U.S. became the world’s largest energy provider, surpassing Russia and Qatar.8 Although the U.S. warns against the militarization of conflicts in the area, Washington relies on weapons exports as a major economic and military dominance policy, and in the wake of Russia’s deployment of S-400 missiles in Syria and Turkey’s purchase of this system, the U.S. is assisting its Greek and Israeli allies with military hardware and bases and is even increasing its own presence in the region. For the first time since 2016, the U.S. Navy recently deployed two Nimitz-class aircraft carriers to the region in April 2019.9

American mediation is urgently needed in Biden’s era, as bringing the different parties to the negotiation table will mark a return of American leadership and thus fulfill one of the main pillars of Biden’s foreign policy

Some speculate that the U.S. is fortifying its alliance with Turkey’s rival, Greece, to force Ankara to the negotiation table, as U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo signed a protocol of amendment to the Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement (MDCA) between Greece and the U.S., in October 2019, which relates to the use of Souda Base in Crete, the airbases of Stefanovikeio and Larissa in central Greece and the port of Alexandroupolis.10

The U.S. is trying to prove by this move that it can bypass Turkey’s İncirlik airbase and the Bosporus Strait by sending military hardware to its advanced military base in Romania, which is considered vital to confronting Russia there. The expansion of the Alexandroupolis port base is an indication that America is strengthening its alliance with Turkey’s rival Greece, with which Turkey has engaged in a sea demarcation conflict and which, with the aid of Egypt, is establishing a new alliance with Turkey’s rivals Greek Cyprus and Israel.

Nevertheless, one of the U.S.’s main objectives in the region is to restore Turkey as an ally and re-anchor Turkey with the West; the U.S. also aims to actively engage Turkey to positively form a stable, post-Syrian conflict environment and to hedge the further decline of U.S.-Turkey relations by creating complementary military basing rights and assets.11

Non-Escalation as a Prime Objective

Many analysts expect that Biden’s first priorities will emphasize domestic issues and focus on restoring democracy at home, guarantee economic stimulus for COVID-19 and revitalize U.S. infrastructure in the first days of his term, with foreign policy taking at least a temporary backseat to domestic challenges. In foreign policy, the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean region may not be Biden’s primary priority, as other areas, such as the Indo-Pacific, China, Europe, the Americas, and the renewal of transatlantic relations all require attention.

The Trump Administration had called for non-escalation from all parties in the region, in the context of the growing conflict between Turkey and Greece regarding the demarcation of maritime borders, and refrained from imposing harsh sanctions against Turkey. Then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in his visit to Greece on October 6, 2019, “Militarization of these conflicts is not the right direction to go.”12 For its part, Turkey is insisting on the continuation of drilling, which it sees as a lawful process, and it has deployed its navy in areas that are deemed contested.13

But the window of time is closing, and while Turkey continues gas exploration in disputed areas, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, President of the Republic of Turkey, says his country expects to open a new page regarding maritime demarcations and S-400 issues, urging Europe to “get rid of its strategic blindness,”14 as further delaying open negotiations will mean increasing the odds of confrontation in the Eastern Mediterranean. In the absence of U.S. leadership during the Trump era, France took more assertive actions against Turkey in support of EU member states Greece and Cyprus, in the context of a broader rivalry between Paris and Ankara over a number of regional issues. This eventually forced Turkey to expand its reach in the region by making an alliance with the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) on the demarcation of their maritime borders, a move that was viewed as a retaliation against the containment efforts led by members of the EastMed Gas Forum to isolate Ankara.

Clearly, American mediation is urgently needed in Biden’s era, as bringing the different parties to the negotiation table will mark a return of American leadership and thus fulfill one of the main pillars of Biden’s foreign policy. Failing to address the demarcation issue and establish the Turkish maritime border in the Mediterranean may lead to more assertive action from Turkey, which has reiterated its sovereign right to a share of the Mediterranean energy wealth, as well as its right of exploration.

Working with Allies on Economic Sanctions

EU leaders decided to place sanctions on an unspecified number of Turkish officials and organizations engaged in gas exploration in Cypriot-claimed waters, but postponed larger decisions such as trade tariffs or an arms embargo before consultation with the forthcoming Biden Administration.15 The Trump Administration had already imposed sanctions on Turkey’s Defense Industries and four of its top officials over Ankara’s purchase of Russian missile defenses.16

It is expected that Biden may threaten Ankara with further economic sanctions in order to force Turkey to accept certain outcomes of negotiations, either regarding the demarcation issue or the purchase of Russian weaponry systems, as Turkey is struggling to preserve the value of its currency and to resist collateral damages from the COVID-19 impact on its economy. But when it comes to Turkey’s national security issues, it would be a dangerous gambit to force an unwanted resolution of the conflict over the interests of Turkey, which might make it lean more to the Russian side, despite the difficulty of that move.

Losing Turkey from the Western alliance would be very costly for both sides. America would lose a cornerstone of this alliance, given the weight of the Turkish military in NATO, and Turkey’s entire air force combat squadron was either made by the U.S. or was flying with American supplies; more than half of its tanks’ armament and half of the navy’s combat fleet are made by the U.S., and the rest are sourced from Germany and other Western manufacturers.17

Imposing more sanctions on Turkey would definitely mark the end of its membership in the Western alliance; the effect of harsh sanctions on Turkey’s economy would make Ankara retaliate by boycotting Western-made products, as President Erdoğan has warned. Such contingencies would lead to an infinite escalation that would end by reshaping the whole pattern of alliances in the Middle East for years to come, and hence negatively affecting American leadership in the region, as the sanctions imposed by the Trump Administration were said also to be a warning for Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan.

America is very eager to prevent the emergence of an alliance led by Russia and China with most of the Muslim world, as it would force the major powers of these countries to rely on non-Western weapons and ultimately lead to the erosion of the American leadership of the current world order. That is why the Trump Administration was very reluctant to impose sanctions on Turkey, and ended up with trivial sanctions as a way to convince Turkey to negotiate.

Preserving an Energy Foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean

The U.S. is using its major oil companies to benefit from the newfound gas in the Eastern Mediterranean region, as both ExxonMobil and Noble Energy are drilling for gas and oil in the fields of Cyprus and Israel, along with other international companies from France, Britain, Italy, Russia, Qatar, and Israel.18 Noble Energy has a 70 percent share of Cyprus’s Aphrodite well, 39.66 percent of Israel’s Leviathan well, and 36 percent of Israel’s Tamar,19 as the U.S. is using its sophisticated technology in the deepwater search for hydrocarbons in the region as a tool for the mutual benefit of itself and its allies, and as leverage for its alliance in the region (Map 1).

Map 1: Companies Working in the Cyprus Gas Field in the Eastern Mediterranean (2017)

Some observers have expressed optimism that the newfound hydrocarbon wealth of the Eastern Mediterranean could work as a catalyst for peace and integration rather than an impetus for military escalation

Preserving a foothold in the region means guarantying non-escalation between the different parties, as this consortium of companies means an internationally-based alliance of interest around the energy fortune in the region and a containment tool against both Turkey and Russia. The U.S. is also aiming to benefit from the lucrative market of energy in the region, as it plans to increase its exports and have an upper hand over Russia, which will cause a strategic backlash in the form of reduced Russian gas exports to Europe in the long term. In terms of the main U.S. objective of containing Russia, taking a chunk of the European cake of energy demand will be a blow to the Russian economy. The U.S. is already making strides toward this objective by increasing its exports from Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) to Europe by 300 percent.21 According to the European Commission, in 2017 Europe accounted for more than 10 percent of total U.S. LNG exports, up from 5 percent in 2016. In 2018, around 11 percent of U.S. LNG exports went to the EU, while in the nine-month period from August 2018 to April 2019, in which exports surged by 272 percent, that share jumped to almost 30 percent.22 Since July 2019, the U.S. has almost tripled its natural gas exports to the EU and signed new licenses aiming to develop American energy as a pillar of EU energy security. Washington’s LNG campaign came when the EU was trying to establish a trade truce with President Trump and escape future U.S. car tariffs; it also aimed to crack Russia’s hold on energy markets in Europe.23

Rick Perry, former U.S. Secretary for Energy, signed two export orders for LNG in Brussels on May 2, 2019, in a move intended to double America’s export capacity to Europe to 112 billion cubic meters per year as of 2020. Perry said that the move would “free Europe” from the grip of Russia, just as seventy-five years ago in WWII, the U.S. freed the continent from the Nazis.24 The U.S. also signed a 24-year deal to deliver U.S. LNG to Poland as a signal to Europe of ensuring energy security and easing dependence on Russian supplies. “This is a signal across Europe that this is how your energy future can be developed, the security of the country, the diversity of supply –this is a great day for Europe,” Perry said at a signing ceremony in Warsaw with Polish President Andrzej Duda.25

These U.S. moves to contain Russia and disrupt the plans of its partner in the energy sector, Turkey, to be a regional hub, are aimed to enhance the U.S.’s stance in the region while helping Europe diversify its energy sources away from its Eastern flank; together they will make a significant change to the geopolitical map of the region in the long run.

Biden’s Possible Choices

From the viewpoint of American foreign policy, the dispute in the Eastern Mediterranean can be categorized as a Low-Intensity Conflict (LIC), defined as a “political-military confrontation between contending states or groups, below conventional war, and above the routine, peaceful competition among states.”26 Despite the military harassments between maritime military units stationed in the Mediterranean basin, the possibility of a full confrontation or the eruption of an all-out war between the different actors is very unlikely for a number of reasons, the most important of which is that such a confrontation could turn into a World War III, given the number of stakeholders and the variety of regional and international actors involved.

Maintaining the U.S. power projection in this region is vital within Washington’s grand strategy of containing Russia’s resurrection and its renewed interest in the whole Middle East

Some observers have expressed optimism that the newfound hydrocarbon wealth of the Eastern Mediterranean could work as a catalyst for peace and integration rather than an impetus for military escalation. Giving the rationality of the regimes involved in the present competition and their win/lose calculations; the different parties can reach, in the end, a compromise that can address the fears of different stakeholders, with the help of diplomacy or international arbitration. But if Biden aims to fulfill some of the anti-Turkey plans, as it was surfaced in a video from December 2019, by means of more intervention in internal Turkish politics with the aim of a regime change,27 this will be a game-changer in the regional conflict and hence the map of alliances.

The implications of a reckless U.S. policy in Biden’s era may force Turkey in the short run to make closer ties with Russia, which has offered to export its advanced Su-57 fighter to Turkey as an alternative to the American F-35 which has been blocked from Ankara. Having the Russian S-400 advanced missile system plus the Su-57 would further alienate Turkey from the West and would encourage it to upgrade more independent foreign and defense policies, especially toward the demarcation of its maritime border, and may lead to a militarization of the dispute in the region, which will have serious repercussions for the whole region in the near future.

So far, Turkey has opposed Russia’s strategies in Syria, Libya, and Azerbaijan, despite its dispute with America over its S-400 missile systems. An unjust intervention of the U.S. with Greece against Turkey would further complicate the situation, and could even pressure Turkey to consider buying the Russian multirole fifth-generation jet fighter Su-57, which could mark the de-facto end of its Western alliance. On the other hand, in order to reduce the security burden on the U.S., President Biden will have to rely on strong allies to monitor U.S. adversaries and safeguard mutual interests in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean, and Turkey is one of the most obvious partners to fill this role.28

Joining the EU in imposing sanctions against Turkey and its drilling activities in the region may still preserve the balance of power and status quo in favor of the Western allies; i.e. keeping the gas flowing despite the disagreement of Turkey by nourishing the new alliance between Israel, Greece and Cyprus could hurt the core of Washington’s strategy in the region: the containment of Russia. Without Turkey, this task will be much more difficult for the Western alliance, especially if Ankara were to join Moscow in its pursuit to expand its influence in the region and restructure the Turkish army’s defense posture.

Conclusion

The Eastern Mediterranean is regarded as a strategic region for the U.S., which has started to dedicate more efforts and assets in order to preserve its interests there, all the more so as it regards Europe as a lucrative market for fledgling U.S. energy exports. Maintaining the U.S. power projection in this region is vital within Washington’s grand strategy of containing Russia’s resurrection and its renewed interest in the whole Middle East. At the same time, it is an opportunity for the U.S. to reshape the map of alliances according to the current geopolitical transformations that enabled Russia and Turkey to expand their influence on the ground in the Syrian and Libyan conflicts, among other areas of the region like Qatar and Somalia29. This region is also vital to U.S. efforts to contain Iran, which is trying to expand its geostrategic reach to the Syrian shores. For this purpose too, the U.S. is keen to preserve and enhance its defense capabilities around the Mediterranean, as the region harbors approximately 80,000 military personnel in 28 main operating bases in Europe, in addition to the U.S. installations and hardware.

The Biden Administration’s choice either to deter Turkey or continue its integration into the Western alliance will shape the Eastern Mediterranean region for decades to come

Although the U.S. is reiterating its call for the demilitarization of the disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean, it is maintaining a high military profile around the region; it is transferring advanced weaponry systems to its allies across Europe, replacing old F-16 fighters with new stealth F-35s, which it denies to Turkey as a tool for punishing Ankara, along with other economical tools, as a gesture to keep it at bay and in the Western alliance and prevent it from a rapprochement with its arch-enemy Russia. While the U.S. strategists stress the importance of keeping Turkey in NATO, as it has the second-largest army in the alliance, they are also working on containing its rise and dealing with its assertive and independent foreign policy in the region, using all means available to prevent it from allying with Russia.

After becoming a giant energy supplier, the U.S. is using its newfound energy wealth to further contain Russia, both by offering Europe an alternative to Russian gas, and by having a say in the suggested pipeline projects and gas liquefying facilities through its presence as an observer in the East Med Gas Forum. The U.S. appears to be encouraging alliances against Turkey in the region, as it is also fortifying its alliance with Ankara’s regional rival Greece with enhanced defense agreements that aim to bypass Turkey in containing Russia in the region. The Biden Administration’s choice either to deter Turkey or continue its integration into the Western alliance will shape the Eastern Mediterranean region for decades to come.

Endnotes

1. Pinar Dost and Grady Wilson, “How Joe Biden Can Put US-Turkey Relations Back on Track,” Atlantic Council, (December 3, 2020), retrieved from https://bit.ly/3a40sJn.

2. Joseph R. Biden, “Why America Must Lead Again,” Foreign Affairs, (March/April 2020), retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://cutt.ly/0jxctM9.

3. Joseph R. Biden, “The Power of America’s Example: The Biden Plan for Leading The Democratic World to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century,” Joe Biden Official Website, retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://joebiden.com/americanleadership/.

4. “The U.S. Leads Global Petroleum and Natural Gas Production with Record Growth in 2018,” S. Energy Information, (August 20, 2019), retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=40973.

5. George Friedman, “The Origins of New US-

Turkish Relations,” Geopolitical Future, (October 14, 2019), retrieved from https://geopoliticalfutures.com/the-origins-of-new-us-turkish-relations/.

6. “US Sec of State Mike Pompeo: We Have Told the Turks that Illegal Drilling is Unacceptable,” National Herald, (October 6, 2019), retrieved from https://bit.ly/2PmwoOO.

7. “Energy Resources in Eastern Mediterranean: An Overview,” Anadolu Agency, (June 15, 2019), retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/energy-resources-in-eastern-mediterranean-an-overview/1504786.

8. “U.S. Becomes World’s Largest Crude Oil Producer and Department of Energy Authorizes Short Term Natural Gas Exports,” S. Department of Energy, (September 13, 2018), retrieved from https://www.energy.gov/articles/us-becomes-world-s-largest-crude-oil-producer-anddepartment-energy-authorizes-short-term.

9. Mark P. Fitzgerald, “The Eastern Mediterranean Needs More U.S. Warships,” Defense One, (June 4, 2019), retrieved from https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2019/06/eastern-mediterranean-needs-more-us-warships/157440/.

10. “U.S. Signs Extended Defense Agreement with Greece,” Greek City Times, (October 7, 2019), retrieved from https://greekcitytimes.com/2019/10/07/signs-extended-defense-agreement-greece/.

11. John Alternam et al., “Restoring the Eastern Mediterranean as a U.S. Strategic Anchor,” CSIS, (May 2018), p. 51.

12. “U.S. Sec of State Mike Pompeo: We Have Told the Turks that Illegal Drilling Is Unacceptable.”

13. “Turkey Iterates Vow to Defend Turkish Cypriots’ Rights,” Anadolu Agency, (July 10, 2019), retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/turkey-iterates-vow-to-defend-turkish-cypriots-rights/1528188.

14. “Turkey to Open New Page of Dialogue with EU, U.S. in 2021, Erdoğan Says,” Daily Sabah, (January 10, 2021), retrieved from https://cutt.ly/ijxbDOH.

15. “EU Leaders Approve Sanctions on Turkish Officials over Gas Drilling,” The Guardian, (December 14, 2020), retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/11/eu-leaders-sanctions-turkey-gas-drilling.

16. Lara Jakes, “U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Turkey Over 2017 Purchase of Russian Missile Defenses,” The New York Times, (January 10, 2021), retrieved from https://cutt.ly/bjxnkLO.

17. “How Long Can Turkey Show Its Military Might Abroad?” Deutsche Welle, (January 10, 2021), retrieved from https://cutt.ly/tjxmiq8.

18. “Energy Rresources in Eastern Mediterranean: An Overview,” Anadolu Agency, (June 15, 2019), retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/energy-resources-in-eastern-mediterranean-an-overview/1504786

19. Antonia Dimou, “Energy as an East Mediterranean Opportunity and Challenge,” National Security And The Future, Vol. 18, No. 1-2 (2017), pp. 82-83.

20. Dimou, “Energy as an East Mediterranean Opportunity and Challenge,” p. 89.

21. “U.S. Natural Gas Exports to Europe Soar Nearly

300% in Nine Months,” Oil Price, (May 2, 2019), retrieved from https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/US-Natural-Gas-Exports-To-Europe-Soar-Nearly-300-In-Nine-Months.html.

22. “U.S. Natural Gas Exports To Europe Soar Nearly 300% in Nine Months.”

23. “U.S. Boosts Natural-Gas Exports to EU, Aiming to Dent Russian Sales,” The Wall Street Journal, (May 2, 2019), retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-boosts-natural-gas-exports-to-eu-aiming-to-dent-russian-sales-11556827197.

24. “Freedom Gas: U.S. Opens LNG Floodgates to Europe,” Euro Active, (May 2, 2019), retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/freedom-gas-us-opens-lng-floodgates-to-europe/.

25. “US-Poland LNG Deal Will Ease Europe’s Reliance on Russia: Perry,” Euro Active, (November 9, 2018), retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/us-poland-lng-deal-will-ease-europes-reliance-on-russia-perry/.

26. Robert M. Gates, “Low Intensity Conflict: The Role of Intelligence,” CIA, (December 14, 1988),

retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP9901448R000301410001-

pdf, p. 3.

27. Vakkas Dogantekin, “US: Biden Hints at Interference in 2023 Turkish Polls,” Anadolu Agency, (August 16, 2020), retrieved from https://bit.ly/

28. Dost and Wilson, “How Joe Biden Can Put US-Turkey Relations Back on Track.”

29. Eric S. Edelman, “American Interests in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, (December 15, 2020), retrieved from https://bit.ly/2Nzu6Nx.