Introduction

The nearly 70 million refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and asylum seekers around the world are among the most vulnerable populations to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Of these, around 10 million live in refugee camps and informal settlements, which have especially high population densities.1 Refugees who live outside camps are equally vulnerable. It is not unreasonable to assume that a deadly virus, such as COVID-19, can spread swiftly among refugees and cause many casualties. Most refugee camps are still relatively safe from COVID-19, but they are ill-prepared to cope with it.2

There is a need to change the focus from the political and economic agendas of populist politicians −who tend to weaponize the virus for political reasons− to a human-crisis-generated approach to focus on how the spread of a global pandemic threatens all of humanity. As one expert reminds us, safeguarding vulnerable and marginalized groups will not only help manage the COVID-19 crisis effectively by curtailing the degree of global spread but it may also smooth the path for improving the health and well-being of refugees over the longer term.3 The politicization of the refugee phenomena, in other contexts related to war-stricken environments, has taught us not to lose sight of the humanitarian management of such crises.4

This essay seeks to demonstrate that there are both ethical and practical considerations for enabling refugees to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that a majority of refugees live in highly congested contexts, particularly urban areas, an outbreak would swiftly spread through their local communities. Evidence suggests that the lack of capacity to manage the spread of COVID-19 among refugee populations is bound to place many parts of the world at peril. Provoking xenophobic fears of mass movement of refugees across borders does little to stem the spread of the coronavirus in those refugee camps and particularly urban areas currently in danger of becoming infected. This is not to suggest, however, that open borders should be unconditionally embraced, but rather to outline practical and ethical frameworks that render possible, effective responses to the pandemic disease.

Our argument is twofold: (i) That a new approach is needed to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic −one that recognizes mounting challenges facing refugees and relies on international cooperation rather than the myopic rhetoric and sentiments of xenophobic right-wing politicians; (ii) That helping refugees to combat the spread of this deadly pathogen cannot be divorced from social contexts, hence the necessity of improving employment, basic health services, and educational opportunities for the refugees.

In the sections that follow, we first explore the challenges that refugees face. We next turn to the case study of Turkey, a nation that has hosted over 3.5 million Syrian refugees who are predominantly settled in urban areas, to demonstrate its handicaps and successes. It is within this context that we examine the EU-Turkey deal with an eye toward understanding its potential consequences for managing the refugee crisis facing Europe. In the ensuing section, the essay examines the hidden vulnerabilities to which refugees are exposed. Of particular relevance to this essay is the gravity of the situation that women refugees face in the wake of this deadly virus. Finally, we examine the ways in which refugees’ rights can be best protected amid the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the Gaza Strip, the highly infectious coronavirus could wreak havoc in one of the most densely populated and impoverished countries of the world

Avoiding an Unspeakable Tragedy

The healthcare status of refugees will remain a subject of renewed debate for many years to come. Reports suggest that approximately 5 million Venezuelans have fled economic chaos, crossing the border into neighboring Colombia and other countries. Many of them now reside in crowded apartments in Bogota, where the bulk of Colombia’s COVID-19 cases have emerged, and work as street vendors. During the country’s national lockdown, many have been evicted from their apartments and fined for illegally working on the streets as they struggle to survive. These refugees have increasingly become, according to Marianne Manjivar, International Rescue Committee director for Colombia and Venezuela, “invisible, locked away behind closed doors.”5

In two sprawling camps in Kenya, Somalis have survived several decades of drought, starvation, and war, fearing more uncertainty to come. Similarly, in Syria’s war-torn Idlib province, only one small health facility is equipped to receive suspected coronavirus cases. The World Health Organization (WHO) has sent 5,900 testing kits to Idlib, where they have been rigorously allocated. As of mid-April 2020, WHO authorities have completed nearly 200 tests, with no positive cases detected.6

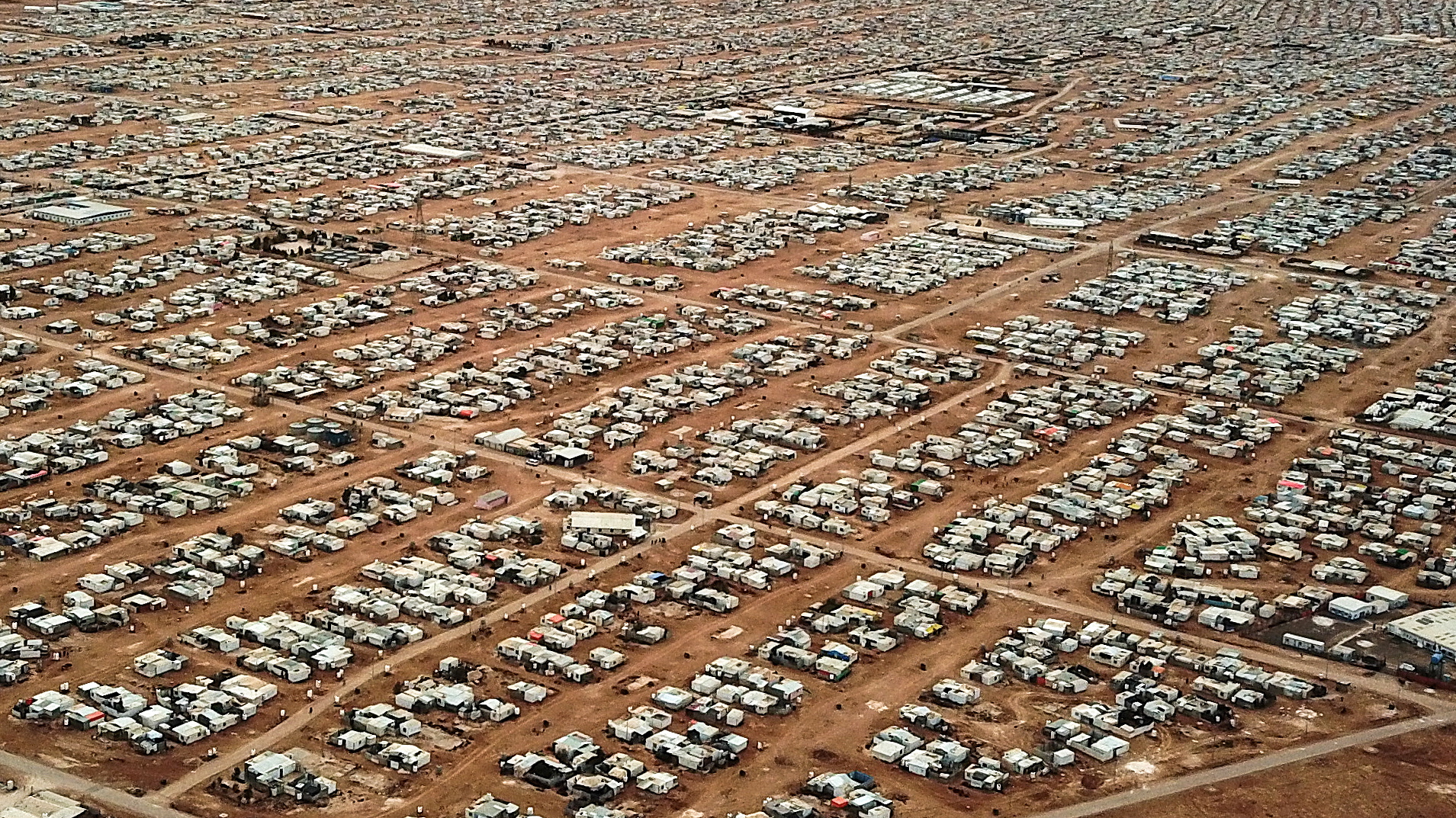

In Jordan, according to the UN refugee agency, the two largest camps for Syrian refugees have been sealed since March 2020. In Za’atari, host to 80,000 refugees, the Jordanian government conducted 150 random tests, all of which came back negative. Residents of Azraq, home to about 40,000 refugees, will be the next site of testing. All these camps suffer from fragile health care systems.7 Sealing camps reduces already limited opportunities for mobility, curtailing employment and self-dependence of the refugee populations, and rendering them powerless in protecting their own health. Some experts have warned that COVID-19 has yet to penetrate the refugee camps the way it has hit many parts of the world. Chris Boian, a senior communications officer with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), asserts that, on balance, there have been “relatively low numbers of suspected or confirmed cases among refugees.”8 This may be partially a function of the remote and desolate location of many of the world’s refugee camps. Taking into consideration that most of the world’s refugees reside in urban or peri-urban areas, Boian notes, that a vast majority of the refugees live in low- or middle-income countries with poor health conditions. It bears remembering, Boian posits, that the majority of the world’s refugees live in urban settings, not in camps. They are indeed “an integral part of the communities that they live in, which illustrates why it is so important to make sure that they have access to health facilities, services, and information.”9

Aerial view of Zaatari refugee camp, in Northern Jordan close to Syrian border, opened in 2012 and hosts 80,000 refugees. VALERY SHARIFULIN / TASS via Getty Images

Aerial view of Zaatari refugee camp, in Northern Jordan close to Syrian border, opened in 2012 and hosts 80,000 refugees. VALERY SHARIFULIN / TASS via Getty Images

Increasingly, however, confirmed COVID-19 cases have begun appearing in refugee camps. In Lebanon, the pandemic has posed a serious threat to refugees in the Palestinian camps, who already face many difficulties, including overcrowding, poverty, mass unemployment, and poor infrastructure. Unable to withstand the economic impact of this public health crisis, these camps face the possibility of closing as refugee labor income needed to run the camps is significantly diminishing.10 In the Gaza Strip, the highly infectious coronavirus could wreak havoc in one of the most densely populated and impoverished countries of the world. Given the shortage of testing materials, ventilators, drugs, and medical supplies, the risk of the exposure to COVID-19 will put enormous pressure on Gaza’s densely packed population, especially in the refugee camps, which are run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which was created in 1949 to provide for the relief and human development of Palestinian refugees.11

Preventive care clinics have been inoperative, including those that provide vaccinations, newborn screening, and children’s and maternal health care

In Israel, according to one study, the construction, agriculture, nursing, and health sectors have been ordered to remain open despite national lockdowns. With more than 100,000 Palestinians in the construction sector, which constitutes 13 percent of Palestinian GDP, Israel’s failure to protect these workers has left them exposed to serious health risks. As of May 15, 2020, this study finds that “Israel had 16,539 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 262 deaths. There have been 548 confirmed cases and 4 deaths in the Palestinian territories of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem.”12 The pandemic has heightened already existing patterns of debt, surveillance, labor exploitation, and Israeli’s clout over Palestinian territories and life.13

Nidal al-Azza, Director of Badi Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, notes that Palestinian refugees in the West Bank continue to face food shortage, a lack of personal protective equipment, and mounting economic pressure. Furthermore, Israel has refused to conduct any testing on political prisoners in Israeli jails and has provided no substantial protections to the Palestinian prisoners, nor has it responded positively to calls for releasing prisoners −some of whom are ill, elderly, and even children.14

Paradoxically, but understandably, such low rates of infection compared to the rest of the region appear to be a function of Gaza’s blockade and isolation. The irony is not lost on Salam Khashan, a physician who works at the Nasser Medical Complex in Khan Yunis in the Gaza Strip, pointing out that “For the first time in our lives, the blockade gives us an advantage.”15 Needless to say, the economic pressure that the blockade has exacerbated clearly renders it challenging for Khashan to convince her patients to stay at home: “If people do that, maybe they can escape the coronavirus, but they can’t escape the lack of supplies or the lack of food.”16

In Greece, Moria migrant camp was destroyed by fire following altercations when 23 asylum seekers tested positive for the coronavirus. Bangladesh imposed a lockdown on March 24, 2020, after the first case of the COVID-19 virus was reported in one of the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. Together these camps house more than 1 million Rohingya Muslims.17 One study in mid-April 2020 indicated that there were no known COVID-19 outbreaks in other major refugee camps. Yet many aid groups have predicted that it was only a matter of time before the disease strikes such camps. Host nations, they point out, have been sluggish to execute preventative measures. Many public health experts continue to fear that aid organizations are unlikely to effectively mobilize support and respond.18

Lockdowns and movement restrictions have postponed or diminished many of the proposed projects pertaining to education, mental health, maternal and reproductive health, and gender equality in refugee camps, diminishing humanitarian activities of governments, NGOs and volunteers to unprecedented low levels. Refugees in Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan rely on a hotline to a single psychiatrist and one nurse for all their mental health needs.19 Preventive care clinics have been inoperative, including those that provide vaccinations, newborn screening, and children’s and maternal health care. The pandemic and associated lockdowns have reintroduced stressors in the lives of refugees including fear of separation or loss of their loved ones, violence against women and children, and financial insecurity for people whose economic livelihoods are, at best, precarious.

The emphasis on health risks encountered in refugee camp sites mask the broader vulnerabilities that the novel coronavirus has created among millions of urban-dwelling refugee populations. Urban-dwelling refugees tend to be generally outside of the assistance framework of government ministries and international organizations. Instead, they are reliant on the local support organizations, their ethno-religious kin and informal networks to gain access to information and resources. With lockdowns and shelter-in-place regulations that have halted public transportation, urban refugees have lost most of their access to the local civil society organizations and networks that sustain them. Insecurities pertaining to registration and documentation problems create ambivalence among urban refugees toward local police, the healthcare system and government officials at a time when having access to government-led information and resources is pertinent to survival rates.

In addition, closure of low-paying positions such as domestic service and agriculture has rendered great financial insecurity among urban refugees who are typically employed in the informal markets. Severe restrictions on travel and limits on public transportation have decimated refugee women’s mobility, hindering their precarious employment prospects and access to resources. With the moratorium of the activities of the local civil society organizations in urban areas, and lack of school access for their children and associated loss of social programs such as conditional cash transfers, refugee women have lost their ability to support their families, as well as legal and social assistance to protect themselves from sexual and gender-based violence and predators who seek to take advantage of their vulnerabilities.

The living conditions of urban refugee populations make them particularly vulnerable to the contagion, where staying at home “sheltered” may not be safe due to crowded living situations, high risk of community transmission and domestic violence perpetuated by economic fragility and insecurity. Urban refugees in Uganda, where 82 percent of the refugees are women and children, suffer from unavailability of culturally and linguistically appropriate and accurate information on the pandemic as well as access to basic resources necessary for sanitation.20 Most of their access to communal sources of water has been disrupted due to mobility restrictions associated with the pandemic. Urban refugees’ linguistic difficulties may prevent them from being able to learn and follow governmental regulations. Furthermore, as outsiders to the local communities, urban refugees are typically stigmatized as possible transmitters of COVID-19, restricting compassion from health care professionals and access to life-saving medicines and quality care.

Programs like the Conditional Cash Transfers for Education give money to families that allow their children to go to school instead of making them work in the informal sector

The Turkish Case

Turkey has become a safe haven for refugees, asylum seekers, and irregular migrants from across the world. Since protests began in the 2011 Arab spring uprisings, millions of Syrians have fled their homes in hope of finding safety in the midst of the civil war in that country. In total, Syrian refugees, asylum seekers, and irregular migrants constitute 6 to 7 percent of the total population in Turkey.21 This is equivalent to over 5,000,000 people,22 in addition to the pre-existing Turkish nationals, in need of government support during the era of COVID-19.

After an abnormally long period free of the virus and with multiple neighboring countries already battling COVID-19, Turkey documented its first case on March 11, 2020. 23 In late April, Turkey was on the list of worst affected countries.24 By May, Turkey had 122,392 confirmed cases and 3,258 deaths from the coronavirus.25 Although the infections spread rapidly, Turkey was able to provide over a million coronavirus tests to its citizens and significantly limit the spread of the virus.26 Despite the prevalence of the virus among the population and the rapid increase of infection rates, what Turkey’s low death rate was striking. As of April 30, 2020, total deaths in Turkey (3,081) were far fewer than in Germany (6,467), UK (26,097), France (24,087), Italy (27,682), and Spain (24,275). On the basis of official figures, Turkey ranked better than Germany, which has been praised for its low fatality rates. Even with the rapid spread of the infection, what also was unique is that Turkey’s healthcare system was not overburdened, making Turkey even more successful than most comparable European countries for COVID-19.27

Due to ample preparation and precautionary measures, within a day of the first confirmed case, all schools were closed and able to continue online classes within a week.28

Before the coronavirus reached Turkey, all 81 provinces were prepped and prepared for the outbreak.29 Excessive stockpiles of medical supplies, new technological advances in COVID-19 testing, and pre-approved national plans for viral containment, helped make Turkey a leading actor in the fight against this pandemic. Turkey has exported coronavirus related supplies to 30 countries and has received medical equipment requests from 88 countries.30

As stores began to close and the economy faltered, workers faced decreasing job prospects. Concurrently, the Turkish government worked to financially support its citizens. In March 2020, Turkey started the Economic Stability Shield as a way to provide $14.93 billion for taxpayers.31 Citizens who were laid off from the formal sector, need unemployment relief, need to postpone loan payments, or need other types of financial flexibility and assistance; they can receive financial support through this fund.32

However, approximately one third of Turkish citizens, along with a large majority of Syrian refugees, asylum seekers, and irregular migrants, work in the informal sector and do not qualify for the program.33 People who work in the informal sector are exempt from paying income tax and hence are not registered as employed by the country. Unfortunately, a majority of jobs within this sector cannot be plausibly performed at home, and many people have been fired as a result.34 With no jobs or government aid available, millions of people living in Turkey are left without an income.35 Urban refugees bear the brunt of this burden since about 1.5 million Syrian refugees are employed in the informal sector, with legal work permits limited to only 35,000 refugees.36 Predominantly employed in textile and construction sectors that increase their exposure to volatility of economic recession as well as the novel coronavirus, urban refugees lack government-provided social security networks, sick leave or unemployment assistance, increasing the chances that the workers would continue to attend to their jobs even if they are sick.

Furthermore, urban refugees in Turkey have restricted access to free health care assistance limited to their province of registration. Many refugees are registered in small towns but prefer to live and work in larger cities such as İstanbul and İzmir due to availability of informal employment opportunities. Under-reporting of illnesses is very common due to fear of crack-down by government authorities on irregular workers or refugees outside of their province of registration.37 Irregular migrants lack access to the public health care system according to domestic regulations, further compounding the problems of access and equity in the country’s healthcare system. While the government has suspended some of these restrictions, urban refugees and irregular migrants are still reluctant to report to hospitals for fear of deportation.38

Although the Turkish government is attempting to stabilize the economy, a large number of people residing within its borders are overlooked. For example, protective masks are mailed though the national postal service to citizens that apply, but not to unregistered individuals.39 All people in Turkey must wear face masks in public places and markets,40 but many unregistered refugees lack the supplies and the money to adhere to the rules without help. While Turkey has instigated limited lockdowns over the weekends and holidays for the working populations, both seniors and children have had stricter shelter-in-place requirements. These regulations led to dense and uncomfortable living accommodations for extended periods of time, leading to higher rates of domestic violence. People older than 65 and younger than 20 have been strictly ordered to stay at their homes, and the rest of the population to stay in to the extent possible. Although there are no official figures, women’s rights activists in Turkey noted that there has been a noticeable increase in cases of domestic violence during the lockdown. “There are significantly more people calling our hotlines,” said Gülsüm Kav, the director of We Will Stop Femicide Platform. Moreover, “Due to the lockdown measures, she said, men are staying at home more often than usual and women and children who are subjected to domestic violence cannot escape.”41

TİKA, a Turkish state-run aid body, donates 5,000 personal care packages for the Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh on April 29, 2020.AA

TİKA, a Turkish state-run aid body, donates 5,000 personal care packages for the Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh on April 29, 2020.AA

To make matters worse, schools in Turkey were closed for several months.42 Education Minister Ziya Selçuk released televised and internet classes that were and are still available to the general public.43 However, many refugees in Turkey live in “crowded and often particularly squalid conditions.”44 Urban refugees in Turkey live in shantytowns or apartments at the outer edges of major cities and rely on public transportation to reach their place of employment during the weekdays, increasing their exposure to the virus. Many asylum seekers, refugees, irregular migrants, and Turkish residents living below the poverty line are struggling to buy food, let alone have access to devices that can stream online lectures. With such a sharp economic decline, unstable employment, and poor living conditions, many families will be unable to provide their children with educational opportunities for months to come.

Programs like the Conditional Cash Transfers for Education (CCTE) give money to families that allow their children to go to school instead of making them work in the informal sector.45 In these dire times many families may need financial support from their children and will no longer be able to participate in such programs. Many refugee students depend on the interventions of the local NGOs to access online schooling. The longer schools are online, with no supportive aid provided to families without the resources necessary to allow children to access the material, the greater the educational gap between the rich and the poor will become. This situation is alarming given the prime significance of education as a social equalizer.

In addition to declining educational opportunities due to technological insufficiencies, there is also a language barrier to consider. Refugee children living in new countries often develop fluency in the new language by interacting with peers in schools. Without those social interactions, language development is extremely difficult. The ability to learn languages decreases with age.46 The longer these children are prevented from establishing these skills, the more problematic their learning experiences become. In addition, children who cannot speak Turkish are unable to learn from the online classes even when they have access to the material, presenting further educational constraints.

Despite shortcomings with financial and educational programs implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, Turkey has exemplified a successful case. Turkey is a model for how preparation, excessive testing, fast responses, and unified decisions can help curb the spread of COVID-19

Despite shortcomings with financial and educational programs implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, Turkey has exemplified a successful case. Turkey is a model for how preparation, excessive testing, fast responses, and unified decisions can help curb the spread of COVID-19. Although there are deficiencies in support for Syrian refugees, asylum seekers, and irregular migrants, Turkey has successfully countered the coronavirus. Less than two months after the virus reached Turkey, Health Minister Fahrettin Koca confirmed that the number of recoveries doubled and that there were less than 2,000 new cases of COVID-19 daily. Over summer 2020, however, new cases erupted, especially in southeast provinces and the capital city Ankara.47 However, currently, COVID-19 infection rate is on the rise in İstanbul.48 These difficulties notwithstanding, Turkey continues its efforts to make gradual recovery possible. The Economist praised Turkey’s well-structured health system as the key reason behind bringing the coronavirus infection under control. Most notably, The Economist noted, President Erdoğan and his governments have poured tens of billions of dollars into health care by building a massive network of hospitals. As a result, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic failed to inundate the Turkish health system. This success was attributed not just to President Erdoğan and his impressive Health Minister, Fahrettin Koca, but also to opposition mayors, especially in big cities such as İstanbul and Ankara, who have done a great job of raising funds and organizing the distribution of masks.49

Latent Vulnerabilities

Infectious diseases tend to take a heavy toll on refugees, IDPs, and asylum seekers, but the 2019 coronavirus pandemic poses an unusually novel threat. According to Annick Antierens, a strategic adviser to the medical department for Doctors without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières, MSF), “Any kind of epidemic is never good, but particularly not this one, where physical distancing is impossible and home isolation is a joke.”50 Practicing physical distancing and isolation in the highly congested environments in which most refugees live is virtually impossible.

With millions of refugees trapped in camps −from Bangladesh, through Greece, to the U.S.-Mexico border− and many more in crowded squalid living conditions in urban locations, the situation worsens, given that most refugees have no access to tertiary care.51 Many refugees and IDPs are at greater risk due to the current policies, and practices of those in authority, of the host countries. Aurelie Ponthieu, Coordinator for Forced Migration at MSF, notes that, “There is a risk some countries could use COVID-19 to impose draconian measures toward refugees and asylum seekers.”52

The crisis has also brought a halt to search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean. Refugees hoping to find protection in Europe often cross the sea. However, European countries no longer accept boats carrying migrants, with the justification of slowing the spread of COVID-19. Those migrants who have already made it to the shores of countries, such as Greece, are kept in collective quarantines in asylum centers, often with less than optimal medical facilities.53 In the United States, refugee resettlement programs were temporarily suspended in March 2020. Stigmatization places urban-dwelling refugees at particular risk. Many populist politicians and citizens in Europe blame refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers for the outbreaks. The prevailing mood of fear and anxiety continues to play to populists’ political strengths as normal life comes to a halt.54

Europe’s far-right nationalists have closed their borders while using COVID-19 as an excuse to deport and deny entry to refugees and asylum seekers. The current pandemic has not only proliferated but has also infected societies with a growing sense of insecurity, fear, and demoralization. Consequently, it has become increasingly common to point a finger of guilt toward refugees and migrants.55 This politicization of the virus is likely to unleash a new wave of xenophobia and racial politics and to boost far-right groups in many European countries. This trend, along with the declaration of a global health emergency, will presumably allow governments to enforce temporary immigration and health-related policies that could systematically target refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in the name of viral containment.56 It is both morally and practically indispensable to treat refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers with compassion, dignity, and care.

Refugees hoping to find protection in Europe often cross the sea. However, European countries no longer accept boats carrying migrants, with the justification of slowing the spread of COVID-19

Taking a myopic perspective towards managing the current pandemic, falls short of providing the answers necessary to ending the massive humanitarian crisis, while also rendering the future wave of coronavirus more threatening.57 The risk of undue stigma on refugees and IDPs is high. If the refugee camps or refugee settlement areas in urban or peri-urban locations get hit hardest with the outbreak, they are likely to become easy targets for political leaders seeking to deflect blame from their administrations and themselves. Such claims will further stigmatize this population. This can create a vicious feedback loop where refugees and IDPs are further marginalized, causing the progressive deterioration in the conditions. This situation is certain to enhance higher susceptibility to outbreaks and give rise to contexts that can then be manipulated by political leaders seeking to further scapegoat these already challenged displaced persons.58

Refugee Women at Risk

Of the world’s 70 million people coercively displaced by civil wars, forced migration, climate change, natural disasters, and humanitarian crises, more than half of them (approximately 41 million) are women and girls.59 Many of these displaced individuals generally face a variety of constraints based on their displacement status, and often live in countries with weak health protection regimes. Approximately 9.5 million women, according to one study, could lose access to contraception and safe abortion due to the COVID-19 crisis −a possibility which will most likely lead to women and girls dying from utterly preventable diseases. Due to mobility restrictions, one health center in Nepal, for instance, has faced enormous surge in calls for women seeking abortion services. These women and girls are likely to pay heavy prices if the government cannot guarantee access to substantial healthcare, including safe abortion and contraception.60 How can these women be protected from such calamities and abuses? What can contribute to their decision-making autonomy and financial independence?

Suggestions to address these issues abound. Some experts have suggested the decentralization of decision-making functions by simply localizing support services and manpower, while providing work permits to refugees, allowing them to enjoy gainful, legal employment opportunities. However, access to such local programs has typically come to a halt due to the COVID-19 restrictions and shelter-in-place regulations. According to the EU-Jordan compact, the Jordanian government has provided work permits to a large number of Syrians.61 The inability to pursue income-generating activities and the isolation from family and traditional social networks of support, continue to present problems.62 Vulnerable groups −including women subject to gender-based violence, former child soldiers, unaccompanied and orphaned minors, and individuals with physical and mental disabilities− all face extraordinary levels of ongoing stress in the absence of local programs that would provide much needed support.63

Women refugees, according to the International Rescue Committee, also encounter significantly more legal barriers to employment than men

Other experts have expressed similar concerns. Among the wide array of psychosocial interventions aimed at relieving distress and promoting the well-being of refugees, they have consistently mentioned the lack of opportunities for employment and income generation.64 Women refugees, according to the International Rescue Committee (IRC), also encounter significantly more legal barriers to employment than men. These barriers include laws that prevent women from entering certain industries, a failure to implement equal pay for equal work, as well as a range of restrictions on women’s rights to work after marriage or childbirth.65 With domestic service and other low paying jobs at risk due to the COVID-19 restrictions, refugee women are facing a higher risk of urban destitution than ever before.

Women from low-income communities, especially from the Global South, bear a larger and intolerable burden from the adverse effects of climate change in part because of the historic and ongoing impacts of colonialism, racism, and inequality. In many cases, these women appear to be more dependent on natural resources for their survival and/or live in areas that have dilapidated infrastructure. Additionally, several other difficulties, including drought, flooding, and unforeseeable weather patterns, pose daunting challenges for many women, who are typically responsible for providing food, water, and energy for their families. The disproportionate impact of climate change on women and the resulting inequities demand the urgency of dealing with the global climate justice.66

The UNHCR has warned that refugee and migrant women are likely to be forced into “survival sex” or child marriages. “We need to pay urgent attention to the protection of refugee, displaced and stateless women and girls at the time of this pandemic,” noted Gillian Triggs, the UNHCR Assistant High Commissioner for Protection. To counter this burgeoning risk, the UNHCR has distributed emergency cash to survivors and women considered to be at risk of gender-based violence.67 While the international community fights the contagion on multiple fronts, it is worth bearing in mind that “repercussions of their mitigation and suppression measures, as they might deepen inequalities between the developing and developed world, poor and rich within societies, women and men, and vulnerable populations.”68

The Global Refugee System

Well before the eruption of the current pandemic, experts noted the flaws of the international refugee system. They attribute the regression of the global refugee system partially with EU policies being shaped more by current domestic politics than by the search for collective solutions. Both international agencies and the UN lacked a clear strategy for the international refugee system.69 The spread of the COVID-19 virus has not only exposed the shortcomings of the broken refugee system, in place since 1951, but also presented new opportunities for refugees.

The participation of refugees in locally led organizations merits particular attention in the wake of the current global pandemic. There is a possibility to build new collaborations, enduring models of participation, and inclusive humanitarian governance. UN agencies have attempted to raise funds to support international NGOs to distribute essential items, while also bolstering health facilities in camps around the world. The capacity of the international humanitarian system, however, cannot meet these needs. The UNHCR has halted its regular missions into camps and suspended global resettlement of refugees for the duration of this pandemic.70

In Uganda, home to approximately 1.4 million refugees, national lockdowns have created a unique opportunity for refugee-led organizations to contribute support in both camps and cities. In the Nakivale Settlement, in Uganda, the Wakati Foundation has sewn and distributed masks to the community. The foundation has adapted itself to the new conditions by employing refugees to produce face masks and raise awareness about the COVID-19 throughout the community.71

Similarly, in Nairobi, Youth United for Social Mobilization (YUSOM), a non-profit youth organization, has partnered with other community organizations to dispatch a coronavirus public information campaign. Refugee-led organizations are capable of performing wide-ranging roles in the current crisis, “including distributing supplies, disseminating public information, serving as community health workers, tracking and monitoring, and influencing social norms.”72 While many of these organizations lack the necessary capacity, they often enjoy advantages in building community-level trust, social networks, and adaptability −elements that are essential during pandemics. Although they may not serve as a surrogate for traditional humanitarian assistance, they can supplement the broader mission.73

Governments in Africa can do more by strengthening health facilities, providing basic anti-coronavirus support, increasing testing, promoting more community engagement, preventing the spread of xenophobia, and building stronger public-private partnerships

These examples should not detract attention from what governments can do to make basic health services available to refugees and to lessen the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, one observer notes that Algeria has built reception and accommodation centers for refugees to access routine medical checkups, as well as broader national health services. In low-to-middle income countries such as Bangladesh, population density and the presence of large numbers of stateless Rohingya, who have been driven out of Myanmar by a well-founded fear of persecution and ethnic cleansing, make it impractical to shelter-in-place in urban slums. The government agencies there are seeking solutions in the form of mobile healthcare facilities and sanitation centers.74 In Ethiopia, all refugees have the right to basic health services while also being treated like their host communities. In Uganda, refugees have been granted integrated comprehensive healthcare packages.75 Governments in Africa can do more by strengthening health facilities, providing basic anti-coronavirus support, increasing testing, promoting more community engagement, preventing the spread of xenophobia, and building stronger public-private partnerships.76

It is also worth noting that Turkey has played a critical role in the current regional refugee crisis, while retaining resettlement to a third country

The Way Forward

The examination of structural barriers to accessing health services for refugees, forced migrants, and asylum seekers remains a neglected and underdeveloped area of study at best, and a devastatingly worrisome one at worst, even though it provides valuable insights into several dimensions of the lived experience of forcibly displaced populations. The provision of access to health services −especially with regard to mental health needs− represents a robust indicator of state commitment to asylum seekers and refugees within countries of interim refuge or resettlement.77

As noted in the preceding sections, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated refugees’ lives, both in camps and urban areas in war-affected nations. Migrants and refugees in urban areas are often stigmatized and unjustly discriminated against for spreading disease and such unacceptable attitudes further risk wider public health outcomes, including for host populations, since refugees and migrants could be fearful to seek treatment or disclose symptoms.78

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has given populist-nationalist politicians yet another excuse to scapegoat refugees and impose additional constraints on them. For the moment, writes Abrahm Lustgarten, with the coronavirus pandemic effectively sealing borders, refugees have been trapped in protracted transit, unable to move around in their journey. Similarly, migrants, caught in this process, stray the streets, unable to keep social distancing while also lacking even basic sanitation.79 Choking off legal crossings lay bare the moral deficiency of anti-immigration political posturing in the name of national interest. In these uncertain times and this unnatural state of affairs, what binds us together is a strong commitment to empathy and solidarity with the world’s refugees and displaced persons.

Turkey’s success in imposing stricter measures, including nationwide lockdowns, as well as its low death rates, was emblematic of its timely and useful measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also worth noting that Turkey has played a critical role in the current regional refugee crisis, while retaining resettlement to a third country. Over the past four years, several important policy developments have shaped Ankara’s refugee policies. First, the Turkish government has taken a number of steps to bring its refugee policies more closely in sync with international standards −even though some differences still remain− and adopted new measures to provide Syrian refugees with educational opportunities and considerable number of work permits. Ankara also has become more receptive to accepting international aid, while also reducing constraints on the operations of international humanitarian organizations and other NGOs −a palpable shift from its original stance of relying on its own resources to meet the massive refugee needs, even though cooperation with the international community has remained somewhat challenging to say the least.80

If coronavirus has taught us anything about our shared vulnerability as human beings, it is that our health and safety are inextricably intertwined with others’ physical, mental, and emotional well-being. The need for collective action and collective consciousness has never been more important and obvious.81 This is not to argue for open borders, but rather to underscore the importance of protecting the legal and moral rights of refugees to seek sanctuary in places other than their countries of origin.82 Closed borders and travel bans provide no long-term solutions and full lockdowns of refugee camps as implemented in Jordan and Lebanon only serve to exacerbate inequality and marginalization and further victimization of vulnerable populations.83 Instead, ensuring that refugees, migrant workers, and asylum seekers are incorporated into public health programs around the world would offer sustainable results.84

Safeguarding refugees and the forcibly displaced from the current crisis will serve to restrain the global spread of COVID-19 in addition to fulfilling international human rights laws and the refugee protection regimes

To prevent this fiasco from deepening requires imagination, common sense, and a high degree of realism. Safeguarding refugees and the forcibly displaced from the current crisis will serve to restrain the global spread of COVID-19 in addition to fulfilling international human rights laws and the refugee protection regimes. Ultimately, the optimal result is judged not in terms of nationalism, but in the extent to which controlling an outbreak in one part of the world mitigates the risk in other parts of the world. To think in nationalistic terms, under the pretext of living in the age of uncertainty at a time when we all desperately seek to contain a common formidable foe, will result in an ethical catastrophe for displaced populations around the world.

Endnotes

1. “Lack of Virus Testing Stokes Fears in World’s Refugee Camps,” The New York Times, (April 22, 2020), retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2020/04/22/us/ap-virus-outbreak-refugees-at-risk.html.

2. “The World’s Refugee Camps Are a Coronavirus Disaster in Waiting,” The Economist, (April 6, 2020), retrieved April 26, 2020, from https://www.economist.com/international/2020/04/06/the-worlds-refugee-camps-are-a-coronavirus-disaster-in-waiting.

3. Muhammad H. Zaman, “Opinion: Refugees Are Especially Vulnerable to COVID-19. Don’t Ignore Their Needs,” NPR, (March 11, 2020), retrieved April 26, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/11/814473308/opinion-refugees-are-especially-vulnerable-to-covid-19-dont-ignore-their-needs.

4. For an illuminating discussion on this subject, see, Ruchira Ganguly Scrase, “Afghan Experiences of Displacement,” in Cecilia Menjívar, Marie Ruiz, and Immanuel Ness (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 407-425; see especially p. 421.

5. “Lack of Virus Testing Stokes Fears in World’s Refugee Camps.”

6. “Lack of Virus Testing Stokes Fears in World’s Refugee Camps.”

7. “Lack of Virus Testing Stokes Fears in World’s Refugee Camps.”

8. Elliot David, “Coronavirus Cases Rise in Refugee Camps,” US News.Com, (April 9, 2020), retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2020-04-09/coronavirus-cases-rise-in-refugee-camps-globally.

9. David, “Coronavirus Cases Rise in Refugee Camps.”

10. “Global COVID-19 Pandemic: Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon Need Support,” The al-Awad, (May 2, 2020), retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://al-awda.org/donations/support-palestinian-refugees/.

11. Joseph Hincks, “Israel’s Blockade Has Kept the Worst of the Coronavirus Out of Gaza: It Might Keep Aid Out Too,” Time, (April 3, 2020), retrieved May 4, 2020, from https://time.com/5814944/gaza-covid19-israel-palestinians/.

12. Lucy Garbett, “Palestinian Workers in Israel Caught Between Indispensable and Disposable,” Middle East Report Online, (May 15, 2020), retrieved May 15, 2020, from https://merip.org/2020/05/palestinian-workers-in-israel-caught-between-indispensable-and-disposable/.

13. “Palestinian Workers in Israel Caught Between Indispensable and Disposable.”

14. Amahl Bishara and Nidal al-Azza, “Voices from the Middle East: Palestinian Refugees in the West Bank Confront the COVID-19 Crisis,” Middle East Report Online, (May 14, 2020), retrieved May 15, 2020, from https://merip.org/2020/05/voices-from-the-middle-east-palestinian-refugees-in-the-west-bank-confront-the-covid-19-crisis/.

15. Hincks, “Israel’s Blockade Has Kept the Worst of the Coronavirus Out of Gaza.

16. Hincks, “Israel’s Blockade Has Kept the Worst of the Coronavirus Out of Gaza.”

17. David, “Coronavirus Cases Rise in Refugee Camps.”

18. Nidhi Subbaraman, “Distancing Is Impossible: Refugee Camps Race to Avert Coronavirus Catastrophe,” Nature, (April 24, 2020), retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01219-6.

19. Ziad el-Khatib, Mohannad al Nsour, Khader S.Yousef, and Mohammad Abu Khudair,“Mental Health Support in Jordan for the General Population and for the Refugees in the Za’atari Camp During the Period of COVID-19 Lockdown,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, Vol. 12, No. 5 (2020), pp. 511-514, retrieved August 3, 2020, from https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2020-47568-004.pdf.

20. Paul Bukuluki, Hadijah Mwenyango, Simon Peter Katongole, Dina Sidhva, and George Palattiyil, “The Socio-economic and Psychosocial Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Urban Refugees in Uganda,” Social Sciences and Humanities Open, (2020), retrieved August 3, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590291120300346.

21. Kemal Kirişçi and Murat M. Erdoğan, “Order from Chaos, Turkey and COVID-19: Don’t Forget Refugees,” The Brookings Institution, (April 20, 2020), retrieved May 1, 2020, from www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/04/20/turkey-and-covid-19-dont-forget-refugees/.

22. Kirişçi and Erdoğan, “Order from Chaos, Turkey and COVID-19.”

23. Tuvan Gümrükçü, “Turkey Confirms First Coronavirus Case, Wins WHO Praise for Vigilance,” Physicians Weekly, (March 11, 2020), retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.physiciansweekly.com/turkey-confirms-first-coronavirus.

24. Carlotta Gall, “Turkey Orders All Citizens to Wear Masks as Infections Rise,” The New York Times, (April 7, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/world/europe/turkey-virus-erdogan-masks.html.

25. “COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE),” John Hopkins University, (May 1, 2020), retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

26. “Turkey Completes Over 1 Million COVID-19 Tests; Number of Patients in Critical Care Declines,” Daily Sabah, (April 30, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/turkey-completes-over-1-million-covid-19-tests-number-of-patients-in-critical-care-declines/news.

27. Evren Balta and Soli Özel, “The Battle over the Numbers: Turkey’s Low Case Fatality Rate,” Institut Montaigne, (May 4, 2020), retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/battle-over-numbers-turkeys-low-case-fatality-rate.

28. Tuvan Gümrükçü, “Turkey’s First Coronavirus Case Shuts Schools, Impact Sports,” Reuters, (March 12, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-turkey/turkeys-first-coronavirus-case-shuts-schools-impacts-sports-idUSKBN20Z2RH.

29. Gümrükçü, “Turkey’s First Coronavirus Case Shuts Schools, Impact Sports.”

30. Sasha Toperich, “Turkey Emerges as Key Player in Global COVID-19 Fight,” The Hill, (April 12, 2020), retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://thehill.com/opinion/international/492628-turkey-emerges-as-key-player-in-global-covid-19-fight.

31. “Stimulus Package Shields Public From Pandemic as Turkey Charts Own Path to Protect Economy,” Daily Sabah, (April 12, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/stimulus-package-shields-public-from-pandemic-as-turkey-charts-own-path-to-protect-economy.

32. “Stimulus Package Shields Public from Pandemic As Turkey Charts Own Path to Protect Economy.”

33. Kirişçi and Erdoğan, “Order from Chaos, Turkey and COVID-19.”

34. Kirişçi and Erdoğan, “Order from Chaos, Turkey and COVID-19.”

35. Mahmut Bozarslan, “Turkey’s Syrian Refugees Among Hardest Hit Amid Coronavirus Pandemic,” Al-Monitor, (April 27, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/04/turkey-syria-refugees-most-affected-by-coronavirus-jobless.html.

36. Zeynep Balcioğlu and Murat M. Erdoğan, “What Does It Mean to Be an Urban Refugee in Turkey During a Pandemic?,” Open Democracy, (May 1, 2020), retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/what-does-it-mean-be-urban-refugee-turkey-during-pandemic/.

37. Balcioğlu and Erdoğan, “What Does It Mean to Be an Urban Refugee in Turkey During a Pandemic?.”

38. Balcioğlu and Erdoğan, “What Does It Mean to Be an Urban Refugee in Turkey During a Pandemic?.”

39. Gokhan Ergöçün, “Turkey Distributes Free Face Masks to Citizens,” Anadolu Agency, (April 5, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/turkey/turkey-distributes-free-face-masks-to-citizens/1793420.

40. Ergöçün “Turkey Distributes Free Face Masks to Citizens.”

41. Pelin Ünker and Daniel Bellut, “Domestic Violence Rises in Turkey During COVID-19 Pandemic,” DW, (October 4, 2020), retrieved November 10, 2020 from https://www.dw.com/en/domestic-violence-rises-in-turkey-during-covid-19-pandemic/a-53082333.

42. “School Closures in Turkey Extended Until May 31 Amid COVID-19 Pandemic,” Daily Sabah, (April 29, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/school-closures-in-turkey-extended-until-may-31-amid-covid-19-pandemic/news.

43. “Remote Courses Keep Education Open in Turkey While Schools Shut,” Daily Sabah, (March 22, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/education/remote-courses-keep-education-open-in-turkey-while-schools-shut.

44. Kirişçi and Erdoğan, “Order from Chaos, Turkey and COVID-19.”

45. Kirişçi and Erdoğan, “Order from Chaos, Turkey and COVID-19.”

46. Monika Schmid, “The Best Age to Learn a Second Language,” Independent, (February 8, 2016), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/the-best-age-to-learn-a-second-language-a6860886.html.

47. “Turkey’s Daily COVID-19 Cases Drop to Below 2,000, with Recoveries More Than Doubling,” Daily Sabah, (May 2, 2020), retrieved May 3, 2020, https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/turkeys-daily-covid19-cases-drop-to-below-2000-with-recoveries-more-than-doubling/news.

48. “COVID-19 Cases on Rise amid Nationwide Inspections,” Xinhuanet, (October 17, 2020), retrieved November 10, 2020 from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-10/17/c_139447623.htm.

49. “What Turkey Got Right about the Pandemic,” (June 4, 2020), The Economist, retrieved October

8, 2020, from https://www.economist.com/europe/2020/06/04/what-turkey-got-right-about-the-pandemic.

50. “Turkey’s Daily COVID-19 Cases Drop to Below 2,000, With Recoveries More Than Doubling.”

51. Neve Gordon and Catherine Rottenberg, “The Coronavirus Conundrum and Human Rights,” Al Jazeera, (March 21, 2020), retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/3/21/the-coronavirus-conundrum-and-human-rights/.

52. Lina Khatib, “COVID-19 Impact on Refugees Is Also Political,” Chatham House, (March 31, 2020), retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/covid-19-impact-refugees-also-political?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI1ICvyYKJ6QIVka_sCh1j_wDtEAAYAiAAEgK8XvD_BwE.

53. “COVID-19 Impact on Refugees Is Also Political.”

54. Jeremy Cliffe, “How Populist Leaders Exploit Pandemics,” Newstatesman, (March 18, 2020), retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.newstatesman.com/world/2020/03/how-populist-leaders-exploit-pandemics.

55. Haris Zargar, “Far Right Uses Coronavirus to Scapegoat Refugees,” New Frame, (March 19, 2020), retrieved April 28, 2020, from https://www.newframe.com/far-right-uses-coronavirus-to-scapegoat-refugees/.

56. “Far Right Uses Coronavirus to Scapegoat Refugees.”

57. “Far Right Uses Coronavirus to Scapegoat Refugees.”

58. Fouad Pervez, “Amid Global Coronavirus Outbreak, What About Refugees?,” The United States Institute of Peace, (March 18, 2020), retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/03/amid-global-coronavirus-outbreak-what-about-refugees.

59. Stephanie Johanssen, Mina Jaf, and Evelien Wauters, “We Cannot Abandon Migrant and Refugee Women During the COVID-19 Crisis,” Magazine, (April 15, 2020), retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://msmagazine.com/2020/04/15/we-cannot-abandon-migrant-and-refugee-women-during-the-covid-19-crisis/.

60. See, “9.5 Million Women Could Lose Access to Our Services,” Marie Stopes International, (April 3, 2020), retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://www.mariestopes.org/news/2020/4/95-million-women-could-lose-access-to-our-services/?page=0.

61. Dina Dajani, “Refugee Policy and the Post-Corona Ecosystem,” Center for Global Policy, (April 29, 2020), retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://cgpolicy.org/articles/refugee-policy-and-the-post-corona-ecosystem/.

62. Derrick Silove, Peter Ventevogel, and Susan Rees, “The Contemporary Refugee Crisis: An Overview of Mental Health Challenges,” World Psychiatry, Vol. 16, (June 2017), pp. 1301-1339; see especially pp. 133-134.

63. Silove, Ventevogel, and Rees, “The Contemporary Refugee Crisis,” p. 134.

64. Silove, Ventevogel, and Rees, “The Contemporary Refugee Crisis,” p. 135.

65. “For Women Refugees, Finding Work Is Doubly Hard,” Al Jazeera, (December 18, 2019), retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/women-refugees-finding-work-doubly-hard-

html.

66. “Why Women,” We Can: Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network--International, retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://www.wecaninternational.org/why-women.

67. “Refugee Women Face Greater Violence Risk During Crisis: UNHCR,” Al Jazeera, (April 20, 2020), retrieved May 3, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/refugee-women-face-greater-violence-risk-crisis-unhcr-200420064550330.html.

68. Elisa M. Maffioli, “Consider Inequality: Another Consequence of the Coronavirus Epidemic,” Journal of Global Health, 10, No. 1 (2020).

69. See especially, Betts and Collier,

70. Alexander Betts, Evan Easton-Calabria, and Kate Pincock, “Why Refugees Are an Asset in the Fight Against Coronavirus,” The Conversation, (April 28, 2020), retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/why-refugees-are-an-asset-in-the-fight-against-coronavirus-136099.

71. Betts, Calabria, and Pincock, “Why Refugees Are an Asset in the Fight Against Coronavirus.”

72. Betts, Calabria, and Pincock, “Why Refugees Are an Asset in the Fight Against Coronavirus.”

73. Betts, Calabria, and Pincock, “Why Refugees Are an Asset in the Fight Against Coronavirus.”

74. Saeed Anwar, Mohammad Nasrullah, and Mohammad Jakir Hosen, “COVID-19 and Bangladesh: Challenges and How to Address Them,” Front Public Health, Vol. 8, No. 154 (April 30, 2020).

75. Cristiano D’Orsi, “Governments Need to Do More for Refugees Affected by Coronavirus: Here’s How,” The Conversation, (April 15, 2020), retrieved April 28, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/governments-need-to-do-more-for-refugees-affected-by-coronavirus-heres-how-135861.

76. “Governments Need to Do More for Refugees Affected by Coronavirus.”

77. Alastair Ager, “Health and Forced Migration,” in Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Gil Loescher, Katy Long, and Nando Sigona (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 433-446; see especially p. 442.

78. Hans Henri P. Kluge, Zsuzsanna Jakab, Jozef Bartovic, Veronika d’Anna, and Santino Severoni, “Refugee and Migrant Health in the COVID-19 Response,” The Lancet, Vol. 395, No. 10232 (2020), pp. 1237-1239.

79. Abrahm Lustgarten, “Refugees from the Earth,” The New York Times Magazine, (July 26, 2020), pp. 7-23, 43; see especially p. 22.

80. Metin Çorabatire, “The Evolving Approach to Refugee Protection in Turkey: Assessing the Practical and Political Needs,” September 2016, Migration Policy Institute (MPI), retrieved November 10, 2020 from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/evolving-approach-refugee-protection-turkey-assessing-practical-and-political-needs.

81. Jeneen Interlandi, “We Must End the Cycle of Neglect, Panic, Repeat,” The New York Times, Sunday Review, (April 19, 2020), p. 7.

82. Isaac Chotiner, “The Danger of COVID-19 for Refugees,” The New Yorker, (April 10, 2020), retrieved April 28, 2020, from https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-danger-of-covid-19-for-refugees.

83. Justin Schon, “Protecting Refugees in the Middle East from Coronavirus: A Fight against Two Reinforcing Contagions,” The COVID-19 Pandemic in the Middle East and North Africa, Vol. 19, (2020).

84. Marie McAuliffe and Céline Bauloz, “The Coronavirus Pandemic Could Be Devastating for the World’s Migrants,” World Economic Forum, (April 6, 2020), retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/the-coronavirus-pandemic-could-be-devastating-for-the-worlds-refugees/.