This article examines the continuing importance of Turkish-Russian energy ties in the face of strains in relations between Ankara and Moscow over Syria. There is an assumption that the shooting down of a Russian jet over Turkish territory in November 2015 led to the collapse of Turkish Stream. However, this much-trumpeted project had already been suspended by Ankara, in part because of disagreements over gas pricing. Focusing on the significance of Russian gas exports and on Russian plans to construct Turkey’s first nuclear power plant, this article analyses developments before, during, and after the crisis in relations between Turkey and Russia over Syria. In this context, the Syrian crisis refers to the deterioration of relations between Turkey and Russia in the period from November 2015 to June 2016.

Close energy ties between Turkey and Russia were maintained after Russia invaded Georgia in 2008 and annexed Crimea in 2014. At first sight, the erstwhile successful compartmentalization of energy ties from other aspects of the Turkish-Russian relationship seemed to have collapsed over the fighter jet incident with the suspension of Turkish Stream. However, Turkish Stream had already run into serious difficulties by late July 2015 before the downing of the Russian jet. Meanwhile, Gazprom continued to deliver substantial volumes of gas to the Turkish market after November 2015, and preparatory work by the Russian state-owned Rosatom on Turkey’s first nuclear plant at Akkuyu, while slowed down, was not halted.

Turkey is Gazprom’s second largest export market after Germany. The suspension of gas deliveries to Turkey without proper legal reasoning would damage Russia’s reputation as an energy supplier

Turkey is greatly dependent on Russia for gas imports and this may give Moscow some leverage over Ankara’s policies. Nevertheless, there is a degree of mutual dependency in energy ties which could also be exploited by Turkish officials. In 2015 Turkey produced only 0.38 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas. Imports of gas from Russia amounted to 26.78 bcm out of total imports of 48.43 bcm.1 Gas will remain a crucial component in meeting Turkey’s energy needs for the foreseeable future. Ankara is seeking to diversify its gas imports by taking deliveries from alternative sources such as northern Iraq, Turkmenistan, and Israel, and by importing more liquefied natural gas (LNG), but this project will not be realized in the near term due to political and security concerns and a lack of infrastructure. Turkish policymakers are aiming to increase the use of renewables in the energy mix, use more locally produced coal, and develop nuclear power. However, Rosatom’s role in constructing Turkey’s first nuclear power plant, which is expected to produce 4,800 Megawatts of electricity, will only heighten Ankara’s energy dependence on Moscow.

It is important to note, on the other hand, that Turkey is Gazprom’s second largest export market after Germany. The suspension of gas deliveries to Turkey without proper legal reasoning would damage Russia’s reputation as an energy supplier and would likely result in Gazprom incurring heavy fines for breaking the terms of its long-term gas contracts. Russia is also eager to demonstrate that it is a serious international player in the construction of nuclear power units. However, Russia could still haggle over gas prices or take-or-pay obligations and temporarily reduce gas deliveries without violating the terms of its contracts. In effect, a range of options are available for Russia as a gas supplier to make life uncomfortable for Turkish consumers; this was evident in the months prior to the crisis in Syria when relations between Turkey and Russia deteriorated over the downing of the Russian jet.

Pre-Syrian Crisis I: Proposals for Turkish Stream

Institutionalized bilateral ties developed between Turkey and Russia after the establishment of a High-Level Cooperation Council in May 2010. In 2014, trade turnover between the two totalled over $31 billion and there were plans to surpass $100 billion by 2020.2Turkish companies were heavily involved in the construction and banking sectors in Russia. Almost four million Russian tourists visited Turkey annually. The close energy ties between the two countries reflected their warming political and economic relationship.

Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller speaks with Turkish Energy Minister Berat Albayrak as they arrive for a press conference on October 10, 2016 in İstanbul. | AFP PHOTO / OZAN KÖSE

Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller speaks with Turkish Energy Minister Berat Albayrak as they arrive for a press conference on October 10, 2016 in İstanbul. | AFP PHOTO / OZAN KÖSE

After extensive lobbying from Moscow, in late December 2011 Ankara eventually approved the construction of South Stream across Turkey’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Black Sea. This pipeline network envisioned the annual delivery of 63 bcm/y from Gazprom to Europe via four offshore lines which would connect the Russian mainland with Bulgaria. This project threatened to disrupt the plans of the European Union (EU) to reduce Europe’s energy dependency on Russia by promoting the Southern Gas Corridor, which aimed to carry non-Russian supplies of gas to markets in Europe via a new pipeline system crossing Turkey. In return for Ankara’s approval of South Stream, Moscow promised gas price discounts and flexibility in take-or-pay obligations; Russia also revised agreements so that Turkey could continue to receive a maximum of 14 bcm/y of Russian gas from the Western Line running through Ukraine and up to 16 bcm/y via Blue Stream running across the Black Sea until 2021 and 2025.3 But negotiations with the EU were halted after Russia annexed Crimea,4 and South Stream fell victim to objections from Brussels, which opposed the project on the grounds that it violated the provisions of the EU’s Third Energy Package with regard to Gazprom’s ownership of the planned pipeline network and control over gas transmission.

Although South Stream was encountering grave difficulties, it nevertheless came as a surprise when on a visit to Ankara on December 1, 2014, President Vladimir Putin announced that Turkish Stream would replace South Stream. According to the non-binding memorandum-of-understanding (MOU), 63 bcm of Russian gas would be transported to Europe and Turkey each year through four separate strands which would be laid across the Black Sea to connect Russia with Turkey instead of Bulgaria. One of these strands would supply gas to the Turkish market. There was talk at the time of Turkey also receiving an additional 3 bcm annually via Blue Stream and securing price reductions for future Russian gas deliveries.5 The planned Turkish Stream made sense for Moscow, which had already spent $4.7 billion on purchasing offshore pipes and building infrastructure on the Russian mainland for South Stream, that could instead be used for Turkish Stream.6 The new pipeline connection to Turkey could replace gas deliveries across the Western Line which Russia was considering closing after 2019 to avoid remaining dependent on troublesome Ukraine for gas transit. However, the provisions of the Third Energy Package still threatened plans for the delivery of Russian gas to EU member states via Turkish Stream. The project soon encountered technical problems, however, and became entangled with disagreements between Turkey and Russia over the prices for Russian gas currently being delivered to Turkish consumers.

A number of issues needed to be resolved before Turkish Stream could be implemented. An Inter-Governmental Agreement (IGA) had to be signed and ratified. The funding of the project needed to be agreed upon, the routes of the pipelines approved, and the responsibilities of Gazprom and Turkey’s state-owned pipeline company BOTAŞ hammered out. These issues became linked with the question of the discount for current gas deliveries from Gazprom, particularly to BOTAŞ.

Some provisional deals on Turkish Stream had been struck before talks were effectively halted. There were negotiations on scaling down the project to accommodate two instead of four strands on account of insufficient gas demand in Europe. Gas to Turkey would be fed along a new pipe carrying 15.75 bcm/y. This connection would be constructed first at an estimated cost of €4.3 billion.7 There were reports that Russia would pay for the costs of laying the underwater pipes while Gazprom and BOTAŞ would together develop the network across Turkish territory.8 But other issues could not be resolved. In June 2015, Russian authorities complained that Ankara had given permission for an engineering survey for the offshore network in Turkey’s EEZ in the Black Sea, but had not granted a license for construction.9 It was not clear who would own the gas delivered through the pipelines once it entered Turkish territory.10 And the funding of the project still needed to be addressed. With Gazprom also failing to agree on a price discount for current gas supplies to BOTAŞ after becoming involved in a dispute with private companies over gas deliveries to Turkey, Ankara declared the suspension of talks on Turkish Stream in late July 2015, before an IGA could be signed.11 Significantly, this was four months before the downing of the Russian jet. Work on the engineering survey for the offshore network was also halted.

Pre-Syrian Crisis II: Gas Pricing Problems

In theory, Russia could at any time threaten to raise gas prices to seek economic or political advantage in its relations with Turkey. Using the price of gas as leverage had become a traditional Russian foreign policy tool in the post-Soviet era. But, the case of Turkey was more complicated given the importance of the Turkish market, the role of private energy companies, and Moscow’s interest in cultivating closer ties with a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Gazprom did attempt to use the gas pricing issue to secure more preferential terms for the proposed Turkish Stream project. BOTAŞ, though, could take Gazprom to international arbitration over gas pricing. Complicating the matter, the non-binding MOU on Turkish Stream did not specify exactly what gas price discount would be offered to Turkey, and Gazprom delivered gas to private energy companies in Turkey at a price different than that set for BOTAŞ. Gazprom, itself, had stakes in several of these private energy firms. Disagreements over gas pricing came at a time when there was pressure on Gazprom in general to lower its prices to take into account the declining cost of oil.

It was the ongoing disagreements in gas pricing between Gazprom and BOTAŞ, rather than the Syrian crisis that resulted in the breakdown of talks on the proposed Turkish Stream

According to the terms of Turkey’s Natural Gas Market Law of 2001, BOTAŞ, which had enjoyed a monopoly on gas imports in the past, was obliged to reduce its market share in gas imports to 20 percent. By 2012, private energy firms had secured all of the 14 bcm/y originally contracted to BOTAŞ and delivered on the Western Line. These companies were able to negotiate lower gas prices with Gazprom because, unlike Turkey’s state-owned pipeline corporation, they did not benefit from generous subsidies from the Turkish government. Several of these firms had also entered into forms of partnership with Gazprom in the hope of obtaining preferential deals. For example, Bosphorus Gaz, which is contracted to import 2.5 bcm/y, is 71 percent owned by Gazprom Germania, a Berlin-based subsidiary of Gazprom. The Russian energy giant also holds a minority stake in Akfel Holding and has an option to buy 50 percent of Akfel Gaz. Three subsidiaries of Akfel Holding –Akfel Gaz, Avrasya Gaz and Enerco– together are contracted to import 5.25 bcm/y. However, in December 2016, Turkish authorities seized control of Akfel Holding out of suspicion that the company had close links with the exiled Fetullah Gülen, who is accused of orchestrating the attempted coup in Turkey in July 2016. As a consequence, Gazprom may lose its stake in Akfel Holding.12

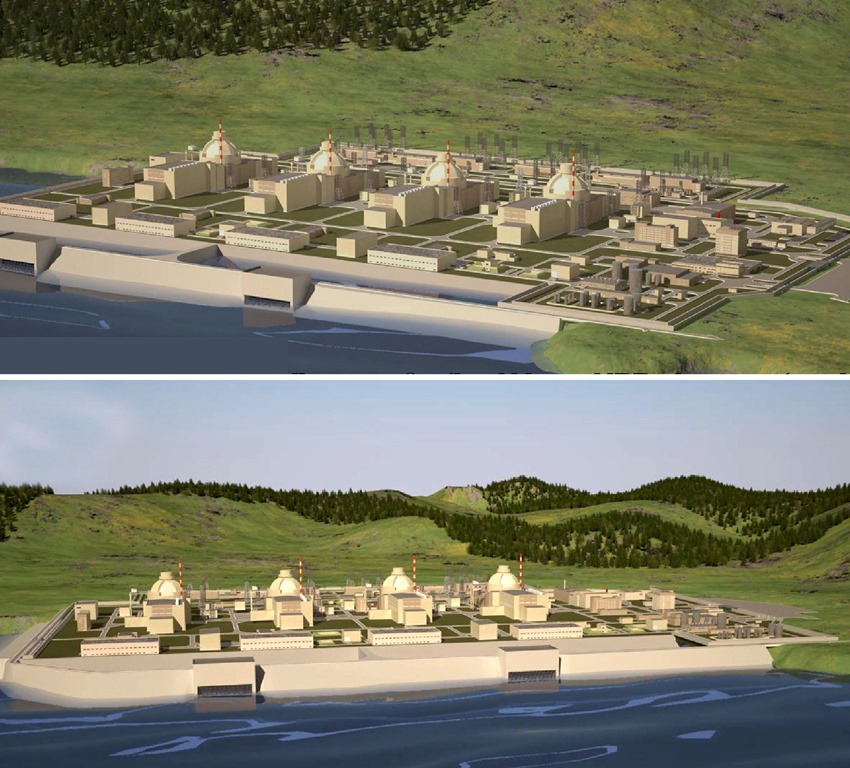

This is the first graphical illustration that depicts the proposed Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, which will be the first nuclear power plant for Turkey. The first unit is expected to be completed in 2022. | AA PHOTO

This is the first graphical illustration that depicts the proposed Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, which will be the first nuclear power plant for Turkey. The first unit is expected to be completed in 2022. | AA PHOTO

It seems that the gas price discount suggested in the non-binding MOU on Turkish Stream was exclusively aimed at BOTAŞ. The private energy companies had in January 2014 received a 10 percent price reduction from Gazprom for one year. To the surprise of these businesses, the discount was removed at the end of 2014 and a further 10 percent added so that they were faced with a bill of $374 for 1000 cm of gas, compared to a bill of $305-310 earlier in 2014.13 This hike in rates threatened to bankrupt the private companies given that they were forced to pay for Russian gas in dollars and sell it to consumers in Turkey in the depreciating Turkish lira (TRY).14 Eventually, in late April 2015 a deal was concluded between these companies and Gazprom to cover gas prices for 2015. As a part of the agreement, the price of gas for the first quarter of 2015 was lowered to $300 and further reduced to $260 for the second quarter.15

The friction between private energy companies and Gazprom over gas pricing at a time when the terms for the proposed Turkish Stream were being discussed served as a backdrop for the escalating tensions between Gazprom and BOTAŞ over pricing issues. The Turkish state-owned corporation had long been threatening to take Gazprom to international arbitration over pricing. BOTAŞ had been paying over $400 for 1000 cm of Russian gas since at least early 2014. Once plans for Turkish Stream were announced, the threat to go to international arbitration was dropped and in late February 2015 Turkish energy officials prematurely declared that BOTAŞ had secured a 10.25 percent price discount.16 Gazprom, however, refused to confirm the discount until progress was made in working out arrangements for Turkish Stream – on its terms. This kerfuffle culminated in the suspension of talks on Turkish Stream by Ankara in late July 2015. Gazprom then refused to increase gas deliveries along Blue Stream by 3 bcm/y, as previously promised (offering instead an extra 2 bcm/y in future via Turkish Stream).17 BOTAŞ responded by taking Gazprom to international arbitration.

In spite of the fighter jet incident, it is important to note that Gazprom continued to deliver gas to private companies and to BOTAŞ, and the pricing dispute with private firms was able to be settled with the April 2016 agreement

Therefore, it was the ongoing disagreements in gas pricing between Gazprom and BOTAŞ, rather than the Syrian crisis that resulted in the breakdown of talks on the proposed Turkish Stream. Ironically, however, Turkish Stream could only be rescued by means of the subsequent resolution of the Syrian crisis by Ankara and Moscow.

The Syrian Crisis

On November 24, 2015, Turkish armed forces shot down a Russian Su-24 over what officials in Ankara claimed was Turkish airspace. A furious President Putin referred to this action as a “stab in the back,” and warned that there would be “serious consequences” for Russian-Turkish relations.18 Moscow immediately accused Ankara of indirectly supporting the so-called Islamic State (IS or ISIS) by turning a blind eye to oil smuggling across the Turkish-Syrian border which supposedly helped finance ISIS militants.19 In turn, Turkish officials condemned Moscow’s close ties with the Syrian Kurds. In Ankara’s opinion, the Syrian PYD (Democratic Union Party) was no different than the PKK (the Kurdistan Workers’ Party) which was recognized as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the EU and the U.S., but not by Moscow.

Contrary to a general assumption, the resurrection of Turkish Stream was thus not the primary motive for the Turkish moves to seek reconciliation

Russia responded to the downing of its jet by banning direct flights to Antalya. This had a devastating impact on the Turkish tourist industry. The visa-free regime with Turkey was unilaterally suspended by Russia and sanctions were imposed on a range of Turkish food exports. Turkish companies could not embark on new construction projects in Russia unless they were given special exemption. The impact of these measures on trade turnover was drastic. In the first half of 2016, trade between Turkey and Russia only totalled $8.5 billion. Turkish exports to Russia in this period amounted to $737 million – the worst figures since 2004.20

Under these circumstances, there was no prospect of reviving Turkish Stream nor resolving the gas price dispute between Gazprom and BOTAŞ. In spite of close ties with Gazprom in many cases, the gas pricing dispute between private energy companies working in Turkey and Gazprom was also resumed. According to Enerco, in February 2016 Gazprom reduced deliveries to private importers after they refused to pay a higher price for Russian gas.21 It appears that the price had risen by 10.25 percent in January 2016. An agreement was concluded in April 2016 in which an undisclosed discount was arranged and full gas deliveries resumed, although it seems that the private firms were still paying more for Russian gas than they had been in 2015.22

In spite of the fighter jet incident, it is important to note that Gazprom continued to deliver gas to private companies and to BOTAŞ, and the pricing dispute with private firms was able to be settled with the April 2016 agreement. Russia also committed itself to continue preparatory work on the nuclear power plant at Akkuyu. In December 2015, President Putin noted that the deal on the power plant was “strictly commercial” and would not be affected by the political crisis between Russia and Turkey. Akkuyu was a flagship project for Moscow and $3.5 billion had already been invested.23 Ankara delayed work on the project but even at the height of the Syrian crisis progress was made with regard to the possible selling of a 49 percent stake in the future power plant to a Turkish consortium led by Cengiz Construction.24 Given the economic problems in Russia in the face of Western sanctions after the annexation of Crimea, Moscow was keen to sell a substantial stake to help finance the nuclear power plant.

Post-Syrian Crisis: Reconciliation

On June 27, 2016, President Erdoğan sent a letter to his Russian counterpart expressing his regret for the downing of the Russian jet.25 Turkey had suffered economically as a result of the wide-ranging sanctions imposed by Moscow. It was also in Ankara’s interests to improve ties to ensure that the Kremlin would not oppose any Turkish military intervention in Syria to prevent the Syrian Kurds from establishing a corridor of territory under the control of the PYD along the Turkish-Syrian border. Contrary to a general assumption, the resurrection of Turkish Stream was thus not the primary motive for the Turkish moves to seek reconciliation.

The coup attempt in Turkey in July 2016, which prompted Putin’s immediate message of support for President Erdoğan, helped to re-energize ties and the two leaders met in St. Petersburg the following month. Direct flights from Russia to Antalya resumed and sanctions started to be lifted on some Turkish agricultural products. Having presumably informed the Russians beforehand of their intentions, Turkish Armed Forces entered Syria on August 24, 2016 to attack ISIS positions and prevent the possible establishment of a PYD-controlled corridor. At the time of this writing, the situation on the ground in Syria remains highly fluid in spite of a Turkish-Russian brokered ceasefire, and ties between Ankara and Moscow could again fracture over issues such as the fate of the Assad regime and the future of the Syrian Kurds.

In the sphere of energy, since the reconciliation further progress has been made in preparatory work for the nuclear power plant at Akkuyu. In August 2016 Ankara accorded the project “strategic investment” status. This entitled the project to secure financial support and incentives potentially worth billions of dollars. For example, Akkuyu will be exempt from an 18 percent value-added tax and will benefit from a 90 percent reduction in corporate taxes.26 In November 2016 it was reported that Rosatom was engaged in serious negotiations with the Cengiz-Kolin-Kalyon (CKK) Group to sell a 49 percent stake in the project.27 The realization of the project would be prestigious for Turkey, marking its entry into the select club of states producing nuclear power. Plans to construct two more nuclear power plants with partners from other states would help make Turkey less dependent on Russia for energy.

Turkish Stream was also resurrected. At the August 9, 2016 meeting in St. Petersburg, President Erdoğan declared that the pipeline project would be implemented and that a decision had been made to set up a working group and prepare a road map.28Nevertheless, the issues and problems that had plagued the project before the Syrian crisis still needed to be addressed.

Since late summer 2016, progress on the development of Turkish Stream has been surprisingly rapid. In September 2016 Gazprom obtained survey permits for two offshore strings in Turkey’s EEZ and finally secured a license to construct the offshore section.29An IGA for the project was signed by the two energy ministers at the World Energy Congress in İstanbul on October 10, 2016. This provided the necessary legal framework to construct two offshore and onshore strings, each with a capacity of 15.75 bcm/y, to carry gas to the Turkish market and to Turkey’s border.30 Russia’s Minister of Energy, Alexander Novak, noted that Russia would construct and own the maritime stretch of both pipelines. The land part of the network supplying gas to Turkey would be owned by a Turkish company (presumably BOTAŞ) and a joint venture would be created by the two states (presumably Gazprom and BOTAŞ) which would assume ownership of the transit pipeline. Novak added that talks between Gazprom and BOTAŞ had resumed over a possible gas price discount.31 The IGA for Turkish Stream was ratified by Ankara in December 2016. On December 6, 2016, the head of Gazprom, Alexey Miller, stated that both underwater branches would be on stream by the end of 2019, and that Gazprom was giving priority to the development of a transit route which would run across Turkish territory to the border with Greece.32 Two days later it was announced that Gazprom had signed a contract with Switzerland’s Allseas Group to construct the first offshore line with an option for laying pipes for a second strand.33

Prospects

There has been much hype that the reconciliation between Turkey and Russia, coupled with Ankara’s problems with Brussels over the EU accession talks and with Washington over the fate of Fetullah Gülen, would lead to a fundamental re-orientation of Turkish foreign policy. It was seen as striking that in November 2016 Turkey was unanimously elected to chair the Energy Club of the Shanghai Cooperation Club (SCO). This had immediately followed observations made by President Erdoğan that Turkey should seriously again consider applying for full membership in the regional body led by China and Russia.34 However, Turkey is unlikely to turn its back completely on Europe and abandon the U.S. and NATO in the foreseeable future given their close economic, political and security links. At the time of writing, ties between Turkey and Russia are continuing to be re-calibrated. Relations could again cool over Syria, although in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of the Russian ambassador in Ankara in December 2016, Turkish officials were careful not to disturb the rapprochement with Moscow. Nevertheless, the Kremlin was in no hurry to restore the visa-free regime with Turkey and sanctions remain on some Turkish food exports.

Turkey is unlikely to turn its back completely on Europe and abandon the U.S. and NATO in the foreseeable future given their close economic, political and security links

In the field of energy, given the importance of the relationship for both Turkey and Russia, work on the Akkuyu nuclear power plant is expected to continue and the contract to supply Russian gas to Turkey via Blue Stream will probably be renewed or extended beyond 2025. However, gas pricing issues may remain problematic between Gazprom and BOTAŞ, as well as private energy companies operating in Turkey. With that said, these issues in themselves will not seriously damage energy ties and are less likely now to create problems for Turkish Stream given recent developments over the pipeline project.

The important energy relationship between Turkey and Russia stands poised to continue for the foreseeable future in spite of any possible future downturns in political ties

Turkish Stream is back on track and, indeed, progress on the project has rapidly accelerated in the wake of the reconciliation between Ankara and Moscow. In spite of the signing of the IGA, though, several issues await resolution. It is not clear how the project will be funded given the financial problems in both Russia and Turkey. An explanatory document attached to the draft bill for the ratification of the IGA stated that $7.3 billion in investments was required for a two-pipeline network.35 There are also serious questions over whether a second transit line to Greece will actually be built. President Putin insists that Brussels should first provide guarantees that they will not attempt to block that part of the project involving EU member states.36 It is possible that Russian gas from Turkish Stream could hook up in future with the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to deliver gas to southern Italy via Albania or by means of the planned extension of the Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy, but Moscow would first want to have definite backing from Brussels for either of these alternatives.

Energy policymakers in Ankara have repeatedly stressed that one of their aims is to promote Turkey as an energy hub and that cooperation with Russia will not jeopardize this goal. Turkish Stream will most probably not threaten Turkey’s prospects of becoming an energy hub given that other gas pipeline projects are going ahead. Work is accelerating on constructing the EU-backed Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) to carry gas initially from Azerbaijan to TAP, and then to Europe via Turkey. Gas from other suppliers such as Turkmenistan or northern Iraq could later connect with TANAP. Moscow would prefer not to face such competition, but Brussels is keen for EU member states to be less dependent on Russian gas imports. Turkey has the potential to increase its importance as an energy transit state, although more market reforms are needed to make Turkey an effective energy hub, and to attain its aspiration of becoming the region’s “most important gas distribution point.”37

Work will most probably proceed on the first offshore section of Turkish Stream to provide 15.75 bcm/y of gas to consumers in Turkey. This will not deepen Turkey’s energy dependence on Russian as this volume will likely replace gas currently delivered to Turkey along the Western Line via Ukraine. In this case, though, Gazprom would need to make arrangements with those private companies operating in Turkey which have been purchasing gas transported along the Western Line – some of these contracts extend beyond 2021. A second offshore and onshore section may not be built, given Brussels’ lack of enthusiasm for the project, but a further scaled-down Turkish Stream would be cheaper than the originally planned larger project with four separate strands and perhaps therefore more feasible.

The important energy relationship between Turkey and Russia stands poised to continue for the foreseeable future in spite of any possible future downturns in political ties. Given the interdependence of this relationship, it is able to weather the most serious of crises, as seen in the case of Syria. There may be future disputes over gas pricing, the funding of energy projects, and other technical issues, but Ankara and Moscow appear destined to remain key energy partners.

Endnotes

- “Doğal Gaz Piyasası 2015 Yılı Sektör Raporu,” T.C. Enerji Piyasası Düzenleme Kurumu, pp. 2, 8, retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.epdk.org.tr/TR/

Dokumanlar/Dogalgaz/ YayinlarRaporlar/Yillik. - Mehmet Çetingüleç, “Can Turkey-Russia Trade

Reach $100 Billion Target?,” Al-Monitor, (August

22, 2016), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/

2016/08/turkey-russia-trade-reach-100-billion-target.html. - Gareth Winrow, Realization of Turkey’s Energy Aspirations: Pipe Dreams or Real Projects, (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institute, Turkey Project Policy Paper 4, April 2014), pp. 6-7. The 1986 deal to deliver 6 bcm/y to Turkey along the Western Line, due to expire in 2011, was extended to 2021. The 1998 deal to transport 8 bcm/y to Turkey along the same line to 2021 was extended to 2025. The 1997 agreement to carry 16 bcm/y to Turkey via Blue Stream to 2022 was also extended to 2025.

- “South Stream Victim of Crimea Annexation,” EurActiv, (March 23, 2014), retrieved December 21, 2016, from https://www.euractiv.com/

section/energy/news/south- stream-victim-of-crimea- annexation/. - Darya Korsunskaya, “Putin Drops South Stream Gas Pipeline to EU, Courts Turkey,” Reuters, (December 1, 2014), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.reuters.com/

article/us-russia-gas-gazprom- pipeline-idUSKCN0JF30A20141201 . - Jonathan Stern, Simon Pirani and Katya Yafimava, “Does the Cancellation of South Stream Signal a Fundamental Reorientation of Russian Gas Export Policy?,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (January 2015), pp. 5-6, retrieved December 21, 2016, from https://www.oxfordenergy.org/

wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2015/ 01/Does-cancellation-of-South- Stream-signal-a-fundamental- reorientation-of-Russian-gas- export-

policy-GPC-5.pdf. - “Cost of Turkish Stream Estimated at 11.4 Billion Euros,” Hürriyet Daily News, (August 11, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.

com/cost-of-turkish-stream- estimated-at-114-billion- euros.aspx?pageID=

238&nID=86760&NewsCatID=348. The total costs

here referred to the expenditure required to build

four pipelines. - “Russia and Turkey Agree on a New Gas Route,” RT, (January 27, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from https://www.rt.com/business/

226747-turkey-stream-gas- route/. - Orhan Coskun, “Turkey Could Take Russia to Arbitration over Gas Price Next Week,” Reuters, (June 26, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://af.reuters.com/article/

energyOilNews/ idAFL8N0ZC29P20150626. - Jack Farchy and Mehal Srivastava, “Turkey Initiates Legal Action Against Russia’s Gazprom,” Financial Times, (October 27, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from https://www.ft.com/content/

11665996-7cc6-11e5-a1fe- 567b37f80b64. - “Turkish Stream Pipeline Talks between Moscow and Ankara Suspended – Turkish Officials,” Hürriyet Daily News, (July 30, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.

com/turkish-stream-pipeline- talks-between-moscow-and- ankara-suspended-turkish- officials.aspx?pageID=238&nID= 86162&NewsCatID=348. - “Gazprom May Lose Shares in Turkey’s Largest Private Importer of Russian Gas,” Sputnik International, (December 20, 2016), retrieved December 21, 2016, from https://sputniknews.com/

business/201612201048776929- gazprom-akfel-shares/. The other private companies in Turkey importing Russian gas are Kibar Enerji and Batı Hattı Doğalgaz Ticaret, each with contracts to import 1 bcm/y, and Shell with a contract to import 0.25 bcm/y. - “Gazprom Price Hikes to ‘Pressure’ Turkey: ex-BOTAŞ Head,” World Bulletin, (February 19, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.worldbulletin.net/

gas/155349/gazprom-price- hikes-to-pressure-turkey-ex- botas-head. - Aura Sabadus, “Gazprom, Turkish Importers Agree on Discount – Sources,” ICIS, (April 28, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.icis.com/resources/

news/2015/04/28/9880344/ gazprom-turkish-importers- agree-on-discount-

sources/. - “Russia’s Gazprom Reduces Gas Export to Turkey’s Private Sector Companies by 10 Percent,” Daily Sabah, (February 25, 2016), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.dailysabah.com/

energy/2016/02/25/russias- gazprom-reduces-gas-export-to- turkeys-private-sector- companies-by-10-percent. - Emre Gürkan Abay, “Major Obstacles Stand in Way of ‘Turkish Stream,’” Anadolu Agency Energy News Terminal, (July 23, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.aaenergyterminal.

com/newsMain.php?newsid= 5913464. - Şeyma Eraz, “Russian Energy Giant Gazprom Refuses Turkey’s Demand for Additional Natural Gas,” Daily Sabah, (October 9, 2015), retrieved December 21, 2016, from http://www.dailysabah.com/

energy/2015/10/09/russian- energy-giant-gazprom-refuses- turkeys-demand-for-additional- natural-gas. - Don Melvin, Michael Martinez and Zeynep Bilginsoy, “Putin Calls Jet’s Downing ‘Stab in the Back’: Turkey says Warning Ignored,” CNN, (November 25, 2015), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://edition.cnn.com/2015/

11/24/middleeast/warplane- crashes-near-syria-turkey- border/. - “Ankara’s Oil Business with ISIS,’ RT, (November 25, 2015), retrieved December 22, 2016, from https://www.rt.com/business/

323391-isis-oil-business- turkey-russia/. - Çetingüleç, “Can Turkey-Russia Trade Reach $100 Billion Target?.” In 2015, total trade turnover between Turkey and Russia amounted to approximately $24 billion, of which $3.6 billion were Turkish exports to Russia. Turkish Statistical Institute, retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/

PreTablo.do?alt_id=1046. - Aura Sabadus, “Gazprom ‘Unilaterally’ Hikes Price to Turkey – Importer,” ICIS, (March 1, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.icis.com/resources/

news/2016/03/01/9974792/ gazprom-unilaterally-hikes- price-to-turkey-importer/. - “Gazprom to Restart Full Gas Exports to Turkish Gas Firms,” Anadolu Agency, (April 13, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://aa.com.tr/en/turkey/

gazprom-to-restart-full-gas- exports-to-turkish-gas-firms/ 554265. - “Putin Says Construction of Nuclear Plant ‘Strictly Commercial’,” Kallanish Energy, (December 21, 2015), retrieved December 22, 2016,

from https://www.kallanishenergy.com/2015/12/

21/5607/. - “Turkey’s Cengiz in Talks with Russia’s Rosatom to Buy Nuclear Plant Stake – Source,” Reuters, (April 27, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://uk.reuters.com/article/

turkey-russia-

nuclearpower-idUKL5N17U2AS. - Jack Stubbs and Dmitry Solovyov, “Kremlin Says Turkey Apologized for Shooting Down Russian Jet,” Reuters, (June 27, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.reuters.com/

article/us-russia-turkey-jet- idUSKCN0ZD1PR. - Zülfıkar Doğan, “Putin Gets Big Kiss-and-Make-up Gift from Erdoğan,” Al-Monitor, (August 16, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.al-monitor.com/

pulse/originals/2016/08/ turkey-russia-nuclear-plant- special-status.html. - “Rosatom Holds Talks with Turkish CKK Group for Akkuyu Partnership,” Daily Sabah, (November 15, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.dailysabah.com/

energy/2016/11/15/rosatom- holds-talks-with-turkish-ckk- group-for-akkuyu-partnership. - John Roberts, “Putin to Set Turkish Stream Terms: Analysis,” Natural Gas World, (August 10, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.naturalgasworld.

com/turkish-stream-to-follow- putins-terms-30990. - “TurkStream,” Gazprom Export, retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.gazpromexport.ru/

en/projects/. - For the text of the IGA see, “Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Turkey and the Government of the Russian Federation Concerning the TurkStream Gas Pipeline Project,” Resmi Gazete, (December 24, 2016), retrieved December 24, 2016, from http://resmigazete.gov.tr/

main.aspx?home=http://www. resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/ 2016/12/20161224.htm. - “Turkish Stream Gas Pipeline: Moscow and Ankara Sign Agreement in Istanbul,” RT, (October 10, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from https://www.rt.com/business/

362279-gazprom-turkish-stream- pipeline/. - “Gazprom CEO Says Construction of Turkish Stream’s Offshore Segment to Start in 2017,” Tass, (December 6, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://tass.com/economy/917186

. - “Gazprom Signs Contract for Construction of Turkish Stream’s First Line with Allseas,” Tass, (December 8, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://tass.com/economy/917853

. - “Turkey to Chair 2017 Energy Club of Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Daily Sabah, (November 23, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.dailysabah.com/

energy/

2016/11/23/turkey-to-chair-2017-energy-club-

of-shanghai-cooperation-organization. - “Implementation of Turkish Stream Project Requires $7.3 Bln Investment,” Sputnik International, (December 20, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from https://sputniknews.com/

business/201612201048802260- russia-turkey-gas-stream- project/. - “Vladimir Putin’s Annual News Conference,” En.Kremlin.Ru, (December 17, 2015)), retrieved December 22, 2016, from en.kremlin.ru/events/

president/news/50971. - Daniela Bochkarev and Volkan Özdemir, “The EU-Russia-Turkey Energy Triangle,” Elektormagazine, (June 22, 2016), retrieved December 22, 2016, from https://www.elektormagazine.

com/news/the-eu-russia-turkey- energy-triangle.